‘The Catholic clergy has a good part of the responsibility for unleashing the wars of extermination of the time. The influence of the Church reached the last village’.

—Berthold Rubin, Das Zeitalter Iustinians (1960).

Editors’ note: Here I reproduce some translated excerpts from a chapter about the extermination of two Germanic peoples in the 6th century: one of the unheard of crimes of Christianity because, until now, almost all church historians had been Christians (like the Jews, Christians lie by omission). To contextualise this entry see instalments 121, 122 and 123 of the same series.

______ 卐 ______

The Catholic clergy in favour of a crusade against the Vandals

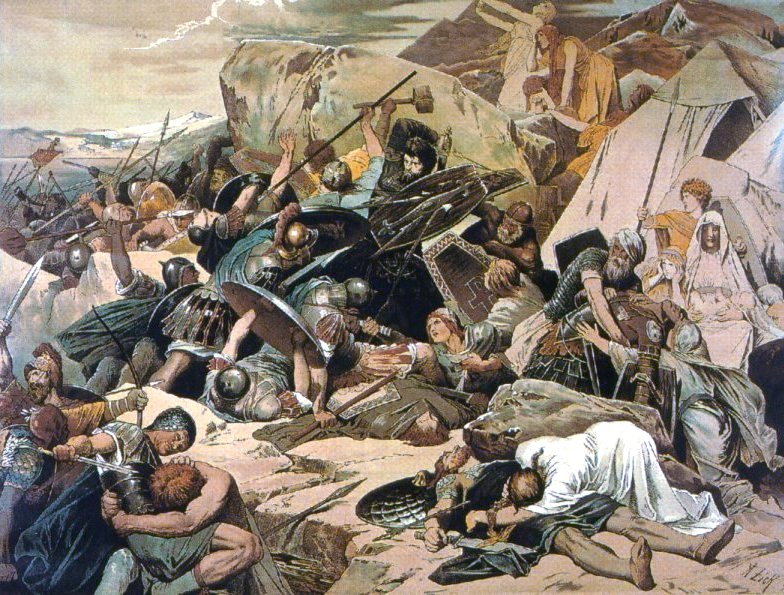

In June 533, a fleet of 500 transport ships and 92 warships were brought to the sea by order of Emperor Justinian carrying 15,000 to 20,000 combatants on board. Huns were also part of them. The patriarch of Constantinople, Epiphanius, had impregnated in the same port the blessing of heaven for a company so pleasing to God. He blessed the troops himself and pronounced ‘the habitual prayers’ (Procopius) of the farewells. The general in chief was Belisarius, a good Catholic, a good soldier, ‘a gentlemanly Christian, in whom the teachings of his Saviour had penetrated not only in his head, but in his blood’ (Thiess). […] The troops disembarked at the beginning of September of 533, two hundred kilometres south of Carthage. […]

After the victory, most of the Vandal men lost their lives. Women and children were made slaves. The [Germanic] king was taken to [the mud capital] Constantinople and presented in the summer of 534 at the racecourse during the triumph held there. Stripped of the purple he had to kiss the dust before the imperial throne. He ended his days as a vassal in a large property in Galatia. The king declined the conversion to Catholicism, despite all the honours that made it more appetising. His captive companions were framed in the Roman army and went mostly to the Persian border. Five regiments were formed, the so-called Vandali justiniani. One regiment, however, fled back to Africa after reducing the crew of the ship that was to transport them from the island of Lesbos. […]

The pope congratulated the emperor for his zeal in the expansion of the Kingdom of God. In spite of all the throat-cutting, Arianism was still far from its eradication in Africa, much less since it could penetrate the troops of Belisarius thanks to the Arian Goths. But also they (who were deceived in the distribution of the lots of lands and subjugated from the religious point of view, together with the surviving Arian vandals) had to bite the dust after hard and long struggles. Even the Vandal women who had married them were deported. ‘Of the Vandals, what remained in their homeland’, writes Procopius, ‘there remained no trace of my time. Being few, they were crushed by the border barbarians or voluntarily mixed with them so that they disappeared to their very name’. ‘In this way’, the archbishop Isidore of Seville writes triumphantly, ‘it was exterminated, in 534, the Vandal kingdom until the last sprout, a kingdom that lasted 113 years from Gunderic until the fall of Gelimer’.

But the times that took control of Africa, also in its political and religious aspect, were everything but peace. The Byzantine administration was largely corrupted, the fiscal oppression was such that the population sadly longed for the liberality of the Vandals. The settlers were now much worse treated than under the domain of the ‘barbarians’. […]

In the meantime Vitiges had already, until March 538, a long year attacking Rome with his Goths, with rolling towers, assault scales and battering rams. Again and again he restarted his rush, and again and again the Hungarian and Moorish riders made dangerous outings. The surroundings of the city, farms, villas and sumptuous buildings were totally razed. In Rome, the most beautiful Greco-Roman creations, irreplaceable masterpieces, were demolished to kill the Goth raiders with their stones. To this were added the ravages of asphyxiating heat, hunger and epidemics. Senators paid disgusting meat sausages of dead mules with gold. A relief army from Constantinople reinforced the besieged. But 2,000 horsemen, under the command of Chief John ‘The Bloodthirsty’ (epithet of the chroniclers), were merciless in Piceno against the Gothic women and children, whose husbands and fathers stood before the walls of Rome. After almost seventy rejected assaults Vitiges withdrew in the middle of terrible losses caused by Belisarius who, with tactical and technical superiority, came on his heels and occupied almost the entire country to the plain of the Po.

In the winter of 538 to 539, when the Byzantines expelled all the Goths of Emilia and Vitiges repaired the walls of Ravenna, a severe famine ravaged the northern part of central Italy, with thousands and thousands of people succumbing. Procopius, an eyewitness, reports the death of approximately fifty thousand people in the Piceno alone and even more in the northern regions.

What people looked like and how they died is something I want to tell in more detail for having seen it with my own eyes. They were all skinny and pale because their flesh, according to the old proverb, ate itself for lack of nutrition and the gall, which because of its excessive weight now had power over all bodies, produced in them a greenish paleness. And it progressed, human bodies lost all their moods so that their skin, completely dry, resembled leather, presenting the appearance of being firmly attached to the bones. Their pale colour was blackening so that they looked like teas that had burned too much. Their faces had an expression of horror, their gaze resembled the insane who are contemplating something awful… Some among them, totally dominated by hunger, came to commit atrocities against others. In a small village in Ariminus, it seems, the only two women left devoured seventeen men. Well, the strangers who came their way used to spend the night in their homes, then they killed them while they slept and ate their flesh… Driven by hunger, many threw themselves on the grass and tried to tear it off on their knees. But in general they were too weak, and when they were totally lacking in strength they fell exhaling the last breath. Nobody buried them, because nobody was interested in burying. However, not a single bird came to the bodies, although there are many species that would devour them with pleasure, as there was nothing to bite in them. Well, as already said, all the meat was totally dried out by hunger.

Around the same time Milan was also going through a horrible hardship. Dacius, the archbishop of the city—which according to Procopius was, after Rome, the first city in the West due to its size and number of inhabitants and prosperity—, went to Rome in the third year of war, informed Belisarius about the anti-Goth uprisings throughout Liguria and the Byzantine re-conquest of the territory, urging him to occupy Milan. An occupation was carried out although it supposed to break the armistice with Vitiges in April of 535. Very soon, however, the nephew of Vitiges, Uriah, surrounded Milan with a strong army supported by 10,000 Bergonds sent by the king of Theudebert’s Francs. He wanted above all to probe the situation to his advantage. From there, little by little, the famine ravaged the city frightfully. The inhabitants eat dogs, rats and human corpses. At the end of March 539 the Roman garrison capitulated obtaining a security retreat.

As far as the city is concerned, Procopius writes, ‘the Goths left no stone upon stone. They killed all men, from teenagers to the elderly in a number not less than three hundred thousand. They turned women into slaves and gave them to the Bergonds as a reward for their alliance. J.B. Bury describes the Milan massacre as one of the worst in the long series of premeditated atrocities in the annals of mankind: ‘Attila’s life path does not register such an abominable war action’. All the churches were also destroyed: the Catholic churches at the hands of the Arian Vandals; the Arian churches at the hands of the Bergond Catholics. A truly progressive ecumenical cooperation: they call it a history of redemption… The personalities of the high social hierarchy, including the prefect, brother of the pope, were torn to serve as food for the dogs. Bishop Dacius, the real cause of that hell, had set foot in dusty time.

As soon as the Bergonds returned to their land, well loaded with loot, Theudebert himself fell on Liguria, in the spring of 539, at the head of an army. Already at the beginning of the conflict, Justinian had summoned the Franks to the ‘great fight against the Goths’, as the Catholic Daniel-Rops says in the 20th century. […]

But when it seemed to him that the Goths were getting too strong he fell on them in the back, in the spring of 539, with some 100,000 francs that crossed the Alps from the south of Gaul. He devastated with his hosts Liguria and Emilia and when crossing the Po, Procopius writes, ‘they tore apart how many Goth children and women on whom they could put their hands on, and as an offering they threw their bodies into the river as first fruits of war’. The Goth warriors fled like an exhalation to Ravenna to ran into Roman swords. However, hunger and epidemics decimated Theudebert’s army in such a way that he had to leave Italy after losing a good part of it. Surrounded by sea and land, Ravenna fell in May 540 by the work of a traitor. This one burned at the request of Belisarius the barns of the city so that Vitiges had to surrender. […]

Rome itself, from which the entire Arian clergy is expelled, and in which an atrocious hunger reigns, falls twice in 546 and 550. All the walls of the squares are demolished so that no enemy can get on it and that their inhabitants will be forever free from the torture of the siege. The Romans themselves recognise after the fall of the city in 546 that Totila lived among them as a father with his children. Even the Byzantine soldiers themselves, whose pay had been subtracted, are passed on to him, and, in greater numbers still, the tenant peasants are expelled from their lands. All this enabled the hatred of the great landowners, the Catholic Church, which, like it once did in Africa with the Vandals, now spreads frightening stories about the cruelty of the Goths. […]

The year 552, in a decisive battle next to Busta Gallorum, in the vicinity of Taginae, Via Flaminia, north of Spoleto, with the support of by 3,000 Heruli and 5,500 Lombards the Goth army is completely destroyed. King Totila is killed in the flight and also the victors show off his head by shaking it at the tip of a spear. And in October of 553 the last Goth king, Teia, also falls with his army’s core after a desperate sixty-day fight at the foot of Vesuvius. And in 554, in Volturnus, next to Capua, Narses liquidates in a bloodthirsty battle other considerable troops of Franks and Alemannen who wanted to take advantage of the Goth debacle by conquering Italy. They were stabbed like cattle. The rest must have died in the waters of the river. It is assumed that only five men of seventy thousand returned alive. The castrated Narses, received by the clergy with songs of glory in the stands of St. Peter, knelt to pray on the supposed tomb of St. Peter and urged his unbridled soldiery to cultivate piety and the continued exercise of weapons. The last Goth stronghold resisted in the Apennines until 555. In the north it was not possible to take Verona and Brescia until 562 (with Merovingian help). From now in Ravenna would reside an imperial governor. The Ostrogoths would disappear from history too.

In the final phase of his extermination, Justinian took advantage of a dynastic complaint in the Visigothic kingdom to initiate a new invasion with troops led by the patrician Liberius, militarily inexperienced and more than octogenarian. In Spain, where the powerful and rich Catholic bishops reluctantly admitted their subordination to the ‘heretics’, the noble Athanagild had risen against King Agila. And as in Africa and Italy, Catholics now welcomed the intervention of the Catholic sovereign, which began a war between Byzantium and the Visigoths, a war that would last more than seventy years. In any case, Justinian did not achieve total extermination here, but his weak contingent managed to conquer the Balearic Islands, and the main port cities and strongholds in the southeast of the country.

Cui bono? The great beneficiary of all that hell: The Roman Church

The Gothic wars, with their twenty years of duration, turned Italy into a smoking ruin, a desert. According to L. M. Hartmann, who is still probably the foremost German connoisseur of that time, the injuries caused by that conflict to the country were worse than those suffered by Germany in the Thirty Years’ War. The blood tribute presumably rises to millions of victims. Entire shires were depopulated, almost all cities suffered one or more sieges and their inhabitants were more than once killed in their entirety. Many women and children were captured as slaves by the Byzantines and the men on both sides died at the edge of the sword as enemies and ‘heretics’. Rome, the millionaire city, conquered and devastated five times, ravaged by the sword, hunger and plague, had only 40,000 inhabitants. The big cities of Milan and Naples became depopulated.

Concurrently with depopulation, a horrific impoverishment spread everywhere, caused mainly by the desertification of the fields but also by the frequent slaughter of the herds. Aqueducts and damaged hot springs fell into total abandonment. Many works of art and culture of unrecoverable value were ruined. Everywhere could be seen the same spectacle of corpses and ruins, of epidemics and famines that caused the death of hundreds of thousands. Only in the Piceno region, writes Procopius, an eyewitness, about fifty thousand people died of hunger in a single year, in 539, whose bodies were so dry that not even the vultures themselves deigned to approach them. The ‘good hope’ of the emperor had been fulfilled, that ‘God, well in his grace, may grant that we recover again what the ancient Romans possessed of their borders of both oceans and lost because of later neglect’. In the year 534 Justinian could give himself the ostentatious nicknames of ‘Victor of the Vandals’ and ‘Conqueror of the Goths’.

Even the Jesuit Hartmann Grisar acknowledges that ‘what the Byzantines established in substitution of the Gothic regime was not freedom but the image of it in negative […] that amounted to subjugate the free development of personality, a system of servitude’, while ‘among the Goths authentic freedom had its own homeland there’. […]

The Arian ‘heresy’ was eradicated from Africa. Italy also disappeared as an independent kingdom while, in that general chaos, the ‘State of the Church’ was growing as an immense parasite. The ancient privileges of Rome were restored and Justinian increased the power and prestige of the Roman bishop. […]

The one especially benefited by the war was the Ravenna church, whose regular income was estimated at that time at some twelve thousand solidi (pieces of gold). Its territorial possessions, that reached Sicily, continuously increased through the donations and the inheritance legation. Wealthy bankers built and equipped many, let’s call them, houses of God. But, above all, the Bishop of Ravenna benefited especially from the appropriation of the churches and Arian goods whose number was particularly increased in the surroundings of the ancient Goth capital. […]

But while it is true that the emperor did not precisely wage his wars, lasting more than twenty years ‘for the freedom of the subjects’, he did it for the ‘right faith’. For the sake of this, as it is firmly stated, he had sacrificed and erased two peoples from the Earth. For the recuperatio imperii, so amazing for many contemporaries and for Justinian himself, consisted essentially of the bloody re-conquest of northern Africa and Italy in favour of Catholicism. The despot thus became ‘champion of the Roman Church’ (Rubin). […]

The chronicler of the time, Procopius, a model of Byzantine historiography, incessantly accuses the emperor of murder and robbery of his subjects. Procopius’s accusations culminate in the 18th chapter, which presumably adheres to the truth essentially in spite of some exaggerations, especially as regards the figures, or when using hyperbole like this: ‘It would be easier to count all the grains of sand than the victims sacrificed by this emperor’.

Of Libya, of such extensive dimensions, he plunged it into such a ruin that even a long walk would hardly give one the surprise of meeting a person. And if there were at first 80,000 vandals in arms, who could estimate the number of women, children and servants? How could anyone enumerate the multitude of all Libyans (Romans) who previously lived in cities or engaged in agriculture, navigation or fishing as I myself could see far and wide with my own eyes? And all of the Numidia population, even more numerous, perished with women and children. And finally the land housed many Roman soldiers and their companions of Byzantium. So whoever indicated for Africa the figure of five million dead would fall somewhat short of reality [emphasis by Ed.].

Italy, at least three times larger than (the province of) Africa, is, in large regions, even more depopulated than this one so that it will not be very difficult to guess the number of those who perished there. […] Before that war, Gothic power extended from Gaul to the borders of Dacia, where the city of Sirmium is located. The Germans (the Franks!) seized many territories in Gaul and Venice, when the Roman army arrived in Italy. Sirmium and its surroundings were occupied by the Gepids, but everything, said briefly, is now depopulated. […]

Such were, therefore, the consequences of the war in Africa and Europe.

When the tyrant died the people were not free and the Empire was economically exhausted, on the verge of bankruptcy. For the papacy, on the other hand, the Justinian era—due to the re-conquest, the extermination of two powerful Arian towns, and the dissolution of the autonomous kingdom of Italy—proved to be extremely advantageous in material and legal terms.