interview – 5

Remember, there are ten episodes of this interview. This is the fifth.

At the beginning, Joel Webb quotes a text that blames only Judaism for liberalism. I call this self-righteous monocausalism, since it’s obvious that Christians are the biggest culprits (even early Church Fathers criticized Jews for their selective compassion, saying it wasn’t universalist but ethnocentric). As always, this pair seems to have no idea that the doctrines of the religion they profess have axiological consequences.

Later, Nick Fuentes says he believes in the historicity of Christian child sacrifices by Jews in the Middle Ages: something I don’t believe was historical. But Fuentes is right to criticize Napoleon for “emancipating” the Jews in Europe, something that didn’t happen in Russia (in my opinion, because the Russians didn’t go through a Renaissance and an Enlightenment that eventually transformed into neochristianity).

Webbon says: “All false religions lead to hell.”

That’s worse than any toxic message from Jews on Netflix or any other mass media outlet. I challenge anyone who doubts this to read my autobiography, Hojas Susurrantes, and still claim that the doctrine of eternal damnation wasn’t worse than Jewish subversion for the mental health of white men. The most ironic thing about this is that this pair ignores the fact that the core of the New Testament was written by Jews.

But shortly afterward, Fuentes said something very true: that the message of forgiveness is absent in the Old Testament, that it only appears in the Gospel (for example, with words like “forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing”), and that the Old Testament speaks more of exterminating enemy peoples.

What Fuentes ignores is that the Old Testament message is the right one if the Aryans were to adopt it (as Himmler’s SS did). This pair takes the out-group altruism inspired by Christianity for granted: it’s a morality that Christians don’t even question (nor do atheist neochristians).

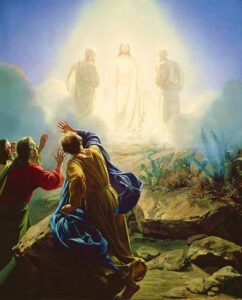

In this fifth instalment of the interview, we again note what Gaedhal once said: the dissident right is more primitive than liberal Christians, insofar as they wholesale ignore academic studies of the New Testament that differ from fundamentalist dogma (for example, Webbon speaks of the Transfiguration as if it were a historical event).

The blatant dishonesty comes soon after, when Webbon says, “Christian faith and reason are not at odds with one another.” If they were honest, these Christians would be familiar with the critical literature on New Testament historicity written since the time of Reimarus.

The blatant dishonesty comes soon after, when Webbon says, “Christian faith and reason are not at odds with one another.” If they were honest, these Christians would be familiar with the critical literature on New Testament historicity written since the time of Reimarus.

I make these comments from that series to show how lost American white nationalism is, even though Webbon isn’t one of them (Fuentes does consider himself a white nationalist). This episode proves it.

Later, Webbon asks Fuentes what transformed the healthy antisemitism of yesteryear into today’s pathological philosemitism. Fuentes blames modernism and liberalism. I wonder if Nick knows that we call liberalism “neochristianity” on this site? (new visitors who haven’t read our quotes from Tom Holland’s book should read them now).

Shortly after, Webbon says: “The engine of liberalism is egalitarianism: the complete flattening of every natural distinction…” Although Webbon mentions race and gender, he sees the speck in someone else’s eye but not his own. Following the destruction of the Greco-Roman world, it was Judeo-Christians who introduced egalitarianism into European culture. (Although both detest the word “Judeo-Christian”, they also ignore that early Christians were mostly Semites from the Roman Empire: so the term is legitimate.)

Note that, when they later discuss Protestant currents like dispensationalism, some factions of that current accept the salvation of Jews—that is, no post-mortem damnation for the chosen people. However, they don’t extend this courtesy to so-called “pagans” (those who refuse to worship the god of the Jews). How can this pair not realise that this type of doctrine will sooner or later develop a philosemite theology (not only Protestant, but also Catholic after the Second Vatican Council)?

Fuentes then says that the foundation of liberalism and modernity is the concept of the human psyche as a tabula rasa, a “blank slate”: that we are all born as persons, and therefore equal. He fails to realise that this belief was spawned by elemental Christian teachings: that, unlike animals, all humans are born with a “soul”, and that “God” doesn’t distinguish between “souls”.

Do you see why we call liberalism neochristianity? Later, they both agree that we must wait for the Jews to convert to Christianity and that, in the meantime, Jews have rights and shouldn’t be mistreated. Compare this to the Germans of the last century, who transvalued Christian values into values similar to those of Titus and Hadrian during Rome’s wars against Judea.

Do you finally understand what our slogan means?

Umwertuung Aller Werte!

Transvaluation of all values!