The National Socialist White

People’s Party (1967-1982)

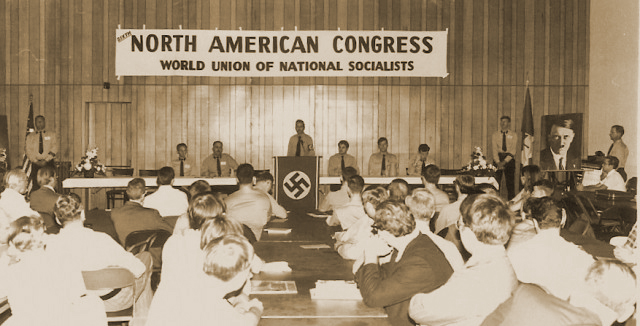

Second day of the sixth congress of the NSWPP and the

World Union of National Socialists, Milwaukee, 1975.

A telephone call came into the national headquarters of the National Socialist White People’s Party about half-past noon on August 25, 1967. National Secretary Matt Koehl took the call. It was a person claiming to be a reporter. He wanted the party’s comment on the assassination of NSWPP founder George Lincoln Rockwell. Koehl hung up without replying; he assumed it was one of the dozens of prank calls that the headquarters received each day. He knew that Rockwell was alive, as he had spoken to him in person some 40 minutes earlier; now he was impatiently waiting for the Commander’s return from the local laundromat so that he could use the vehicle that Rockwell had taken for a party activity.

Moments later the phone rang again, and once more it was someone else who said he was a reporter, asking for a comment on Rockwell’s death. Again Koehl hung up. Within seconds there was a third call – but this time, before Koehl could slam down the receiver, he heard the caller say the word ‘laundromat’.

‘It was as if an icy-cold hand gripped my hear’, he later said.

Koehl quickly dispatched a trooper on foot to run down to the laundromat, about a quarter-mile away, to see if Commander Rockwell was all right. Shortly afterwards, the trooper returned. He was out of breath and drenched in sweat from running in the 90-degree summer heat. Commander Rockwell had been shot, he reported. His body was laying on the parking lot pavement, surrounded by a crowd of curious onlookers who were being held back by the police.

‘I instantly knew two things’, Koehl later recalled. ‘First, that he had been killed to stop his life’s work, and second, that I would not let that happen’.

The era of George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party was over, and the era of Matt Koehl and the National Socialist White People’s Party had begun.

Transition and survival

Technically, the era of the American Nazi Party had ended some nine months earlier, when Rockwell had renamed the group as the NSWPP. The name change was only one component of a sweeping program he had announced to transform the noisy band of political dissidents he had gathered around himself into a serious political movement for angry American Whites. The transition of the party from a group specializing in street theatre to one engaging in legitimate grass-roots activism had only just begun when Rockwell was killed. It fell on Koehl and his co-workers to carry it out as best they could.

But Koehl had a more-pressing priority before him: the very survival of the party itself.

In the tumultuous days and weeks following the assassination, the party initially rallied behind Koehl as its new leader. At first, Koehl refused to assume the title of ‘commander’, although as Rockwell’s designated successor he was entitled to do so.

Instead, he called himself ‘National Leader’. He imposed a two-year probationary period on himself. At the end of that time, he said, he would consult the party’s membership, and if they were satisfied with the job he was doing, then he would continue as ‘commander’. Otherwise, he would step aside.

But the initial surge of party solidarity that followed Rockwell’s death soon evaporated, and fissures in its organizational structure emerged. Part of the problem was that Koehl, then 32 years old, had a very different personality from Rockwell, who was 49 at the time of his death. The 6’4’ Rockwell was gregarious and dramatic and dominated the gathering whenever he entered a room. All eyes were on him. The younger, smaller Koehl, on the other hand, was quiet and introverted. Some in the party mistook his low-key personality as a sign of weakness. They thought that it would be easy for them to control him. All bookishness aside, however, Koehl possessed an iron will and a clear vision of what needed to be done to build National Socialism in America. Soon, his critics were gone, either having been expelled for insubordination or having voluntarily resigned. Some of them convinced that they could do a better job than Koehl, set up their mini versions of the ‘American Nazi Party’. We will discuss some of these splinter groups in the next instalment of this series.

So, despite the unprecedented avalanche of free publicity that followed the assassination, the NSWPP soon found itself short of manpower and money. The party headquarters in Chicago and Los Angeles were shuttered, and key personnel were transferred to Arlington. The NSWPP’s printing plant in Spotsylvania, Virginia, was also closed, and the group lost its mail-order operation in Dallas, Texas. By the end of 1967, it had been evicted from its famous ‘Hatemonger Hill’ headquarters in Arlington. Enemies of the party gleefully predicted that its end was at hand. The New York Times published a lengthy obituary for the NSWPP, entitled ‘Rockwell’s Nazis Lost without Him’.

But Koehl refused to let the party die. By the middle of 1968, a small brick-and-stone building had been purchased to serve as the new headquarters. An impressive, hardcover edition of Rockwell’s posthumous book, White Power, was published. The new party tabloid newspaper, also called White Power, began to appear although on an irregular basis at first. Soon, the party opened a second facility in Arlington, the ‘George Lincoln Rockwell Bookstore’.

The new momentum was partly due to two officers whom Koehl had recruited: Dr William L. Pierce and Robert Lloyd. Pierce had been a behind-the-scenes consultant to Rockwell during the mid and late 1960s; now in the hour of need, he stepped forward to play a more prominent role. He became the party’s National Secretary and public outreach officer. Pierce brought a new level of professionalism and intelligence to the party’s publications. He also pioneered new outreach forms, such as the ‘White Power Message’. This was a three-minute telephone recording on various topical issues that was changed periodically. Thousands of listeners called the service weekly, including many who were otherwise unwilling to contact the party.

Lloyd had been a captain in Rockwell’s Stormtroops but had drifted away in the year before the assassination. Now, he returned as the group’s National Organizer, charged with recruitment, public activities and with forming new party units throughout the country.

On Labor Day weekend, 1969, some two years after Rockwell’s death, the party held its first-ever national congress, attended by over 120 delegates. The congress included a closed session for full members and officers only. At this time, Koehl’s leadership was unanimously reconfirmed, and he officially became the party ‘commander’.

Yet all was not well within the group. In June 1970, Pierce made a bid to oust Koehl as the party’s supreme leader. Instead, he demanded that the party be run by a committee chaired by himself. Under this scheme, Koehl would stay on as the Movement’s figurehead but would have no power.

Once again, Koehl’s opponents underestimated him. By August 1970, Pierce was gone, as was Robert Lloyd, who had supported Pierce’s power-play. Pierce later admitted that his effort to supplant Koehl had been an error. To use a contemporary term, both men were ‘alpha males’. Each had his vision on where to lead the Movement, and neither was inclined to take orders from the other. Pierce went on to form his group, the National Alliance, which will be discussed in the next instalment of this series.

Happily, despite the ill feelings that accompanied the split, by the end of the decade, Koehl and Pierce were again on speaking terms. As the saying goes, they ‘agreed to disagree’ on the best way forward for our Race. Still, Pierce’s departure was a major setback for the Rockwell movement.

But the ‘Pierce mutiny’ (as it was called within the NSWPP), was only the first in a decade-long series of similar episodes. Time and again, Koehl would build the NSWPP up to a certain level, only to have all of the progress undone by internal difficulties.

Koehl as a leader

Both inside and outside the party, people measured Koehl as a leader against their memories of Rockwell. And at first, Koehl made the same comparison himself. By such standards, he fell far short. For one thing, he lacked Rockwell’s charisma and exuberance. At the beginning of his tenure, Koehl’s speaking ability was poor. He did not have Rockwell’s ability to improvise before an audience. Instead, Koehl would read his speeches from a typewritten text, only rarely looking up. Over time, he developed into an impressive and dynamic speaker – but that is not how he started.

His effort to be an imitation of Lincoln Rockwell was a failure. He later told me that just as each of us has a unique personality, so each leader must find his unique style of leadership. It was a mistake, he said, for him to try and copy Rockwell’s style, as his personality and talents were far different. But in time he found his leadership style. It included careful forethought, methodical preparation and scrupulous attention to detail. He used the organizational sections of Mein Kampf as an inflexible guide to party-building and operations. But like Rockwell, he also led from the front. He was injured and arrested numerous times on party activities, although as commander he could have held himself aloof from danger. Above all, he never asked his men for something that he was not willing to do.

A famous example of this took place in Miami, Florida, on August 20, 1972, when Koehl spearheaded 23 Stormtroops in civilian clothes in a raid on a Marxist encampment in Flamingo Park. Koehl led the National Socialists in capturing the speakers’ platform, which the ST men then defended for two hours against repeated assaults by hundreds of communists before finally being overrun and forced from the park. The event, which took place near the site of the Republican presidential convention, garnered the NSWPP worldwide news coverage.

Gradually, a corps of Koehl loyalists emerged, both in Arlington and local units scattered across the country. These were men and women who understood and appreciated his disciplined leadership style in itself, as different as it was from Rockwell’s freewheeling, impromptu leadership of the previous decade.

Rockwell’s strategy had been based on what we may call ‘punctuated equilibrium’: long periods of stasis interspersed with dramatic breakthroughs. Koehl, on the other hand, worked on the theory of slow growth and consolidation:small, incremental gains that added up over a long period.

At first, Koehl, adhered to Rockwell’s Four-Phase program (discussed previously) as closely as he could. But over time, he began to diverge from it, only a little bit at first, and then more and more as time went on. Instead, he made practical progress in building the party whenever he could, with no real thought to a long-term NS ‘seizure of power’.

The NSWPP in the 1970s

Under Koehl’s leadership, the NSWPP grew into an impressive, nationwide organization with headquarters and bookstores in major US cities, such as Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles and elsewhere. For a while, it had a 15-minute program of news commentary on AM radio, entitled The Future Calls. The White Power newspaper was published monthly, and an internal newsletter, the NS Bulletin was issued twice a month. In addition, the party published a theoretical journal on behalf of the World Union of National Socialists. But it was not its publications for which the Party was best known, but rather for its relentless, high-energy, high-profile public activism.

Full membership in the party was restricted to those comrades who had proven their full commitment to the cause. Those who applied for membership were vetted. After a probationary period lasting from one to two years, they had to pass an interview before a panel of party officers. As a minimum, members were expected to tithe ten per cent of their net income to the party, to purchase and distribute fifty copies of White Power each month, and attend all private and public party activities in their area.

In addition to the party itself, there were three auxiliary formations. The best known was the paramilitary Stormtroops (ST). There was also a women’s auxiliary (the National Socialist Women’s Organization or NSWO) and a youth group (the National Socialist Youth Movement or NSYM). The NSW did not take part in public demonstrations but served behind the scenes in a support capacity. The NSYM provided National Socialist training for young men 14 through 17, who then normally went on to join the ST.

The party reached its numerical peak during the mid-1970s. At that point, it had approximately 600 Official Supporters and another hundred full and probationary members. The ST numbered approximately 200 men nationwide. The NSWPP routinely conducted uniform demonstrations with fifty to a hundred participants and on a few occasions, the number of troopers was over a hundred. In 1973, at the fifth NSWPP national congress in Cleveland, Koehl led 126 uniformed Stormtroops in a public march down Euclid Avenue. The police were present but kept their distance – as did a dispirited gaggle of ‘anti-Nazi’ protestors. In contrast, Rockwell had never been able to field more than two-dozen or so troopers on any single occasion.

(Commander Matt Koehl leading a march at the Fifth NSWPP Congress, September 1, 1973.) Some NSWPP activities may seem startling by the standards of 2018. In 1976 and 1977, a contingent of uniformed Stormtroops, led by three drummers and a flag bearer, marched in the annual Arlington, Virginia, Fourth of July parade, along with the high school band, the VFW, the Rotary and other non-controversial participants. As I can personally attest, the National Socialists received both cheers and catcalls from onlookers along the parade route.

(Commander Matt Koehl leading a march at the Fifth NSWPP Congress, September 1, 1973.) Some NSWPP activities may seem startling by the standards of 2018. In 1976 and 1977, a contingent of uniformed Stormtroops, led by three drummers and a flag bearer, marched in the annual Arlington, Virginia, Fourth of July parade, along with the high school band, the VFW, the Rotary and other non-controversial participants. As I can personally attest, the National Socialists received both cheers and catcalls from onlookers along the parade route.

Other activities were less peaceful and ended in violence when party personnel were attacked. One such dramatic episode took place in December 1977, when a half-dozen ST men repelled an attack on the Arlington headquarters by 40 communists armed with rocks and clubs. One ST man and four Reds were hospitalized from injuries they received in the brawl.

Beginning in 1975, the NSWPP began running candidates for local office as open National Socialists in areas where it had a strong organizational presence. Typically, the candidates would run for the school board or mayor. Party candidates never won less than 5.5 per cent of the vote, and on a few occasions they received nearly 20 per cent. In some instances, the percentage of the White vote was upwards of 30 per cent.

The strongest results for the party came in the February 1977 primary race for the Milwaukee school board. The NSWPP fielded two candidates, Sandra Osvatic and Sandra Enders. Both were members of the NSWO and had husbands in the ST. Both women received about twenty per cent of the vote cast; Comrade Enders, with 7,710 votes, came within 300 votes of winning her seat. In contrast, Lincoln Rockwell had garnered only 5,730 votes – barely one per cent – when he ran for governor of Virginia in 1965.

These election results amazed political observers. If a minimum of five per cent of the voters nationwide were prepared to vote for the NSWPP, this indicated that the party had a potential base of support in White America of 10 million people.

Theoretical development

Rockwell had deliberately kept the program and outreach of the party very simple. For him, just displaying the Swastika and images of Adolf Hitler was sufficient to establish the Movement as National Socialist. To the degree that there was an ideology, it was a mélange of basic NS racialism, common sense, and traditional American right-wing policies. Rockwell himself had a penetrating and profound understanding of Hitlerian National Socialism, but he thought that an appeal based solely on the ideas embodied in Mein Kampf and practised in the Third Reich would be impossible to sell to American Whites. Consequently, he put forth a simplified version of National Socialism that he hoped would resonate among his fellow countrymen.

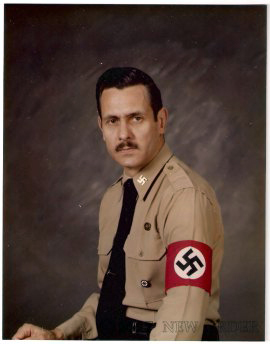

(Matt Koehl in 1978.) Koehl’s outreach, on the other hand, hewed more strictly to the German model of National Socialism. Unlike Rockwell, Koehl did not have a personal background in the American right, and he had no sympathy for its fixations. He strongly supported the socialist elements in National Socialism. Unlike Rockwell, he did not champion ‘Western Christian civilization’. Rather, his spirituality had a more heathen cast to it. Above all, Koehl stressed the centrality of Adolf Hitler to the National Socialist cause.

(Matt Koehl in 1978.) Koehl’s outreach, on the other hand, hewed more strictly to the German model of National Socialism. Unlike Rockwell, Koehl did not have a personal background in the American right, and he had no sympathy for its fixations. He strongly supported the socialist elements in National Socialism. Unlike Rockwell, he did not champion ‘Western Christian civilization’. Rather, his spirituality had a more heathen cast to it. Above all, Koehl stressed the centrality of Adolf Hitler to the National Socialist cause.

In 1980, thirteen years after he had assumed command of the party, a new, formal NSWPP program was issued. It was written jointly by Koehl and his chief of staff, Martin Kerr.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: I was unaware, until today, that Martin Kerr, the author of this series, held this position in the noblest association that has existed in the US since the American government annihilated the Bund!

______ 卐 ______

The new program was known as the ‘Twelve Points’. It presented a comprehensive outline for an American NS state. It included sections on the economy, education, agricultural policy, eugenics, culture, science, ecology and energy, as well as the expected call for racial unity and Aryan sovereignty.

A major theoretical development came in 1980, with the publication of Koehl’s groundbreaking essay, ‘The Revolutionary Nature of National Socialism’, Previously, the stated goal of National Socialism (going back to the era of NS Germany) was the defence of Western civilization. In this new work, however, Koehl declared that Western civilization had declined past the point of any rescue or recovery. Consequently, the proper goal of National Socialism was to prepare the way for a post-Western Aryan civilization. In retrospect, it can be seen that this essay was an ideological precursor to the 1983 transition from the NSWPP to the New Order, which will be discussed below.

The World Union of National Socialists

Koehl’s NSWPP continued participation in the World Union of National Socialists which Rockwell had helped to form a decade earlier.

In 1975, he made a successful organizational tour of Europe, where he contacted many Oldfighters of the NSDAP. Although some German National Socialists held the US movement in low regard, Koehl had built the NSWPP up to a point where they began to consider it in a more serious light.

Among those with whom he established connections were former Hitler Youth leader Arthur Axmann, Dr Hans Severus Ziegler, and Florentine Rost van Tonnigen (wife of the martyred Dutch NS leader). He also became friends with the NS pilots Hans Baur, Hans-Ulrich Rudel and Hanna Reitsch. Significantly, Koehl was the only American present at the funeral of the famous SS commander Otto Skorzeny.

Especially important, both to Koehl personally and the Movement, was the friendship that he established with Winifred Wagner, daughter-in-law of the renowned composer Richard Wagner and an early and continuing supporter of Adolf Hitler.

The decline of the NSWPP

In 1978, the party began another period of contraction. It was not that the party was doing anything differently, but rather that the mood of the country had changed. The social and political upheaval that had characterized the 1960s and early 1970s had faded away. That period had included such phenomena as Black rioting and ‘civil rights’ demonstrations; massive protests against the unpopular Vietnam War, the rise of the drug-oriented youth subculture and a general breakdown of traditional White society and values. This unrest and ferment alarmed many Whites and thus provided a fertile field for the growth of the NSWPP. But as the mood of the country shifted, the fortunes of the NS movement began to wane.

The election of Ronald Reagan as president in 1980 only intensified the deradicalization of White America. Many American Whites foolishly believed that Reagan would turn the clock back and reestablish White supremacy and traditional White values. Hence, some people who had previously supported the party now felt that the need for an extreme ‘Nazi’ alternative to the established order was unnecessary: they mistakenly believed that the System had fixed itself.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Exactly the same mistake that the more recent internet movements (‘race realism’, ‘white nationalism’, ‘alt-right’ or ‘alt-lite’, etc.) has been committing for decades!

______ 卐 ______

Party membership dropped off, donations declined, and it became harder to recruit qualified personnel for headquarters staff. Demonstrations became smaller and smaller, and it was more difficult to find candidates to stand for public office. Whether by coincidence or design, this period of party weakness also saw a rise in attacks on the Movement by the federal government. In particular, an effort was made by the Internal Revenue Service to bankrupt the NSWPP and seize its assets. Ultimately, Koehl was able to turn back these attacks, but only at an enormous cost that left the party drained of financial resources and energy.

Transition to the New Order

Koehl began to question whether the whole idea of gaining power under the banner of National Socialism was actually possible. It is true that he could build up the party – but only to a certain level. Rockwell’s original plan was for a sprint to power: he had hoped to become president by 1972. Now it was apparent that building an NS America was going to be more of a marathon race than a 50-yard dash. Consequently, a new approach was needed.

Matt Koehl was not just the leader of a movement on the fringes of polite society. He was also a thinker and theorist with a powerful intellect. Decades of reading and studying had convinced him that the problems facing the White nations of the world were deeper than even most National Socialists realized. It was not just a matter of the Jewish subversion of White society and the corrupt nature of the White elites. Rather, he felt, the very basis of Aryan society had been infected with alien spiritual values.

Consequently, efforts to gain political power by the Movement were ill-conceived. Even in the highly unlikely event that the party was able to outmanoeuvre and overpower its enemies, he reasoned, the diseased roots of White society would prevent the construction of a healthy NS state.

Western civilization was doomed, he believed, and there was no way that it could be rescued or saved. Rather, he felt, the proper focus for the National Socialist movement was to prepare the foundations for a post-Western Aryan civilization.

On January 1, 1983, Koehl dissolved the National Socialist White People’s Party and reorganized it as the New Order. While the NSWPP had been a political formation, the New Order was to have a spiritual or religious focus. In essence, Koehl was seeking to establish a whole new religion for Aryan humanity, which would provide a healthy basis upon which a future White civilization could be built.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: During the West’s darkest hour this step was understandable. Perhaps what Koehl lacked was the new information about the true origins of Christianity, a true apocalypse for whites (see our masthead)?

______ 卐 ______

The transition to the New Order was highly unpopular with many NSWPP comrades, and it led to a mass exodus from the Movement. Nevertheless, Koehl was convinced of the correctness of his decision and did not back down from implementing it, regardless of its popularity (or lack thereof) among his base of support. He strongly believed that it was his sacred duty to lead the Movement in the direction that he thought best, even if some comrades did not fully agree or understand.

Summing up the NSWPP

Even more so than the German-American Bund of the 1930s, Koehl created an organization that was a miniature American version of the NSDAP. But, paradoxically, that was both its strength and its weakness. What drew its members to it was a love and appreciation for Hitler and Hitler’s Germany. But this same focus on the past kept it from appealing to a wider audience.

The NSWPP had a split personality: On one hand, it was a highly ideological vanguard organization that demanded the utmost commitment from its members; on the other hand, it spent an enormous proportion of its slim resources appealing to the ordinary American Whites, who had no interest in Hitler or NS Germany. This was a contradiction that Rockwell had been attempting to resolve at the time of his death, but he had made only a tentative beginning in fixing it.

An example of this paradox was the stormtrooper uniform and the accompanying stormtrooper demonstrations. Certainly, the uniform was a force multiplier (to use a military term): a handful of troopers in uniform attracted many times more attention than the same number in civilian clothes. The publicity that the party received allowed the NSWPP to project itself in the public eye far beyond what its numbers would have otherwise allowed. But at the same time, the uniform was a barrier in terms of recruitment, as most Whites who were sympathetic to the party’s core message were unwilling to take part in uniformed public activities. The same could be said for the party’s outreach overall: only a tiny fraction of those Whites who agreed with the party were willing to join or participate because of its ‘Nazi’ image. Thus, the NSWPP was never able to actualize its full potential as a mass organization.

At the same time, focusing its energies and resources on spreading its message to a mass audience prevented the party from maturing as an elite vanguard formation. For one thing, many of those who did join up had unsuccessful lives or marginal personalities – that is, people who had nothing to lose. Such types were the opposite of an elite. They were allowed in, however, because they were the ones who were willing to participate in unformed demonstrations.

In its final years, the party did put an end to uniformed demonstrations. But it struggled to find activities to replace what had been its propaganda mainstay for over twenty years.

In some respects, the 1970s NSWPP was the high point of post-World War II American National Socialism. Other organizations with a belief system sympathetic to National Socialism have been larger, such as the White Patriot Party in the 1980s or the National Alliance in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But in terms of being a complete, open NS movement, none have surpassed the NSWPP.

As mentioned above, there were other NS, pro-NS or semi-NS organizations active in the United States during the same period that the NSWPP existed. These other groups combined had perhaps ten per cent of the strength of the NSWPP in terms of manpower and financial resources. With one exception, these groups were formed as a breakaway splinter of the NSWPP. Nevertheless, no survey of American National Socialism would be complete without mentioning them. These splinter groups will be the subject of the next instalment in this series.