of The West’s Darkest Hour

I have wanted to settle the score with them for years because they are a microcosm of what happens on the extreme wing of racial dissent. What I wrote in my previous post about one of them, who told me he was going to commit suicide, released my reticence. Now I am ready to say to them a few truths.

I apologise in advance if, regarding the twenty-five commenters I have chosen below as a paradigm, many other regular commenters from the past or present don’t appear. For example, Adit has commented here numerous times, but only those who have made me think of something I would like to respond, appear in the list below. And the same can be said for many other commenters who do not appear below.

Likewise, I won’t offer my views on the commenters from the first incarnation of The West’s Darkest Hour that ran from 2009 to 2011 (the second incarnation was deplatformed by WordPress; the current one is the third). Since I started my blogging career in the counter-Jihad, in that first incarnation there were still commenters who came from those quarters, including notable Jews like Larry Auster and Takuan Seiyo. In that old incarnation of this site I passed the mic to a critic of this pair, Tanstaafl, who also doesn’t appear in the twenty-five commenters below. Nor do notable racialists like Matt Parrott appear because he barely commented on this site.

So here we go! The commenters I chose are listed in alphabetical order:

Arch Stanton

This good man is one of those white nationalists who sees everything through the prism of the Jewish question. I found it so maddening to argue with him that after a few years I told him he was no longer welcome. There are quite a few commenters like this Christian on the American racial right. I remember one of my articles where I was talking about pre-Hispanic Amerindians and… Arch Stanton jumped in to talk about Jewry. Those were times when there wasn’t a single Jew on the American continent. But these monocausalists sometimes cannot bear to see anything outside their Judeo-reductionist prism.

Adunai

I banned this Ukrainian (or ‘little Russian’ as he once called himself) several times for bad behaviour; I let him comment again and again over a few years, and eventually I banned him permanently. I spared him before because Adunai has a good grasp of what the transvaluation of values is. But his admiration for Stalin means that his comments had no place on a site that honours the memory of Adolf Hitler and the German people of the previous century. A few examples will exemplify why I banned him.

A couple of times he said that it might be a good idea for parents to burn their children alive in the context of ritual human sacrifice (cf. my book Day of Wrath).

Over the years I have kept diaries in which I write my views about my soliloquies, my family and even the commenters, sometimes writing long entries saying very harsh things. When I attracted people to my site who dared to make such comments, on June 19, 2019, I wrote: ‘What am I doing wrong? What did [George Lincoln] Rockwell do wrong by accepting into his ranks the one who would kill him?’ (my Diary #20, page 120). And on the next page we can read a paragraph that portrays me:

Just as Alcides and Rafael [chess comrades] came a few years ago to eat meat on my birthday and I had a vegetarian dinner, the following year, now more refined, I didn’t even invite them (they still eat meat and I didn’t want to see them at my table doing that again). In the same way I cut off the defective ones who come to my blog. It doesn’t matter that I’m left alone. What matters is both my physical and companionable diet.

Two pages further on we can read in my diary from five years ago: ‘It is time for a true priest of the 4 and 14 words to be born’.

Adunai could not understand why, if I was an exterminationist, I wasn’t at the same time cruel to animals. The answer is simple: if I am an exterminationist it is precisely because humans are cruel to animals (and many to their own children, as is clear from my trilogy in Spanish).

By the way, Adunai still lives in Ukraine. He is lucky he hasn’t been conscripted to fight against the Russians, though I ignore the details of his life in the ongoing war.

Autisticus Spasticus

I also had to ban this young Brit because, as his pen name suggests, he is kind of autistic. Over a few years he asked, or rather demanded, that I give him my opinion on a matter that was of utmost importance to him (something related to artistic representations of women in Greco-Roman times). He never seemed to understand that I wasn’t obliged to answer all his questions. His mental condition makes him believe that he is entitled to have us answer off-topic questions in discussion threads (he recently did it to me again in The Unz Review; obviously I didn’t answer him).

And by the way, I ask those I have banned not to bother trying to comment below. I’ll archive your opinions, yes: but I won’t let them through here.

Axl Atman

This woman used to comment here a few years ago. Her comments were intelligent, except for her intellectual sympathies for Satanism. These sympathies for the devil and Charles Manson are a very typical American pathology (though sometimes Europeans become infected with it too). I will address this issue later when talking about other commenters. I never banned Atman, but she stopped commenting after a debate we had on Greco-Roman pederasty.

Benjamin

I talked about him on Friday in the post revealing that he was committed this month to an insane asylum. Despite not being rich, Benjamin has been a generous sponsor of this site. On my anti-psychiatric site in Spanish I have written about how we should treat an individual suffering a psychotic crisis: in a humane way and under no circumstances resort to involuntary psychiatry (those who don’t speak Spanish can translate my article with Google).

Dr Morales

This Latin American used to comment on this site. I wrote last month about this troll who impersonates me on racialist forums, saying incredibly stupid things under my name to discredit me in the eyes of my colleagues. Here I would just like to add that, remedying my prose, the impersonator Morales has recently been using my initials in his pen name for The Unz Review: ‘C.T. Priest of the fourteen words’.

Gaedhal

This Irish’s linguistic exegesis of the Bible and critique of Christianity is very erudite. Alas, as in my case and despite our anti-Christianity, there are still many religious introjects lingering in the depths of our unconscious—introjects that neither Gaedhal nor I have been able to exorcise. Such is the power of the parental introject…! After writing my autobiographical trilogy of almost two thousand pages, I realised that removing all the programming implanted in us by our (abusive) parents is a task for gods rather than mortals.

Highrpm

This man, whose initials are R.M. and who years ago commented here copiously, is the only one of the commenters whom I quote in one of the epigraphs of my trilogy. For the sake of modesty, I wouldn’t like to cite that quote (although it is no secret for those who obtain a copy of the book). I will always remember his laudatory words.

Iranian for Aryans

I don’t know if I behaved badly with this Iranian but I would like to ask for an opinion on the matter.

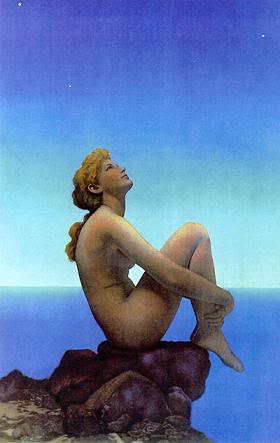

Since the beginning of the second incarnation of this site in 2011, this man, who also commented on other forums (e.g. Counter-Currents), said things about degenerate music that no Aryan said in those forums. They all seemed degenerate in musical tastes compared to this US-based Iranian’s fondness for classical music. He even sent me an illustrated book about Maxfield Parrish which was impossible to order from Mexico via Amazon Books.

But on Facebook I discovered that he had a blonde girlfriend… This is neither the fault of the Iranian nor of the blonde: it is the fault of the Aryan men of that country and of the West in general who allow the existence of such couples (cf. what I will say below about the Visigoths). I scolded him by email and he informed me that he had no offspring with this woman, and it seems that he already has separated from her.

My dilemma in judging him is that, while he defends the West in matters of music and cultural degeneracy in general, he shouldn’t have posted those photos on Facebook. If he were really an Iranian fighting for Aryan interests, he should make it clear that only by adopting a hundred per cent Nordid child, and never having offspring of his own, would it be legitimate to have such a partner to raise him or her.

Irrelevant Nobody

It was this Greek, who told me on Friday that he was going to commit suicide, who motivated me to write this article.

What can I say?

First of all, if he did commit suicide his eulogy of Hitler and Himmler is at odds with such a decision (if he ever followed through on it).

I am forty years older than this Greek, and yet I would like to adopt an Aryan baby to raise him with a female friend I have known for thirty years. If what Irrelevant Nobody says is true, he gives no details of his family tragedy. My family also suffered such a horrible tragedy that drove my now-deceased sister mad. And yet I follow the motto of Martin Kerr about a genuine National Socialist: National Socialism is a lifestyle. This means, as Savitri Devi rightly saw, taking our vows in what she called ‘the religion of the strong’. And that in turn means that despite rain, thunder or lightning, in our lives we must always work to fulfil the ideals of the Führer.

I told the Greek young man in two emails that, if he committed suicide, the System would win. That is precisely what the System wants us dissidents to do!

If what he told me in his email is true and he is now dead, I must say that there is no right to kill oneself if it is possible to do something for the sacred words. And the most painful thing is that this Greek lad was, if I give credence to his comments posted on this site, almost an ideological clone of me at the level of a pupil: something truly impressive.

If anyone lives in Greece, please research the name of this man mentioned in the previous post along with his day of birth (and death?). I would be very interested to know if what he told me is true.

Jack Halliday

This lad was one of the most intelligent commenters on this site. But he got really mad when, in a thread, I said that Charles Manson fans had a screw loose, which I still believe. I called him a ‘teenager’, which is not an insult as Halliday was a teenager during that flaming debate, and after calling me mudblood and countless other insults by email he never commented again.

This is another facet of the West’s dark hour. In my day teenagers respected adults, especially those who were decades older than them, as in my case compared to Halliday (to whom, by the way, I had sent Day of Wrath to England, although we never met in person). Now the kids feel entitled to insult the elders. It is obvious that, despite his intelligence—thanks to Halliday I discovered the essay of Judea against Rome in Evropa Soberana—it is good that we have made a clean break. (Incidentally, a Spanish-language Metapedia editor has just published an article about this webzine that the System banished.)

In my diaries I wrote many entries on commenters that disappointed me, as my January 2019 entry shows. Halliday, who apparently suffered bullying, adored the killers of their schoolmates (consider the bullying that the kid who attempted on Trump’s life had experienced at school!). Halliday and I live in different universes. He once compared Charles Manson and Adolf Hitler to the detriment of the latter and criticised Adolf for going to the opera. Echoing the writings of James Mason, Halliday claimed that salvation comes from the lowest strata of society, and morbidly linked videos of perpetrators like those of the Columbine massacre.

In the flaming discussion thread I rephrased a saying to Halliday: ‘Tell me who you admire and I’ll tell you who you are!’

Jake F.

To Jake I originally dedicated the first editions of my Day of Wrath. He was the first commenter who started providing me with very positive feedback on my articles that revalued values, such as ‘Dies Irae’ published in 2011. In 2016 he even interviewed me. Not long ago Jake stopped commenting here for unknown reasons. I conjecture that my criticism of the US (cf., for example, what I said on July 11 about George Washington) is related to his distancing himself from my site. Note from July 28: In the comments section, Jake has clarified that he has not distanced himself from our POV.

Jamie

When Jamie started commenting here there was still a residue of Christian morality in his mindset, but it didn’t take him long to understand our point of view. I don’t know much about his personal life but, from what he comments, I guess he’s been in the racialist movement for a while now, and knows it much better than I do (I only discovered it in my early fifties!).

John Martinez

I have already talked about this Brazilian in the post where I confessed that he stood me up, for almost an hour, in a London underground station the day I arrived in London from the other side of the Atlantic, without sleeping on the journey, and without telling me he had gone to drink beers (or to find a toilet to urinate the residue of the beers he had ingested)!

I don’t want to add anything more here about that embarrassing day. But what happened to me was the result of admiring a guy’s intellect without gauging his character. Like Halliday, Martinez had a high IQ. But in both cases I failed horribly, judging them solely on their intellect. When I went back and told my friend about it, she remarked that this was a typical male mistake. She was right: a good character is infinitely more relevant than mere IQ.

Joseph Walsh

Like Martinez, I dealt with Walsh during that trip to the UK. Walsh is now serving a seven-year prison sentence. He was charged with terrorism for what he said on the podcasts with his friend Chris Gibbons, who is also serving a similar sentence, but as far as I know neither was inciting violence (see my article here). I wasn’t at the trial but I’d love to hear from someone with more knowledge of exactly what happened earlier this year in that trial. Along with Benjamin who has been committed to a psychiatric ward, two former commenters on this list are now locked up by the System.

But Walsh always had a dark side: his admiration for Charles Manson. Before prison, he had already been committed because of abuse inflicted on him as a teenager by his mother (a good reader of Alice Miller who, years later, would apologise to her son). When I lived in Walsh’s flat for a few days a decade ago, I showed him a video of Robert Whitaker, a critic of the iatrogenic psychiatric drugs Walsh was taking. He ignored me and preferred to continue admiring Manson rather than the critics of the pseudoscience that had him suffering from akathisia that I myself witnessed in his flat.

I never banned Walsh from commenting here. But already by 2019 I liked that he was hardly commenting as he used to do before. The case of a Romanian I will discuss later will add to my thoughts on Halliday and Walsh.

Kurt

Above I was asking if I misbehaved with the Iranian, in as much as I told him off strongly when I saw the photos with his partner. But in Kurt’s case, I do think I behaved badly towards him.

A few years ago, in response to comments he made trying to understand homosexual behaviour, I told him he was homo and didn’t apologise for it. I rarely regret the harsh things I have said in the comments section but I do harbour some regrets in this case (Kurt hasn’t commented here again, understandably).

Mauricio

I can’t comment on him for obvious reasons (next month we’ll meet in person, and only then we’ll discuss our differences).

Mister Deutsch

Of Italian descent, this was one of the first commenters on the second incarnation of this site. He was offended when I pointed out that a brown-skinned Italian football player wasn’t white. He stopped commenting.

Like Halliday and Martinez, what struck me about this Italian was that he was very insightful, until his blind spot came out. Years later even Jake F. remembered Mister Deutsch in one of our podcasts. It’s funny how the Mediterranean’s complex towards those who take Nordicism for granted is so deep that such an obvious thing, as pointing out skin colour, becomes taboo. They prefer to abandon discussion in order not to touch one of the silly dogmas of American white nationalism: the equality between Mediterraneans and Nordids.

Roger

This cultured Briton, like the Iranian, understood as few others do the toxicity that degenerate music represents for the spiritual health of the Aryan soul (something similar to the toxicity that pornography represents for our spiritual health). Thanks to one of his comments I understood why Solzhenitsyn, though he wanted so much to destroy Bolshevism, never endorsed Hitler’s war. Roger made me realise that it was because of Solzhenitsyn’s Orthodox Christianity: something that hadn’t occurred to me until then. Unfortunately, when I was travelling in the UK and wanted to meet Roger personally, he didn’t reply to my emails.

Rollory

More than once this young American made a sharp observation refuting one of the myths of liberal egalitarianism: that valuing human beauty is subjective. He pointed out that, by comparing the most harmonious cranial proportions with some mathematical proportions, it had been discovered the effect that beauty produces. Unfortunately, Rollory, whom I had known since my stage on the anti-jihad forums, was offended when he mailed me a book and I told him I wouldn’t read it because of the small size of its letters. He has not commented since.

Owl of Minerva

This Australian was the most generous sponsor I have ever had. But he so abruptly stopped communicating with me that I assumed he had passed away. I kept sending him Christmas cards to Australia but his family never replied. I know his real name but I don’t want to reveal it in this entry.

Spahn Ranch

I believe he is Dr Morgan who has commented on The Unz Review and who has used other pseudonyms both on my site and on The Occidental Observer.

While his views of Christianity have been spot on, he never wanted to respond honestly to the critique of his techno-reductionism that Adunai and I have made. Although, as we saw on Thursday, I am in favour of returning to the plough (mankind isn’t yet ready for technological civilisation), Ranch never answered an obvious objection.

Adunai and I believe that Christian morality is the primary cause of the white man’s ills, especially the exterminationist self-hatred of his own ethnicity. If technology were primarily responsible, highly technological nations like China would suffer from this exterminationist self-hatred. They don’t suffer from it for the simple fact that it is only former Protestant and Catholic countries that are now suffering from ethnosuicidal neochristianity. (Something akin to what Tom Sunic tried to convey in that memorable meeting in a Hungarian restaurant, with Jared Taylor present, when Richard Spencer was escorted by the police so that he wouldn’t speak.)

Along with Jack Halliday and Joseph Walsh, Ranch was one of a trio of intelligent commenters who disappointed me big time when I realised that they admired Charles Manson. Ranch even went so far as to say that it was all well and good to pick on victims like those the Manson family martyred. It was hard for me to lose three intelligent commenters on the same day. Although I didn’t ban them, it was obvious that we were living in parallel universes.

SS Division Poltergeist

This Romanian also used to post comments under another pen name on this site. Like Adunai, SS Division Poltergeist had a very good understanding of the Christian problem, to the extent that he was aware of the ideological misdirection represented by those who blame one hundred per cent of our problems on Jewry. But five years ago I expelled him for the same reasons I would expel Adunai.

That happened when I was quoting Tom Goodrich’s book, Summer 1945. Both he and Adunai said, in very strong terms, that one shouldn’t feel the slightest compassion for the German martyrs of the Second World War. The Romanian said this with such vehemence in scolding Goodrich that I expelled him for the first time (sometime earlier I had expelled Adunai for the first time for saying something identical about animals martyred by humans). In my diary I wrote: ‘It is unbelievable that these guys don’t realise that I hate them more than I hate the Jews for saying such things’.

After I let him comment again (a great weakness of mine and not only with him!), a few months later this Romanian said that Hitler had been a coward for going back on removing the crucifixes from Bavaria. This is nonsense, since every good politician has to compromise with his people regardless of his convictions. Such comments, and his blasphemies against the martyrs of WW2, moved me to ban him for good.

Stubbs

This man, who also commented on Alex Linder’s forum under the pen name Vance Stubbs, was another one of those whose intelligence impressed me. He seems to have been disappointed by something unspecific and stopped commenting (I don’t know if he continues to aggregate his opinions on other racialist forums under another pen name). To Stubbs I owe the insightful observation that white nationalists—Christians and neochristians in the final analysis!—treat Mediterraneans as Republicans treat mestizos (Stubbs was referring to the American Republican Party).

Tom Rogers

Several years ago Jack Halliday gave Tom Rogers a very wise retort. Like virtually all British men today, Rogers’ greatest character flaw lies in his utter inability to hate his country’s traitors (the antithesis of Rudyard Kipling’s poem that the English should learn to hate again!). I would like to illustrate this with an example of other Englishmen who have nothing to do with Tom Rogers.

On several occasions I have told myself, on my walks in the street, that having internet stalkers like Dr Morales is not my problem. Even the most subversive Jews are not my problem! My problem is the contemporary Aryan. Let us take into consideration what I said on Friday.

Take a look at the faces of Christian Glen Scrivener and neochristian Tom Holland. From a biological point of view, both Englishmen are perfect Aryan specimens. As I see it, just because they are Aryans, they are entitled to have a harem of English roses to impregnate copiously. But not only do they not fantasise about it. Their concern is the welfare of the ‘minorities’ that have invaded their cuck island and, like every Christian and neochristian throughout the West, that Nazism shouldn’t re-emerge!

They are my problem, not the Jews or Latin Americans who defame me over the internet. Pure Aryans infected by an ethnosuicidal ideology are my real enemies. That is, virtually all white men are my enemies in that, almost without exception, they are either Christians or neochristians. (For those unfamiliar with Holland’s book let me rephrase that statement thus: All contemporary whites are either Christians or liberals.)

There’s the rub. How can the priest of the sacred words flourish in a world that inverted the values not only of the classical world, but the values of the Indo-Aryan world, of the world of the ancient Germans and the Vikings?

I will remain faithful to the religion of the strong, to the ideals not only of Hitler but of the Indo-Aryans who didn’t want to soil their blood with the Indian natives, or the Visigoths who burned at the stake those who interbred with the mudbloods of the Iberian peninsula. I will fulfill my priesthood even if the world is upside down from the ideal that Irrelevant Nobody left in his suicide note echoing David Lane’s second fourteen words: ‘…because the beauty of the White Aryan women must not perish from the earth’.

As Holland and Scrivener rightly explained in the video linked in my Saturday post, from an axiological point of view Woke atheism and Christianity are related. If the imperial church inaugurated by Constantine hadn’t corrupted the Aryan soul, whites today wouldn’t be mad as hell with an ethnosuicidal religion that virtually everyone and anyone suffers from. This applies even to those white nationalists reluctant to distinguish, like Mister Deutsch and countless others, between white skin and brown skin—in order not to hurt the feelings of non-Nordid Caucasoids!

I live surrounded by brown mestizos. My quixotic father chose the house, where I now live with my sister, in an old area that reminded him of Spanish colonial times. There are other areas in the city whose residents are much whiter than the ones I see every day.

But that sea of brown people is not my problem. My problem is the Catholicism of my anti-racist father, now deceased, and the ideology of Aryans like Holland and Scrivener of whom there are hundreds of millions. They are my problem and they are also the problem for their offspring in that, unless they wake up, the world of the future will be as mixed race as those I see on the streets every day.