extermination, 7

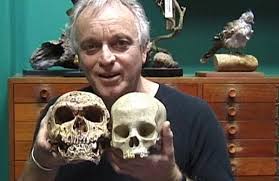

Vendramini shows that Neanderthal eyes were not only higher on the skull than ours, but were also much larger.

Chapter 19: Natural born killers

“I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”

When all the strategic adaptations described in the last chapter are added to the defensive adaptations humans acquired earlier, the result is something that looks very much like a fully modern human. This is not a coincidence. As disagreeable as it may be, this combination of aggressive, murderous, devious, cruel, sexually repressive, devilishly clever and patriarchal characteristics is a substantial part of what define us as a species. These characteristics distinguish modern humans from their stone-age ancestors and from every other primate. Thousands of timid archaic humans went into the population bottleneck, and only a handful of ferocious, militaristic modern humans came out.

Transforming into the most virulent species on earth is what it took for humans to throw off 50,000 years of persecution. Only a superior predator could have reversed the predator-prey dynamic. And only by transforming into something more lethal and dangerous than Neanderthals themselves, could those early humans stake their claim to the top rung of the food chain.

From an evolutionary point of view, the struggle to reverse the predator-prey dynamic (despite being fuelled by genocidal rage) wasn’t personal. It was simply a rudimentary and spontaneous expression of ‘survival of the fittest’.

The Levantine reversal set the tumultuous course of human evolution for the next 50,000 years, honing the strategic adaptations that transformed the Skhul-Qafzeh humans from timid to triumphant, from fearful to fearless. It was here that the die was cast, from which all future humans would be forged. The Levantine humans had become something without precedent in the animal kingdom. For the Eurasian Neanderthals, this new breed of humans must have seemed like Frankenstein monsters, so different were they from their timorous predecessors. To comprehend the sinister nature of the human transformation, I am reminded of something the father of the atomic bomb J. Robert Oppenheimer said when he witnessed the first nuclear denotation. He quoted a line from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”.

Phoenix rising

With its red and gold tail plumage, the phoenix is a beautiful bird from Phoenician mythology that was said to live for 500 years. When it is about to die, it builds a nest of cinnamon twigs, nestles in, and sets fire to itself. When the firebird is completely consumed, a new phoenix rises magically from the ashes.

This mythic tale of resurrection and regeneration provides a fitting analogy for what happened to the Skhul-Qafzeh humans. The catharsis of Neanderthal predation decimated their numbers, devastated their lives, and drove them to the precipice of extinction. But just as they were about to disappear forever, enough strategic adaptations took hold to fan the embers and allow a few resolute souls to emerge—belligerent, deadly and looking for revenge.

This scenario of resurrection and retribution encapsulates two major tenets of the strategic adaptation hypothesis and, coincidently, provides two predictions that can be used to test the theory. The first is that strategic adaptations fixed during the population bottleneck transformed Skhul-Qafzeh humans into recognisably modern humans with a new Upper Palaeolithic culture. Secondly, this allowed the post-bottleneck humans to reverse the ancestral predator-prey relationship and go on a genocidal rampage of retribution against their ancestral foe.

If the first prediction is correct, the fossil record of the Levant should show that Upper Palaeolithic culture suddenly appeared there between 50,000 to 46,000 years ago. And it does. The Upper Palaeolithic transition first shows up in the fossil record about 47,000 years ago, which is when NP theory proposes that modern humans were emerging from the population bottleneck. Secondly, a plethora of solid archaeological evidence confirms the Levant is the site of the earliest systemic transition from Middle Palaeolithic to Initial Upper Palaeolithic anywhere in the world.

Most of the recognised indicators of modern behaviour are there—including prismatic blade technology, the transport of raw materials over long distances, complex multi-component tools (including, for the first time, bone and ivory tools), personal ornaments, specialised subsistence strategies, language capacity, symbolic notation systems, and so on.

The hypothesis argues that the gradual accumulation of new strategic adaptations created a tipping point that resulted in a new species.

One of the methods that biologists use to determine if two populations are the same species is to check whether they interbreed. Even if they look very similar, if they don’t interbreed it’s a sure sign they’re different species. For example, Cope’s Gray Treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and the Gray Treefrog (Hyla versicolor) are visually indistinguishable. The only distinctive thing that separates them is their singing voices, but this is enough to prevent them interbreeding and so they’re classified as separate species.

So because the Levantine humans that emerged from the bottleneck were no longer subject to sexual predation and interbreeding with Eurasian Neanderthals, they were now a sexually isolated breeding population. If Neanderthal males came around looking for females, they would now be given short shift. The days of predation were over.

More to the point, though, the post-bottleneck Levantines were physically and behaviourally so different from their pre-bottleneck ancestors as to be virtually unrecognisable. This indicates that a speciation event took place. They were no longer Skhul-Qafzeh. Indeed they would probably look down on Skhul-Qafzeh folk as dumb, timid brutes with whom the prospect of interbreeding would be repulsive. In every respect, the post-bottleneck people were now effectively a new species. But what species?

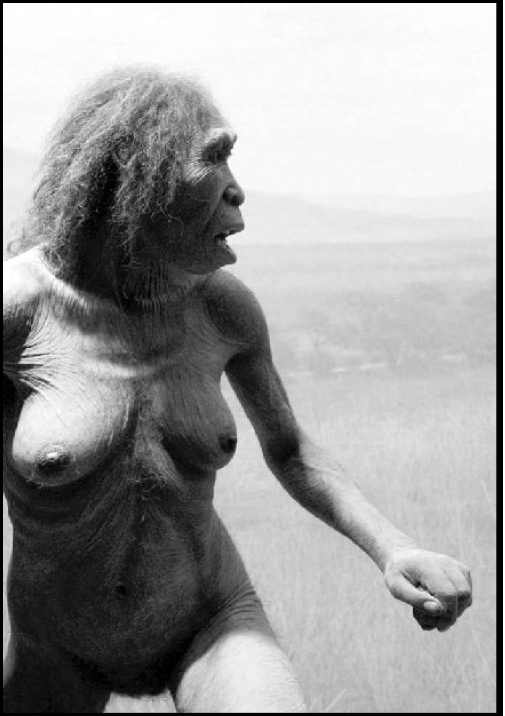

This figure from the Natural History Museum in New York is described as a reconstruction of Homo ergaster, a hominid species that lived in Africa between 1.9 and 1.4 million years ago. However, NP theory asserts that this is what humans looked like 50,000 years ago.

The black sheep of the family

Although they possessed many characteristics of fully modern humans of today, when it came to outward appearances the post-bottleneck modern humans were most likely quite different from both their pre-bottle-neck ancestors and fully modern humans. For a start, they had slightly larger brains (1600cc compared to 1400cc for today’s humans) and as a predator species, acquired a more robust skeletal-muscular physiology, so they looked bigger and beefier than fully modern humans. And, according to anthropologist Vincenzo Formicola’s analysis of the data, the males were considerably taller (at 176.2 cm) than their predecessors. In other words, this was a transitional morphology—not quite Skhul-Qafzeh, but not quite fully modern human.

Were a crowd of these post-bottleneck humans to appear on the high street today, we might be surprised by how visually different they were from us. Overall these post-bottleneck humans would convey a disconcerting impression. We would probably consider them brutish, ill-formed, hairy and uncouth. And, because their faces appear unbalanced (asymmetrical), we would probably judge them unattractive (even ugly) by modern standards. They are after all, still stone-age cavemen and women.

But it would be their behaviour more than anything else that would make them conspicuous. Over thousands of years of continual interspecies warfare, natural selection had retained the toughest, most aggressive, resilient, merciless individuals. Clearly the selection for aggression and risk-taking was directed primarily at adolescent and young adult males who were the ones doing most of the fighting. One simple mechanism of selection focused on males with abnormally high levels of hormones such as testosterone, which has been shown to increase verbal and physical aggression in young males.

By a simple application of Darwinian theory, an hypothesis emerges which proposes that the continual selection for aggression in young males (because it was so adaptive) would gradually produce a cohort that was so innately aggressive and predisposed to violence that a new word was needed to describe them. Modern terms like hooligans, ruffians and even barbarians won’t do. Modern descriptions of male group violence are inadequate for these post-bottleneck people, who existed before rules, civilisation, or even humanity as we know it. Their exceptional level of aggression was selected for because it was adaptive. It wouldn’t be today. Only in the context of a war of unimaginable barbarity against a ferocious enemy would this level of aggression be necessary or warranted.

To distinguish this unprecedented level of male aggression, I use the term hyper-aggressive. It describes a repertoire of extreme behavioural responses that emerged in response to the aberrant environmental circumstances prevailing at the time. Male hyper-aggression includes a suite of teemic traits that, in addition to negligible impulse control and aggression, also includes paranoia, callousness, ruthlessness, sadism and absence of empathy, remorse and love.

In 1941, Hervey Cleckley, a psychiatrist with the Medical College of Georgia, described a similar list of personality traits and behaviours in modern humans and called it ‘psychopathology’. There can be little doubt that your average post-bottleneck male would be classified as a psychopath according to diagnostic criteria developed by Robert Hare from the University of British Columbia, the current world authority on the subject.

However, it’s important to put the psychopathology of these early modern humans into context. They lived in a time before morals and ethics existed, so of course it follows that they were immoral and unethical. Romantic love was still in its infancy. Empathy for anyone beyond the family or the tribal group was practically anathema. And having a conscience, feeling guilty or empathising with one’s victim was not only useless, it was almost certainly maladaptive.

____________

N.B. You can read the first 35 pages of Vendramini’s book here.

One reply on “Neanderthal”

This mythic tale of resurrection and regeneration also offers an analogy for what happened to Benjamin and me. The catharsis of parental predation decimated our spirits, devastated our lives, and brought us to the brink of psychic extinction. But just when we were about to go mad forever, enough strategic adaptations occurred in our being’s nucleus to render us belligerent, lethal, and vengeful (cf. my seventeen-year-old soliloquy, quoted in Letter to mom Medusa: “Woe to the world if I get out of this…”).