Or:

How WNsts who say that they don’t believe the media,

they actually believe the media

The End of The Road documentary (YouTube clips here) that I have been advertizing on how the world as we know it will end soon—what I’m starting to call the eschaton—was released last year. People should take heed that Edgar Steele advised all of us to storage food for at least a year, before the System put him in jail.

On May 28, 2012 I posted an expanded entry of the below post. That’s why the first threaded comments date from those times. I am just editing and relocating it to August 1, 2013 for further context to what I said yesterday about my fundraising thermometer. Pay special attention to what the commenters in the entry itself say about the psychology of normalcy bias, and how white nationalists who say that they don’t believe in the media, they actually believe in the media.

Below, a miscellaneous collection of what can be read in several blogsites about the coming eschaton:

End of The Road portrays eleven influential commentators within the finance and investment communities, as they share their knowledge of our current financial structure. Through each of their narratives, a story is built which chronicles the current economic dilemma and paints a picture of the world’s financial future.

Cast:

Eric Sprott,

James Turk,

Jim Puplava,

Peter Schiff,

Bill Murphy,

Dimitri Speck,

Mike Maloney,

James Rickards,

Edward Griffin,

Adam Fergusson,

Alasdair Macleod

These gentlemen have an intimate understanding of the ongoing policies—read manipulation—central bankers have utilized in order to keep currencies and markets from imploding. If you are familiar with central banking you will have come to understand that all fiat currencies have gone to zero (see the Mike Maloney clip in the comments section). This time it will be vastly different because it is occurring simultaneously, in the context of a macro-level, around the entire world.

From 100th Monkey Films:

In 2008 the world experienced one of the greatest financial turmoils in modern history. Markets around the world started crashing, stock prices plummeted, and major financial institutions, once thought to be invincible, started showing signs of collapse. Governments responded quickly, issuing massive bailouts and stimulus packages in an effort to keep the world economy afloat.

While we’re told that these drastic measures prevented a total collapse of our system, a growing sense of unease has spread throughout the population. In the world of finance, indeed in all facets of modern life, cracks have started to appear. What lies ahead as a result of these bold “money printing” measures? Was the financial crisis solved, or were the problems merely kicked down the road?

B. Paul said…

It looks interesting but I’m not sure that it [End of the Road documentary] will have anything new for regular Collapsenet users. Perhaps it will be a good tool for friends/family, if it doesn’t come out too late. However, some Zombies will never get it, no matter what evidence they are presented with or how clearly, concisely and urgently it is presented.

Lydian Mode said…

I’m starting to wonder if some people aren’t supposed to get it. Maybe they’re the ones who are supposed to die off. Maybe they are missing a vital evolutionary gene or something that’s keeping them from realizing that they are living in a very dangerous time and should think about some options to help them survive. Who knows? I just hate thinking about all the innocent children who are dependent upon their Zombie parents for their survival. This is the part of collapse I really, really dread to see happening.

James Beckmeyer said…

Most people are far too busy and wrapped up with their lives to “get it.” What we want them to “get” sounds outright loony to them, and since few people want to believe in loony shit, they will never get it. This is a perfect set-up for a very hard fall—much harder than the Soviet Union whose citizenry, for the most part, had a belief system much more rooted in reality than the US.

Businessman said…

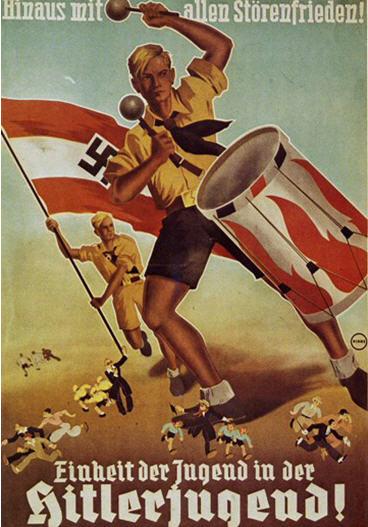

This discussion reminds me of a quote I saw on video given by a late historian and political activist, which I’m paraphrasing here: “These people who tell you that they don’t believe the media… they believe the media.”