against the Cross, 13

If I were to write a cold but informative article, I would say that by 1879 Nietzsche’s health worsened with headaches, eye pains and continuous vomiting.

On 2 May he called in sick and gave up his professorship in Basel. He travelled for the first time to the Upper Engadine, where he spent his summers from that year onwards. He spent the winter in Naumburg with his family. In the early 1880s, he went to Riva on Lake Garda and later to Venice, where he studied Christianity intensively. Nietzsche spent August in Marienbad and the next couple of months in Naumburg. He then spent his first harsh winter in Genoa and in November published The Wanderer and His Shadow (added to Human, All Too Human). In 1881 he published The Dawn of Day and spent his first summer in Sils-Maria. In August he was assailed by the thought of the eternal return and in October he heard Bizet’s Carmen.

But I don’t like the informative style of encyclopaedias: it robs us of the real person and his inner experiences. The real Nietzsche then wrote things like ‘I can’t read, I can’t deal with people’. This flesh-and-blood Nietzsche implored his friend Overbeck, the theologian, to visit him: his wish was granted. Nietzsche’s joy was unbelievably great, as Overbeck later recounted.

These were times when Nietzsche had already established his mode of work as walking in solitude for several hours until his best thoughts came to him, which he would catch on the fly from his walks in his notebook. Rhode had distanced himself from the philosopher, but not from the person, the friend; and the pains in his eyes meant that even his mother had to read books to him on his visits to Naumburg.

Nietzsche was very depressed by the climate in his hometown. ‘Unfortunately, this year the autumn in Naumburg has turned out so cloudy and wet’, he wrote, where he continued to have horrible attacks of vomiting. ‘I can only endure the existence of walking, which here, in this snow and cold, is impossible for me’. To Overbeck, he wrote: ‘Last year I had 118 attacks’. But what is relevant for us was still the Wagner case, who, about his former friend, wrote in his notes: ‘Again one must be surprised at this apostasy’. On 19 October 1879, Wagner wrote to Overbeck:

How would it be possible to forget this great friend, separated from me?… It grieves me to have to be so totally excluded from taking part in Nietzsche’s life and notes. Would it be immodest of me to beg you cordially to send me some news about our friend?

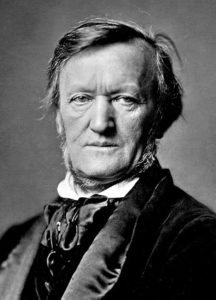

A week later the report of Nietzsche’s disconsolate state reached him. At the end of December Wagner dares to read The Wanderer and his Shadow and even reads some passages to Cosima. ‘To have nothing but derision for so lofty and sympathetic a figure as Christ!’, Richard exclaimed angrily.

The old composer was by then already in poor health, and like Nietzsche, he was burdened by the ‘permanently grey Bayreuth winter sky’, so he went to Italy for the winters. Nietzsche, for his part, spent four months with his new assistant, nicknamed Peter Gast, who read aloud to him: times for his book The Dawn of Day, which in some ways prefigures The Antichrist as far as the critique of compassion is concerned. (To try to understand Nietzsche we have to contextualise his philosophy in the present, where neo-Christian compassion taken to the extreme has led us to normalise pathologies such as those suffered by trans people: unwise levels of compassion that we have been calling ‘deranged altruism’. And the same can be said of Christian and neo-Christian love for marginalised black people: unbridled compassion.)

Like Wagner, even in 1881 Nietzsche also still loved his former friend, to the extent of confessing to close friends that if Wagner invited him to the premiere of Parsifal he would go to Bayreuth. But Wagner was repulsed by the whole course taken by Nietzsche. It is worth looking into the matter a little because the case has certain similarities with my tortuous relationship with the American racial right, and there is something I would like to clarify about the Jewish question.

First, while Nietzsche wanted to push for a supranational European spirit, Wagner believed in the Germanic character as a culturising force.

Here, Wagner was right, while Nietzsche didn’t seem to realise that the ethnic factor is fundamental. American racialists, from this comparison, are closer to Nietzsche than to Wagner because, unlike German National Socialism, American anti-Nordicists imagine a supranational Europe, all united under the banner of a chimaera they call ‘white nationalism’. Sebastian Ronin, the Canadian critic of the American racial right, was right to say that all nationalism is ethno-nationalism (just as Wagner and later Hitler believed as far as Germany and Austria were concerned). It follows that it makes no sense to grant amnesty to the mudbloods of the Mediterranean who have ceased to be properly white (or the mudbloods of Portugal, Russia, etc.).

Secondly, this is precisely why Wagner saw the emergence of the Jewish element as a threat when Nietzsche fantasised that Jewish capital would finance his anti-Christian works! Wagner supported the anti-Semite Adolf Stöcker, of whom Nietzsche would go so far as to write years later, when he lost his mind, that he should be shot!

Today, the impossibility of the collective Aryan unconscious to make a political movement in which, say, Swedes and Sicilians feel perfectly brotherly to the extent of making both a single empire, gives the lie to the precepts of so-called white nationalism in the US. Although Richard Wagner knelt before the cross, he was right on this point and Nietzsche was wrong. The Germanic race does matter, as does a healthy anti-Semitism.