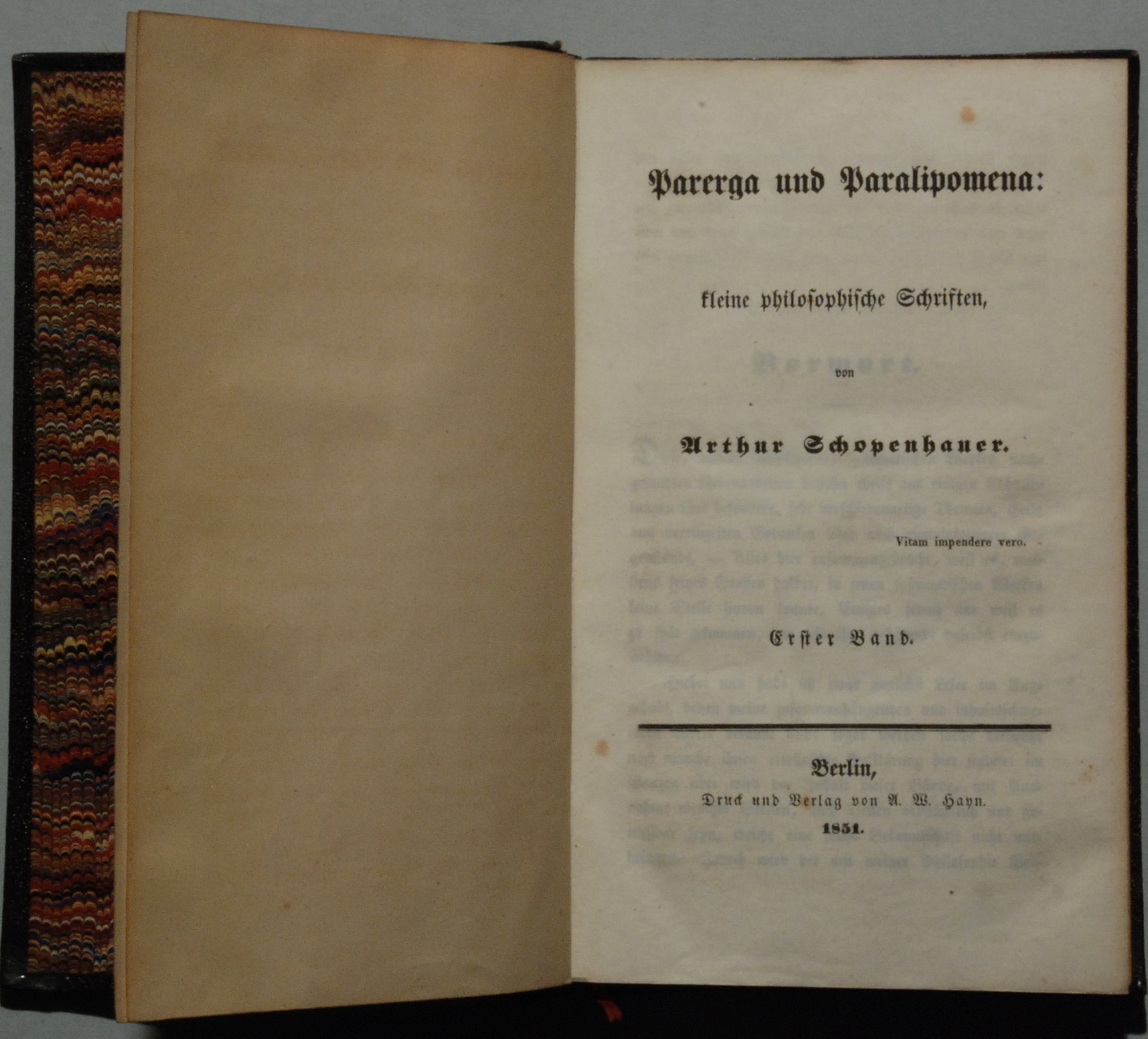

Parerga and Paralipomena, German original edition, 1851.

The day before yesterday I quoted a passage from Schopenhauer’s most readable book. This Christmas I would like to respond to what Gaedhal told me today. He says that the bourgeoisie leads to antinatalism and pessimism, and so does Christianity:

My task is to obliterate those forces that ruin the joy of life. The abusiveness of Christianity, of “our parents’ religion”, as you put it, is one of these malevolent joy-disrupting forces. This is where the Thanatos impulse comes from.

I believe the latter is the main factor, even more so than the bourgeois way of life. Let’s quote, for example, other paragraphs from Schopenhauer’s book, this time from the chapter “On Affirmation and Denial of the Will to Live”:

Between the ethics of the Greeks and the ethics of the Hindus, there is a glaring contrast. In the one case (with the exception, it must be confessed, of Plato), the object of ethics is to enable a man to lead a happy life; in the other, it is to free and redeem him from life altogether—as is directly stated in the very first words of the Sankhya Karika.

Allied with this is the contrast between the Greek and the Christian idea of death. It is strikingly presented in a visible form on a fine antique sarcophagus in the gallery of Florence, which exhibits, in relief, the whole series of ceremonies attending a wedding in ancient times, from the formal offer to the evening when Hymen’s torch lights the happy couple home.

Compare with that the Christian coffin, draped in mournful black and surmounted with a crucifix! How much significance there is in these two ways of finding comfort in death. They are opposed to each other, but each is right. The one points to the affirmation of the will to live, which remains sure of life for all time, however rapidly its forms may change. The other, in the symbol of suffering and death, points to the denial of the will to live, to redemption from this world, the domain of death and devil. And in the question between the affirmation and the denial of the will to live, Christianity is in the last resort right.

The contrast which the New Testament presents when compared with the Old, according to the ecclesiastical view of the matter, is just that existing between my ethical system and the moral philosophy of Europe.

The Old Testament represents man as under the dominion of Law, in which, however, there is no redemption. The New Testament declares Law to have failed, frees man from its dominion, and in its stead preaches the kingdom of grace, to be won by faith, love of neighbour and entire sacrifice of self [emphasis added]. This is the path of redemption from the evil of the world. The spirit of the New Testament is undoubtedly asceticism, however your protestants and rationalists may twist it to suit their purpose.

Asceticism is the denial of the will to live; and the transition from the Old Testament to the New, from the dominion of Law to that of Faith, from justification by works to redemption through the Mediator, from the domain of sin and death to eternal life in Christ, means, when taken in its real sense, the transition from the merely moral virtues to the denial of the will to live.

My philosophy shows the physical foundation of justice and the love of mankind, and points to the goal to which these virtues necessarily lead, if they are practised in perfection. At the same time it is candid in confessing that a man must turn his back upon the world, and that the denial of the will to live is the way of redemption. It is therefore really at one with the spirit of the New Testament, whilst all other systems are couched in the spirit of the Old; that is to say, theoretically as well as practically, their result is Judaism—mere despotic theism.

In this sense, then, my doctrine might be called the only true Christian philosophy—however paradoxical a statement this may seem to people who take superficial views instead of penetrating to the heart of the matter.

The heart of the matter is Xtian ethics! It is striking that, despite not being a Christian, Schopenhauer shared such Christian principles. This is what makes him, in our eyes, a “secular Christian” (what Gaedhal calls a hyper-Christian atheist).

The fact that this secular philosopher made such concessions to the religion of his parents would prompt the next great German philosopher, Nietzsche, to delve into the root of the matter. Among other neochristians, Nietzsche criticised Schopenhauer, whom he had admired in his early youth.

10 replies on “Pessimism”

It is not surprising, then, that once Christianity was secularised, after 1945 (the ultimate defeat of pagan values) the neochristians turned to ethno-suicidal pessimism.

I’ve never understood pessimism at a cosmic scale as a coherent philosophy separate from despair – even navel-gazing solipsism. It seems somehow selfish and subjective as opposed to the will of collective thinking. Putting the race above one’s self…

My own philosophy comes neither from the Old Testament’s Law nor the New Testament’s Redemption (which again, feels self-obsessed). I think the best we can hope for in life is not to seek happiness on a personal level but to seek the fulfilment of duty. All this will to live – for the sake of one’s own eudaimonia – is again subjective, individualistic thinking, and serves us no good as a race (rather like by analogy the pitfalls of insular capitalism).

I think my position is the realistic one, perhaps the most pragmatic one, given that we are in a dark age, and any concessions to personal pleasure are a distraction from the near-insurmountable task we face, and must complete. So yes… not to wash your hands of the world, or seek dislocation from it, as with suicidal Buddhism, but not to stringently tolerate it as it is either, with that shoddy OT Law in need of thorough dismemberment to make way for the return of an augmented better paradigm.

I have no love for mankind, but I think it is clear – perhaps on account of this – that our duty is to carry out a grand exterminationist campaign against all worthless bipeds so that, in future times, perhaps the pursuit of personal happiness will, for the first time in our history (I don’t believe in any prior Golden Age) not be a flippancy, the world finally settled and suited to that goal. Life is not yet for pleasure, but to get something done, despite all hardship and personal misery, and with the only living matter available that can do such, and all other considerations must be passed aside until the completion of this vital mission. A highly selective, non-pathological altruism, for a common good.

All thought of death is worthless! The Aryan race is worth more than the ‘sanctity’ and self-gratification of any one soul!

(perhaps my thoughts are shaped by the cold fact that I’ve never really had a chance to cultivate pleasure in my own barren life, thwarted from very early on, and thus thoughts of comfort or the retention of bourgeois living standards have never really obsessed me)

Let’s illustrate this with an anecdote. The vegetarian restaurant where I eat at Christmas closed down. I went to a street stall on the corner near my house: a popular one.

Although I ordered tlacoyos with mushrooms, nopales, and green beans, I was stunned by what a dozen people next to me were eating: tlacoyos with beef brains, tripe, and chicken.

Exterminating the Neanderthals is life’s number one priority indeed. Only then can we enjoy, in a “Florentine Fete”, the beauty of the young Aryans who, as our Führer wanted, will be vegan.

Editor's Note: I've moved Gaedhal's comment to the proper thread, here.So you will be holding a gun to millions of white children’s heads and forcing them to eating revolting vegan slop that we didn’t evolve to subsist on, then? You’re as zealous as a Christian, determined to force a square peg into a round hole.

I’ll let your comment slide since I mentioned you in a recent post. But I won’t bother replying in detail: Ben already did in another thread. (In any case, it’s inconceivable that such beautiful Aryans as those in the image above have any slaughterhouse in their paradise.)

What’s wrong with hunting a wild boar with spear and bow amidst the columns of an enchanted forest? Your idyllic world already has a few hundred thousand bipeds to begin with, slaughterhouse are a separate issue to eating meat.

I am not talking about the past, but about the future (cf. Arthur C. Clarke’s first novella).

On the occasion of your article about feeling lonely when it comes to our ideologies:

Personally, loneliness is killing me on this front. I feel ideologically isolated, especially with feminism and women having taken over and now ruling the planet. And let’s not forget Black people and also the lower races who are an even bigger obstacle than Blacks because their numbers are larger and they’ll never admit their inferiority.

Our cause was doomed from the start.

Robert: Have you read the novel The Turner Diaries (cf. Ben’s words above: “grand exterminationist campaign”)?