By early 1920, Hitler had found two new homes. On leaving the army, he found lodgings as a sub-tenant of Ernst and Maria Reichert in Thierschstrasse no. 41, in the inner Munich suburb of Lehel. It was a very modest berth in a working- and lower-middle-class neighbourhood. Hitler was an easy-going resident, who never locked his doors and allowed the Reicherts to use his gramophone and books during his frequent absences. We do not know what exactly he read, but the best-thumbed surviving volumes from his collection relate to history and art, whereas those on race and the occult gave the impression of being unread. [emphasis added]

As we said recently, it is the poet who creates nations, not the scientist (e.g. the scientific books on race realism published by Jared Taylor). ‘The historical course offered by myth, in contrast to the inherently passive determinism of scientific rationalism’, writes Michael O’Meara, ‘is a choice for heroes, not for bookworms or computer hobbyists’. Also, history is the most important subject in the eyes of the raven, who spends his life fused to the Weirwood looking at the past of his civilisation. Like Bran, the raven’s pupil, Hitler perfectly understood this.

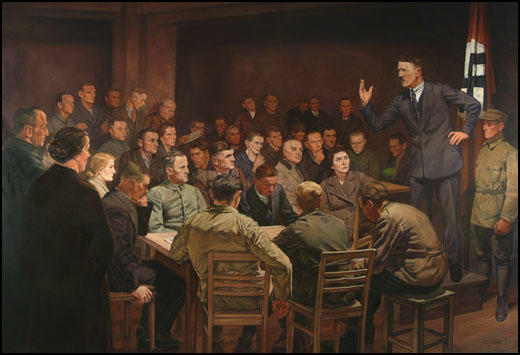

His new professional and political home was the DAP, which was renamed the ‘National Socialist German Workers’ Party’ (NSDAP) in the course of 1920. Hitler was by now a recognized quantity on the local right-wing scene…

Hitler believed political organization without propaganda was pointless. His main concern at this point was to use the party as a platform to disseminate and elaborate his ideas. He was involved in the drafting of the twenty-five point NSDAP (technically DAP) programme in February 1920, though it is unclear whether he can claim sole authorship. The first four related to national integrity, foreign policy and territorial expansion; the next four concerned race, mostly strictures against the Jews. Hitler turned Wilson’s idea of ‘self-determination’ back on the Allies with his call for ‘the unification of all Germans in a Greater Germany on the basis of the right of peoples to self-determination’. More than that, he demanded ‘Land and soil (colonies) to feed our people and to settle our surplus population’, the first unambiguous documented articulation of what subsequently became the Lebensraum concept. The geographic location of these future ‘colonies’ was not specified but at this time Hitler seems to have had overseas territories in mind…

Hitler paid close attention to the iconography underpinning the message. A black swastika of his design on a white circle with red background was first flown as the official party emblem at a meeting in Salzburg in August 1920. In one of his very few excursions into the occult, Hitler praised the swastika—as a ‘symbol of the sun’ which sustained a ‘cult’ of light among a ‘community based on Aryan culture’, not only in Europe, but in India… as well. The use of the old imperial black, white and red colours was a calculated affront to the black, red and gold of the Weimar flag.

‘The red is social,’ he later explained, ‘the white is national, and the swastika is anti-Semitic.’ By mounting the symbol diagonally, Hitler cleverly conveyed a sense of dynamism and movement.

‘The red is social,’ he later explained, ‘the white is national, and the swastika is anti-Semitic.’ By mounting the symbol diagonally, Hitler cleverly conveyed a sense of dynamism and movement.

Four months later, he oversaw the purchase of the Volkischer Beobachter newspaper and the Franz Eher Verlag, financed in part by a loan from a Reichswehr slush fund guaranteed by Dietrich Eckart, which gave the party a media platform with a print run of 8,000-17,000 appearing three times a week; after many ups and downs, the Volkischer Beobachter became a daily on 8 February 1923.

Here it is noticeable that the white nationalists haven’t really broken ideologically with the ethnocidal System. If they had broken away with it, they would have had the initiative to, at the very least, come up with a new flag very different from the American flag, as well as having incredibly different heroes. In my previous post, I quoted what Robert Morgan said yesterday. This is what we read on pages 175-176 of my book Daybreak: ‘Stars and Stripes? As Morgan explained to us, the personalities sculpted on Mount Rushmore represent ideals that would eventually lead to white decline’:

The Old America is dead? I don’t think so. Symbolic of the Old America, and chiseled into Mt. Rushmore, are four American ‘heroes’, whose exploits demonstrate the white man’s biggest problem: himself. First we have George Washington, who magnanimously freed his slaves, but only after his death, after which he had no further use for them. How many white Americans have been robbed, murdered, or raped by the descendants of those slaves? Quite a few, no doubt.

Thanks George!

Then comes Lincoln, who authorized the murders of hundreds of thousands of whites on his way to freeing the slaves and then turning them loose on his countrymen. His admirers say that, like Martin Luther King, he had a dream. But Abe’s dream was that all of the negroes would volunteer to leave these shores. How racist! Amazingly, and no doubt a big surprise to Abe, few wanted to do so.

Thanks a lot, ‘honest’ Abe!

Then we have Thomas Jefferson, a randy old fellow who was probably nailing his quadroon slave Sally Hemings, and likely had a child by her. His was the colonial prototype for the long American tradition of race mixing (a.k.a. white racial suicide).

Thanks Tom! You set a fine example.

Last is Teddy Roosevelt, the original progressive. He was an advocate for women’s suffrage, yet another step in the direction of the hallowed American cause of ‘equality’, and it’s painfully obvious how that turned out. Also, he favored a powerful federal government, just as do progressives today. To fund such a government he favored the income tax, a noose into which the American public eagerly thrust its neck.

The current unrest is only more of the same white racial self-destruction. So the Old America isn’t dead. Its spirit is just flying new flags, reorganized under the banners of BLM and antifa. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

An 1849 epigram by Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, it means: ‘The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing’. As long as the American racial right doesn’t produce a new flag with colours different from those chosen by Hitler, but that the new flag displays the swastika, their movement will be la même chose: the American way of white ethnocide.

So, considering that musically Strauss was heavily influenced by Wagner, and that Hitler himself also was a fanatic Wagnerian, why not be tolerant of bridges? Ultimately, that bridge, from the Christian Bach to the half-pagan Wagner, lead to Strauss and eventually to us (as a child and pubescent I listened a lot of times to the LP we see on the left). It could even be argued, as I do in the featured post, that Hitler and Rosenberg themselves could be bridges to an even more refined NS than the one they promoted (an Aryan Jesus, etc.).

So, considering that musically Strauss was heavily influenced by Wagner, and that Hitler himself also was a fanatic Wagnerian, why not be tolerant of bridges? Ultimately, that bridge, from the Christian Bach to the half-pagan Wagner, lead to Strauss and eventually to us (as a child and pubescent I listened a lot of times to the LP we see on the left). It could even be argued, as I do in the featured post, that Hitler and Rosenberg themselves could be bridges to an even more refined NS than the one they promoted (an Aryan Jesus, etc.).