‘Breaker of Chains’ is the third episode of the fourth season of HBO’s fantasy television series Game of Thrones, and the 33rd overall.

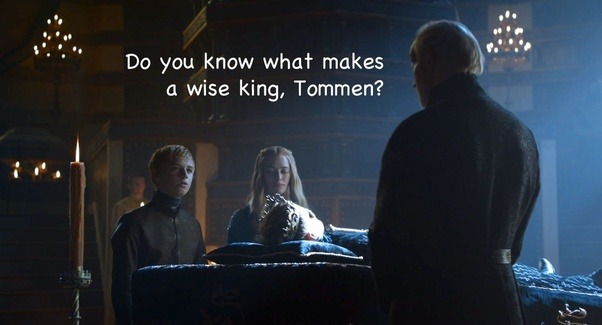

A scene from the episode that we see right in the place of the photo above, when Tywin and his grandson Tommen leave it, caused an incredible hysteria among the cretinous fandom of the series.

Right there, on the floor below Joffrey’s corpse, Jaime almost rapes Cersei: a mortal sin for woke people, although the real sin of the siblings Jaime and Cersei had been to engender, incestuously, former king Joffrey and the future king Tommen (something that Tywin ignores). Even more serious is what Cersei said before the lustful Jaime jumped on her. Without any proof, this evil woman said that Tyrion had been the one who poured poison in Joffrey’s cup (in fact, it was Littlefinger in collusion with Olenna Tyrell). But that unfounded accusation didn’t scandalise the cretinous fandom.

I don’t want to focus on the fandom’s hysteria that caused the purported rape scene in this episode, but on the dialogue between grandfather and grandson. Less than a year ago I said that the philosophical problem of who should govern arose from the times of Plato’s The Republic, and that in popular culture only Martin apparently has dealt with the idea of the philosopher-king as we can watch in this scene, transcribed below:

Tywin: ‘Your brother is dead. Do you know what that means?’

Tommen: ‘It means I’ll become King’.

Tywin: ‘Yes, you will become King. What kind of King do you think you’ll be?’

Tommen: ‘A good King?’

Tywin: ‘Huh. I think so as well. You’ve got the right temperament for it. But what makes a good king, hmm? What is a good King’s single most important quality?’

Tommen: Holiness?

Tywin: Hmmm… Baelor the Blessed was holy. And pious. He built this Sept [the cathedral in Martin’s universe seen in the above image]. He also named a six-year-old boy High Septon [a kind of Pope in Martin’s world] because he thought the boy could work miracles. He ended up fasting himself into an early grave because food was of this world and this world was sinful.

Tommen: Justice.

Tywin: Huh. A good king must be just. Orys the First was just. Everyone applauded his reforms. Nobles and commoners alike. But he wasn’t just for long. He was murdered in his sleep after less than a year by his own brother. Was that truly just of him? To abandon his subjects to an evil that he was too gullible to recognise?

Tommen: What about strength?

Tywin: Hmmmm… strength. King Robert was strong. He won the rebellion and crushed the Targaryen dynasty. And he attended [only] three small council meetings in seventeen years. He spent his time whoring and hunting and drinking until the last two killed him.

So, we have a man who starves himself to death; a man who lets his own brother murder him, and a man who thinks that winning and ruling are the same thing. What do they all lack…? [rhetorical pause]

Tommen: Wisdom.

Tywin: Yes! But what is wisdom, Hm?

Last month I mentioned Yezen and below I quote from his video ‘Why Bran Stark will be King’, which was uploaded twenty days before the grand finale. Note that Yezen’s words were uttered in YouTube during the show’s eighth and final season, and that he was the only fan of Game of Thrones who correctly predicted who would become king at the end of the series:

On a fundamental level, Game of Thrones is an exploration of power, and different characters coming to power convey different messages about what it takes to rise up in the world.

The rise of Daenerys [called ‘Dany’ by her lover Jon] emphasises strength and justice and ambition. Jon champions honour and righteousness. Someone like Littlefinger, deception and opportunism, while Cersei emphasises ruthlessness and vanity. Meanwhile, King Brandon would convey a more mysterious meaning that, although strength, lineage, deception and ruthlessness each play a part, all of them are bound up by fate.

This ending would serve as a strange marriage of idealism and cynicism. In many ways, Bran begins the story as the most powerless character, lacking even basic bodily autonomy. And as fate would have it, Bran ends up the most powerful. Yet that power comes at the cost of isolating Bran from his own humanity, and never gives him the thing that he really wanted.

And look, I know you probably still don’t buy it, or you still think it’s gonna be Jon [crowned king in the finale], and you really might be right about that, but hear me out just a little longer, because there is a glimmer of idealism to this ending.

Though many will die, and the wheel [Dany’s metaphor for the feudal system] might not break, Bran just might make a good king after all. Despite having lost so much of himself to the Three-eyed Raven [see my posts about this character: here], Bran, perhaps more than any other character, has grasped one of the most essential lessons of the story, which is the importance of empathy.

Despite their history, Bran is able to look at Jaime Lannister, the man who once shattered his life, and to see good in him, to see Jaime as a man who was protecting the people he loved. And to not only forgive him, but to protect him. This simple act of understanding demonstrates what the war-torn kingdoms of Westeros have been so lacking: not strength, or cunning, or even honour, but real wisdom.

For a world that’s been so damaged by people’s inability to see from one another’s perspective, maybe a broken boy is the right ruler to heal a broken kingdom. Maybe not the one you want, certainly not the one we’d expect, but the one the ending needs.

The only problem is, Martin hasn’t published the last two novels in his series. And while he did tell the producers how his A Song of Ice and Fire saga would end, it would still be better to have Martin’s books if he ever does finish them. As we’ll be seeing in future posts this is the topic I’m passionate about Game of Thrones, not what the cretinous fandom cares about: whether or not Jaime raped Cersei in this episode.