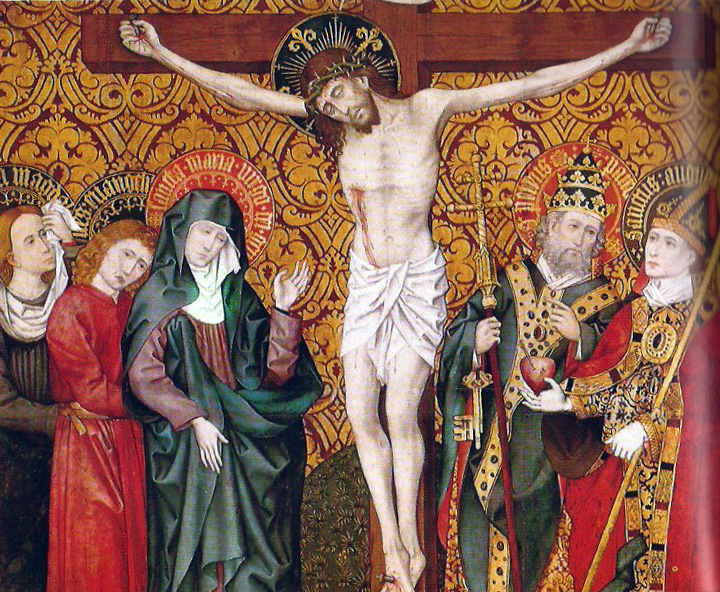

According to the theologians’ interpretation, the Church is born from the open side of Christ. It is the Church that congregates next to the cross of the Saviour in this painting of a Navarrese-French teacher at the Lázaro Galdiano Museum in Madrid.

The Imperial Church of Constantine and his successors always was a catholic, i.e. universal church. It is the institution that sanctioned universalism in the West. In ‘The Saxon Savior: Converting Northern Europe’ Ash Donaldson said:

______ 卐 ______

Universalism’s pyrrhic victory

It took centuries of relentless indoctrination to get the peoples of Northern Europe to extend the in-group boundaries outward to embrace, first, all those who said the words and bent the knee before the cross, and eventually all of humanity, whose encompassing by the true Faith is a Christ-given goal.

But at the moment of its greatest success, with European missionaries dispatched to the remotest corners of Africa and Asia, Christianity found itself assailed by the very universalism that had provided its appeal in the first centuries. The same weapons it had wielded to discredit the pre-Christian myths and folkways were now turned against it by the advocates of a universalism that had no need for something as quaint as deity. If, today, the notion of God seems less and less of a possibility to the rootless inhabitants of our soulless cities, it is partly because Christian universalism paved the way by making our tribal identities, ancient customs, and cherished myths ultimately irrelevant.

Today, with that thousand-year resistance behind us, we can see how the triumph of universalism, set in motion by a very different sort of savior in the fourth century BC, has gradually left us without a folk, without a polis, and without the means to even comprehend how fully life was once lived. All that remains, it seems, is to double down on Christian universalism, throw oneself instead into a substitute universalism such as Marxism, or chuck it all for an unabashed individualism.

Yet as the past century-and-a-half shows, ethnic identity has a habit of returning with a vengeance. Those who rediscover such myths, folkways, and traditions as have come down to us often find that these things strike a chord within them. They simply fit, without all the caveats and yes-but’s of syncretic universalism.

Ultimately, however, a folkish way of life must have a folk community, and not the virtual communities that exist only on social media. We must have a polis again, in all that the Greeks understood by that term: small, self-governing communities bound by common language, ethnicity, customs, and religious traditions. Such a thing, far from being utopian, would spring from our nature, life as it was lived across thousands of generations.

What is artificial is our divorce from the land, our crowding into cities to live alongside strangers for the purpose of endless consumption, and our insistence on universalism even when we ourselves—those of European descent—lose the most by it. In the long view, all this is fairly recent, and in the North, quite recent indeed. That should give us confidence, for though the line is frayed, it is far from broken.

____________

Bibliographical references appear in the original article.