“Mental AIDS” is the collapse of a people’s immune system in the face of their enemies. Practically all whites throughout the West suffer from mental AIDS insofar as they are not defending their sacred lands against an invasion of millions of non-whites. However, some white nationalists get mad when hearing the expression “suicide” as a value judgment about the pathological passivity among present-day whites. Most nationalists speak, instead, of “homicide”: the Jews being the primary infection that infected the white soul.

But what if they are a secondary infection? After all, the white people contracted Christianity (HIV) in the 4th century, which after a long incubation period eventually developed into liberalism (AIDS) during the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Liberalism, or Neochristianity as I like to call it, weakened the West’s immune system. After Napoleon, Neochristians opened the door to the subversive tribe throughout continental Europe—Jews—: a “mental AIDS”-related opportunistic infection, such as pneumonia is an infection of the somatic equivalent of AIDS.

See the HIV link above. If Christianity and its secular offshoots are massively involved in the West’s darkest hour, and I cannot conceive a biggest blunder than emancipating the Jew, why not start diagnosing the situation as “assisted suicide,” with the Jew only being too happy to comply the deranged Neochristian’s will to bring about his own death?

I am not alone in this apparently wild opinion. Below, my abridgment of Tom Sunic’s “Race and Religion: Awkward Friends of the White Man,” published in three parts at The Occidental Observer:

♣

Regardless how much empirical artillery one can muster in defence of the uniqueness of the White gene pool, and regardless of how many facts one can enumerate that point to diverse intellectual achievements of different races, no such evidence will elicit social or academic approval. In fact, if loudly uttered, the evidence may be considered a felony in some Western countries. In our so-called free and secular society, new religions, such as the religion of racial promiscuity and the theology of the free market have replaced the old Christian belief system. Only when these new secular dogmas or political theologies start crumbling down—which may soon be the case—alternative views about race and the meaning of the sacred may appear.

Regardless how much empirical artillery one can muster in defence of the uniqueness of the White gene pool, and regardless of how many facts one can enumerate that point to diverse intellectual achievements of different races, no such evidence will elicit social or academic approval. In fact, if loudly uttered, the evidence may be considered a felony in some Western countries. In our so-called free and secular society, new religions, such as the religion of racial promiscuity and the theology of the free market have replaced the old Christian belief system. Only when these new secular dogmas or political theologies start crumbling down—which may soon be the case—alternative views about race and the meaning of the sacred may appear.

The historical irony is that it was not the Other, i.e. the non-White, who invented the arsenal of bashing the White man. It was the White man himself—both with his Christian atonement and now with his liberal expiation of the feelings of guilt.

Alain de Benoist writes that liberalism has been a racist system par excellence. In the late 19th century, it preached exclusive racism. Now, in the 21st century it preaches inclusive racism. By herding non European races from all over the world into a rootless a-racial and a-historical agnostic consumer society and by preaching ecumenical miscegenation, the West nonetheless holds its undisputed role of a truth maker—of course, this time around under the auspices of the self-hating, self-flagellating White male.

It must be stated that it was not the Colored, but the White man who had crafted the ideology of self-denial and the concomitant ideology of universal human rights, as well as the ideas of interracial promiscuity. Therefore, any modest scholarly argument suggesting proofs of racial inequality is untenable today. How can one persuasively argue about the existence of different races if the modern system lexically, conceptually, scientifically, ideologically, theologically, and last, but not least, judicially, forbids the slightest idea of race segregation—except when it evokes skin-deep exotic escapades into musical and culinary prowess of non-European races?

Most American White nationalists use Thomas Jefferson as their patron saint, frequently associating his name with “good old times” of the American Declaration of Independence. Those were the times when the White man was indeed in command of his destiny. The White founding fathers stated:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Yet the abstract words “all men” combined with the invocation of a deistic and distant “creator” had a specific significance in the mind of Enlightenment-groomed Jefferson. Two hundred years later, however, his words ring a different bell in the ears of a real Muslim Somali or a Catholic Cholo planning to move to the United States.

Wailing and whining that “Jefferson did not mean this; he meant that”—is a waste of time. The American Declaration bears witness to the classical cleavage between the former signifier and the modern signified which has become the subject of its own semantic sliding—with ominous consequences for Whites worldwide.

Contemporary geneticists and biologists are no less vulnerable than philosophers and sociologists to dominant political theologies. What was considered scientific during the first part of the 20th century in Europe and the United States by many prominent scholars writing about race is viewed today as preposterous and criminal. The dominant dogma idea of egalitarianism must give its final blessing in explaining or explaining away any scientific discovery.

Although the field of the former Soviet social sciences is considered today as quackery, its egalitarian, Marxist residue of omnipotent inheritance of acquired characteristics is religiously pursued by the post-Christian, neoliberal capitalist West. In layman’s terms, this means that the floodgates for mass immigration of non-Europeans must be kept wide open. Racial promiscuity and miscegenation must be enforced. It is science! It is the law!

As in the ex-Soviet Union, the dominant theology of egalitarianism and TV shows incessantly role-modeling interracial sex only accelerate the culture of mediocrity and the culture of death.

European and American history has been full of highly intelligent individuals endorsing abnormal religious and political beliefs. This is particularly true for many temporary White European and American left-leaning academics who, although showing high IQ, are narrow-minded, spineless individuals of no integrity, or race traitors of dubious character. Low IQ Cholos or affirmative action Blacks are just happy pawns in their conspiratorial and suicidal game.

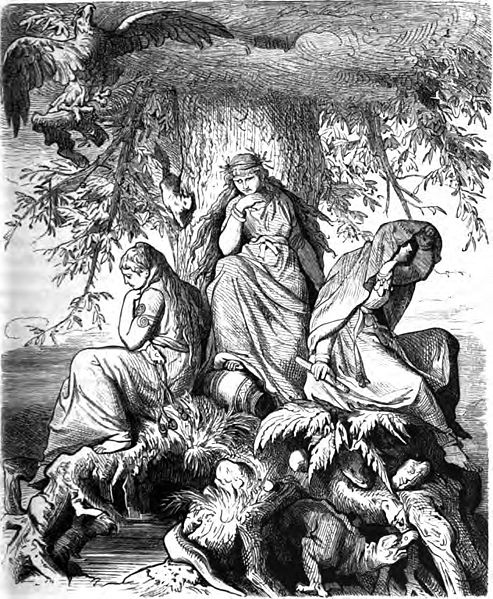

[White suicide]

The pristine, pastoral and puerile picture of the White race, so dearly longed for by modern White nationalists, is daily belied by permanent religious bickering, jealousy and character smearing within the White rank and file. Add to that murderous intra-White wars that have rocked Europe and America for centuries, one wonders whether the proverbial and much vaunted Aryan, Promethean, and Faustian man, is worthy of a better future.

Surely, the White man saved Greco-Roman Europe from the Levantine Hannibal’s incursion, which nearly resulted in a catastrophe in 216 b.c. at Cannae, in southern Italy. The White man also stopped Attila’s Hunic hordes on the Catalaunian Fields in France in 451 a.d. The grandfather of Charlemagne, Charles Martel, defeated Arab predators near Tours, in France in 732. One thousand years later in 1717, a short and slim Italo-French Catholic hero, Prince Eugene of Savoy, finally removed the Islamic threat from the Balkans.

But… the power of the newly discovered universal religion and the expectancy of the “end of history,” later to be followed by bizarre beliefs in “global democracy,” often eclipsed racial awareness among Whites. As a rule, when White princes ran out of Muslim or Jewish infidels—they began whacking each other in the name of their Semitic deities or latter day democracies. The 6’4” tall Charlemagne, in the name of his anticipated Christian bliss, went on the killing spree against his fellow pagan Germans. In 782 a.d. he decapitated several thousand of the finest crop of Nordic Saxons, thereby earning himself a saintly name of the “butcher of the Saxons” (Sachsenschlächter).

[I wish that Sunic had mentioned how Julius Caesar ordered the massacre of the 40,000 inhabitants of Avaricum during the Gaul wars; how this monster destroyed 800 towns and enslaved millions of Celts; how “hundreds of thousands of blond, blue-eyed Celtic girls were marched south to be pawed by Semitic flesh merchants” in Rome’s slave markets. Also, in 408 a.d. the Romans, in all the Italian cities, butchered the wives and children of their German allies—60,000 of them.]

And on and on the story goes with true Christian or true democracy believers. No Jews, no Arabs, no communists have done so much damage to the White gene pool as Whites themselves. The Thirty Years War (1617–1647) fought amidst European Christians with utmost savagery, wiped out two thirds of the finest German racial stock, over 6 million people. The crazed papist Croatian mercenaries, under Wallenstein’s command, considered it a Royal and Catholic duty to kill off Lutherans, a dark period so well described by the great German poet and dramatist Friedrich Schiller. Even today in Europe the words “Croat years” (Kroatenjahre) are associated with the years of hunger and pestilence.

Nor did Oliver Cromwell’s troops—his Ironsides—during the English civil war, fare much better. Surely, as brave Puritans they did not drink, they did not whore, they did not gamble—they only specialized in skinning Irish Catholic peasants alive. Not only did their chief, the Nordic looking fanatic Cromwell consider himself more Jewish than the Jews—he actually brought them back from continental Europe, with far-reaching consequence both for England and America.

A slim, intelligent, Nordic looking, yet emotionally unstable manic depressive, William Sherman, burnt down Atlanta in 1864—probably in the hopes of fostering a better brand of democracy for the South. We may also probe some day into the paleocortex of the Nordic skull of an airborne Midwest Christian ex-choir boy, who joyfully dropped firebombs on German civilians during WWII.

The faith or the sacred?

No subject is so dangerous to address among White nationalists as the Christian religion. It is commendable to lambast Muslims, who are on the respectable hit-parade of the Axis of Evil. Jews also come in handy in a wholesale package of evil, which needs to be expiated—at least occasionally. But any critical examination of Judeo-Christian intolerance is viewed with suspicion and usually attributed to distinct groups of White people, such as agnostics or modern day self-proclaimed pagans.

Why did the White man accept the Semitic spiritual baggage of Christianity even though it did not quite fit with his racial-spiritual endowments? The unavoidable racialist thinker Hans Günther—a man of staggering erudition and knowledgeable not only of the laws of heredity, but also of comparative religions—reminds us that the submissive and slavish relation of man to God is especially characteristic of Semitic peoples. In his important little book, The Religious Attitudes of the Indo-Europeans, he teaches us about the main aspects of racial psychology of old Europeans. We also learn that Yahweh is a merciless totalitarian god who must be revered—and feared.

The messianic, chiliastic, or “communistic” mindset was unknown among ancient Europeans. They could not care less which gods other races, other tribes or other peoples believed in. Wars that they fought against the adversary were bloody, but they did not have the goal of converting the adversary and imposing on him the beliefs contrary to his racial heritage. Homer’s epic The Iliad is the best example. The self-serving, yet truly racist liberal-communistic endeavour, to wage “final and just war” in order to “make the world safe for democracy,” was something inconceivable for ancient Europeans.

A German-British racialist author of the early 20th century, Houston Stewart Chamberlain in his The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century writes that “a final judgment shows the intellectual renaissance to be the work of Race in opposition to the universal Church which knows no Race” (p. 326). Unlike Christianity, which preaches individual salvation, for ancient Europeans life can only have a meaning within the in-group—their tribe, their polis, or their civitas. Outside those social structures, life means nothing.

In the 1st century, words of far-reaching consequence for all Whites were pronounced by a Jewish heretic, the Apostle St. Paul, to the people of Galatia, an area in Asia Minor once populated by the Gauls (i.e., Celts). Galatia was then well underway to become a case study of multicultural debauchery—similar to today’s Los Angeles:

“You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.” (Galatians 3:28).

Christianity became thus a Universalist religion with a special mission to transform the Other into the Same. The seeds of egalitarianism—albeit on the religious, not yet on the secular level—were sown.

Although Christian Churches never publicly endorsed racial miscegenation, they did not endorse racial segregation either. This was true for the Catholic Church and its flock, as observed by the early French sociologist and racialist Gustave Le Bon. Consequently, Catholic Spaniards of White racial stock in Latin America could not halt decadence and debauchery in their new homelands as WASPs in North America did.

Later, in 1938, in light of eugenic and racial laws adopted not only in Germany and Italy, but also in other European countries and many states in America, Pope Pius XI made his famous statement: “It is forgotten that mankind is one large and overwhelming Catholic race.” This statement was to become part of his planned encyclical under the name The Unity of the Human Race.

“The unity of the human race”, as noble as these words may sound, is a highly abstract concept. On a secular level communist and liberal intellectuals constantly toy with it—in order to suppress real tribes, real nations, real peoples and their real racial uniqueness.

The folly of the compound noun: “anti-Semitism”

Civil religions also have their holy shrines, their holy relics, their pontiffs, their canons, their promises and their menaces. Failure to believe in them—or failure to at least pretend to believe in them—results, as a legal scholar of Catholic persuasion, Carl Schmitt wrote, in a heretic’s removal from the category of human beings. Among new civil religions one could enumerate the religion of multiculturalism, the religion of antifascism, the religion of the Holocaust, and the religion of economic progress.

Many Whites make a fundamental mistake when they portray new civil religions as part of an organized conspiracy of a small number of wicked people. In essence, civil religions are just secular transpositions of the Judeo-Christian monotheist mindset which, when combined with an inborn sense of tolerance and congenial naïveté of the White people, makes them susceptible to their enchanting effects.

As a result of semantic sliding of political concepts, the Jewish-born thinker and the father of the secular religion of communism, Karl Marx, would likely be charged today with “anti-Semitism” or the “incitement to racial hatred.” Leftist scholars usually do not wish to subject his little booklet, On the Jewish Question (1844) to critical analysis. Consider the following:

The Jew has emancipated himself in a Jewish manner, not only because he has acquired financial power, but also because, through him and also apart from him, money has become a world power and the practical Jewish spirit has become the practical spirit of the Christian nations. The Jews have emancipated themselves insofar as the Christians have become Jews.

Of particular significance is Marx’ last sentence “insofar as the Christians have become Jews.” In fact the White man has “jewified” himself by embracing the fundaments of the Jewish belief system, which, paradoxically, he uses now in criticizing Jews.

Christian anti-Semitism can be described, therefore, as a peculiar form of neurosis. Christian anti-Semites resent the Jews while mimicking the framework of resentment borrowed from Jews. Accordingly, even the Jewish god Yahweh was destined to become the anti-Semitic God of White Christians! In the name of this God, persecutions against Jews were conducted by White non-Jews. Simply put, the White non-Jew has been denying for centuries to the Jew his self-appointed “otherness” i.e. his uniqueness and his self-chosenness, while desperately striving to re-appropriate that same Jewish otherness and that same uniqueness, be it in the acceptance of Biblical tales, be it the espousal of the concept of linear time, be it in the belief of the end of history.

To face up to the purported bad sides of Judaism by using Christian tools, is futile. This is the argument of the German philosopher Eugen Dühring, who notes that “Christianity is an offshoot of Judaism” and “a Christian, when he rightfully comprehends himself as such, cannot be a serious and complete anti-Semite.” (Die Judenfrage als Frage des Rassencharakters, 1901). Dühring was a prominent German socialist philosopher, contemporary, but also a foe of Marx. Like most German socialist thinkers of the late 19th century he was an anti-Semite, in so far as he saw in the Jewry the incarnation of capitalism. Dühring notes that “historical Christianity, when observed in its true spirit, and all things considered, has been a backlash within and against Judaism, but it has also emerged from it and to some extent in its fashion.” (p. 25-26).

What German geneticists and anthropologists, such as Fritz Lenz, Hans Günther, Erwin Baur, Eugen Fischer and thousands of other scholars wrote about Jews had already been written and discussed—albeit from a philosophical, artistic and literary point of view—by thousands of European writers, poets and artists. From the ancient Roman thinker Tacitus to the English writer William Shakespeare, from the ancient Roman thinker Seneca, to the French novelist and satirist, L. Ferdinand Céline, one encounters in the prose of countless European authors occasional and not so occasional critical remarks about the Jewish character—remarks that could easily be called today anti-Semitic. Should these “anti-Semitic” authors, novelists, or poets be called insane? If so, then the entire European cultural heritage must be banned and labeled insane.

Excluding the Jew, while using his theological and ideological concepts is a form of latent phobia among Whites, of which Jews are very well aware of. Criticizing a strong Jewish influence in Western societies on the one hand, while embracing Jewish religious and secular prophets on the other, will lead to further tensions and only enhance the Jewish sense of self-chosenness and their timeless victimhood. In turn, this will only give rise to more anti-Jewish hatred with tragic consequences for all. The prime culprits are not Jews or Whites, but rather a civil religion of egalitarianism with its postmodern offshoots of universalism and multiculturalism.

The issue that needs to be addressed is why Whites, for two thousand years, have adhered to an alien, out-group, non-European conceptualization of the world.