Hold Back This Day is a dystopian science-fiction novel about a future in which a totalitarian government promotes universal miscegenation to eliminate all racial differences—in the name of diversity, of course.

Hold Back This Day is a dystopian science-fiction novel about a future in which a totalitarian government promotes universal miscegenation to eliminate all racial differences—in the name of diversity, of course.

Category: Literature

Anti-white dystopia

“We have the last unblended arrivals from Europe Zone 5—in particular from Iceland Sector 15.”

Jeff observed studiously, noting how the black students from Borneo and New Guinea were being purposely intermingled with various blondes, brunettes, and redheads of European heritage.

“As demonstrated here, these Europe Zone candidates are entirely Skintone 1s and 2s. Like their darker counterparts, they too are far removed from the government ideal that the World Gov is very near to achieving…”

“Which is a world Skintone Class 5s,” Jeff amplified, unconsciously parroting the government party line. [p. 11]

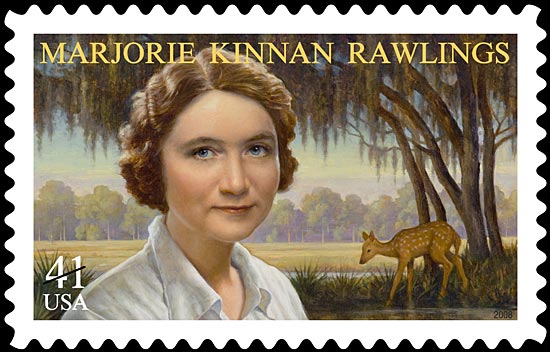

The Yearling, 10

“Hey, Ma, Flag’ll soon be a yearlin’. Won’t he be purty, Ma, with leetle ol’ horns? Won’t his horns be purty?”

“He’d not look purty to me did he have a crown on. And angel’s wings.”

He followed her to cajole her. She sat down to look over the dried cow-peas in the pan. He rubbed his nose over the down of her cheek. He liked the furry feel of it.

“Ma, you smell like a roastin’ ear. A roastin’ ear in the sun.”

“Oh git along. I been mixin’ cornbread.”

“‘Tain’t that. Listen, Ma, you don’t keer do Flag have horns or no. Do you?”

“Hit’ll be that much more to butt and bother.”

He did not press the point. Flag was in increasing disgrace, at best. He had learned to slip free from the halter about his neck. When it was tightened so that he could not get out of it, he used the same tactics that a calf used against restraint. He strained against it until his eyes bulged and his breathing choked, and to save his perverse life, it was necessary to release him. Then when he was free, he raised havoc. There was no holding him in the shed. He would have razed it to the ground. He was wild and impudent. He was allowed in the house only when Jody was on hand to keep up with him. But the closed door seemed to make him possessed to enter. If it was not barred, he butted it open. He watched his chance and slipped in to cause some minor damage whenever Ma Baxter’s back was turned.

♣ ♣ ♣

I don’t want to add more excerpts. But I must say that an incident narrated in the rest of the tale, which I read this year, shocked me. I could easily write a long, detailed entry for my blog on Alice Miller, but child abuse is a subject that does not interest the readers of WDH.

A couple of days ago I caught my father telling his grandson that instead of watching TV for hours he should be reading the beautiful literature for young people, and he mentioned the beauty of a Julius Verne novel. But he’s a hypocrite, since his grandson does exactly what my father does: watching TV for hours everyday and, even in his late eighties, still going to the theater to watch Hollywood filth.

With classics like The Yearling I find it almost a sacrilege that adults are allowing their kids to watch TV. Although I only read The Yearling as an adult, I must say that as a child Wyeth’s illustrations provided some homely zest and a sense of trust in life and in one’s own parents that is difficult to transmit in words.

If anyone actually read the whole novel and is curious about why the culmination of the story surprised me so much, let me know and we can discuss it here.

Spoilers for those who haven’t read it!

Educated homosexuals like to pull out the old Ancient Greco-Roman card that the liberals use. They project their values onto an idealized past that never existed in order to legitimize their lifestyles today.

Judge it by yourself. What could be more decadent in the Greco-Roman world than the homoerotic adventures recounted in a novel written in times of Nero or Caligula? However, classic pederasty was not meant for coeval adults, as is the LGBT movement of today.

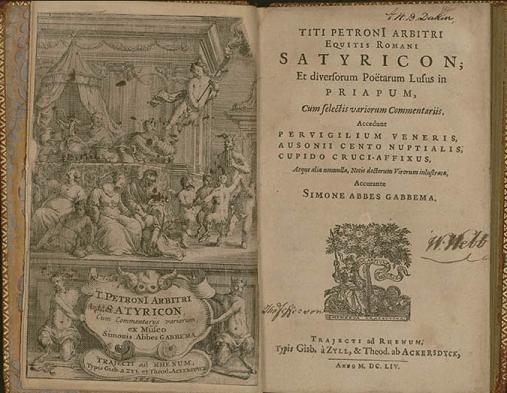

Below I include my translation of the prologue by Jacinto Leon Ignacio to one of the Spanish translations of Petronius’ novel (ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages):

Rome,

centuries ago

In the vast and important Greek and Roman literature from which we still live, there are just a few novelists. Maybe for an overwhelming majority of illiterates it would had been much more affordable the theater, which is enough to listen, that the written narrative which must be read. The same was true of poetry and the rhapsodies recited in public.

The fact is that in Greece there are only a few examples of novels, apart of Longus, and from the Romans only Apuleius and Petronius, whose work we offer here.

It appears that, at the time, the Satyricon enjoyed considerable popular success, for both Tacitus and Quintilian commented it in their manuscripts, although it is apparent that neither knew it directly, only from hearsay. It is likely that they did not grant it much literary value because its style and form collided with all the concepts in vogue.

However, the Satyricon was not lost and copies were kept in the Middle Ages, while jealously concealed because of its subject matter [pederasty] and for being the work of a pagan. The work continued to be ignored by the public to the point that only scholars knew its title, but believed it was lost.

Therefore, a scandal broke when, in 1664, appeared the first edition of Pierre Petit.

Soon after, the Satyricon was translated into several languages, including ours, with such success that has made it one of the great bestsellers in history. There were those who sought to take advantage that the work is incomplete, rewriting it to their liking. It was easy nevertheless to expose them.

Presumably, however, the author would not work at top speed like if we should go to a literary prize. He seems to have devoted years to this task. Do not forget that what is now known are only fragments of the original, estimated in twenty books. The author might have started writing when Caligula reigned and Nero followed, to see the publication during the reign of the next emperor. It can be no coincidence that the book mentions contemporary events known to all, or that the author considered worth mentioning many names.

This is a job too conscientious not to be the work of a professional. Moreover, the action does not take place in Rome, but in the provinces and almost none of the men are Latins. It seems as if the author had had an interest in showing the reality of the empire, a reality ignored in the capital.

The novel consists merely of the travel story of [Encolpius] and his servant Gitone through different locations. The incidents, sometimes unrelated, their adventures and the people they encounter are the text of the Satyricon, which lacks a plot as was the style of the epoch. We could actually say that it consists of countless short stories of the two protagonists. This technique influenced many centuries later the books of chivalry, the picaresque and even Don Quixote. Throughout many incidents the author reveals us an extraordinary real view of the life in the Roman provinces, although tinged with irony.

Petronius simply tells us what he saw. In a way, his novel was an approach to realism, leaving aside the epic tone of the tragedies to focus on current issues, as Aristophanes did in Greece. And that was the pattern followed by Petronius. There is a huge difference between his style and that of other contemporary writers.

Poets, despite their undoubted genius, are pompous and in the tragedies the dialogues are extremely emphatic. Petronius by contrast, remains accessible to everyone. He expressed himself in a conversational tone, which justifies the use of a first person that conveys the feeling that someone is telling us a live tale. That’s why today we can read his Satyricon with the same interest of his times and nothing of its freshness is lost.

Writing is, in a sense, a childbirth with the same joys and suffering. Both things must have accompanied Petronius in this trip with [Encolpius] and Gitone through the decline of Rome.

JVLIAN excerpts – V

Julian the Apostate was the nephew of the Emperor Constantine the Great. Julian ascended the throne in A.D. 361, at the age of twenty-nine, and was murdered four years later after an unsuccessful attempt to rebuke Christianity and restore the worship to the old gods.

The Memoir of Julian Augustus

From the example of my uncle the Emperor Constantine, called the Great, who died when I was six years old, I learned that it is dangerous to side with any party of the Galileans, for they mean to overthrow and veil those things that are truly holy. I can hardly remember Constantine, though I was once presented to him at the Sacred Palace. I dimly recall a giant, heavily scented, wearing a stiff jeweled robe. My older brother Gallus always said that I tried to pull his wig off. But Gallus had a cruel humor, and I doubt that this story was true. If I had tugged at the Emperor’s wig, I would surely not have endeared myself to him, for he was as vain as a woman about his appearance; even his Galilean admirers admit to that.

From my mother Basilina I inherited my love of learning. I never knew her. She died shortly after my birth, 7 April 331. She was the daughter of the praetorian prefect Julius Julianus. From portraits I resemble her more than I do my father; I share with her a straight nose and rather full lips, unlike the imperial Flavians, who tend to have thin hooked noses and tight pursed mouths. The Emperor Constantius, my cousin and predecessor, was a typical Flavian, resembling his father Constantine, except that he was much shorter. But I did inherit the Flavian thick chest and neck, legacy of our Illyrian ancestors, who were men of the mountains. My mother, though Galilean, was devoted to literature. She was taught by the eunuch Mardonius, who was also my tutor.

From my cousin and predecessor, the Emperor Constantius, I learned to dissemble and disguise my true thoughts. A dreadful lesson, but had I not learned it I would not have lived past my twentieth year.

In the year 337 Constantius murdered my father. His crime? Consanguinity. I was spared because I was six years old; my half-brother Gallus—who was eleven years old—was spared because he was sickly and not expected to live.

Yes, I was trying to imitate the style of Marcus Aurelius to Himself, and I have failed. Not only because I lack his purity and goodness but because while he was able to write of the good things he learned from a good family and good friends, I must write of those bitter things I learned from a family of murderers in an age diseased by the quarrels and intolerance of a sect whose purpose is to overthrow that civilization whose first note was stuck upon blind Homer’s lyre.

“Why were you so ungrateful to our gods

as to desert them for the Jews?”

—Julian, addressing the Christians

Priscus to Libanius

Athens, June 380

I send you by my pupil Glaucon something less than half of the Emperor Julian’s memoir. It cost me exactly 30 solidi to have this much copied. On receipt of the remaining fifty solidi I shall send you the rest of the book.

We can hardly hope to have another Julian in our lifetime. I have studied the edict since I wrote you last, and though it is somewhat sterner in tone than Constantine’s, I suspect the only immediate victims will be those Christians who follow Arius. But I may be mistaken…

I never go to evening parties. The quarter I referred to in my letter was not the elegant street of Sardes but the quarter of the prostitutes near the agora. I don’t go to parties because I detest talking-women, especially our Athenian ladies who see themselves as heiress to the age of Pericles. Their conversation is hopelessly pretentious and artificial.

Hippia and I get along rather better than we used to. Much of her charm for me has been her lifelong dislike of literature. She talks about servants and food and relatives, and I find her restful. Also, I have in the house a Gothic girl, bought when she was eleven. She is now a beautiful woman, tall and well made, with eyes grey as Athena’s. She never talks. Eventually I shall buy her a husband and free them both as a reward for her serene acceptance of my attentions, which delight her far less than they do me.

But then Plato disliked sexual intercourse between men and women. We tend of course to think of Plato as divine, but I am afraid he was rather like our old friend Iphicles, whose passion for youths has become so outrageous that he now lives day and night in the baths, where the boys call him the queen of philosophy.

Hippia joins me in wishing for your good—or should I say better?—health.

The memoir. It will disturb and sadden you. I shall be curious to see how you use this material.

You will note in the memoir that Julian invariably refers to the Christians as “Galileans” and to their churches as “charnel houses,” this last a dig at their somewhat necrophile passion for the relics of dead men. I think it might be a good idea to alter the text, and reconvert those charnel houses into churches and those Galileans into Christians. Never offend an enemy in a small way.

Here and there in the text, I have made marginal notes. I hope you won’t find them too irrelevant.

Covington’s ‘The Brigade’

The Brigade excerpts, chapter I

The Brigade excerpts, chapter II

The Brigade excerpts, chapter III

The Brigade excerpts, chapter IV

The Brigade excerpts, chapter V

The Brigade excerpts, chapter VI

The Brigade excerpts, chapter VII

Chechar’s ten must-reads

1. Hellstorm (excerpts here)

Hellstorm is the first book in my list for the reasons explained below this post. Whites will not regain a proper self-esteem unless and until the big lies of omission about the Second World War are exposed with all our heart and being. If the Allied crime is not understood, assimilated and atoned for, my prediction is that the white people will perish.

2. Who We Are (excerpts here)

3. March of the Titans (excerpts here)

It is not enough to know the real history of the century when we were born, as well as the astronomic lies of omission of the academia and the media about the wars. The fact is that, unlike the other races—brown, black and yellow—in the last millennia whites have managed to find themselves as an endangered species more than once, and this has paramount importance to understand our times. I find it incredible that only a few white nationalists have been interested in the history of their race; proof of it is that these two splendid books by Arthur Kemp and William Pierce are not the main bestsellers in the community. (Unlike Kemp’s 2011 edition of March of the Titans, Pierce’s Who We Are is not available in book form—he died before sending the manuscript to the printers.)

4. A People that Shall Dwell Alone

5. Separation and its Discontents

6. The Culture of Critique

The Jewish problem is one of the greatest problems in the western world, and, pace counter-jihadists and other naïve conservatives, no man can be considered mature until he has striven to face it. Therefore, besides readable and very entertaining histories of the white race, a specific study on the Jewish question is fundamental. The above books comprise Kevin MacDonald’s magnum opus on Jewry.

MacDonald’s preface to The Culture of Critique (see link above), which he wrote four years after finishing the trilogy, can be read as a didactic introduction to the whole trilogy.

Presently I am reading the sections of the second book on how otherwise individualist whites elaborated collectivist group strategies in the form of the Early Medieval Church and, more recently, the (aborted) National Socialist movement in Germany. These are mirror images of Judaism as a reaction to a perceived group conflict, precisely what the blogger Svigor has been calling “towards white Zionism.” Although MacDonald’s study is academic, what I am reading now in Separation and its Discontents is pretty captivating. It seems to me that a future movement of white collectivism inspired in these precedents is the only way to racial preservation.

8. The Brigade

Objective scholarship is not enough to get the picture of what white nationalism is. We also need a thoroughgoing subjective vision, what I call soul-building. We need novels depicting future reactions or group conflicts against the tribe, other non-white invaders and the white traitors. William Pierce’s Turner Diaries inaugurated a literary genre that fills the gap. For those who have no stomach for Pierce’s extermination fantasies I would recommend the best novel of Harold Covington’s quintet, The Brigade, an absolute treat.

9. Toward the White Republic (excerpts here)

This collection of essays authored by Michael O’Meara is the best pamphlet to date on white nationalism. Like the Hellstorm book, we can even send gifts of this slim book to our friends and acquaintances. Unlike most white nationalists, O’Meara is a genuine revolutionary, not a mere reactionary. It is a shame that after being fired by the academia for political incorrectness, as far as I know Professor O’Meara has not found a sponsor within the white movement.

10. Collected essays by F.R. Devlin (example here)

The last “book” of my list has not been published all together, not even online. It’s an imaginary book in my mind containing the best essays of F. Roger Devlin on how feminism has been destroying our morals, our white genotype, phenotype and even our extended phenotype in the latest decades. (Yes: I am old enough to remember the times when the institution of marriage was rock-solid among my relatives.) Those editors in the white movement who are promoting homosexuality ought to mend their ways and, instead of publishing books claiming that “homophobia” is part of the Jewish culture of critique, they should be collecting Devlin’s essays under a single cover. (I confess that hetero-sexual family values are exactly the conscious and unconscious force that drives my mind into the white movement.)

I wish that Devlin’s Collected essays as well as Pierce’s Who We Are be published in hardcovers before the currency crash (coming under Obama’s second term) makes unaffordable any gathering of the best pro-white literature in the market.

Enjoy the reading! After the dollar crashes and the internet is censored you will regret not having a home library!

Young William Pierce

______ 卐 ______

Since then he has been issuing idiotic proclamations about “restoring the Constitution,” and holding new elections to “re-establish the republican form of government intended by the Founding Fathers,” whatever that means.

And he has denounced our radical measures in the south as “communism.” He is appalled that we didn’t hold some sort of public referendum before expelling the non-Whites and that we didn’t give individual trials to the Jews and race-criminals we dealt with summarily.

Doesn’t the old fool understand that the American people voted themselves into the mess they’re in now? Doesn’t he understand that the Jews have taken over the country fair and square, according to the Constitution? Doesn’t he understand that the common people have already had their fling at self-government, and they blew it?

Where does he think new elections can possibly lead now, with this generation of TV-conditioned voters, except right back into the same Jewish pigsty? And how does he think we could have solved our problems down here, except by the radical measures we used?

______ 卐 ______

“Finally, we warn you that, in any event, we intend to liberate, first, the entire United States and then the remainder of this planet. When we have done so we will liquidate all the enemies of our people, including in particular all White persons who have consciously aided those enemies.”

______ 卐 ______

Then we formed the people into labor brigades to carry out a number of necessary functions, one of which was the sanitary disposal of the hundreds of corpses of refugees. The majority of these poor creatures were White, and I overheard one of our members refer to what happened to them as “a slaughter of the innocents.”

I am not sure that is a correct description of the recent holocaust. I am sorry, of course, for the millions of White people, both here and in Russia, who died—and who have yet to die before we have finished—in this war to rid ourselves of the Jewish yoke. But innocents? I think not. Certainly, that term should not be applied to the majority of the adults.

After all, is not man essentially responsible for his condition—at least, in a collective sense? If the White nations of the world had not allowed themselves to become subject to the Jew, to Jewish ideas, to the Jewish spirit, this war would not be necessary. We can hardly consider ourselves blameless. We can hardly say we had no choice, no chance to avoid the Jew’s snare. We can hardly say we were not warned.

______ 卐 ______

Eventually the System began regrouping its forces elsewhere, to meet new challenges in other parts of the country.

And then, just as the Jews had feared, the flow of Organization activists turned exactly 180 degrees from what it had been in the weeks and months. From scores of training camps in the liberated zone, first hundreds, then thousands of highly motivated guerrilla fighters began slipping through the System’s diminishing ring of troops and moving eastward. With these guerrilla forces the Organization followed the example of its Baltimore members and rapidly established dozens of new enclaves, primarily in the nuclear-devastated areas, where System authority was weakest.

The Detroit enclave was initially the most important of these. Bloody anarchy had reigned among the survivors in the Detroit area for several weeks after the nuclear blasts of September 8. Eventually, a semblance of order had been restored, with System troops loosely sharing power with the leaders of a number of Black gangs in the area. Although there were a few isolated White strongholds which kept the roving mobs of Black plundvers and rapists at bay, most of the disorganized and demoralized White survivors in and around Detroit offered no effective resistance to the Blacks, and, just as in other heavily Black areas of the country, they suffered terribly.

Then, in mid-December, the Organization seized the initiative. A number of synchronized lightning raids on the System’s military strong points in the Detroit area resulted in an easy victory. The Organization then established certain patterns in Detroit which were soon followed elsewhere. All captured White troops, as soon as they had laid down their weapons, were offered a chance to fight with the Organization against the System. Those who immediately volunteered were taken aside for preliminary screening and then sent to camps for indoctrination and special training. The others were machine-gunned on the spot, without further ado.

The same degree of ruthlessness was used in dealing with the White civilian population. When the Organization’s cadres moved into the White strongholds in the Detroit suburbs, the first thing they found it necessary to do was to liquidate most of the local White leaders, in order to establish the unquestioned authority of the Organization. There was no time or patience for frying to reason with shortsighted Whites who insisted that they weren’t “racists” or “revolutionaries” and didn’t need the help of any “outside agitators” in dealing with their problems, or who had some other conservative or parochial fixation.

The Whites of Detroit and the other new enclaves were organized more along the lines described by Earl Turner for Baltimore than for California, but even more rapidly and roughly. In most areas of the country there was no opportunity for an orderly, large-scale separation of non-Whites, as in California, and consequently a bloody race war raged for months, taking a terrible toll of those Whites who were not in one of the Organization’s tightly controlled, all-White enclaves.

Food became critically scarce everywhere during the winter. The Blacks lapsed into cannibalism, just as they had in California, while hundreds of thousands of starving Whites, who earlier had ignored the Organization’s call for a rising against the System, began appearing at the borders of the various liberated zones begging for food. The Organization was only able to feed the White populations already under its control by imposing the severest rationing, and it was necessary to turn many of the latecomers away.

Those who were admitted—and that meant only children, women of childbearing age, and able-bodied men willing to fight in the Organization’s ranks—were subjected to much more severe racial screening than had been used to separate Whites from non-Whites in California. It was no longer sufficient to be merely White; in order to eat one had to be judged the bearer of especially valuable genes.

______ 卐 ______

As everyone is aware, the bands of mutants which roam the Waste remain a real threat, and it may be another century before the last of them has been eliminated and White colonization has once again established a human presence throughout this vast area.

But it was in [that] year, according to the chronology of the Old Era—just 110 years after the birth of the Great One—that the dream of a White world finally became a certainty. And it was the sacrifice of the lives of uncounted thousands of brave men and women of the Organization during the preceding years which had kept that dream alive until its realization could no longer be denied.

Among those uncounted thousands Earl Turner played no small part. He gained immortality for himself on that dark November day 106 years ago when he faithfully fulfilled his obligation to his race, to the Organization, and to the holy Order which had accepted him into its ranks. And in so doing he helped greatly to assure that his race would survive and prosper, that the Organization would achieve its worldwide political and military goals, and that the Order would spread its wise and benevolent rule over the earth for all time to come.

The End

Alex Linder said…

I don’t think anyone could like Turner Diaries. It is a disturbing book, frightening even—even if you agree with him, as I obviously do. But it is undeniably heavy. In a way that Covington’s novels, so beloved of Johnson, are not. They are almost fruity in how bubbly the characters are, given the situation, although they are certainly enjoyable escapism.

Pierce’s work has a gravitas befitting a genocidal struggle, and no other WN novel has come even close to it except Raspaille’s Camp of the Saints. Raspaille is a better artist than Pierce, by a long stretch, but both books are about equally heavy, in that they impress and linger.