The following is my abridgement of chapter 24 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Middle Ages Were Era of Slow, Ordered Evolution

Eastern Europe Had Different Experience With Jews than West

Reformation Resulted in Increased Judaization of Western Europe

Inside the White Citadel, Jews Wreak Havoc on Society

Capitalists, Reds Collaborate Against West

This installment continues the history of the interaction of the Jews with the European peoples, begun in the previous installment, and carries it from the Middle Ages into the modern era.

The salient characteristic of the Middle Ages was order. The feudal society of the early Middle Ages (from ca. 700 until ca. 1200) was a highly structured society: not only did every man have his place and every place its man, but the relationship of each man to every other was strictly defined. From the lord of the manor down to the village idiot, every person was bound to others by mutual responsibilities and obligations.

The corporate society which flourished in Western Europe from the mid-12th century until its destruction by the rise of finance capitalism in the 18th century was able to approach the ideal primarily because it was a substantially homogeneous society, and its institutions had developed organically over a very long period of time.

Both in theory and in practice corporatism had its flaws, the principal one being that it gained stability at the expense of innovation: medieval society was extraordinarily conservative, and technical progress came at a somewhat slower pace than it might have in a less-regulated society. On the other hand, a reasonable degree of stability is always a prerequisite for continuing progress, and the medieval compromise may not have been so bad after all.

Insofar as personal freedom was concerned, the socially irresponsible “do your own thing” attitude definitely was not so common as it is today, but neither was there a lack of opportunities for the adventurous element among the population to give expression to its urges. It should be remembered that the most common theme of the folk tales which had their origin in the Middle Ages—exemplified in the Grimm brothers’ collection—was that of the young man setting out alone into the world to make his fortune. Certainly, there was more personal freedom, in practice, in the Middle Ages for the average craftsman than there was in the capitalist period of mass production which followed.

For our purpose here, the essential thing about medieval society was that it was an ordered, structured society, with a population base which was, in each particular region, homogeneous. Thus, it was a society imbued with certain natural defenses against penetration by alien elements.

The Jew in medieval Europe had relatively little elbow room. He did not fit into the well established, well ordered scheme of things. He was an outsider looking into a self-sufficient world which had little use for his peculiar talents.

This was the situation for the better part of a millennium, and throughout that long period the foremost goal of the Jew was to destroy the order, to break down the structure, to loosen the bonds which held European society together, and thereby to create an opening for himself.

Order is the Jew’s mortal foe. One cannot understand the role of the Jew in modern European history unless one first understands this principle.

It explains why the Jew is the eternal Bolshevik: why he is a republican in a monarchist society, a capitalist in a corporate society, a communist in a capitalist society, a liberal “dissident” in a communist society—and, always and everywhere, a cosmopolitan and a race mixer in a homogeneous society.

And, in particular, it explains the burning hatred the Jews felt for European institutions during the Middle Ages. It explains why the modern Jewish spokesman, Abram Sachar, in his A History of the Jews, frankly admits that the universal attitude of the Jews toward medieval European society was, “Crush the infamous thing!”

Yet, even in the Middle Ages the Jews did not do badly for themselves, and they certainly had little cause for complaint, except when their excesses brought the wrath of their hosts down on their heads. As was pointed out in the previous installment, the Jews established an early stranglehold on the commerce of Europe, monopolizing especially foreign trade.

Their real forte, however, was in two staples of commerce forbidden to most Gentiles in Christian Europe: gold and human flesh. Aristotle’s denunciations of usury had influenced the leaders of the Church against moneylending, and the practice was consequently forbidden to Christians on religious grounds—although the ban was not always strictly observed. The field was left almost entirely to the Jews, who, in contrast to the Christians, used their religion as an explicit justification for usury.

Moses, the purported author of this basis for all Jewish business ethics, was speaking from the experience the Jews had already gained in Egypt when he indicated that the ultimate goal of moneylending to the strangers in a land “to which thou goest” was to “possess” the land. When it came to the slave trade, the words of Moses were not just permissive, but imperative: “Both thy male and female slaves, whom thou shalt have, shall be of the heathen [goyim] that are round about you; of them shall ye buy male and female slaves…” (Leviticus 25:44-46). It is truly said by the Jews themselves that the Hebrew spirit breathes in every word of the Old Testament!

In Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean area the guild system did not reach the full development that it did in the West and the North of Europe, and Jews in Russia, Poland, Lithuania, and parts of Italy engaged in a few trades besides moneylending and slave dealing: the liquor business, in particular. Jews eventually owned most of the inns of Eastern Europe. They also monopolized the garment industry throughout large areas of the East and the South, and the Jewish tailor, the Jewish rag-picker, and the Jewish used clothes peddler are proverbial figures.

The relatively greater opportunities for exploitation of the Gentiles in the East, not to mention the strong presence of the Khazar-descended Jews there, led to a gradual concentration of Europe’s Jews in Poland and Russia during the Middle Ages. By the latter part of the 18th century, half the world’s Jews were living in Poland. Their power became so great that many medieval Polish coins, minted during periods when Jews were in charge not only of collecting the taxes, but also of administering the treasury itself, bore inscriptions in Hebrew. The Jews even acquired title to the land on which many Polish and Russian churches stood, and they then charged the Christian peasants admission to their own churches on Sunday mornings.

In the West the Europeans froze the Jews out of the industrial and much of the commercial life of medieval society; in the East the Jews froze the Europeans out. In much of Eastern Europe, Jews became the only mercantile class in a world of peasants and laborers, and they used all their cunning and all the power of their wealth to keep their Gentile hosts down.

Reaction inevitably set in the East, however, just as it had in the West. The 17th century was a period of great uprisings against the Jews, a period when such heroes as the great Cossack hetman and Jew-killer, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, flourished.

In the 18th century the rulers themselves were finally obliged to take strong measures against the Jews of the East, so bad had the situation become. Russia’s Catherine the Great (1729-96), who had inherited most of Poland’s Jews after the partition of the latter country, extended and enforced prohibitions against them which not only limited their economic activity but banned them altogether from large areas.

It is this which goes a long way toward explaining how the Poles, saddled with a communist government consisting almost entirely of Jews after the Second World War, have been able in the last three decades to do what Adolf Hitler could not: namely, make Poland into a country which is virtually Jew-free today. Of more immediate relevance at this point in our story, it is the relatively weaker natural resistance to Jews in the West which suggests why it was relatively easy for the Jews there to take advantage of the breakdown of the medieval order and the dissolution of long-established social structures in order to make new openings for themselves.

The Reformation

Another factor which undoubtedly made the West more susceptible to the Jews was the Reformation, the lasting effects of which were confined largely to Europe’s northwestern regions, in fact, to the Germanic-speaking regions: Germany, Scandinavia, England and Scotland, Switzerland. The Church of Rome and its Eastern Orthodox offshoot had always been ambivalent in their attitudes toward the Jews. On the one hand, they fully acknowledged the Jewish roots of Christianity, and Jesus’ Jewishness was taken for granted. On the other hand, the Jews had rejected Jesus’ doctrine and killed him, saying, “His blood be on us and on our children” (Matthew 27:25), and the medieval Church was inclined to take them at their word.

In addition to the stigma of deicide the Jews also bore the suspicion which naturally fell on heretics of any sort. During the Middle Ages people took Christianity quite seriously, and anyone professing an unorthodox religious belief, whether he actively sought converts or not, was considered a danger to the good order of the community and to the immortal soul of any Christian exposed to him.

What the Protestant reformers did for the Jews was give the Hebrew Scriptures a much more important role in the life of the peoples of Europe than they had enjoyed previously. Among Catholics it was not the Bible but the Church which was important. The clergy read the Bible; the people did not. The people looked to the clergy for spiritual guidance, not to the Bible.

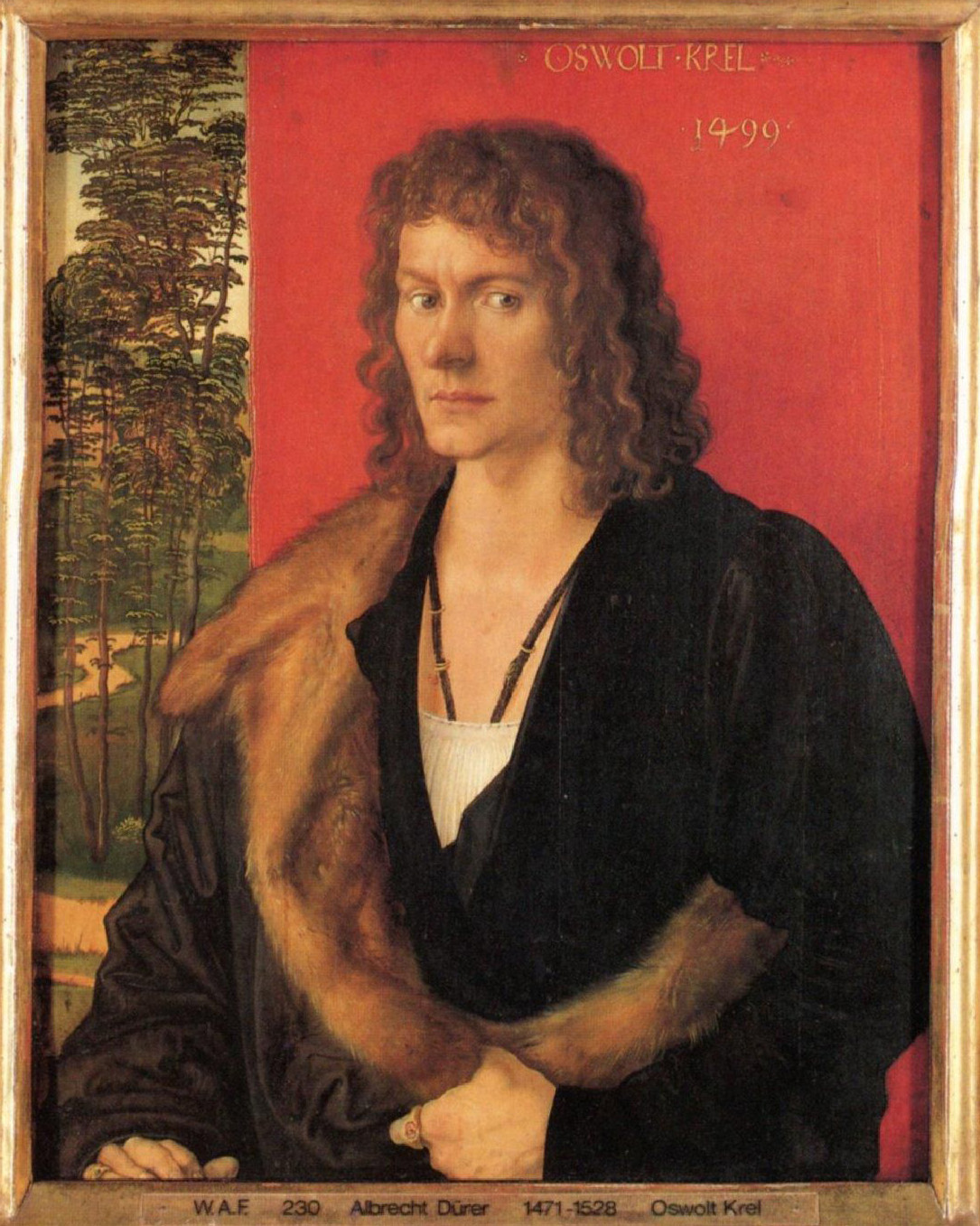

Among Protestants that order was reversed. The Bible became an authority unto itself, which could be consulted by any man. Its Jewish characters—Abraham, Moses, Solomon, David, and the rest—became heroic figures, suffused with an aura of sanctity. Their doings and sayings became household bywords.

It is ironic that the father of the Reformation, Martin Luther, who inadvertently helped the Jews fasten their grip on the West, detested them and vigorously warned his Christian followers against them. His book Von den Jueden und ihren Luegen (On the Jews and their Lies), published in 1543, is a masterpiece.

Luther’s antipathy to the Jews came after he learned Hebrew and began reading the Talmud. He was shocked and horrified to find that the Hebrew religious writings were dripping with hatred and contempt for all non-Jews. Luther wrote:

Do not their Talmud and rabbis say that it is no sin to kill if a Jew kills a heathen, but it is a sin if he kills a brother in Israel? It is no sin if he does not keep his oath to a heathen. Therefore, to steal and rob, as they do with their usury, from a heathen is a divine service. For they hold that they cannot be too hard on us nor sin against us, because they are the noble blood and circumcised saints. We, however, are cursed goyim. And they are the masters of the world and we are their servants, yea, their cattle.

Alas, Luther could not have it both ways. He had already sanctified the Jews by elevating the status of their history, their legends, and their religion to that of Holy Writ. His translation of the Old Testament into German and his dissemination of the Jewish scriptures among his followers vitiated all his later warnings against the Jews. Today the church he founded studiously ignores those warnings.

Luther had recognized the evils in the Christian Church of his day and in the men who ruled the Church. He also recognized the evil in the Jews and the danger they posed to Europe. He had the courage to denounce both the Church and the Jews, and for that the White race will be indebted to him for as long as it endures.

The great tragedy of Luther is that he failed to go one step further and to recognize that no religion of Jewish origin is a proper religion for men and women of European race. When he cut himself and the majority of the Germanic peoples off from Rome, he failed at the same time to cut away all the baggage of Jewish mythology which had been imposed on Europe by Rome. Instead he made of that baggage a greater spiritual burden for his people than it already was.

The consequence was that within a century of Luther’s death much of Northern Europe was firmly in the grip of a new superstition as malignant as the old one, and it was one in which the Jews played a much more explicit role. Before, the emphasis had been on the New Testament: that is, on Christianity as a breakaway sect from Judaism, in which the differences between the two religions were stressed. The role models held up to the peoples of Europe were the Church’s saints and martyrs, most of whom were non-Jewish. The parables taught to children were often of European origin.

Among the Protestants the Old Testament gained a new importance, and with it so did the Hebrew patriarchs as role models, while Israel’s folklore became the new source of moral inspiration for Europe. Perhaps nothing so clearly demonstrates the change, and the damage to the European sense of identity which accompanied it, as the sudden enthusiasm for bestowing Hebrew names on Christian children.

The Reformation did more for the Jews than merely sanctifying the Old Testament. It shattered the established order of things and brought chaos in political as well as spiritual affairs—chaos eagerly welcomed by the Jews. Germany was so devastated by a series of bloody religious wars that it took her a century and a half to recover. In some German principalities two-thirds of the population was annihilated during the conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in the period 1618-1648, commonly known as the “Thirty Years War.”

Everywhere during the 17th century the Jews took advantage of the turmoil, moving back into countries from which they had been banned (such as England), moving to take over professions from which they had been excluded, insinuating themselves into confidential relationships with influential leaders in literary and political circles, profiting from the sufferings of their hosts and strengthening their hold, burrowing deep into the rubble and wreckage of medieval society so that they could more easily undermine whatever rose in its stead.

An 1806 French print depicts

Napoleon Bonaparte emancipating the Jews

In the following century came Europe’s next great cataclysm, which broke down what was left of the old order. It was the French Revolution—and it was the first major political event in Western Europe in which Jews played a significant role, other than as financiers. Even so, public feeling against the Jews was such that they still found it expedient to exercise much of their influence through Gentile front men.

Honore Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau (1749-91), the Revolution’s fieriest orator—the spendthrift, renegade son of an aristocrat, disowned by his father and always in need of a loan—was one of these. Another was the bloodthirsty monster Maximilien Marie Isidore de Robespierre (1758-94), dictator of the Revolutionary Tribunal which kept the guillotine busy and spilled France’s best blood into the gutters of Paris while the rabble cheered. Both Mirabeau and Robespierre worked tirelessly for their Jewish patrons, supporting legislation granting new rights and privileges to the Jews of France and denouncing French patriots who opposed the Jewish advances.

It was in the new series of European wars spawned by the Revolution, in which Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) was the leading figure, that the Jews extended the gains they had made in France to much of the rest of Europe. Behind Napoleon’s armies, which were kept solvent by Jewish moneylenders, marched a ragtag band of Jews to oversee the pulling down of all barriers against their brethren in each country in which French arms triumphed. Ghettos were abolished, all restrictions on Jewish activities were declared void, and anyone who spoke out against the Jews was in danger of being put before a military firing squad.

Despite the enormous services he performed for the Jews, it is clear from his comments, on many different occasions, that Napoleon personally despised them. “The Jews are a vile people, cowardly and cruel,” he said in reference to some of the atrocities committed by Jews during the Reign of Terror.

In a letter of March 6, 1808, to his brother Jerome, Napoleon wrote: “I decided to improve the Jews. But I do not want more of them in my kingdom. Indeed, I have done all to prove my scorn of the vilest nation in the world.” And when, in 1807, Napoleon issued decrees limiting the extent to which Jewish moneylenders could prey on the French peasantry, the Jews screamed in rage against him.

But the damage had already been done; Napoleon had pulled down the last of the barriers, and by the time of his disgrace and exile the Jews were solidly entrenched nearly everywhere.

It was those Jews who pushed their way into the professions—into teaching Gentile university students, into writing books for Gentile readers, into composing music for Gentile audiences, into painting pictures and directing films for Gentile viewers, into interpreting and passing judgment on every facet of Gentile culture and society for Gentile newspaper readers—who really got inside the Gentile citadel.