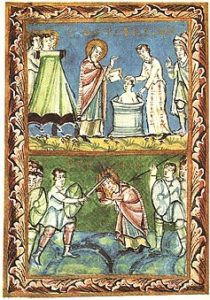

On 5 June 754, after twenty-five years of ministry, Boniface together with his choral bishop of Utrecht, and fifty companions were killed by the Frisians of Dokkum on the Doorn, fiercely defended by his men, in the fight of ‘arms against arms’ (Vita Bonifatii), as befits the Christians. Uselessly he held over his head ‘the holy book of the gospels’ against the deadly blow.

And in a genuinely Christian manner, in ‘the land of the infidels’ burst ‘at once the swift warriors of future vengeance, well-kept but unsatisfied guests’ (sospites sed indevoti hospites), as the priest Willibald of Mainz wittily puts it, inflicting ‘an annihilating defeat on the pagans who confronted them’. The Frisians fled, ‘were beaten down in a huge mass, and turning their backs they lost their goods, estates and heirs with their lives. But the Christians returned home with the spoils of women, children, servants and handmaids of the idolaters’ (Vita Bonifatii).

Isn’t that a joyful and pious religion? Especially when the Frisian survivors of the plunder, the enslaved women and children terrified by murderers, ‘and by divine punishment’, embraced the faith of the one whom they had killed. Traces of this persist to this day in Fulda.

Of course, this is only a half-truth. The whole truth is told by the priest Willibald at the end of the eight chapter of his Vita (the ninth and last chapter is ‘a later addition’—Rau). The point is that, then, many miracles overflowed there:

Where the sacred corpse had been deposited… divine favours overflowed abundantly. And all who came there, afflicted with the most diverse diseases, found health of body and soul through the intercession of the holy man. So that some, whose bodies were almost completely dead, who were almost exanimate and seemed to be breathing their last breath, regained their former health; others, whose eyes were covered with blindness, recovered their sight, and still others who, imprisoned in the snares of the devil, had their spirits troubled and had lost their reason, obtained the primitive freshness of spirit.

And all this thanks to ‘the champion in the race of the spirit’. And, as is to be expected and as Willibald’s work concludes, ‘through the Lord, to whom be glory and honour for an eternity of eternities. Amen’.

Unfortunately, we haven’t finished with Christianity. On the contrary, by now it is developing more and more magnificently. While Boniface committed to the popes, the popes made a commitment for themselves. And for them the most important factors of power were still, above all, the Byzantines and the Longobards.