extermination, 11

Editor’s note:

“We have to fight to secure the existence and expansion of our race and of our people; to enable them to nourish their children and to preserve the purity of their blood; to secure the freedom of our Fatherland”.

—Hitler

Unlike the movies, the drama did not end with the extermination of the prehistoric Neanderthals. The rest of the hairy hominids that didn’t undergo the genetic changes that led to the ‘naked ape’ had to be exterminated.

Alas, after the passages quoted in the previous instalment (#10), Vendramini’s book falls apart. Like the normie Tom Holland, whose book Dominion helped me understand how Christianity transmuted into neochristianity, Vendramini is also a slave to Christian/neochristian ethics. That is why in the final chapters, despite his professed atheism, Vendramini insists that contemporary humanity is one. In fact, Danny Vendramini had probably the most iconic last line in this book with saying “there is no them and us. It’s all an illusion. There is only us.”

To combat this claim, it is useful to familiarise oneself with Jared Taylor’s books on racial realism, and better still, with the first chapter of Pierce’s Who We Are. It is this first chapter, in which Pierce discusses prehistory, that serves us well in building a bridge between what we have seen so far in Them & Us and history.

Although Vendramini’s book has been truly wonderful up to this point, from the paragraph in which the last Neanderthal was exterminated onwards, the rest of his chapters must be taken with caution (“there is no them and us…”).

Even so, given that a priest of the sacred words longs to ensure the beauty of our females (the drive that motivated the prehistoric exterminators!), some subsequent passages in Vendramini’s book are relevant to understanding that the work of extermination only began with Cro-Magnon man. And had it not been for the greatest historical blunder committed by the Anglo-Americans, Himmler and the SS would have continued the work of eugenics in territories that shouldn’t belong to the Russians but to the Germans who would have fulfilled their Master Plan East.

In the chapter following the one in which, in southern Spain, the last Neanderthal suffered the fate of the dodo, Vendramini wrote:

______ 卐 ______

This hypothesis proposes that top of the hit list for eradication on six continents were deviants and those perceived to be the others. Theoretically, this could mean anyone who triggered a Neanderthal teem. Pragmatically though, it could include anyone who looked different. If your nose was too flat, your eyeballs not white enough, your pupils not circular enough or your lips too thin, you were at risk of being subconsciously perceived as a Neanderthal—and treated as such. In a world where first impressions were often a matter of life and death, coming across as dumb, crass, humourless or gruff was likely to get you killed. And because nothing creates a first impression better than posture, having a stooped (monkey-like) gait, hunched shoulders or a head that jutted forward on your shoulders was a recipe for a short life.

Because artificial selection was almost exclusively exercised by men, females would be more prone to scrutiny than males. If girls were considered too flat-chested, straight-waisted, wrinkled, thin-lipped, or if the labia protruded beyond the vulva, they would be less likely to pass on their genes.

It was as if these spontaneously self-forming death squads had all been issued with the same orders. And the same hit list. From Spain to eastern Mongolia, and from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego the same motley collection of ill-formed deviants became the target of this sustained campaign of lethal selection. Although it is sometimes argued that ‘death squads’ only emerged in the 1970s and 1980s in South America, they have existed under different guises since prehistoric times. The all too familiar lament of ‘the day men came with guns’ to rape, murder and pillage has its antecedents in the Mesolithic, when men came with flint-tipped spears—to line up the innocents and make their lethal selection. But had a CSI unit of forensic pathologists examined the bodies, they would have seen a pattern to the victims. The selection was anything but random. By this simple expedient, a unique homogeneous human physiology and behavioural repertoire began to emerge simultaneously around the world. This blunt, brutal but chillingly effective scenario is, along with mate selection derived from Neanderthal teems, the only evolutionary scenario that can explain how and why modern humans are today one species.

Learning to dance

As a result of this lethal form of artificial selection, behaviours that had previously provided little or no contribution to fitness (like the ability to dance, hold a tune or laugh at a joke) now assumed an adaptive function. When a Cro-Magnon raiding party descended on a community, the villagers’ ability to speak fluently, decorate their bodies or even crack a joke could mean the difference between living and dying. This brings new meaning to conformity—and to being ‘human’. If Neanderthals were thought of as an artless, humourless, crass bunch, then art, tattoos, music, dancing, laughter and singing would become reliable indicators of us.

This generated pressure for everyone to acquire these external identifying signifiers. Men and women began wearing jewellery, tattooing their bodies and painting them with red ochre because they found these cultural accruements to be like passports—facilitating free and safe movement.

Cro-Magnons invented musical instruments and played them as a stamp of their humanity. They told stories, brewed alcoholic drinks and sang songs around the campfire. And they painted pictures on cave walls and fashioned ivory into figurines. Back in the Mesolithic, ‘artistic’ was not an affectation or indulgence—it was a much admired survivalist skill that could very well save your life. Styling their locks, embellishing clothes, tools and weapons—in effect, ‘making a fashion statement’—became ingrained in the human psyche as an adaptive behaviour. In a very real sense, the Cro-Magnons were the first slaves to fashion.

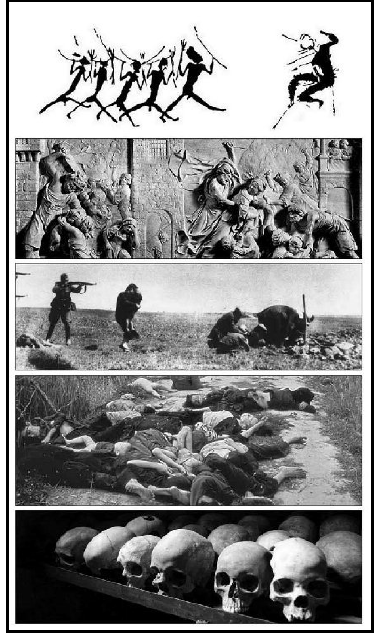

Intergroup violence is so pervasive in human history, we tend to take it for granted. (From top) a prehistoric drawing of archers and victim from a cave in Castellón, Spain; the biblical massacre of the innocents; the shooting of Kiev Jews by Nazis; the My-Lai massacre by American troops in Vietnam; and skulls of the victims of the Rwandan genocide.

Designer babies

There is every reason to believe that the relentless selection process included newborns. Neonates displaying atypical characteristics were ‘soft targets’ and infanticide was unquestionably the simplest, most cost effective application of artificial selection.

This tells us that the most dangerous time in the life of a Cro-Magnon was immediately after birth. That was when the males would inspect each baby and euthanise any infant they considered beyond the norm. This blunt policy of infanticide probably concentrated on conspicuous Neanderthaloid indicators such as the amount of body hair, facial wrinkles, head size and body fat.

For example, while birth is a challenge for most primate species because of the large size of the foetal head compared to the pelvis, the wide birth canal in chimps and gorillas and the small head size of their babies normally allows safe, unassisted delivery. This predicts that Neanderthal females also had wide hips and small-headed babies to make birth easier and safer.

Applying the differentiation hypothesis predicts that selection pressure would be generated for a larger head size in Cro-Magnon neonates. But even if a large head proclaimed to the tribe that a newborn was ‘one of us’, this reassurance came at a price. If the baby’s head was too big, neither mother or infant would survive. […]

Eliminating the competition

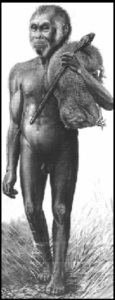

The theory that blind senseless violence—that most loathsome of human proclivities—has played a pivotal role in the emergence of modern humans by eradicating vestigial Neanderthaloid remnants from the Cro-Magnon genome, may be disagreeable. However, the model now goes even further. It predicts that as Cro-Magnons colonised Africa and Asia, they inevitably encountered ancestral hominid populations such as Homo floresiensis (below) and Homo erectus. The model proposes that the perceived deviancy of these indigenous people would also trigger them and us teemic responses, that would predispose Cro-Magnons to treat them as if they were Neanderthals, even though they had never seen a real Neanderthal. In other words, the hotchpotch campaign of sexual selection and artificial selection that they applied to one another would now be applied to other species of Homo they came across.

Once labelled generically as them, indigenous hominid species would be subject to the full force of Cro-Magnon aggression. With inevitable consequences.

Once labelled generically as them, indigenous hominid species would be subject to the full force of Cro-Magnon aggression. With inevitable consequences.

Could this explain what happened to all those pre-existing populations of hominids and early modern humans spread across Asia, Africa and the Americas? The archaeological evidence certainly confirms that, while there were numerous hominid species living from Africa to Asia before the arrival of Cro-Magnons, once the Cro-Magnons arrived, they all disappeared. The first to vanish were two species of Homo erectus—one in China, the other in Indonesia.

Until then, erectus had been probably the most successful hominid species of all, a tenacious hunter-gatherer who had survived for 1.75 million years and colonised half the globe.

For ages, it was believed that Homo erectus—thought to be the first hominid species to leave Africa—became extinct long before modern humans arrived in their areas. But we now know this is not the case. Recent dating of fossilised bones and artefacts reveals one population of erectus held out on the isolated island of Java until as recently as 25,000 years ago. This coincides with the time humans reached Java. After that, Homo erectus disappears from the fossil record.

Their new cognitive capacity enabled Cro-Magnons to build seaworthy vessels and cross the Timor Sea to Australia. The earliest widely-accepted date for their arrival in Australia is around 38,000 years ago, but a recent review of the data suggests occupation as early as 42,000–45,000 years ago.

When Cro-Magnons arrived, there appears to have been at least one other hominid species already living in Australia—in the south of the continent. Known as the Kow Swamp people, they had relatively large and robust bodies and thick skulls indicating they were related to Homo erectus. It’s thought the Kow Swamp people arrived when there was still a land bridge between Australia and Asia.

The Kow Swamp people appear in the fossil record about 20,000 years ago, and then abruptly disappear. Given that Cro-Magnons entered Australia from the north and the isolated Kow Swamp lived in the south, it is conceivable that the two groups did not make contact for thousands of years. NP theory suggests that when they finally did, the humans promptly wiped them out.

Whether humans were also responsible for the extinction of the diminutive Homo floresiensis—the ‘Hobbits’—on the remote island of Flores in Indonesia about 13,000 years ago, is also impossible to confirm. But again, anthropologists Peter Brown, Michael Morwood and their Indonesian colleagues, who discovered and named floresiensis, argue that they were contemporaneous with modern humans on Flores. This makes them the longest-lasting hominid (apart from humans), outlasting the Neanderthals by about 12,000 years. It also highlights Peter Brown’s claim that these resilient species of the genus Homo may have been direct descendants of australopithecus (like ‘Lucy’), one of the earliest African hominids. If so, then these resilient little fellows managed to survive in a unbroken line for a whopping five million years. Until, that is, modern humans arrived on their island. Once humans arrived, floresiensis abruptly disappeared.

This represents only circumstantial evidence of genocide and requires more proof, but some points are unequivocal. Firstly, by 13,000 years ago, of the at least seven—and possibly dozens, or even hundreds—of different subspecies of hominids which had inhabited the world, there remained only one. Secondly, their disappearance occurred only after the arrival of modern humans. Thirdly, because all other species became extinct, everyone living today can trace their ancestry to the original population of Cro-Magnons in the Levant. In effect, this ‘purification’ of the gene line was evolution by genocide. As an instrument of artificial selection, it was systematic, methodical and extremely efficient. Modern humans owe their present homogeneity to the thoroughness of the genocidal eradication of anyone considered too deviant to fit into the Cro-Magnon culture.

____________

N.B. You can read the first 35 pages of Vendramini’s book here.