against the Cross, 10

Nietzsche was never entangled in the cobwebs of what, misleadingly, Bertrand Russell would later call ‘Wisdom of the West’ (in reality, the philosophy of the Christian era had only been mental darkness). Nietzsche knew this, as he wrote in On the Pathos of Truth about the true lovers of wisdom: ‘Such people live in their own solar system’. Such sovereign independence was the antithesis of the mental illness that Kant’s apotheosis had meant in Germany, a folie en masse that even Schopenhauer was infected by. The new philosopher ‘speaks in forbidden metaphors and unheard-of complexes of concepts in order at least to respond creatively, by destroying and mocking the old conceptual barriers’. This new ‘philosopher, insofar as he poeticises, knows; and insofar as he knows, poeticises’: a liberating vindication of the Id against the ogre of the neo-theologians’ Superego.

Nietzsche was never entangled in the cobwebs of what, misleadingly, Bertrand Russell would later call ‘Wisdom of the West’ (in reality, the philosophy of the Christian era had only been mental darkness). Nietzsche knew this, as he wrote in On the Pathos of Truth about the true lovers of wisdom: ‘Such people live in their own solar system’. Such sovereign independence was the antithesis of the mental illness that Kant’s apotheosis had meant in Germany, a folie en masse that even Schopenhauer was infected by. The new philosopher ‘speaks in forbidden metaphors and unheard-of complexes of concepts in order at least to respond creatively, by destroying and mocking the old conceptual barriers’. This new ‘philosopher, insofar as he poeticises, knows; and insofar as he knows, poeticises’: a liberating vindication of the Id against the ogre of the neo-theologians’ Superego.

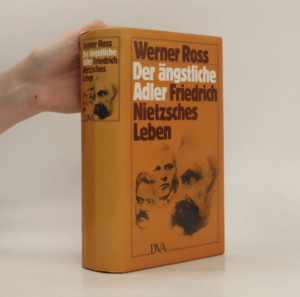

Thus, in Nietzsche’s mind, an innovation emerged: that of the philosopher-poet. And since one of his pillars was pre-Platonic philosophy, Heraclitus became his philosopher-artist. Years later, in Ecce homo, Nietzsche would come to confess that he felt more at home with Heraclitus: the philosopher of the burning of worlds from whom he would draw—oops!—his own metaphysics: that of the eternal return. It was already the time when Nietzsche was beginning to cultivate a thicker moustache than in his earlier years. And before he came up with the word Umwertuung (transvaluation), in his personal notebook we can read about the new philosopher: ‘If he found a word which, if uttered, would destroy the world, do you think he wouldn’t utter it?’ As Stefan Zweig would write in Der Kampf mit dem Dämon, this man, who was not yet thirty, already knew that he had a daimon inside him. Werner Ross comments:

Nietzsche found himself slowly and painfully. Decisions matured: separation from Wagner and separation from the university. Both measures were necessary to achieve full independence and to face what awaited him which he himself defined as ‘the sorrows of truthfulness’. But he was an anguished eagle [hence the title Der ängstliche Adler] and, equipped as he had long been with the weapons of a bird of prey, he preferred to return to the home nest [spend some time in Naumburg]. The heroic had been applied to his soft temperament with violence: with cold water and unheated rooms, with swimming trials [in a lake] and a lot of early rising, with a lot of study and sexual abstinence.

Nietzsche, who had no contact with young girls, suffered from bodily ailments, perhaps psychosomatic in that, until the onset of madness in later times, Christmas was a critical time for his depression. In an attempt to cure himself, he wrote to his friend Malwida: ‘Now I wish for myself, in confidence, a good woman very soon, and then I’ll consider the wishes of my life to be fulfilled’. Meanwhile, the visionary Wagner believed that the symphony was to be replaced by his musical drama (Wagner didn’t call his works ‘operas’). And he somewhat was right, for with the advent of cinema—musical dramas with new technology—soundtracks would replace the conventional symphony genre.

I don’t want to recount all the anecdotes about the eleven days Nietzsche later spent in Bayreuth, recorded lightly in Cosima’s diary, except that at one point Wagner ‘became very angry and spoke of his longing to find in music something about the superiority of Jesus Christ’, as Ross writes. Suffice it to say that Nietzsche had dared to have brought a Brahms score! Later, when Nietzsche sent them his essay Schopenhauer as Educator, the Wagners received the text with delight. Richard wrote to him: ‘I have thought that you should either marry or compose an opera; both would be useful to you. But marriage seems better to me’ and invited him once more to his home. Unfortunately, Nietzsche declined the invitation because he wanted to go on a pilgrimage to a high, lonely Swiss mountain. What he had in mind was to fulfil the role of the new philosopher: ‘When there is much to destroy, in times of the chaos of degeneration, it is most useful’.

But Nietzsche lamented that he didn’t yet know how to fly. For the moment the young eagle could only flap its wings, and he confessed that he was staggering backwards in the face of the immense free space, but that the day would come ‘to soar as high as a thinker has never soared before, to the pure air of the Alps and the ice’. And more telling still: ‘Or, to leave absolutely no doubt as to what I mean, when it matters unspeakably more the appearance of a philosopher on earth than the persistence of a State or a university’.

Shortly afterwards he would be thirty years old.