Lebenskraft ! (10)

Dachau

Then I headed to Dachau, about 45 minutes from Munich. On the way I passed where the Gestapo had their offices. Here I am looking at the entrance and exit gates of the concentration camp:

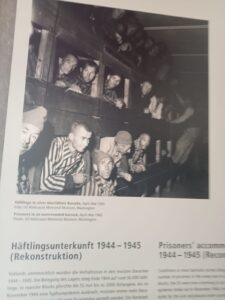

Previous generations of Germans weren’t as aggressively brainwashed as they are today. The person in charge of showing us the Dachau concentration camp, for example, had a mother who belonged to the Hitler Youth, and her father never talked about the war unless the beer got too much, she confessed. Nowadays, the System forces the adolescents to visit Dachau to indoctrinate them in anti-Nazi ideology, as we see in this picture I took:

The number of young people I saw in the camp was considerable! But in reality, Dachau wasn’t an extermination camp but a re-education camp for opponents of the Third Reich. It was a camp for males. Himmler was born very close to it, and when he came to power, he had the excellent idea of imprisoning the political opposition.

The camp operated from 1933 to 1945 and is now home to riot control units, which occupy many of Dachau’s buildings. Prisoners began arriving in 1933. Official figures put the number of detainees at 206,000 in the years the camp was active, and 42,000 who died there. The camp is huge: it covers 200 hectares and there is a plaque commemorating the ‘liberation’ perpetrated by the gringos in April 1945.

I am irritated to report that, on visiting the camp, the guide informed us that this month would be the 80th anniversary of the ‘liberation’ of Dachau, celebrated in a big way there.

In the 1930s there was a saying for dissidents, ‘Shut up if you don’t go to Dachau’. Nowadays people in power also incarcerate political dissidents, as evidenced by Joseph Walsh and Chris Gibbons serving a sentence of years and recently, also in England, twelve men were arrested for daring to celebrate Hitler’s birth, as an Englishman let us know today. The hypocrisy is so blatant that the Americans used Dachau for three years to imprison Germans!

This sort of thing, naturally, is not denounced by official guides unlike Himmler, who announced in a newspaper why Dachau had been opened:

In some of the photos in the museum we can see who was imprisoned. For example, a clergyman said in a sermon that it was legitimate to assassinate a tyrant (Hitler). The mayor of Vienna also ended up in Dachau. After all, in real life he behaved as Captain Georg von Trapp behaved in The Sound of Music: an exception, because the Austrian people in general opened their arms to the Führer.

The camp also received commies and political prisoners from all over Europe, especially Poles and Russians, but also French, Germans, Czechs and Republican Spaniards.

I love the German bureaucracy that ordered everything and scrupulously classified the type of prisoner, as long as there was a hierarchy among them. Some crimes against the state or the race were considered much more serious than others.

The blue triangle designated migrants; the black triangle designated consumers of degenerate culture and also those who married Jews. These measures couldn’t be implemented in a new ethnnostate because virtually all Westerners would have to be imprisoned, even some white nationalists, as Sebastian Ronin mocked in one of his cartoons!

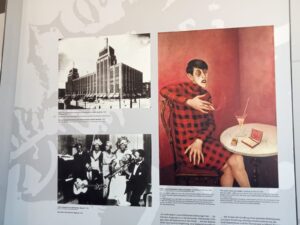

There were also colours for gypsies and political prisoners, red. Of course, consumers of degenerate culture fared much better in Dachau than, say, opponents of the regime, especially if they were Jews. But what does a consumer of degenerate culture mean? It should be obvious to today’s racialists that the Afro-American art is unfit for the Aryan spirit, as I saw on this museum poster:

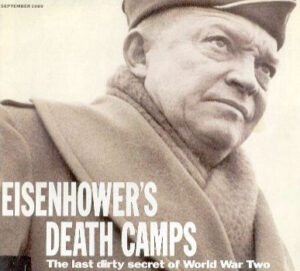

The chutzpa of the System never ceases to amaze me. In the conditions at Dachau, and remember that not every prisoner was treated equally but some were relatively well treated, just over forty thousand died according to official figures. Eisenhower murdered 800,000 Germans in real death camps!

Dachau was, as I said, a re-education camp where you could get out alive. In Eisenhower’s extermination camps no behaviour could save you: the object was to kill you for having been a National Socialist.

The barracks at Dachau were removed in the 1960s and now only the rows of poplar trees remain.

If you look closely at the picture above, in the background you can see the first memorial built for the ‘victims’ of the camp. It was not built by the Jews, but by Catholics: a church, built in 1964.

The church bells ring at 3 pm to commemorate the Catholic ‘saints’ and the ‘victims’ of Dachau. Behind it is a Carmelite monastery, built not long after. Next to it we can see the Lutheran church that was built later, commemorating the same thing.

The young people do voluntary service because the de-Nazification process never ends in Germany. Then the Orthodox Christians made their own monument: another propagandistic church. They even brought soil from Slavic soil because they didn’t want to build their church on German soil.

But you can also see the Jewish hand in Dachau in this memorial, as the first line is in Hebrew:

Then I saw the crematoria for those who died in the camp. According to the guide, who as I said her mother had been in the Hitler Youth, where this tree was, some of the prisoners were hanged:

It was strange to see beautiful women visiting the museum.

And a mixed couple was not to be missed.

The museum, the guided tours by guides who must be licensed by the German state, and all the culture and universities of Munich are a gigantic fraud. Munich, a city where only a few buildings are taller than the cathedral, is the publishing capital of Europe (only New York has more publishing houses), but what good is so much culture if they are incapable of publishing a book denouncing the Hellstorm Holocaust, like the one written by Tom Goodrich? The lie by omission is astronomical indeed, and the way the Establishment treats its authentic historians is shown by the following anecdote.

When Goodrich wrote Hellstorm he struggled to find a publisher in the US. So much so that, for a time, he was homeless (writers generally live from day to day, and a blow like not finding a publisher for the latest work can be fatal). Tom asked me not to reveal it as long as he lived.

But last year our friend passed away.