Aristotle and Greek science

Under Plato he studied eight—or twenty—years; and indeed the pervasive Platonism of Aristotle’s speculations, even of those most anti-Platonic, suggests the longer period. One would like to imagine these as very happy years: a brilliant pupil guided by an incomparable teacher, walking like Greek lovers in the gardens of philosophy. But they were both geniuses; and it is notorious that geniuses accord with one another as harmoniously as dynamite with fire. Almost half a century separated them; it was difficult for understanding to bridge the gap of years and cancel the incompatibility of souls.

On the same page Durant adds that Aristotle

was the first, after Euripides, to gather together a library; and the foundation of the principles of library classification was among his many contributions to scholarship. Therefore Plato spoke of Aristotle’s home as “the house of the reader, ” and seems to have meant the sincerest compliment; but some ancient gossip will have it that the Master intended a sly but vigorous dig at a certain book-wormishness in Aristotle.

After an unquoted paragraph Durant writes:

The other incidents of this Athenian period are still more problematical. Some biographers tell us that Aristotle founded a school of oratory to rival Isocrates; and that he had among his pupils in this school the wealthy Hermias, who was soon to become aristocrat of the city-state of Atarneus. After reaching this elevation Hermias invited Aristotle to his court; and in the year 344 b.c. he rewarded his teacher for past favours by bestowing upon him a sister (or a niece) in marriage. One might suspect this as a Greek gift; but the historians hasten to assure us that Aristotle, despite his genius, lived happily enough with his wife, and spoke of her most affectionately in his will. It was just a year later that Philip, King of Macedon, called Aristotle to the court at Pella to undertake the education of Alexander. It bespeaks the rising repute of our philosopher that the greatest monarch of the time, looking about for the greatest teacher, should single out Aristotle to be the tutor of the future master of the world.

You can imagine treating white women like barter today? But it was healthier than Western feminism.

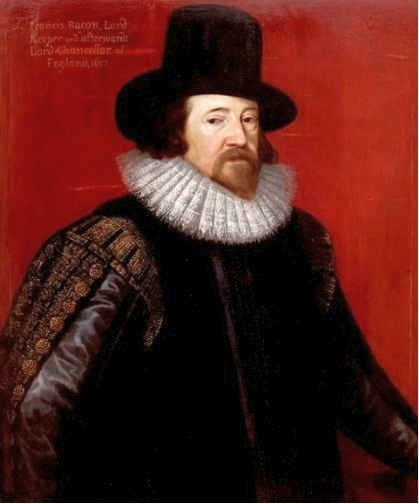

Philip had no sympathy with the individualism that had fostered the art and intellect of Greece but had at the same time disintegrated her social order; in all these little capitals he saw not the exhilarating culture and the unsurpassable art, but the commercial corruption and the political chaos; he saw insatiable merchants and bankers absorbing the vital resources of the nation, incompetent politicians and clever orators misleading a busy populace into disastrous plots and wars, factions cleaving classes and classes congealing into castes: this, said Philip, was not a nation but only a welter of individuals—geniuses and slaves; he would bring the hand of order down upon this turmoil, and make all Greece stand up united and strong as the political centre and basis of the world. In his youth in Thebes he had learned the arts of military strategy and civil organization under the noble Epaminondas; and now, with courage as boundless as his ambition, he bettered the instruction. In 338 b.c. he defeated the Athenians at Chaeronea, and saw at last a Greece united, though with chains. And then, as he stood upon this victory, and planned how he and his son should master and unify the world, he fell under an assassin’s hand.

Durant ignored what I know about psychoclasses: different levels of childrearing from the point of view of empathy toward the child. It is disturbing to read, for example, that according to Plutarch, Olympias, Philip’s wife and the mother of Alexander, was a devout member of the orgiastic snake-worshiping cult of Dionysus. Plutarch even suggests that she slept with snakes in her bed. Although Oliver Stone’s film of Alexander is Hollywood, not a real biography, the first part of the film up to the assassination of Philip is not that bad as to provide an idea of the unhealthy relationship between Olympias and her son.

“For a while,” says Plutarch, “Alexander loved and cherished Aristotle no less than as if he had been his own father; saying that though he had received life from the one, the other had taught him the art of living.” (“Life,” says a fine Greek adage, “is the gift of nature; but beautiful living is the gift of wisdom.”)

But was it wisdom? The real ‘wisdom of the West’ only started with a politician like Hitler and, on the other side of the Atlantic, a white supremacist like Pierce. Ancient philosophers ignored the dangers involved in conquering non-white nations without the policy extermination or expulsion.