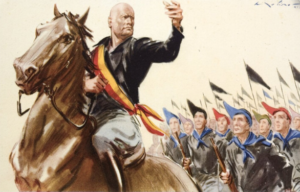

[Hitler] enthused about Italy, where Mussolini and his fascists seized power in late October 1922 through his iconic ‘March on Rome’. Shortly after, Hitler remarked coyly: ‘one calls us German fascists’, adding that he did not want to go into ‘whether his comparison is true’. He was soon more forthright, demanding ‘the establishment of a national government in Germany on the fascist model’. A year later, he told an interviewer from the Daily Mail that ‘If a German Mussolini is given to Germany, people would fall down on their knees and worship him more than Mussolini has ever been worshipped.’

Hitler now broke with the mainstream nationalist and revisionist consensus, which demanded that Italy surrender German-speaking South Tyrol. He argued that any new ‘national government’ would only be able to establish itself if it secured some major victories. These would be hard to achieve on the economic front, Hitler believed, and so the best bet was the incorporation (Anschluss) of Austria. This would require not only British but Italian approval. Moreover, Germany should align itself more generally with Mussolini’s Italy, ‘which has experienced its national rebirth and has a great future’. For both of these reasons, he condemned the ‘palaver’ about South Tyrol of the other nationalists in the strongest terms, emphasizing that ‘there are no sentiments in politics, only the cool calculation of interest’.