Perhaps the notion of the irrevocable ‘existence’ of the past is of little consolation to those tormented by nostalgia for happy times, lived or imagined. Time refuses to suspend its flight at the plea of the poet enamoured of fleeting beauty—whether it be an hour of silent communion with the beloved woman (and, through her, and beyond her, with the harmony of the spheres), or an hour of glory, i.e. communion, in the glare of fanfares or the thunder of arms, or the roar of frenzied crowds, with the soul of a whole people and, through it and beyond it, again and again, with the Divine: another aspect of the Divine.

It is possible, sometimes, and usually without any special effort of memory, to relive, as if in a flash, a moment of one’s own past and with incredible intensity, as if one’s self-consciousness were suddenly hallucinated without the senses being the least bit affected. A small thing—a taste, very present, like that of the petite Madeleine cited by Proust in his famous analysis of reliving; a furtive odour, once breathed in; a melody that one had thought forgotten, a simple sound like that of water falling drop by drop—is enough to put, for an instant, the consciousness in a state that it ‘knows’ to be the same as the one it knew, years and sometimes decades, more than half a century earlier; a state of euphoria or anxiety, or even anguish, depending on the moment that has miraculously re-emerged from the mist of the past: a moment that had not ceased to ‘exist’ in the manner of things past, but which suddenly takes on the sharpness and relief of the present, as if a mysterious spotlight directed the daylight of the living actuality.

But these experiences are rare. And if it is possible to evoke them, they do not last long, even in very capable people of evoking their memories. Moreover, they only concern—except in very exceptional cases—the personal past of the person who ‘revives’ such a state or such an episode, not the historical past.

Yet there are people who are much more interested in the history of their people—or even that of other people—than in their own past. And although scholars, whose job it is to do so, succeed in reconstructing as best they can, from relics and documents, what at first sight appears to be the ‘essentials’ of history, and although some scholars sometimes astonish their readers or listeners by the number and thoroughness of the details they know about the habits of a particular character, the intrigues of a particular chancellery, or the daily life of such and such a vanished people, it is no less certain that the past of the civilised world—the easiest to grasp, however, since it has left visible traces—escapes us.

We know it indirectly and in bits and pieces, that our investigators try to put together, like a game of patience in which half or three-quarters of the puzzle are missing. And even if we possessed all the elements, we would still not know it, because to know is to live, or re-live, and no individual subjected to the category of Time can live history. What this individual can, at most, know directly, that is to say, live, and what he can then remember, sometimes with incredible clarity, is the history of his time insofar as he himself has contributed to making it; in other words, his own history, situated in a whole that exceeds it and often crushes it.

This is undoubtedly a truer story than the one that scholars will one day reconstruct. For what appears to be the ‘essence’ of an epoch, studied through documents and remains, is not. What is essential is the atmosphere of an epoch, or a moment within it: the atmosphere that can only be grasped through the direct experience of someone who lived it: one whose personal history is steeped in it. Guy Sajer, in his admirable book The Forgotten Soldier, has given us the essence of the Russian campaign from 1941 to 1945.

______ 卐 ______

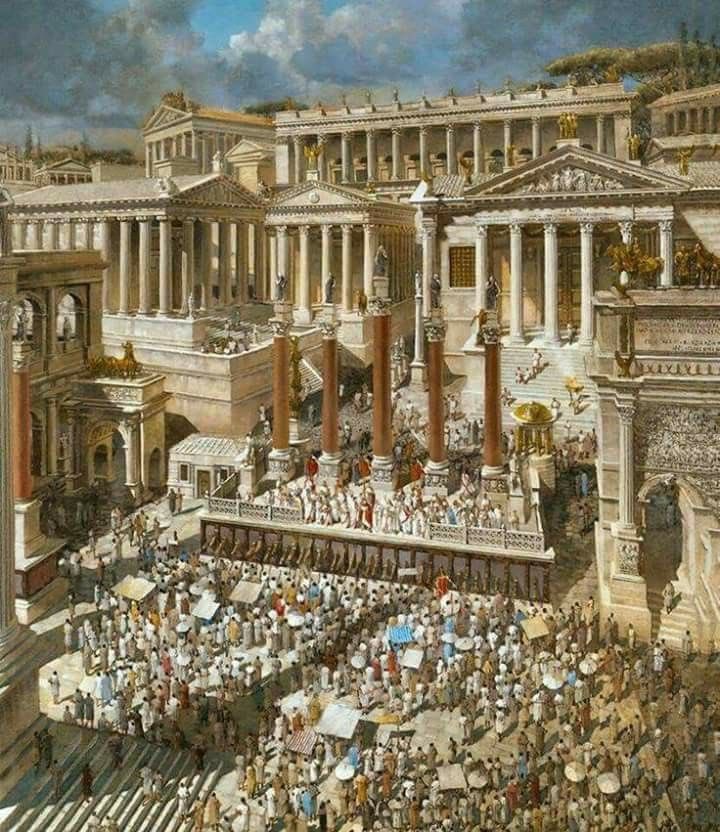

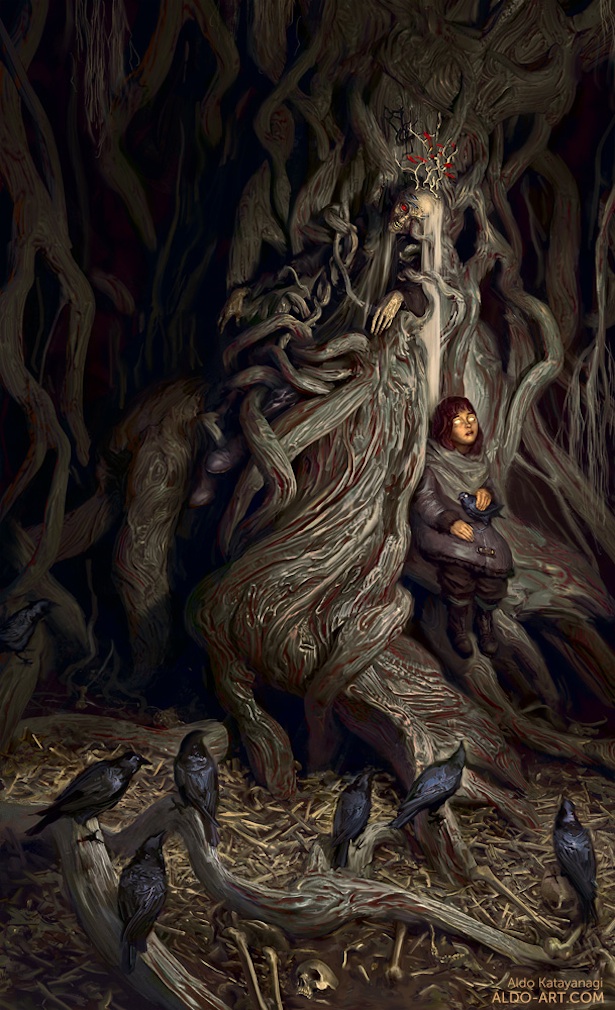

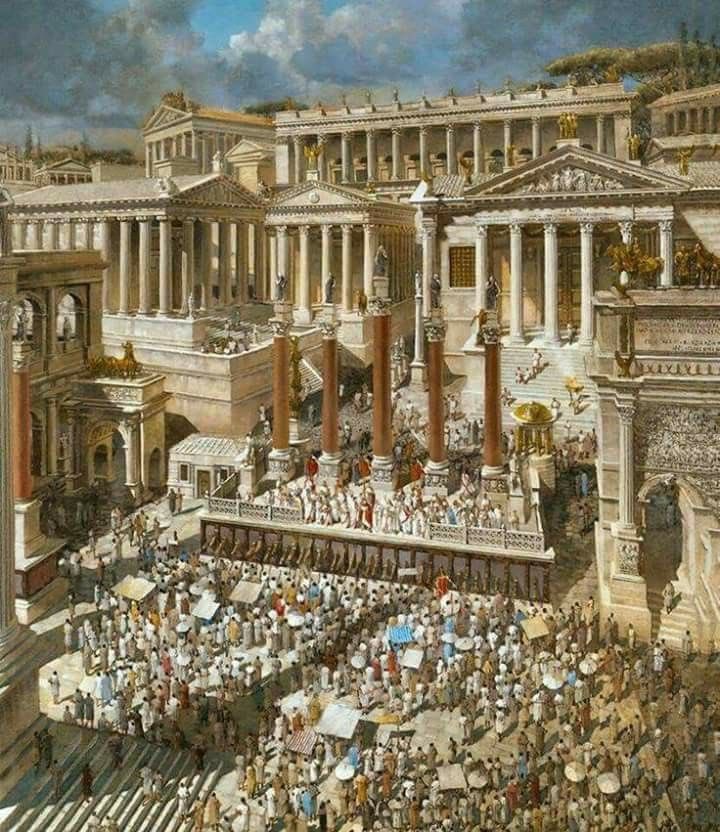

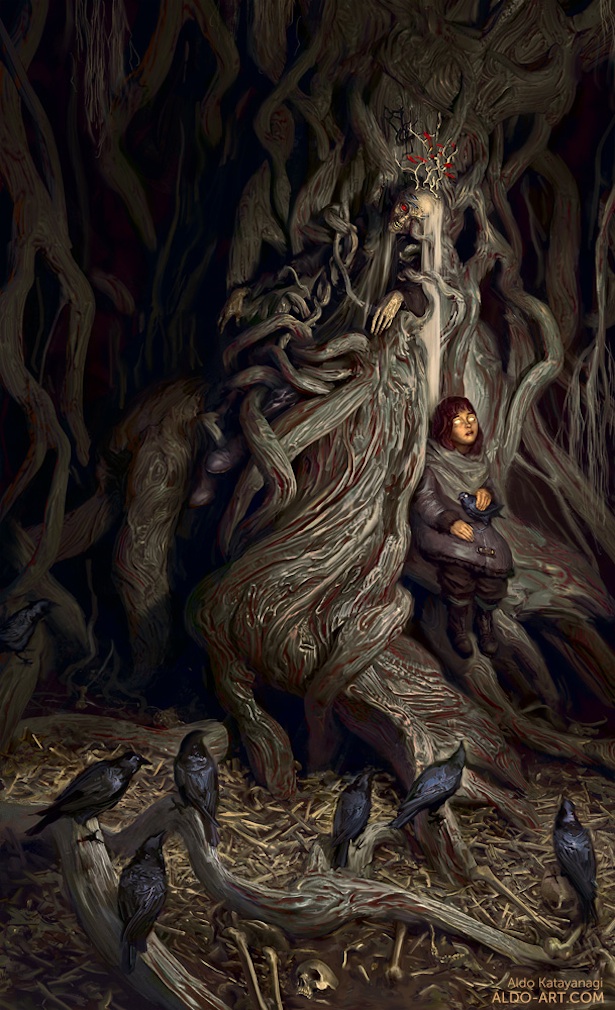

Editor’s Note: This is absolutely true. One of the reasons why I prefer lucid essays like the one by Evropa Soberana on the Judean war against Rome (the masthead of this site) to the scholarly book that Karlheinz Deschner wrote about that epoch, is that Soberana transports us to that world—as in another literary genre Gore Vidal’s Julian has transported us to 4th-century Rome. Academic books are extremely misleading in that they don’t transport us back in time. We desperately need the visuals of what happened. That’s why I like the metaphor of the last greenseer, Bloodraven: the man fused to a tree that could see the past.

______ 卐 ______

He was able to put in his pages such a force of suggestion, precisely because, along with thousands of others in this campaign of Russia in the ranks of the Wehrmacht, then in the elite Grossdeutschland Division, it represents a slice of his own life.

When, three thousand years from now, historians want to have an idea of what the Second World War was like on this particular front, they will get a much better idea by reading Sajer’s book (which deserves to survive) than by trying to reconstruct, with the help of sporadic impersonal documents, the advance and retreat of the Reich’s armies. But, I repeat, they will acquire an idea of it, not a knowledge, much in the way we have one today of the decline of Egypt on the international scene at the end of the 20th Dynasty, through what remains of the juicy report of Wenamon, special envoy of Ramses XI (or rather of the high priest Herihor) to Zakarbaal, king of Gebal, or Gubla, which the Greeks call Byblos, in 1117 BC.

Nothing gives us a more intense experience of what I have called in other writings the ‘bondage of Time’ than this impossibility of letting our ‘self’ travel in the historical past that we have not lived, and of which we cannot therefore ‘remember’. Nothing makes us feel our isolation within our own epoch like our inability to live directly, at will, in some other time, in some other country; to travel in time as we travel in space.

We can visit the whole earth as it is today, but not see it as it once was. We cannot, for instance, actually immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of the temple of Karnak—or even only one street in Thebes—under Themose III; to find ourselves in Babylon at the time of Hammurabi, or with the Aryas before they left the old Arctic homeland; or among the artists painting the frescoes in the caves of Lascaux or Altamira, as we have somewhere in the world in our own epoch, having travelled there on foot or by car, by train, by boat or by plane.

And this impression of a definitive barrier—which lets us divine some outlines but prohibits us forever a more precise vision—is all the more painful, perhaps, because the civilisation we would like to know directly is chronologically closer to us, while being qualitatively more different from the one in whose midst we are forced to remain.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: In my fantasy that such a thing as the Wall existed, and have the last greenseer as our tutor, I imagine that I would spend an inordinate amount of time visiting ancient Sparta, and other cities where the Norse race remained unpolluted for centuries.

Editor’s Note: In my fantasy that such a thing as the Wall existed, and have the last greenseer as our tutor, I imagine that I would spend an inordinate amount of time visiting ancient Sparta, and other cities where the Norse race remained unpolluted for centuries.  I would visit all the temples of classical religion not only in Greece but in Rome, trying to capture through their art the Aryan spirit in its noblest expression.

I would visit all the temples of classical religion not only in Greece but in Rome, trying to capture through their art the Aryan spirit in its noblest expression.

But above all I would pay close attention to the human physiognomy of living characters before they mixed their blood with mudbloods.

Only he who actually sees the past as it was, has a good grasp of History.

The saddest thing of all is that pure Nordids still exist, but the current System is doing everything possible to exterminate them (as in Song of Ice and Fire the children of the forest was a species on the verge of extinction).

______ 卐 ______

History has always fascinated me: the history of the whole world, in all its richness. But it is particularly painful for me to know that I’ll never be able to know pre-Columbian America directly… by going to live there for a while; that it will never again be possible to see Tenochtitlan, or Cuzco, as the Spaniards first saw them, four hundred and fifty years ago, or less, that is to say yesterday. As a teenager, I cursed the conquerors who changed the face of the New World. I wished that no one had discovered it so that it would remain intact. Then we could have known it without going back in time; we could have known it as it was on the eve of the conquest, or rather as a natural evolution would have modified it little by little over four or five centuries, without destroying its characteristic traits.

But it goes without saying that my real torment, since the disaster of 1945, has been the knowledge that it is now impossible for me to have any direct experience of the atmosphere of the German Third Reich, in which I did not, alas, live.

Believing that it was to last indefinitely—that there would be no war or that, if there were, Hitlerian Germany would emerge victorious—I had the false impression that there was no hurry to return to Europe and that, moreover, I was useful to the Aryan cause where I was.

Now that it is all over, I think with bitterness that only thirty years ago[1] one could immerse oneself immediately, without the intermediary of texts, pictures, records, or comrades’ stories, in that atmosphere of fervour and order, of power and manly beauty, that of Hitlerian civilisation. Thirty years! It is not ‘yesterday’, it is today: a few minutes ago. And I have the feeling that I have missed very closely both the life and the death—the glorious death, in the service of our Führer—that should have been mine.

But one cannot ‘go back’ five minutes, let alone 1500 years or 500 million years, into the unalterable past, now transformed into ‘eternity’—timeless existence. And it is as impossible to attend the National Socialist Party Congress of September 1935 today as it is to walk the earth at the time when it seemed to have become forever the domain of the dinosaurs… except for one of those very few sages who have, through asceticism and the transposition of consciousness, freed themselves from the bonds of time.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: ‘I saw your birth, and that of your lord father before you. I saw your first step, heard your first word, was part of your first dream. I was watching when you fell. And now you are come to me at last, Brandon Stark, though the hour is late’…

‘Time is different for a tree than for a man. Sun and soil and water, these are the things a weirwood understands, not days and years and centuries. For men, time is a river. We are trapped in its flow, hurtling from past to present, always in the same direction. The lives of trees are different. They root and grow and die in one place, and that river does not move them. The oak is the acorn, the acorn is the oak’ (Boodraven to his pupil in George R.R. Martin’s A Dance with Dragons).

‘Time is different for a tree than for a man. Sun and soil and water, these are the things a weirwood understands, not days and years and centuries. For men, time is a river. We are trapped in its flow, hurtling from past to present, always in the same direction. The lives of trees are different. They root and grow and die in one place, and that river does not move them. The oak is the acorn, the acorn is the oak’ (Boodraven to his pupil in George R.R. Martin’s A Dance with Dragons).

[1] This was written in 1969 or 1970.

But I still love to play with the idea even if it is pure fantasy. The ultimate truth about Time is unclear, and while parapsychologists have failed to scientifically prove their claims, that doesn’t automatically mean that extrasensory cognition doesn’t exist. It just means that there is no reliable evidence yet.

But I still love to play with the idea even if it is pure fantasy. The ultimate truth about Time is unclear, and while parapsychologists have failed to scientifically prove their claims, that doesn’t automatically mean that extrasensory cognition doesn’t exist. It just means that there is no reliable evidence yet.