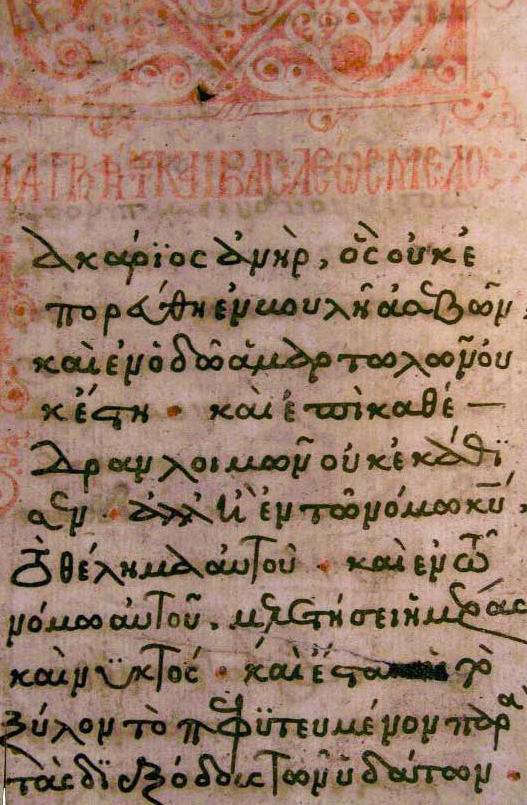

Below, part of Gospel Fictions’ second chapter, “How to begin a Gospel” by Randel Helms (ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages):

A central working hypothesis of this book and one of the most widely held findings in modern New Testament study is that Mark was the first canonical Gospel to be composed and that the authors of Matthew and Luke (and possibly John) used Mark’s Gospel as a written source. As B.H. Streeter has said of this view of Mark:

Its full force can only be realized by one who will take the trouble to go carefully through the immense mass of details which Sir John Hawkins has collected, analyzed, and tabulated (pp. 114-153 of his classic Horae Synopticae). How anyone who has worked through those pages with a synopsis of the Greek text can retain the slightest doubt of the original and primitive character of Mark, I am unable to comprehend… The facts seem only explicable on the theory that each author had before him the Marcan material already embodied in a single document.

When the author of Mark set about writing his Gospel, circa 70 A.D., he did not have to work in an intellectual or literary vacuum. The concept of mythical biography was basic to the thought-process of his world, both Jewish and Graeco-Roman, with an outline and a vocabulary already universally accepted: a heavenly figure becomes incarnate as a man and the son of a deity, enters the world to perform saving acts, and then returns to heaven. In Greek, the lingua franca of the Mediterranean world, such a figure was called a “savior” (soter), and the statement of his coming was called “gospel” or “good news” (euangelion). For example, a few years before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, the Provincial Assembly of Asia Minor passed a resolution in honor of Caesar Augustus:

…in giving to us Augustus Caesar, whom it [Providence] filled with virtue [arete] for the welfare of mankind, and who, being sent to us and to our descendents as a savior [soter]… and whereas, finally that the birthday of the God (viz, Caesar Augustus) has been for the whole world the beginning of the gospel [euangelion] concerning him, therefore, let all reckon a new era beginning from the date of his birth.

A few years earlier, Horace wrote an ode in honor of the same Caesar Augustus which presents him as an incarnation of the god Mercury and outlines the typical pattern of mythical biography: Descent as a son of a god appointed by the chief deity [Jupiter] to become incarnate as a man, atonement, restoration of sovereignty, ascension to heaven—a gospel indeed, and so the pattern of the Christian Gospels!

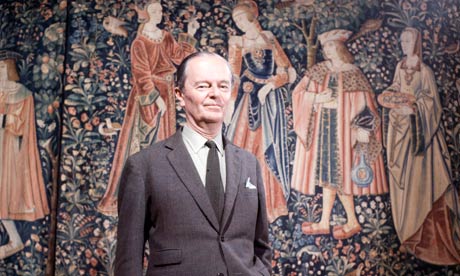

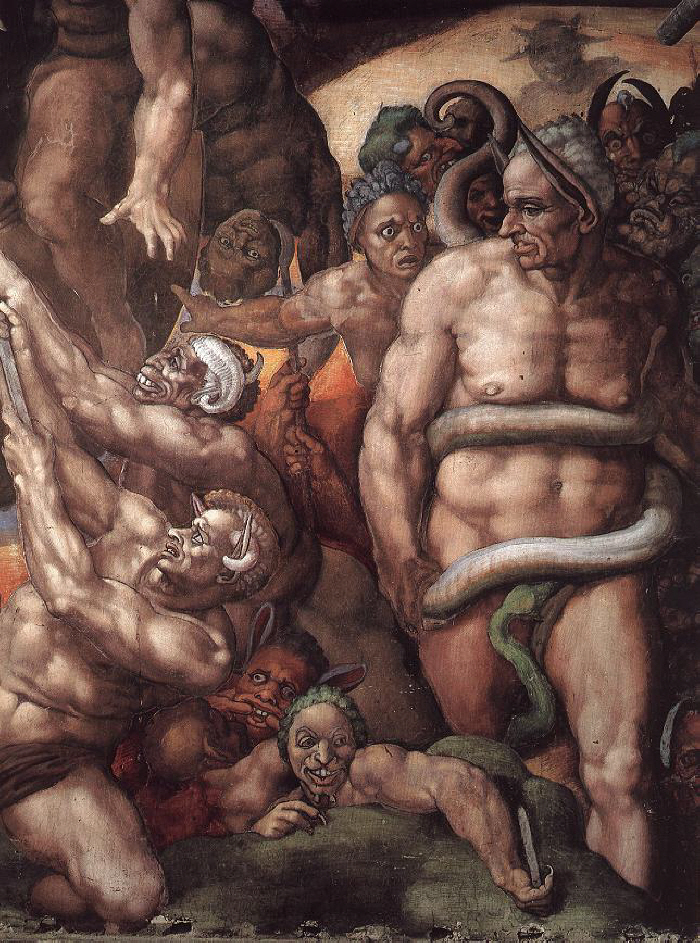

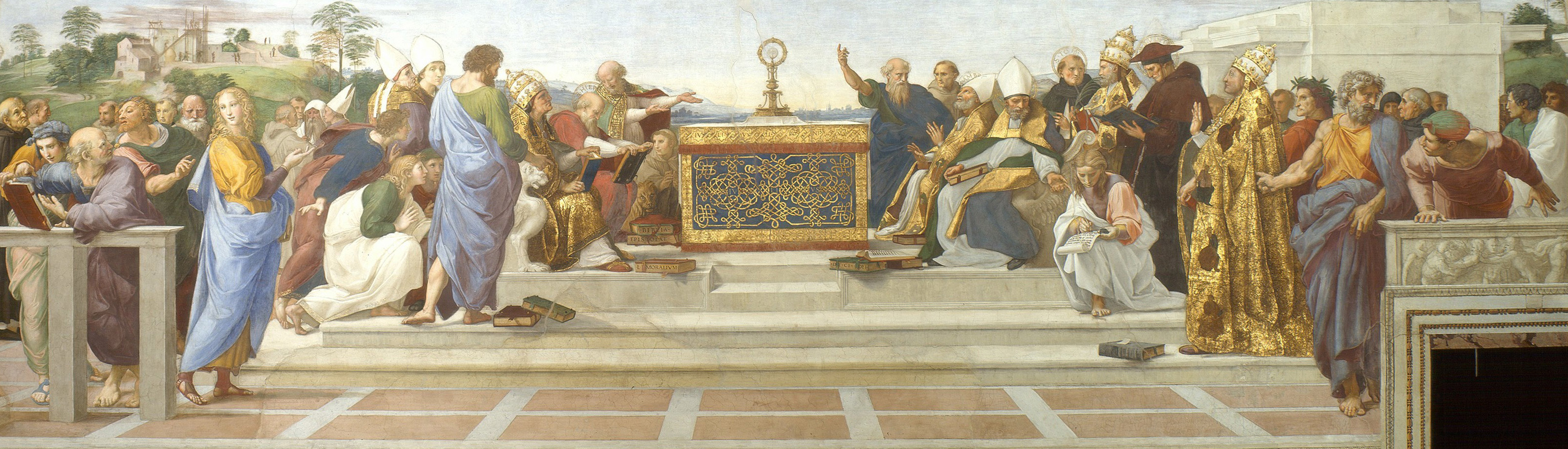

(The divine emperor. When a Roman emperor died he was traditionally regarded as having become god. Here Claudius, in life a timid man with a stutter and a limp, has been transformed into Jupiter, Vatican Museum, Rome.)

(The divine emperor. When a Roman emperor died he was traditionally regarded as having become god. Here Claudius, in life a timid man with a stutter and a limp, has been transformed into Jupiter, Vatican Museum, Rome.)

The standard phrase “the beginning of the gospel” (arche tou euangeliu) of Caesar (or whomever) seems to have been widespread in the Greco-Roman world. A stone from the marketplace of Priene in Asia Minor reads: “The birthday of the god (Augustus) was for the world the beginning of euangelion because of him.” Mark uses the same formula to open his book: “The beginning of the gospel (arche tou euangeliu) of Jesus Christ the son of God [theou hyios].” Even the Greek phrase “son of god” was commonly used for Augustus. On a marble pedestal from Pergamum is craved: “The Emperor Caesar, son of God [theou hyios], god Augustus.” Mark begins his mythical biography of Jesus with ready-made language and concepts, intending perhaps a challenge: euangelion is not of Caesar but of Christ!

The early Christians could have found out what we would call historical information about Jesus, but in fact they did not. Neither Mark nor anyone else in the Christian community (perhaps circa 70 A.D. Rome) had been in Palestine at the time; all the participants were now dead, and Mark had a book to write.

Certainly, there lived a Jesus of Nazareth, who was baptized in the Jordan by John, who taught, in imitation of John, that “the kingdom of God is upon you” (Mark, 1:15); and who was killed by the Romans as a potentially dangerous fomentor of revolution. Of the outline of Jesus’ life itself, this is just about all that Mark knew. Mark possessed a good many fictional (and some non-fictional) stories about Jesus and a small stock of sayings attributed to him, and he incorporated them in his Gospel; but he had no idea of their chronological order beyond the reasonable surmise that the baptism came at the beginning of the ministry and the crucifixion at the end. Mark is, in other words, not a biography; its outline of Jesus’ career is fictional and the sequence has thematic and theological significance only. As Norman Perrin bluntly puts it, “The outline of the Gospel of Mark has no historical value.”

Mark certainly knew what to put first: “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1). But Mark’s beginning comes when Jesus is already a grown man only a few months away from death. His Gospel says nothing about Jesus’ birth or childhood, has almost no meaningful chronology, presents very little of Jesus’ moral teaching (no Sermon of the Mount, no parables of the Prodigal Son or Good Samaritan), and has a spectacularly disappointed ending: the Resurrection, announced only by a youth, is witnessed by no one, and the women who were told about it “say nothing to anybody, for they were afraid” (Mark 16:8). End of Gospel.

Mark wrote some forty years after the Crucifixion, when Jesus was already rapidly becoming a figure of legend. John the Baptist presented genuine problems. Since the baptism made John look like the mentor of Jesus and the initiator of his career, the Baptist had to be demoted, but not too much; the initiator became the forerunner. Mark’s method of performing that demotion is fascinating because, paradoxically, it does in fact the opposite, and had to be corrected, three different ways, by the other three evangelists.

The baptism itself was the first awkward fact. Ordinarily, John’s baptism stood as a sign that one had repented of sin: “A baptism in token of repentance, for the forgiveness of sins” (Mark 1:4). It appears not to have troubled Mark that he presented Jesus as a repentant sinner. There is no hint in Mark’s first chapter that Jesus was in any way the Son of God before his baptism; indeed, there is the clear hint that at least Mark’s source, if not Mark himself, held the “adoptionist” theology.

(Jesus’ baptism by John the Baptist, from a fifth century mosaic in Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Ravenna. Note Jesus’ nudity and his youthful, beardless face.)

(Jesus’ baptism by John the Baptist, from a fifth century mosaic in Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Ravenna. Note Jesus’ nudity and his youthful, beardless face.)

All things considered, Mark does not begin his story of Jesus very satisfactorily. Indeed, within two or three decades of Mark’s completion, there were at least two, and perhaps three, different writers (or Christian groups) who felt the need to produce an expanded and corrected version. Viewed from their perspective, the Gospel of Mark has some major shortcomings: It contains no birth narrative, it implies that Jesus, a repentant sinner, became the Son of God only at his baptism; it recounts no resurrection appearances; and it ends with the very unsatisfactory notion that the women who found the Empty Tomb were too afraid to speak to anyone about it.

Moreover, Mark includes very little of Jesus’ teachings; worse yet (from Matthew’s point of view), he even misunderstood totally the purpose of Jesus’ use of parables [see below]. Indeed, by the last two decades of the first century, Mark’s theology seemed already old-fashioned and even slightly suggestive of heresy. So, working apparently without knowledge of each other, within perhaps twenty or thirty years after Mark, two authors (or Christian groups), now known to us as “Mathew” and “Luke” (and even a third, in the view of some—“John”) set about rewriting and correcting the first unsatisfactory Gospel. In their respective treatments of the baptism one obtains a good sense of their methods.

Mark had used his source uncritically, not bothering to check its scriptural accuracy. But Mathew used his source—the Gospel of Mark—with a close critical eye, almost always checking its references to the Old Testament and changing them when necessary, in this case dropping the verse from Malachi wrongly attributed to Isaiah and keeping only what was truly Isaianic. [Mark writes as if he quotes Isaiah 40:3 but his verse is a misquotation of Malachi 3:1]

Mathew disliked Mark’s perhaps careless implication that Jesus was just another repentant sinner, so he carefully tones it down, inventing a little dramatic scene. When Jesus

came to John to be baptized by him, John tried to dissuade him. “Do you come to me?” he said. “I need rather to be baptized by you.” Jesus replied, “Let it be so for the present; it is suitable to conform in this way all that God requires.” John then allowed him come. (Matt. 3:13-15)

This scene is found in no other Gospel and indeed contains two words (diekoluen, “dissuade”; prepon, “suitable”) found nowhere else in the New Testament. The verses are Matthew’s own composition, created to deal with his unease at Mark’s implication about the reason Jesus was baptized—not as a repentant sinner but to fulfill a divine requirement. Why God should require Jesus to be baptized, Mathew does not say.

Like Mathew, Luke was also unhappy with Mark’s account of the baptism and made, in his own way, similar changes. The Fourth Gospel takes an extreme way of dealing with the embarrassment of Jesus’ baptism by John: you will find there no statement that Jesus ever was baptized.

Developing theology creates fictions. Moreover, each gospel implicitly argues the fictitiousness of the others. As Joseph Hoffman has put it, “Every gospel is tendentious in relation to any other.” This is especially true with regard to Mark and the Gospels—Mathew and Luke in particular—intended to render Mark obsolete. The fictionalizing of Mark is one of the implicit purposes of the First and Third Gospels, whose writers used what were probably, in their communities, rare or even unique copies of Mark and who clearly expected that no more would be heard of Mark after their own Gospels were circulated. We do an injustice, Hoffman notes, “to the integrity of the Gospels when we imagine that these four ever intended to move into the same neighborhood.”

This becomes quite clear, for example, in two synoptic scenes describing Jesus’ telling the parable of the sower and the seed:

When he was alone, the Twelve and others who were round him questioned him about the parables. He replied, “To you the secret of the kingdom of God has been given; but to those who are outside, everything comes by way of parables, so that (as Scripture says) they may look and look, but see nothing. They may hear and hear, but understand nothing; otherwise they might turn to God and be forgiven.” (Mark 4:10-12)

It is not difficult to imagine Mathew reading this passage, scratching his head, and wondering how Mark could so totally misunderstood the purpose of a parable—a small story intended to illuminate an idea, not obscure it. But Mark was a gentile, living perhaps in Rome; and though he clearly knew little of the tradition of Jewish rabbinic parabolic teaching, he was familiar with Greek allegorical writing, which was often used to present esoteric ideas in mystifying form. Mathew, on the other hand, was a Hellenistic Jewish Christian who knew perfectly well that a rabbi’s parables were intended to elucidate, not obfuscate. Yet, here was Mark clearly insisting that Jesus’ parables were meant to prevent people’s understanding his message or being forgiven by God: a passage, moreover, that cites Scripture to prove its point.

We can imagine Mathew’s relief when he checked the reference in the Old Testament and found that Mark had got it wrong. Actually, Mark’s citation of Isa. 6:9-10 agrees with the Aramaic version rather than with the Septuagint, but Mathew went to the latter for his quotation, which allowed him completely to change the point of Jesus’ statement. Jesus speaks in parables to enhance people’s understanding, insists Mathew, not to prevent it. That Mark’s account of the scene is simply wrong is Mathew’s implication [see Matt. 13:10-15].

Mathew and Luke found that one way of dealing with the Sonship question lay in the nativity legends already circulating about Jesus: he was the Son of God because God impregnated his mother. Both Mathew and Luke added birth narratives to their revisions of Mark, basing them on legends quite irreconcilable with each other. The next chapter examines these nativity legends.