Originally I posted this article on April 25, 2012. But now that I have been postulating that the One Ring of greed and power—that we might start calling “the Aryan Problem”—could be the main factor in the West’s darkest hour, I am moving it at the top of this blog.

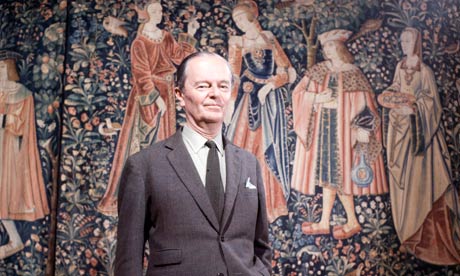

Below, some excerpts of “Heroic Materialism,” the last chapter of Civilisation by Kenneth Clark. (For an introduction to these series, see here.) Ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages. Also, the headings don’t appear in the original text:

The westerners’ new god: Mammon

Imagine an immensely speeded up movie of Manhattan Island during the last hundred years. It would look less like a work of man than like some tremendous natural upheaval. It’s godless, it’s brutal, it’s violent—but one can’t laugh it off, because in the energy, strength of will and mental grasp that have gone to make New York, materialism has transcended itself. It took almost the same time to reach its present conditions as it did to complete the Gothic cathedrals. At which point a very obvious reflection crosses one’s mind: that the cathedrals were built to the glory of God, New York was built to the glory of mammon—money, gain, the new god of the nineteenth century. So many of the same human ingredients have gone into its construction that at a distance it does look rather like a celestial city. At a distance. Come closer and it’s not so good. Lots of squalor, and, in the luxury, something parasitical.

Blake’s Satan

One sees why heroic materialism is still linked with an uneasy conscience. The first large iron foundries like the Carron Works or Coalbrookdale, date from about 1780. The only people who saw through industrialism in those early days were the poets. Blake, as everybody knows, thought that mills were the work of Satan. ‘Oh Satan, my youngest born… thy work is Eternal death with Mills and Ovens and Cauldrons.’

The [slave] trade was prohibited in 1807, and as Wilberforce lay dying in 1835, slavery itself was abolished. One must regard this as a step forward for the human race, and be proud, I think, that it happened in England. But not too proud. The Victorians were very smug about it, and chose to avert their eyes from something almost equally horrible that was happening to their own countrymen.

In its early stages the Industrial Revolution was also a part of the Romantic movement. And here I may digress to say that painters had for long used iron foundries to heighten the imaginative impact of their work with what we call a romantic effect; and that they had introduced them into pictures as symbolising the mouth of hell. However, the influence of the Industrial Revolution on Romantic painters is a side issue, almost an impertinence, when compared to its influence on human life. I needn’t remind you of how cruelly it degraded and exploited a mass of people for sixty or seventy years.

What was destructive was size. After about 1790 to 1800 there appeared the large foundries and mills which dehumanised life. Long before Carlyle and Karl Marx, Wordsworth had described the arrival of a night shift ‘that turns the multitude of dizzy wheels, Men, maidens, youths, Mothers and little children, boys and girls, Perpetual sacrifice.’

The terrible truth is that the rise in population did nearly ruin us. It struck a blow at civilisation such as it hadn’t received since the barbarian invasions. First it produced the horrors of urban poverty. It must have seemed—may still seem—insoluble; yet this doesn’t excuse the callousness with which prosperous people ignored the conditions of life among the poor on which to a large extent their prosperity depended, and this in spite of the many detailed and eloquent descriptions that were available to them. I need mention only two—Engels’s Conditions of the Working Classes in England, written in 1844, and the novels written by Dickens between 1840 and 1855. Everybody read Dickens. But his terrible descriptions of poverty had very little practical effect: partly because the problem was too big; partly because politicians were held in the intellectual prison of classical economics.

The images that fit Dickens are by the French illustrator Gustave Doré. He was originally a humorist; but the sight of London sobered him. His drawings were done in the 1870s, after Dickens’s death. But one can see that things hadn’t changed much. Perhaps it took an outsider to see London as it really was.

The images that fit Dickens are by the French illustrator Gustave Doré. He was originally a humorist; but the sight of London sobered him. His drawings were done in the 1870s, after Dickens’s death. But one can see that things hadn’t changed much. Perhaps it took an outsider to see London as it really was.

Degenerate architecture

At the beginning of this series I said that I thought one could tell more about a civilisation from its architecture that from anything else it leaves behind. Painting and literature depend largely on unpredictable individuals. But architecture is to some extent a communal art. However, I must admit that the public buildings on the nineteenth century are often lacking in style and conviction; and I believe that this is because the strongest creative impulse of the time didn’t go into the town halls or country houses, but into what was then thought of as engineering. In fact, all modern New York started with the Brooklyn Bridge.

In this series I have followed the ups and downs of civilisation historically, trying to discover results as well as causes; well, obviously I can’t do that any longer. We have no idea where we are going, and sweeping, confident articles of the future seem to me, intellectually, the most disreputable of all forms of utterance. The scientists who are best qualified to talk have kept their moths shut.

The incomprehensibility of our new cosmos seems to me, ultimately, to be the reason for the chaos of modern art. I know next to nothing about science, but I’ve spent my life trying to learn about art, and I am completely baffled by what is taking place today. I sometimes like what I see, but when I read modern critics I realise that my preferences are merely accidental.

Western civilisation has been a series of rebirths. Surely this should give us confidence in ourselves. I said at the beginning that it is lack of confidence, more than anything else, that kills a civilisation. We can destroy ourselves by cynicism and disillusion, just as effectively as by bombs. Fifty years ago W.B. Yeats, who was more like a man of genius than anyone I have ever known, wrote a famous poem.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

At which point a very obvious reflection crosses one’s mind: that the cathedrals were built to the glory of God, New York was built to the glory of mammon—money, gain, the new god of the nineteenth century. So many of the same human ingredients have gone into its construction that at a distance it does look rather like a celestial city. At a distance. Come closer and it’s not so good. Lots of squalor, and, in the luxury, something parasitical.