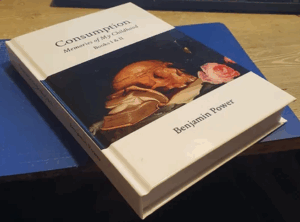

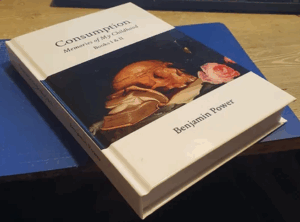

by Benjamin

Editor’s note: This is one of the new segments from the third edition of Ben’s autobiographical book (for context, see here):

______ 卐 ______

In time, my Mum ceased trying to defend me. Perhaps she changed her mind and began to doubt herself. More likely, she gave up in nervous strain under the force of Dad’s charming dishonesty and intellectual manipulations of the dialogues. I know around thispoint she had to start taking antidepressants herself, and, though she had put many complaints in to the doctors over their written words and their professional treatment of her, none were ever listened to. Part of me wonders if she turned a blind eye to my suffering in the house, desperate for her own sanity that it was not true.

In time, my Mum ceased trying to defend me. Perhaps she changed her mind and began to doubt herself. More likely, she gave up in nervous strain under the force of Dad’s charming dishonesty and intellectual manipulations of the dialogues. I know around thispoint she had to start taking antidepressants herself, and, though she had put many complaints in to the doctors over their written words and their professional treatment of her, none were ever listened to. Part of me wonders if she turned a blind eye to my suffering in the house, desperate for her own sanity that it was not true.

Either way, despite the strain of defending me, my mother betrayed me in the end by this cowardly abandonment of her duty towards me, much I do see how tough it would have been for her. These days she has gone back to her familiar patter of, “oh, his life has always been good, nothing ever happened” and “I simply don’t remember those days you mention”, if an outsider inquires after my home life, or if I turn to her and demand she account for Dad. Perhaps it is easier on her to exist in complete denial. Either way, it drives me to intolerable rage, knowing that there was a time once when she did stand up for me, only to have her spirit crushed out of her again by the cold, dispassion of idiotic medical staff. I pity her very much, but I cannot forgive her. She was my only hope.

For her part, the young therapist did not seem to mind so much that I was not in the family meetings. She noted down my “hostile and aggressive” manner, and continued with Dad, ladling pejorative labels on me, and mischaracterizing my “poor” behaviour, with me never there to defend myself, or to correct Dad’s second-hand reportage each week. The sessions continued weekly for over six months. Why on earth did she think I might be upset?! Was she stupid?! If she didn’t have the natural compassion to take my side as her patient and sole charge, why was she even working in psychological healthcare?! I cursed the day I had ever been put forward for them. By now though, the constant shaming I was subjected to, and the faulty opinion-making was beginning to take its toll, and my mind was indeed starting to come apart, my ego shattered, and my sense of cognitive calm fracturing at the edges. I felt divorced from the world, hanging in the cold, dim edges, like in fog, teetering on the abyss of something vast and deep. Most days I would cover this over, but the heightened anxiety was persistent, and, eventually, one day, I just cracked

Sitting again on the chair by my computer desk, in the middle of a dull, clouded afternoon, during a light rain storm outside, once more I took a strange fascination in my healing, much-abused right arm. Long-accustomed as I was to bending down and biting away at the area when in my lower moods, this time I approached from a far odder, more mechanical angle. To this day, I cannot remember what might have stressed me, if anything, worryingly. I think in general my life around that point was more than enough, even without anything specific to obliterate my mental wellbeing.

I had just finished eating my lunch for the day, an oven bake pepperoni pizza of the kind I had begun to consume on a regular basis for ease of preparation, and still had a sharp kitchen knife on my plate; one suitable for severing the crusts of my pizza, as well as a standard fork, and a teaspoon I had been using to gently separate the melted cheese (which I had never been much of a fan of long-term) from the base. Upon finishing my meal, something drew me again to my arm, not feeling any great distress, but somehow preoccupied, as if enticed.

Taking the relatively-sharp kitchen knife, I pushed down until the flesh popped, and carved deeply into my forearm skin, feeling little pain, perhaps on account of the severed nerve endings from long before, or maybe just from my daze itself, continuing in long grooves to shape out a rectangular ‘box’ around the outsides of my main healing area. When I had finished my ‘masking work’, blood trickling a little down my arm as it always did, I began to partition the flesh inside into cubes, cutting the little squares of epidermis into neat blocks, like a piece of raw tofu, but still attached to my lower dermis layers, and to the muscle underneath. No one came to disturb me that day, and so I worked slowly, for what felt like well over an hour, delineating the rectangle’s contents into neat parcels of meat, all in a line.

Once I had finished this task, I took the point of the knife again, and slit the hypodermis under my closest blocks away from the muscle layer, releasing little globs of subcutaneous fat – a grisly process where much pressure and repetition was required, and where I was obliged now and again to stop so I could snap down and suck up any excess blood. Eventually, the skin still sticking to the muscle in various places, I was able to stick my teaspoon under the excised flaps, and lever each cube up and off my arm, sometimes with a terrible tugging, and a fresh new splatter of blood.

Eventually, I was left with another wide hole in my arm – not desperately deep, but dark and bloody, in an expanse of ravaged veins, and ripped hair follicles, and otherwise the white strands of mangled flesh and fat – and beyond that, a heap of around forty small, soft, pinky-coloured guerdons, each just under 1cm x 1cm, sat on my plate in a pool of blood and clear-yellow bodily fluids.

With my fork, I proceeded to pick up each morsel of severed skin, and, in grisly auto-cannibalistic fashion, popped them one by one into my mouth, chewing for a long time on the gristle of each lump, like a mixture of pork rinds and stale bubble gum, and sucking the sweet, wet, sickly flavour out of the pieces of my own arm. Cooling blood trickled down past my chin. I don’t think I was thinking anything at all.

True, I had bitten my arm before, many times, but never had I stooped to actually consuming my own body, preferring instead to merely leave bite wounds or otherwise allow the skin to fall away unaddressed, and thankfully, this particularly gory and disturbing incident was never to be repeated.

When my mother did come in later and discover me, I cannot remember what was said. I can guess my parents’ reactions would have been total horror, an alien sensation. All I do remember is that I was taken down to the local surgery for an examination, and from there swiftly to Broomfield Hospital again, almost a second home to me by now, and of a similar surgical quality. Sitting in a waiting room to be examined by the doctors, it was as if in a surreal film. “So, why is the patient with us today?” I heard one of the ward staff say to another. “Oh, he cut off and ate a bit of his arm, apparently” was the seemingly unconcerned reply. Perhaps they too found it hard to register.

In the end, I was dressed, and sent home again (without psychological evaluation), and further notes made for my case-file, but, bizarrely, despite the severity of this hideous personal action, nothing was ever said of it to me in aftermath, and I do not remember my then psychiatrist ever taking any particular interest. There are a great many ‘blips’ like this in my record; times I would have thought pertinent to make at least brief mention of, if not to scrutinize intently. I can only assume they too would like somehow to brush them under the rug, surely some niggling opposition to their ‘it’s a brain disease so just take your meds and you’ll be fine’ argument. As it stands today, my prior history of extreme autophagia is never mentioned by any new psychiatrists I come into contact with, and certainly not by any of their day-to-day care workers. It’s as if they’ve purged it from my history, and like none of this ever happened. I find that a great, telling, frustration.

I wanted to run something by you. Please tell me if you think I’m not thinking straight on this.

I wanted to run something by you. Please tell me if you think I’m not thinking straight on this.