A religion for sheep, 2

by Revilo P. Oliver

Published by Liberty Bell Publications in 1980,

under Oliver’s nom de guerre Ralph Perier.

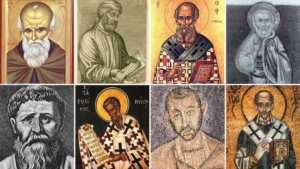

The Fathers of the Church

Today, including all of the many minor sects, is what it was made by the patient and subtle work of the Fathers of the Church. They were a knavish lot. There is no way of knowing how many of them were actually Jews on duty for God’s Race. It is highly unlikely that any one of them was a Greek or Roman. Most of them were probably Semites or descendants of one of the other Oriental peoples that swarmed into the mongrelised Roman Empire and displaced or replaced the Romans. Whatever their racial antecedents, it is clear from their own writings, despite much later whitewashing, that they were a motley crew of shysters, psychopaths, and other misfits. They were calculating or compulsive liars and forgers; see the able review of their record by Joseph Wheless, Forgery in Christianity (New York, 1930).

One of the Fathers’ most audacious and successful hoaxes certainly emits a Jewish odour. By brazen affirmation constantly repeated, they put over the claim that the wicked Romans, beginning in the time of Nero, persecuted Jesus’s little lambs because the innocent creatures wanted to worship “the true God.” Nothing could be more absurd historically. The Romans, aside from their typically Aryan obtuseness to the facts of race, were an admirably practical people and knew how to govern. It was their fixed policy never to interfere with the superstitions of their subjects. They impartially tolerated the most grotesque rites and obscene religions. Some of the disgusting cults that flourished among the dregs of society practised human sacrifice, but so long as they were content to sacrifice their own members, the Romans took no action: They knew that nothing should be done to save fools from the consequences of their folly. It was only when religious zeal inspired the murder of Romans or of the subjects entitled to their protection that the Romans drew a line beyond which their toleration would not go. Even then, they punished, not the pernicious faith, but only violence and conspiracy to commit violence.

The vermin executed by Nero were Jewish terrorists from the rabble of the huge ghetto that the Jews had planted in Rome. They were accused of having set the great fire that destroyed the greater part of Rome in 64; they confessed and were executed—cruelly, it is true. When one considers the appalling outbreaks of Jewish nihilism that occurred throughout the world from time to time, whenever a christ stirred up the rabble, one sees that it is highly probable that the terrorists were guilty of the crime to which they confessed. It is true that Nero’s political opponents, who were conspiring to overthrow him, preferred to accuse him of the crime; and the young egomaniac’s arrogant folly, when he expropriated the devastated centre of the city for an extravagant new palace, seemed to confirm the political propaganda. That was what enabled the Fathers, when they began to impose their hoax on the ignorant more than a century later, to pretend that the ferocious terrorists had been persecuted for wanting to love everybody.

When historical criticism became feasible in our eighteenth century, the Fathers’ clever hoax long escaped detection: Thirteen centuries of Christianity had so accustomed our people to the practice of torturing and killing men for their thoughts and superstitions that the story seemed plausible enough.

After the middle of the third century, when the successors of the extinct Romans tried desperately to shore up the crumbling empire, a few of them are known to have taken some action against Christians as such, but we do not know under what provocation and, of course, no reliance can be placed on the tales told by the Fathers. The usual policy, however, was toleration, and we know that Diocletian admitted Christians to positions of high trust and responsibility in his own palace until 303, when the Christians’ piety got the better of them and they tried to murder him by burning him alive in his own bedroom. That made him angry.

At the end of the fourth century, St. Jerome, who was much better educated than most of the Fathers and probably the best of a bad lot, was the real founder of a new type of short story that became immensely popular: tales about the “martyrs” who “suffered for their faith.” There is extant a letter by Jerome in which he bitterly reproves some Christians who thought that it mattered that the hero of his first fiction had never existed. That, Jerome indignantly said, was irrelevant, since his tale edified the clergy’s customers, who knew no better. And Jerome went on concocting the tales with such brilliant success that he soon had a host of imitators, all trying to invent more grisly plots.

Jerome, as you see, was an accomplished theologian. He is now best remembered for his revision of the Latin text of the Bible, which he carried out with the help of kindly Jews, who hovered about him, eager to explain the mysteries of God’s Word. Those Jews, we may be sure, knew what Christianity was doing for them.

In 313, Constantine and his colleague, Licinius, who were jointly fighting civil wars against rival emperors, issued the so-called Edict of Milan, which proclaimed universal toleration for all religious cults and specifically named the Christians as cults to be tolerated. The two emperors undoubtedly felt that the support of the Christian organisations would be an asset in the civil wars, and Constantine may have foreseen that they could be especially useful to him when the time came for him to turn upon and destroy his ally and brother-in-law, Licinius. Of course, as soon as Constantine was safely dead, the Fathers of the Church concocted a story that he had been privately “converted” by a childishly-imagined miracle in 312, and had been actually baptised on his death bed, so that the soul of one of the most treacherous rulers undoubtedly flitted right up to Jesus.

A fourth-century head of Constantine, which clearly shows not only the degenerate appearance of its subject, but also the decline of Classical art that had already taken place. Art would decline even more precipitously after the Christians’ rise to complete power. It would not attain greatness again until the rediscovery of Classical ideals and philosophy during the Renaissance.

Christians still like to repeat the myth about the “conversion” of Constantine and the Triumph of the True Faith. All that really happened was that the Fathers of the Church, securely established by the edict of toleration, shrewdly used their bargaining power in intrigues with the various ambitious generals who were slugging it out for the grand prize. The real triumph of their Church came only with the final victory of Theodosius in 394, when the Fathers at last got the power to use the imperial police and army to begin persecuting in earnest. Their first concern, of course, was to exterminate their Christian competitors and destroy all their gospels. Some of those gospels, however, escaped them in one way or another. That is why we now know a good deal about the competing brands of Christianity.

We Aryans still have an instinctive respect for honesty and a peculiar respect for facts. We are shocked by the hypocrisy and mendacity of the Fathers, and Christians of our race cannot bring themselves to believe those ostentatiously pious individuals were what the record shows them to have been. In justice to them, however, we should remember that their deceptions were not un-Christian. They thought—or at least it was their business to teach—that Salvation depended on belief in certain inherently implausible tales and on conduct they approved. From that premise, it followed that any lie or trick that would induce the desired faith in the yokels was not only justified, but meritorious. As a recent writer has said, “Lying for the Lord is a normal exercise of piety.”

One reply on “Xtianity:”

See also pages 13-14, the contents pages, of our translation of Christianity’s Criminal History.