by Evropa Soberana

Eugenics is born

From the racial point of view, the effects of the French Revolution are detestable. With the aristocracy traditionally associated with the Nordic aspect, it was common for many individuals to be executed only because they had very Nordish features, even if they were not aristocrats!

Although the Revolution boasted of being a popular reaction against absolutism, sixty percent of the guillotined were simple French peasants. Such level of revolutionary hysteria was reached by the hand of unbalanced and decadent pseudo-intellectuals, belonging precisely to the high social classes, such as Rousseau, alienated and with illuminist pretensions, dazzled by the symbology of their lodges and financed by strange financial circles. A famished and illiterate plebs, elevated to the status of supreme judge, did the rest of the work.

Although the Revolution boasted of being a popular reaction against absolutism, sixty percent of the guillotined were simple French peasants. Such level of revolutionary hysteria was reached by the hand of unbalanced and decadent pseudo-intellectuals, belonging precisely to the high social classes, such as Rousseau, alienated and with illuminist pretensions, dazzled by the symbology of their lodges and financed by strange financial circles. A famished and illiterate plebs, elevated to the status of supreme judge, did the rest of the work.

In addition to the French Revolution and Napoleon, other processes marked the end of Christian hegemony: the Enlightenment, the American Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of Germany, Great Britain and the United States as great powers, with Russia waiting at the side.

This did not imply, in any way, an improvement of the European race. On the contrary: the race continued to degenerate because of wars and the assistance to the useless. It simply implied that this generation had fewer taboos when it came to expressing itself. Above all, it was the scientific advances and the recovery of the Greco-Roman legacy (as well as the translation of certain Eastern sacred texts of Indo-European origin) what started a more scientific worldview.

Eugenics, which was born in England, really became a mainstream issue and commonsense, fully supported by most of the scientific community that at that time was not coerced by politically correct interests.

It was also supported and by such notable characters as Harvard professor and famous scientist Louis Agassiz, the English philosopher Herbert Spencer [1], the French F.A. Gobineau, American President Woodrow Wilson, British economist J.M. Keynes, French writer Émile Zola, American tycoon W.K. Kellogg, Scottish anthropologist and anatomist Sir Arthur Keith, British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, famous American aviator Charles Lindberg, the Swedish composer Hugo Alfven and the British politician Sidney Webb.

All or almost all of the men that will be mentioned in this section—mostly English and American—were considered geniuses, laid the foundations of many modern scientific disciplines and were highly respected by the society of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Moreover, eugenics really was put into practice in countries considered advanced in the industrial, cultural, economic, technological and military sense, such as several states of the USA, Canada, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Switzerland and Japan.

We should not feel excessive sympathy for the social system of this era, dominated by voracious and heartless capitalism. The Industrial Revolution, which began in England spreading to Belgium, northern Germany, France, the United States and the entire West, uprooted millions of good-natured farmers from the healthy and quiet countryside, who were crowded into filthy working-class neighbourhoods, where they gradually degenerated and they became burned-out proletarians, resentful and without identity.

On top of it, the ruling class that benefited from the misery of these individuals allowed themselves the luxury of considering them inferior, while having tea with speculators and usurers. To a certain extent it is necessary to understand that this was the perfect breeding ground for the emergence of Bolshevism, and that the ruling classes of the time did not know how to provide it properly. Only the German Nazis, which I will deal with in the next section, finally had the keenness to reverse this process in a truly socialist way with their doctrine of Blut und Boden.

Another reason why I am partly glad that the eugenicists did not fully apply their policy is that the individuals mentioned here often based their selection on economic, social, cultural and productive criteria. Thus, they would not have hesitated to sterilise a tramp, perhaps even if such a tramp was not a ‘genetic homeless man’, but a worker who had bad luck and ended up in the street.

In short, they did not attempt to apply a biological criterion for the creation of a superior man, but a social criterion for the creation of a productive citizen. And the mass production of exemplary sheep without noble blood is something that does not inspire sympathy, as the goal of a true bio-policy should be the production of free and perfect human specimens physically, mentally and spiritually.

Even considering these unpleasant issues, it is unquestionable that thanks to the conditions enjoyed by the upper classes, a taste for classical literature and the absence of politically correct obstacles, science and philosophy advanced hand in hand thanks to very prepared and creative individuals who had all the time in the world to do some research.

The most alarming factor found by the first eugenicists was that, in the modern world, intelligence and fertility are inversely proportional to each other. That is to say, intelligent people have few children; they do not mate, which is a calamity. Conversely, stupid and weak folks tend to procreate prolifically, which doubles the calamity. This trend, already observable in the 19th century, continues to this day magnified as never before.

Sir Charles Darwin (1809-1882), English naturalist, explorer, rigorous and thorough scientist, and also a good writer and family man, famous for postulating the theory of evolution and natural selection.

Sir Charles Darwin (1809-1882), English naturalist, explorer, rigorous and thorough scientist, and also a good writer and family man, famous for postulating the theory of evolution and natural selection.

I find funny the Darwin case. Today, liberals quote him and mention him as if Darwin’s sole objective had been to stagger the Church, trying to make it ‘progressive’, when the only archetype that Darwin embodies is that of the scientist without prejudice.

Progressives who trash Darwin’s name should know that both Darwin and natural selection are anti-progressives. Darwin, like Nature, advocated the selection and survival of the most gifted. That beauty is the outcome of sexual selection is a phrase that largely offers us the quintessence of his mentality. His book On the Origin of Species has a revealing subtitle, very politically incorrect and very little known: The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

Progressives who trash Darwin’s name should know that both Darwin and natural selection are anti-progressives. Darwin, like Nature, advocated the selection and survival of the most gifted. That beauty is the outcome of sexual selection is a phrase that largely offers us the quintessence of his mentality. His book On the Origin of Species has a revealing subtitle, very politically incorrect and very little known: The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

Darwin, like every good scientist, did not care about the moral dilemmas and the taboos around the ‘art of looking good’. Darwin applauded the ‘fascist’, ‘anti-Semitic’ and ‘racist’ ideas of his cousin Galton as soon as he read them, while Galton was also decisively influenced by Darwin. We can conclude, therefore, that the current PC progressive-socio-democrats who try to put Darwin in their same bag have not read Darwin:

It is very true what you say about the higher races of men, when high enough, replacing & clearing off the lower races. In 500 years how the Anglo-Saxon race will have spread & exterminated whole nations; & in consequence how much the Human race, viewed as a unit, will have risen in rank. (Charles Darwin to Charles Kingsley, 6 February 1862).

At some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilised race will almost certainly exterminate, and replace, the savage races throughout the world… The break between man and his nearest allies will then be wider, for it will intervene between man in a more civilised state, as we may hope, even than the Caucasian, and some ape as low as a baboon, instead of as now between the negro or Australian [aborigine] and the gorilla. (Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, 1871).

I could show fight on natural selection having done and doing more for the progress of civilisation than you seem inclined to admit. Remember what risks the nations of Europe ran, not so many centuries ago of being overwhelmed by the Turks, and how ridiculous such an idea now is. The more civilised so-called Caucasian races have beaten the Turkish hollow in the struggle for existence. Looking to the world at no very distant date, what an endless number of the lower races will have been eliminated by the higher civilised races throughout the world. (Charles Darwin to William Graham, 3 July 1881).

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) barely needs an introduction. One of the most read philosophers of all time, and demonstrator of ‘how to philosophise by hammering’, there are many idiot nihilists, leftists or individualists who have tried to appropriate his legacy while a reading of Nietzsche reveals, without any doubt, a pre-Nazi, racist, anti-Semitic, anti-democratic, anti-anarchist and anti-communist mentality.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) barely needs an introduction. One of the most read philosophers of all time, and demonstrator of ‘how to philosophise by hammering’, there are many idiot nihilists, leftists or individualists who have tried to appropriate his legacy while a reading of Nietzsche reveals, without any doubt, a pre-Nazi, racist, anti-Semitic, anti-democratic, anti-anarchist and anti-communist mentality.

1.- My demand of the philosopher is well known: that he take his stand beyond good and evil and treat the illusion of moral judgment as beneath him.

2.- A first, tentative example: at all times morality has aimed to ‘improve’ men—this aim is above all what was called morality.

To call the taming of an animal its ‘improvement’ sounds almost like a joke to our ears. Whoever knows what goes on in kennels doubts that dogs are ‘improved’ there. They are weakened, they are made less harmful, and through the depressive effect of fear, through pain, through wounds, and through hunger, they become sickly beasts. It is no different with the tamed man whom the priest has ‘improved’.

In the early Middle Ages, when the church was indeed, above all, a kennel, the most perfect specimens of the ‘blond beast’ were hunted down everywhere; and the noble Teutons, for example, were ‘improved’.

But how did such an ‘improved’ Teuton look after he had been drawn into a monastery? Like a caricature of man, a miscarriage: he had become a ‘sinner’, he was stuck in a cage, tormented with all sorts of painful concepts. And there he lay, sick, miserable, hateful to himself, full of evil feelings against the impulses of his own life, full of suspicion against all that was still strong and happy. In short, a ‘Christian’…

3.- Let us consider the other method for ‘improving’ mankind, the method of breeding a particular race or type of man. The most magnificent example of this is furnished by Indian [Aryan] morality, sanctioned as religion in the form of ‘the law of Manu’. Here the objective is to breed no less than four races within the same society: one priestly, one warlike, one for trade and agriculture, and finally a race of servants, the Sudras.

Obviously, we are no longer dealing with animal tamers: a man that is a hundred times milder and more reasonable is the only one who could even conceive such a plan of breeding. One breathes a sigh of relief at leaving the Christian atmosphere of disease and dungeons for this healthier, higher, and wider world. How wretched is the New Testament compared to Manu, how foul it smells!

Yet this method also found it necessary to be terrible—not in the struggle against beasts, but against their equivalent—the ill-bred man, the mongrel man, the chandala. And again the breeder had no other means to fight against this large group of mongrel men than by making them sick and weak. Perhaps there is nothing that goes against our feelings more than these protective measures of Indian [Aryan] morality.

Manu himself says: ‘The chandalas are the fruit of adultery, incest, and rape (crimes that follow from the fundamental concept of breeding)’.

4.- These regulations are instructive enough: we encounter Aryan humanity at its purest and most primordial; we learn that the concept of ‘pure blood’ is very far from being a harmless concept. On the other hand, it becomes obvious in which people the chandala hatred against this Aryan ‘humaneness’ has become a religion, eternalized itself, and become genius—primarily in the Gospels, even more so in the Book of Enoch.

Christianity, sprung from Jewish roots and comprehensible only as a growth on this soil, represents the counter-movement to any morality of breeding, of race, privilege: it is the anti-Aryan religion par excellence. Christianity—the revaluation of all Aryan values, the victory of chandala values, the gospel preached to the poor and base, the general revolt of all the downtrodden, the wretched, the failures, the less favoured, against ‘race’: the undying chandala hatred is disguised as a religion of love. (Twilight of the Idols, section ‘The “Improvers” of Mankind’).

Clémence Royer (1830-1902), self-taught and French anarchist who wrote and lectured on feminism, economics, politics and science. She is best known for her translation of On the Origin of Species in French.

The data of the theory of natural selection leave us no doubt that the higher races have appeared gradually and that, therefore, under the law of progress, they are destined to replace the inferior races still in development, and do not mix or merge with them, at the risk of being absorbed by them by miscegenation, reducing the middle level of the species.

In short, human races are not separate species, but rather well marked and of very uneven varieties, and it must be thought twice before promoting political and civil equality in a country with a minority of Indo-Europeans and a majority of blacks or Mongols. (Preface to her translation of On the Origin of Species, 1862.)

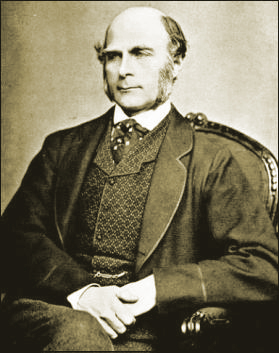

Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), Darwin’s cousin, anthropologist, geographer, explorer, inventor, meteorologist, statistician and English psychologist. Galton, impressed by the theories of natural selection and survival of the fittest observed by his cousin, was the one who coined the word Eugenics (‘good birth’, or ‘birth of the good’) around 1884.

Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), Darwin’s cousin, anthropologist, geographer, explorer, inventor, meteorologist, statistician and English psychologist. Galton, impressed by the theories of natural selection and survival of the fittest observed by his cousin, was the one who coined the word Eugenics (‘good birth’, or ‘birth of the good’) around 1884.

Galton advocated the prevention of the reproduction of morons, the mentally retarded and the insane—calling these measures ‘negative eugenics’ or limiting the growth of the worst—and granting certificates and economic funds to young men and women who were ‘suitable for civilisation’ so they could marry young and procreate an abundant offspring—‘positive eugenics’ or favouring the best.

Galton, a representative of a ruling Anglo-Saxon class that would remain healthy until 1939, wrote that blacks were inferior to whites and incapable of any civilisation, while Jews could only aspire to ‘parasitism’ within more gifted and capable nations.

Galton intended that eugenics (‘being well born’) become a religion, which would eventually replace Christianity. He accused Christianity for the fall of the Roman Empire; for having seriously damaged Western Civilisation by preaching pity and charity towards the useless and that ‘the weak will inherit the Earth’. He carried out an exhaustive, rigorous and scientific study of entire genealogies of illustrious characters, elaborating detailed statistics and finding—unsurprisingly—that genius is derived by inheritance and, therefore, from family.

Under his patronage the British Eugenics Society was founded in 1908, which would soon strengthen ties with similar groups in the United States.

I propose to show in this book that a man’s natural abilities are derived by inheritance, under exactly the same limitations as are the form and physical features of the whole organic world. Consequently, as it is easy, notwithstanding those limitations, to obtain by careful selection a permanent breed of dogs or horses gifted with peculiar powers of running, or of doing anything else, so it would be quite practicable to produce a highly-gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations. (Hereditary Genius, opening statement of the introductory chapter.)

What nature does blindly, slowly, and ruthlessly, man may do providently, quickly, and kindly. As it lies within his power, so it becomes his duty to work in that direction. The improvement of our stock seems to me one of the highest objects that we can reasonably attempt. (‘Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims’, 1904).

[Eugenics] must be recognized as a subject whose practical development deserves serious consideration. It must be introduced into the national conscience, like a new religion. It has, indeed, strong claims to become an orthodox religious, tenet of the future, for eugenics co-operate with the workings of nature by securing that humanity shall be represented by the fittest races (Ibid).

It is neither more nor less than that the development of our nature, under Darwin’s law of Natural Selection, has not yet over-taken the development of our religious civilisation (Memories of my Life).

I take Eugenics very seriously, feeling that its principles ought to become one of the dominant motives in a civilised nation, much as if they were one of its religious tenets. I have often expressed myself in this sense, and will conclude this book by briefly reiterating my views (Ibid.).

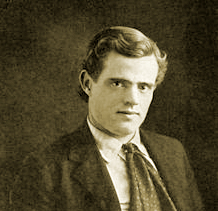

Jack London (1876-1903), famous American writer of socialist tendency but racist, patriot, an apologist of the Anglo-Saxon and Nietzschean civilisation.

Jack London (1876-1903), famous American writer of socialist tendency but racist, patriot, an apologist of the Anglo-Saxon and Nietzschean civilisation.

For a time he operated a cattle farm, where he became convinced that the farmers had been practicing eugenics since immemorial times.

I believe that the future human world belongs to eugenics, and will be determined by the practice of eugenics. (Letters, 376).

________

Note

[1] Herbert Spencer coined the famous phrase survival of the fittest in addition to launching the current of thought that posterity knows as ‘social Darwinism’.