or

Why every decent person should become

an anti-Semite: First reason

Today I read “Stalin’s willing executioners: Jews as a hostile elite in the USSR” by Prof. Kevin MacDonald: a book-review of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century (Princeton University Press, 2004).

Since MacDonald’s magnificent review is 17,000 words, I decided to cut it by half. Endnotes can be read in the original article (no ellipsis added between unquoted paragraphs):

A persistent theme among critics of Jews—particularly those on the pre-World War II right—has been that the Bolshevik revolution was a Jewish revolution and that the Soviet Union was dominated by Jews. This theme appears in a wide range of writings, from Henry Ford’s International Jew, to published statements by a long list of British, French, and American political figures in the 1920s (Winston Churchill, Woodrow Wilson, and David Lloyd George), and, in its most extreme form, by Adolf Hitler, who wrote:

Now begins the last great revolution. By wresting political power for himself, the Jew casts off the few remaining shreds of disguise he still wears. The democratic plebeian Jew turns into the blood Jew and the tyrant of peoples. In a few years he will try to exterminate the national pillars of intelligence and, by robbing the peoples of their natural spiritual leadership, will make them ripe for the slavish lot of a permanent subjugation. The most terrible example of this is Russia.

Jewish involvement in the Communist elite of the USSR can be seen as a variation on an ancient theme in Jewish culture rather than a new one sprung from the special circumstances of the Bolshevik Revolution. Rather than being the willing agents of exploitative non-Jewish elites who were clearly separated from both the Jews and the people they ruled, Jews became an entrenched part of an exploitative and oppressive elite in which group boundaries were blurred. This blurring of boundaries was aided by four processes, all covered by Slezkine: shedding overt Jewish identities in favor of a veneer of international socialism in which Jewish identity and ethnic networking were relatively invisible; seeking lower-profile positions in order to de-emphasize Jewish preeminence (e.g., Trotsky); adopting Slavic names; and engaging in a limited amount of intermarriage with non-Jewish elites. Indeed, the “plethora of Jewish wives” among non-Jewish leaders doubtless heightened the Jewish atmosphere of the top levels of the Soviet government.

When Jews won the economic competition in early modern Poland, the result was that the great majority of Poles were reduced to the status of agricultural laborers supervised by Jewish estate managers in an economy in which trade, manufacturing, and artisanry were in large part controlled by Jews.

Slezkine does note that the rise of the Jews in the USSR came at the expense of the Germans as a Mercurian minority in Russia prior to the Revolution.

Or rather, the Russian Germans were to Russia what the German Jews were to Germany—only much more so. So fundamental were the German Mercurians to Russia’s view of itself that both their existence and their complete and abrupt disappearance have been routinely taken for granted (pp. 113–114).

The difference between the Jews and the Germans was that the Jews had a longstanding visceral antipathy, out of past historical grievances, both real and imagined. Vladimir Purishkevich, accused the Jews of “irreconcilable hatred of Russia and everything Russian.”

In this respect, the Germans were far more like the Overseas Chinese, in that they became an elite without having an aggressively hostile attitude toward the people and culture they administered and dominated economically. Thus when Jews achieved power in Russia, it was as a hostile elite with a deep sense of historic grievance. As a result, they became willing executioners of both the people and cultures they came to rule, including the Germans.

After the Revolution, not only were the Germans replaced, but there was active suppression of any remnants of the older order and their descendants.

* * *

Slezkine sees the United States as a Jewish promised land precisely because it is not defined tribally and “has no state-bearing natives” (p. 369). But the recasting of the United States as a “proposition nation” was importantly influenced by the triumph of several Jewish intellectual and political movements more than it was a natural and inevitable culmination of American history. These movements collectively delegitimized cultural currents of the early twentieth century whereby many Americans thought of themselves as members of a very successful ethnic group.

For example, the immigration restrictionists of the 1920s unabashedly asserted the right of European-derived peoples to the land they had conquered and settled. Americans of northern European descent in the United States thought of themselves as part of a cultural and ethnic heritage extending backward in time to the founding of the country, and writers like Madison Grant (The Passing of the Great Race) and Lothrop Stoddard (The Rising Tide of Color against White World Supremacy) had a large public following. At that time both academia and mainstream culture believed in the reality of race; that there were important differences between the races, including in intelligence and moral character; and that races naturally competed for land and other resources.

It is no stretch at all, however, to show that Jews have achieved a preeminent position in Europe and America, and Slezkine provides us with statistics of Jewish domination only dimly hinted at in the following examples from Europe in the late nineteenth century to the rise of National Socialism. Austria: All but one bank in fin de siècle Vienna was administered by Jews, and Jews constituted 70% of the stock exchange council; Hungary: between 50 and 90 percent of all industry was controlled by Jewish banking families, and 71% of the most wealthy taxpayers were Jews; Germany: Jews were overrepresented among the economic elite by a factor of 33. Similar massive overrepresentation was also to be found in educational attainment and among professionals (e.g., Jews constituted 62% of the lawyers in Vienna in 1900, 25% in Prussia in 1925, 34% in Poland, and 51% in Hungary). Indeed,

the universities, “free” professions, salons, coffeehouses, concert halls, and art galleries in Berlin, Vienna, and Budapest became so heavily Jewish that liberalism and Jewishness became almost indistinguishable (p. 63).

Slezkine documents the well-known fact that, as Moritz Goldstein famously noted in 1912, “We Jews administer the spiritual possessions of Germany.” However, he regards Jewish cultural dominance, not only in Germany but throughout Eastern Europe and Austria, as completely benign: “The secular Jews’ love of Goethe, Schiller, and the other Pushkins—as well as the various northern forests they represented—was sincere and tender” (p. 68).

But the Germans, from Wagner to von Treitschke to Chamberlain and Hitler, didn’t see it that way. For example, Heinrich von Treitschke, a prominent nineteenth-century German intellectual, complained of Heine’s “mocking German humiliation and disgrace following the Napoleonic wars” and Heine’s having “no sense of shame, loyalty, truthfulness, or reverence.” Nor does he mention von Treitschke’s comment that “what Jewish journalists write in mockery and satirical remarks against Christianity is downright revolting”; “about the shortcomings of the Germans [or] French, everybody could freely say the worst things; but if somebody dared to speak in just and moderate terms about some undeniable weakness of the Jewish character, he was immediately branded as a barbarian and religious persecutor by nearly all of the newspapers.”

The main weapons Jews used against national cultures were two quintessentially modern ideologies, Marxism and Freudianism, “both [of which] countered nationalism’s quaint tribalism with a modern (scientific) path to wholeness” (p. 80). Slezkine correctly views both of these as Jewish ideologies functioning as organized religions, with sacred texts promising deliverance from earthly travail. While most of his book recounts the emergence of a Jewish elite under the banner of Marxism in the Soviet Union, his comments on psychoanalysis bear mentioning. Psychoanalysis “moved to the United States to reinforce democratic citizenship with a much-needed new prop…. In America, where nationwide tribal metaphors could not rely on theories of biological descent, Freudianism came in very handy indeed” by erecting the “Explicitly Therapeutic State” (pp. 79–80).

[Chechar’s note: See, e.g., my own critique of the therapeutic state in Spanish: here]

The establishment of the Explicitly Therapeutic State was much aided by yet another Jewish intellectual movement, the Frankfurt School, which combined psychoanalysis and Marxism. The result was a culture of critique which fundamentally aimed not only at delegitimizing the older American culture, but even attempted to alter or obliterate human nature itself: “The statistical connection between ‘the Jewish question’ and the hope for a new species of mankind seems fairly strong” (p. 90).

And when people don’t cooperate in becoming a new species, there’s always murder. Slezkine describes Walter Benjamin, an icon of the Frankfurt School and darling of the current crop of postmodern intellectuals, “with glasses on his nose, autumn in his soul and vicarious murder in his heart” (p. 216), a comment that illustrates the fine line between murder and cultural criticism, especially when engaged in by ethnic outsiders. Indeed, on another occasion, Benjamin stated, “Hatred and [the] spirit of sacrifice… are nourished by the image of enslaved ancestors rather than that of liberated grandchildren.” Although Slezkine downplays this aspect of Jewish motivation, Jews’ lachrymose perceptions of their history—their images of enslaved ancestors—were potent motivators of the hatred unleashed by the upheavals of the twentieth century.

Slezkine is entirely correct that Marxism, psychoanalysis, and the Frankfurt School were fundamentally Jewish intellectual movements. However, he fails to provide anything like a detailed account of how these ideologies served specifically Jewish interests, most generally in combating anti-Semitism and subverting ethnic identification among Europeans. Indeed, a major premise of his treatment is that Jewish radicals were not Jews at all.

* * *

In both the Soviet Union and Poland, Communism was seen as opposing anti-Semitism. In marked contrast, during the 1930s the Polish government enacted policies which excluded Jews from public-sector employment, established quotas on Jewish representation in universities and the professions, and organized boycotts of Jewish businesses and artisans. Clearly, Jews perceived Communism as good for Jews, and indeed a major contribution of Slezkine’s book is to document that Communism was good for Jews: It was a movement that never threatened Jewish group continuity, and it held the promise of Jewish power and influence and the end of state-sponsored anti-Semitism. And when this group achieved power in Poland after World War II, they liquidated the Polish nationalist movement, outlawed anti-Semitism, and established Jewish cultural and economic institutions.

As Slezkine himself notes, Jews were the only group that was not criticized by the revolutionary movement (p. 157), even though most Russians, and especially the lower classes whose cause they were supposedly championing, had very negative attitudes toward Jews. When, in 1915, Maxim Gorky, a strong philosemite, published a survey of Russian attitudes toward Jews, the most common response was typified by the comment that “the congenital, cruel, and consistent egoism of the Jews is everywhere victorious over the good-natured, uncultured, trusting Russian peasant or merchant” (p. 159). There were concerns that all of Russia would pass into Jewish hands and that Russians would become slaves of the Jews.

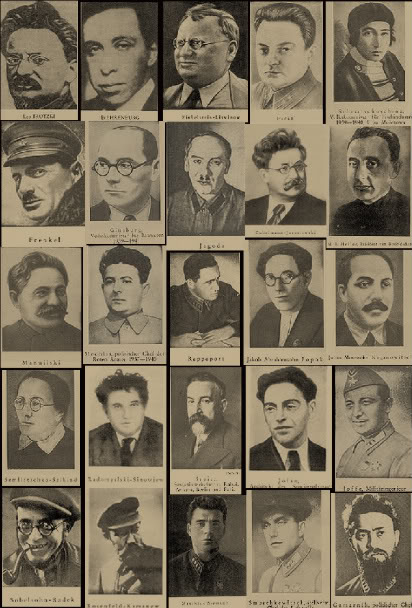

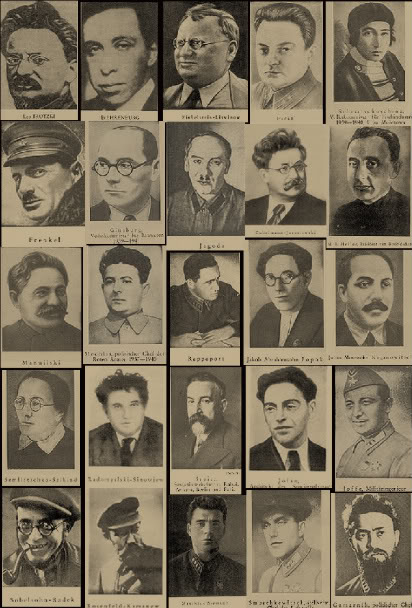

BOLSHEVISM AS A JEWISH REVOLUTION

But if Jews dominated radical and revolutionary organizations, they were immeasurably aided by philosemites like Gorky who, in Albert Lindemann’s term, were “jewified non-Jews” — “a term, freed of its ugly connotations, [that] might be used to underline an often overlooked point: Even in Russia there were some non-Jews, whether Bolsheviks or not, who respected Jews, praised them abundantly, imitated them, cared about their welfare, and established intimate friendships or romantic liaisons with them.” (As noted above, many of the non-Jewish elite in the USSR had Jewish wives.) What united the Jews and philosemites was their hatred for what Lenin (who had a Jewish grandfather) called “the thick-skulled, boorish, inert, and bearishly savage Russian or Ukrainian peasant” — the same peasant Gorky described as “savage, somnolent, and glued to his pile of manure” (p. 163). It was attitudes like these that created the climate that justified the slaughter of many millions of peasants under the new regime. Philosemites continued to be common among the non-Jewish elite in the USSR, even in the 1950s, when Jews began to be targeted as Jews.

But if Jews dominated radical and revolutionary organizations, they were immeasurably aided by philosemites like Gorky who, in Albert Lindemann’s term, were “jewified non-Jews” — “a term, freed of its ugly connotations, [that] might be used to underline an often overlooked point: Even in Russia there were some non-Jews, whether Bolsheviks or not, who respected Jews, praised them abundantly, imitated them, cared about their welfare, and established intimate friendships or romantic liaisons with them.” (As noted above, many of the non-Jewish elite in the USSR had Jewish wives.) What united the Jews and philosemites was their hatred for what Lenin (who had a Jewish grandfather) called “the thick-skulled, boorish, inert, and bearishly savage Russian or Ukrainian peasant” — the same peasant Gorky described as “savage, somnolent, and glued to his pile of manure” (p. 163). It was attitudes like these that created the climate that justified the slaughter of many millions of peasants under the new regime. Philosemites continued to be common among the non-Jewish elite in the USSR, even in the 1950s, when Jews began to be targeted as Jews.

Gorky’s love for the Jews was boundless. Despite the important role of Jews among the Bolsheviks, most Jews were not Bolsheviks before the revolution. However, Jews were prominent among the Bolsheviks, and once the revolution was under way, the vast majority of Russian Jews became sympathizers and active participants. Jews were particularly visible in the cities and as leaders in the army and in the revolutionary councils and committees. For example, there were 23 Jews among the 62 Bolsheviks in the All-Russian Central Executive Committee elected at the Second Congress of Soviets in October, 1917. Jews were the leaders of the movement, and to a great extent they were its public face. Slezkine quotes historian Mikhail Beizer who notes, commenting on the situation in Leningrad, that “Jewish names were constantly popping up in newspapers. Jews spoke relatively more often than others at rallies, conferences, and meetings of all kinds.”

In general, Jews were deployed in supervisory positions rather than positions that placed them in physical danger. In a Politburo meeting of April 18, 1919, Trotsky urged that Jews be redeployed because there were relatively few Jews in frontline combat units, while Jews constituted a “vast percentage” of the Cheka at the front and in the Executive Committees at the front and at the rear. This pattern had caused “chauvinist agitation” in the Red Army (p. 187).

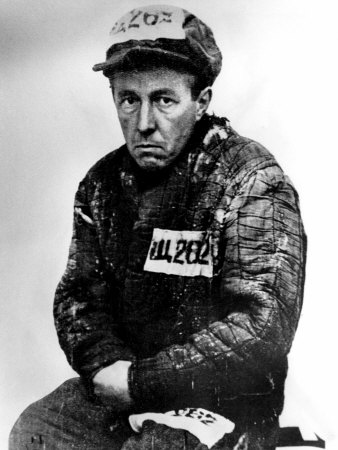

Jewish representation at the top levels of the Cheka and OGPU (the acronyms by which the secret police was known in different periods) has often been the focus of those stressing Jewish involvement in the revolution and its aftermath. Slezkine provides statistics on Jewish overrepresentation in these organizations, especially in supervisory roles, and agrees with Leonard Schapiro’s comment that “anyone who had the misfortune to fall into the hands of the Cheka stood a very good chance of finding himself confronted with and possibly shot by a Jewish investigator” (p. 177). During the 1930s the secret police, then known as the NKVD, “was one of the most Jewish of all Soviet institutions” (p. 254), with 42 of its 111 top officials being Jewish. At this time 12 of the 20 NKVD directorates were headed by ethnic Jews, including those in charge of state security, police, labor camps, and resettlement (i.e., deportation). The Gulag was headed by ethnic Jews from its beginning in 1930 until the end of 1938, a period that encompasses the worst excesses of the Great Terror. They were, in Slezkine’s words, “Stalin’s willing executioners” (p. 103).

The Bolsheviks continued to apologize for Jewish overrepresentation until the topic became taboo in the 1930s. And it was not until the late 1930s that there was a rise in visibility and assertiveness of “anti-Semites, ethnic nationalists, and advocates of proportional representation” (p. 188). By this time the worst of the slaughters in the Gulag, the purges, and the contrived famines had been completed.

The prominence of Jews in the Revolution and its aftermath was not lost on participants on both sides, including influential figures such as Winston Churchill, who wrote that the role of Jews in the revolution “is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others.” Slezkine highlights similar comments in a book published in 1927 by V. V. Shulgin, a Russian nationalist, who experienced firsthand the murderous acts of the Bolsheviks in his native Kiev in 1919:

We do not like the fact that this whole terrible thing was done on the Russian back and that it has cost us unutterable losses. We do not like the fact that you, Jews, a relatively small group within the Russian population, participated in this vile deed out of all proportion to your numbers (p. 181; italics in original).

Slezkine does not disagree with this assessment, but argues that Jews were hardly the only revolutionaries (p. 180). This is certainly true, but does not affect my argument that Jewish involvement was a necessary condition, not merely a sufficient condition, for the success of the Bolshevik Revolution and its aftermath. Slezkine’s argument clearly supports the Jews-as-necessary-condition claim, especially because of his emphasis on the leadership role of Jews.

However, the claim that Jewish involvement was a necessary condition is itself an understatement because, as Shulgin noted, the effectiveness of Jewish revolutionaries was far out of proportion to the number of Jews. A claim that a group constituting a large proportion of the population was necessary to the success of a movement would be unexceptional. But the critical importance of Jews occurred even though Jews constituted less than 5% of the Russian population around the time of the Revolution, and they were much less represented in the major urban areas of Moscow and Leningrad prior to the Revolution because they were prevented from living there by the Pale of Settlement laws. Slezkine is correct that Jews were not the only revolutionaries, but his point only underscores the importance of philosemitism and other alliances Jews typically must make in Diaspora situations in order to advance their perceived interests.

In 1923, several Jewish intellectuals published a collection of essays admitting the “bitter sin” of Jewish complicity in the crimes of the Revolution. In the words of a contributor, I. L. Bikerman, “it goes without saying that not all Jews are Bolsheviks and not all Bolsheviks are Jews, but what is equally obvious is that disproportionate and immeasurably fervent Jewish participation in the torment of half-dead Russia by the Bolsheviks” (p. 183). Many of the commentators on Jewish Bolsheviks noted the “transformation” of Jews: In the words of another Jewish commentator, G. A. Landau, “cruelty, sadism, and violence had seemed alien to a nation so far removed from physical activity.” And another Jewish commentator, Ia. A Bromberg, noted that:

the formerly oppressed lover of liberty had turned into a tyrant of “unheard-of-despotic arbitrariness”… The convinced and unconditional opponent of the death penalty not just for political crimes but for the most heinous offenses, who could not, as it were, watch a chicken being killed, has been transformed outwardly into a leather-clad person with a revolver and, in fact, lost all human likeness (pp. 183–184).

This psychological “transformation” of Russian Jews was probably not all that surprising to the Russians themselves, given Gorky’s finding that Russians prior to the Revolution saw Jews as possessed of “cruel egoism” and that they were concerned about becoming slaves of the Jews. Gorky himself remained a philosemite to the end, despite the prominent Jewish role in the murder of approximately twenty million of his ethnic kin, but after the Revolution he commented that “the reason for the current anti-Semitism in Russia is the tactlessness of the Jewish Bolsheviks. The Jewish Bolsheviks, not all of them but some irresponsible boys, are taking part in the defiling of the holy sites of the Russian people. They have turned churches into movie theaters and reading rooms without considering the feelings of the Russian people.” However, Gorky did not blame the Jews for this: “The fact that the Bolsheviks sent the Jews, the helpless and irresponsible Jewish youths, to do these things, does smack of provocation, of course. But the Jews should have refrained” (p. 186).

Those who carried out the mass murder and dispossession of the Russian peasants saw themselves, at least in their public pronouncements, as doing what was necessary in pursuit of the greater good. This was the official view not only of the Soviet Union, where Jews formed a dominant elite, but also was the “more or less official view” among Jewish intellectuals in the United States (p. 215) and elsewhere.

THE THREE GREAT JEWISH MIGRATIONS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Slezkine’s last and longest chapter describes the three great Jewish migrations of the twentieth century—to Israel, to America, and to the urban centers of the Soviet Union. Slezkine perceives all three through the lens of heroic Jewish self-perception. He sees the United States as a Jewish utopia precisely because it had only a “vestigial establishment tribalism” (p. 209) that could not long inhibit Jewish ascendancy:

The United States stood for unabashed Mercurianism, nontribal statehood, and the supreme sovereignty of capitalism and professionalism. It was—rhetorically—a collection of homines rationalistici artificiales, a nation of strangers held together by a common celebration of separateness (individualism) and rootlessness (immigration) (p. 207).

It was the only modern state “…in which a Jew could be an equal citizen and a Jew at the same time. ‘America’ offered full membership without complete assimilation. Indeed, it seemed to require an affiliation with a subnational community as a condition of full membership in the political nation” (p. 207). Slezkine sees post-World War II America as a Jewish utopia but seems only dimly aware that Jews to a great extent created their own utopia in the U.S. by undermining nativist sentiments that were common at least until after World War II. Slezkine emphasizes the Jewish role in institutionalizing the therapeutic state, but sees it as completely benign, rather than an aspect of the “culture of critique” that undermined the ethnic identities of white Americans: “By bringing Freudianism to America and by adopting it, briefly, as a salvation religion, [Jews] made themselves more American while making America more therapeutic” (p. 319). There is little discussion of the main anti-nativist intellectual movements, all of which were dominated by ethnically conscious Jews: Boasian anthropology, Horace Kallen and the development of the theory of America as a “proposition nation,” and the Frankfurt School which combined psychoanalysis and Marxism into a devastating weapon against the ethnic consciousness of white Americans. Nor does he discuss the role of Jewish activist organizations in altering the ethnic balance of the United States by promoting large-scale immigration from around the world.

But Slezkine spends most of his energy by far in providing a fascinating chronicle of the Jewish rise to elite status in all areas of Soviet society—culture, the universities, professional occupations, the media, and government. In all cases, Jewish overrepresentation was most apparent at the pinnacles of success and influence. To take just the area of culture, Jews were highly visible as avant-garde artists, formalist theorists, polemicists, moviemakers, and poets. They were “among the most exuberant crusaders against ‘bourgeois’ habits during the Great Transformation; the most disciplined advocates of socialist realism during the ‘Great Retreat’ (from revolutionary internationalism); and the most passionate prophets of faith, hope, and combat during the Great Patriotic War against the Nazis” (p. 225). And, as their critics noticed, Jews were involved in anti-Christian propaganda. Mikhail Bulgakov, a Russian writer, noticed that the publishers of Godless magazine were Jews; he was “stunned” to find that Christ was portrayed as “a scoundrel and a cheat. It is not hard to see whose work it is. This crime is immeasurable” (p. 244).

* * *

Some of the juxtapositions are striking and seemingly intentional. On p. 230, Lev Kopelev is quoted on the need for firmness in confiscating the property of the Ukrainian peasants. Kopelev, who witnessed the famine that killed seven to ten million peasants, stated, “You mustn’t give in to debilitating pity. We are the agents of historical necessity. We are fulfilling our revolutionary duty. We are procuring grain for our socialist Fatherland. For the Five-Year Plan.” On the next page, Slezkine describes the life of the largely Jewish elite in Moscow and Leningrad, where they attended the theater, sent their children to the best schools, had peasant women for nannies, spent weekends at pleasant dachas, and vacationed at the Black Sea.

Slezkine describes the NKVD as “one of the most Jewish of all Soviet institutions” and recounts the Jewish leadership of the Great Terror of the 1930s (pp. 254 and 255). On p. 256, he writes that in 1937 the prototypical Jew who moved from the Pale of Settlement to Moscow to man elite positions in the Soviet state “probably would have been living in elite housing in downtown Moscow…with access to special stores, a house in the country (dacha), and a live-in peasant nanny or maid…” (p. 256), but the reader is left to his own imagination to visualize the horrors of the Ukrainian famine and the liquidation of the Kulaks.

As Slezkine notes, most of the Soviet elite were not Jews, but Jews were far overrepresented among the elite (and Russians far underrepresented as a percentage of the population). Moreover, the Jews formed a far more cohesive core than the rest of the elite because of their common social and cultural background (p. 236). The common understanding that the new elite had a very large Jewish representation resulted in pervasive anti-Jewish attitudes. In 1926, an Agitprop report noted:

The sense that the Soviet regime patronizes the Jews, that it is ‘the Jewish government,’ that the Jews cause unemployment, housing shortages, college admissions problems, price rises, and commercial speculation—this sense is instilled in the workers by all the hostile elements… If it does not encounter resistance, the wave of anti-Semitism threatens to become, in the very near future, a serious political question (p. 244).

Such widespread public perceptions about the role of Jews in the new government led to aggressive surveillance and repression of anti-Jewish attitudes and behavior, including the execution of Russian nationalists who expressed anti-Jewish attitudes. These public perceptions also motivated Jews to adopt a lower profile in the regime, as with Trotsky, who refused the post of commissar of internal affairs because it might lend further ammunition to the anti-Jewish arguments. From 1927 to 1932 Stalin established an ambitious public campaign to combat anti-Semitism that included fifty-six books published by the government and an onslaught of speeches, mass rallies, newspaper articles, and show trials “aimed at eradicating the evil” (p. 249).

THE DECLINE OF THE JEWS IN THE SOVIET UNION

Jews were able to maintain themselves as an elite until the end of the Soviet regime in 1991. On the whole, Jews were underrepresented as victims of the Great Terror. Jews also retained their elite status despite Stalin’s campaign in the late 1940s against Jewish ethnic and cultural institutions and their spokesmen.

Slezkine shows the very high percentages of Jews in various institutions in the late 1940s, including the universities, the media, the foreign service, and the secret police. The campaign against the Jews began only after the apogee of mass murder and deportations in the USSR.

Unlike the purges of the 1930s that sometimes targeted Jews as member of the elite (albeit at far less than their percentage of the elite), the anti-Jewish actions of the late 1940s and early 1950s were targeted at Jews because of their ethnicity. Similar purges were performed throughout Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe (pp. 313–314). “All three regimes [Poland, Romania, Hungary] resembled the Soviet Union of the 1920s insofar as they combined the ruling core of the old Communist underground, which was heavily Jewish, with a large pool of upwardly mobile Jewish professionals, who were, on average, the most trustworthy among the educated and the most educated among the trustworthy” (p. 314). Speaking of the situation in Poland, Khrushchev supported the anti-Jewish purge with his remark that “you have already too many Abramoviches.”

Whereas in the 1920s and 1930s children of the pillars of the old order were discriminated against, now Jews were not only being purged because of their vast overrepresentation among the elite, but were being discriminated against in university admissions. Jews, the formerly loyal members of the elite and willing executioners of the bloodiest regime in history, now “found themselves among the aliens” (p. 310).

And so began the exodus of Jews. Stalin died and the anti-Jewish campaign fizzled, but the Jewish trajectory was definitely downhill. Jews retained their elite status and occupational profile until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, but “the special relationship between the Jews and the Soviet state had come to an end—or rather, the unique symbiosis in pursuit of world revolution had given way to a unique antagonism over two competing and incommensurate nationalisms” (p. 330). A response of the Russians was “massive affirmative action” (p. 333) aimed at giving greater representation to underrepresented ethnic groups. Jews were targets of suspicion because of their ethnic status, barred from some elite institutions, and limited in their opportunities for advancement.

The Russians were taking back their country, and it wasn’t long before Jews became leaders of the dissident movement and began to seek to emigrate in droves to the United States, Western Europe, and Israel.

Applications to leave the USSR increased dramatically after Israel’s Six-Day War of 1967, which, as in the United States and Eastern Europe, resulted in an upsurge of Jewish identification and ethnic pride. The floodgates were eventually opened by Gorbachev in the late 1980s, and by 1994, 1.2 million Soviet Jews had emigrated — 43% of the total. By 2002, there were only 230,000 Jews left in the Russian Federation, 0.16% of the population. These remaining Jews nevertheless exhibit the typical Ashkenazi pattern of high achievement and overrepresentation among the elite, including six of the seven oligarchs who emerged in control of the Soviet economy and media in the period of de-nationalization (p. 362).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this dénouement did not result in any sense of collective guilt among Soviet Jews (p. 345) or among their American apologists. Indeed, American Jewish media figures who were blacklisted because of Communist affiliations in the 1940s are now heroes, honored by the film industry, praised in newspapers, their work exhibited in museums.

At the same time, the cause of Soviet Jews and their ability to emigrate became a critical rallying point for American Jewish activist organizations and a defining feature of neoconservatism as a Jewish intellectual and political movement. (For example, Richard Perle, a key neoconservative, was Senator Henry Jackson’s most important security advisor from 1969 to 1979 and organized Congressional support for the Jackson-Vanik Amendment linking US-Soviet trade to the ability of Jews to emigrate from the Soviet Union. The bill was passed over strenuous opposition from the Nixon administration.) Jewish activist organizations and many Jewish historians portray the Soviet Jewish experience as a sojourn in the land of the “Red Pharaohs” (p. 360). The historical legacy is that Jews were the passive, uncomprehending victims of the White armies, the Nazis, the Ukrainian nationalists, and the postwar Soviet state, nothing more.

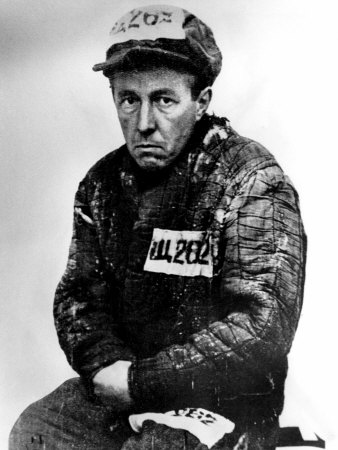

THE ISSUE OF JEWISH CULPABILITY

Alexander Solzhenitsyn calls on Jews to accept moral responsibility for the Jews who “took part in the iron Bolshevik leadership and, even more so, in the ideological guidance of a huge country down a false path… [and for the Jewish role in the] Cheka executions, the drowning of the barges with the condemned in the White and Caspian Seas, collectivization, the Ukrainian famine—in all the vile acts of the Soviet regime” (quoted on p. 360). But according to Slezkine, there can be no collective guilt.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn calls on Jews to accept moral responsibility for the Jews who “took part in the iron Bolshevik leadership and, even more so, in the ideological guidance of a huge country down a false path… [and for the Jewish role in the] Cheka executions, the drowning of the barges with the condemned in the White and Caspian Seas, collectivization, the Ukrainian famine—in all the vile acts of the Soviet regime” (quoted on p. 360). But according to Slezkine, there can be no collective guilt.

There can be little doubt that Lenin’s contempt for “the thick-skulled, boorish, inert, and bearishly savage Russian or Ukrainian peasant” was shared by the vast majority of shtetl Jews prior to the Revolution and after it. Those Jews who defiled the holy places of traditional Russian culture and published anti-Christian periodicals doubtless reveled in their tasks for entirely Jewish reasons, and, as Gorky worried, their activities not unreasonably stoked the anti-Semitism of the period.

Given the anti-Christian attitudes of traditional shtetl Jews, it is very difficult to believe that the Jews engaged in campaigns against Christianity did not have a sense of revenge against the old culture that they held in such contempt. Indeed, Slezkine reviews some of the works of early Soviet Jewish writers that illustrate the revenge theme. The amorous advances of the Jewish protagonist of Eduard Bagritsky’s poem “February” are rebuffed by a Russian girl, but their positions are changed after the Revolution when he becomes a deputy commissar. Seeing the girl in a brothel, he has sex with her without taking off his boots, his gun, or his trench coat—an act of aggression and revenge:

I am taking you because so timid

Have I always been, and to take vengeance

For the shame of my exiled forefathers

And the twitter of an unknown fledgling!

I am taking you to wreak my vengeance

On the world I could not get away from!

Slezkine seems comfortable with revenge as a Jewish motive. [His] argument that Jews were critically involved in destroying traditional Russian institutions, liquidating Russian nationalists, murdering the tsar and his family, dispossessing and murdering the kulaks, and destroying the Orthodox Church has been made by many other writers over the years, including Igor Shafarevich, a mathematician and member of the prestigious U. S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS). Shafarevich’s review of Jewish literary works during the Soviet and post-Soviet period agrees with Slezkine in showing Jewish hatred mixed with a powerful desire for revenge toward pre-revolutionary Russia and its culture.

But Shafarevich also suggests that the Jewish “Russophobia” that prompted the mass murder is not a unique phenomenon, but results from traditional Jewish hostility toward the non-Jewish world, considered tref (unclean), and toward non-Jews themselves, considered subhuman and as worthy of destruction. Both Shafarevich and Slezkine review the traditional animosity of Jews toward Russia, but Slezkine attempts to get his readers to believe that shtetl Jews were magically transformed in the instant of Revolution; although they did carry out the destruction of traditional Russia and approximately twenty million of its people, they did so only out of the highest humanitarian motives and the dream of utopian socialism, only to return to an overt Jewish identity because of the pressures of World War II, the rise of Israel as a source of Jewish identity and pride, and anti-Jewish policies and attitudes in the USSR.

This is simply not plausible.

* * *

The situation prompts reflection on what might have happened in the United States had American Communists and their sympathizers assumed power. The “red diaper babies” came from Jewish families which “around the breakfast table, day after day, in Scarsdale, Newton, Great Neck, and Beverly Hills have discussed what an awful, corrupt, immoral, undemocratic, racist society the United States is.” Indeed, hatred toward the peoples and cultures of non-Jews and the image of enslaved ancestors as victims of anti-Semitism have been the Jewish norm throughout history—much commented on, from Tacitus to the present.

It is easy to imagine which sectors of American society would have been deemed overly backward and religious and therefore worthy of mass murder by the American counterparts of the Jewish elite in the Soviet Union—the ones who journeyed to Ellis Island instead of Moscow. The descendants of these overly backward and religious people now loom large among the “red state” voters who have been so important in recent national elections. Jewish animosity toward the Christian culture that is so deeply ingrained in much of America is legendary. As Joel Kotkin points out, “for generations, [American] Jews have viewed religious conservatives with a combination of fear and disdain.” And as Elliott Abrams notes, the American Jewish community “clings to what is at bottom a dark vision of America, as a land permeated with anti-Semitism and always on the verge of anti-Semitic outbursts.”

These attitudes are well captured in Steven Steinlight’s charge that the Americans who approved the immigration restriction legislation of the 1920s—the vast majority of the population—were a “thoughtless mob” and that the legislation itself was “evil, xenophobic, anti-Semitic,” “vilely discriminatory,” a “vast moral failure,” a “monstrous policy.” In the end, the dark view of traditional Slavs and their culture that facilitated the participation of so many Eastern European shtetl Jews in becoming willing executioners in the name of international socialism is not very different from the views of contemporary American Jews about a majority of their fellow countrymen.

There is a certain enormity in all this. The twentieth century was indeed the Jewish century because Jews and Jewish organizations were intimately and decisively involved in its most important events. Slezkine’s greatest accomplishment is to set the historical record straight on the importance of Jews in the Bolshevik Revolution and its aftermath, but he doesn’t focus on the huge repercussions of the Revolution, repercussions that continue to shape the world of the twenty-first century. In fact, for long after the Revolution, conservatives throughout Europe and the United States believed that Jews were responsible for Communism and for the Bolshevik Revolution. The Jewish role in leftist political movements was a common source of anti-Jewish attitudes among a great many intellectuals and political figures.

In Germany, the identification of Jews and Bolshevism was widespread in the middle classes and was a critical part of the National Socialist view of the world. As historian Ernst Nolte has noted, for middle-class Germans, “the experience of the Bolshevik revolution in Germany was so immediate, so close to home, and so disquieting, and statistics seemed to prove the overwhelming participation of Jewish ringleaders so irrefutably,” that even many liberals believed in Jewish responsibility.

Jewish involvement in the horrors of Communism was also an important sentiment in Hitler’s desire to destroy the USSR and in the anti-Jewish actions of the German National Socialist government. Jews and Jewish organizations were also important forces in inducing the Western democracies to side with Stalin rather than Hitler in World War II.

Jewish involvement in the horrors of Communism was also an important sentiment in Hitler’s desire to destroy the USSR and in the anti-Jewish actions of the German National Socialist government. Jews and Jewish organizations were also important forces in inducing the Western democracies to side with Stalin rather than Hitler in World War II.

The victory over National Socialism set the stage for the tremendous increase in Jewish power in the post-World War II Western world, in the end more than compensating for the decline of Jews in the Soviet Union. As Slezkine shows, the children of Jewish immigrants assumed an elite position in the United States, just as they had in the Soviet Union and throughout Eastern Europe and Germany prior to World War II. This new-found power facilitated the establishment of Israel, the transformation of the United States and other Western nations in the direction of multiracial, multicultural societies via large-scale non-white immigration, and the consequent decline in European demographic and cultural preeminence. The critical Jewish role in Communism has been sanitized, while Jewish victimization by the Nazis has achieved the status of a moral touchstone and is a prime weapon in the push for massive non-European immigration, multiculturalism, and advancing other Jewish causes.

The Jewish involvement in Bolshevism has therefore had an enormous effect on recent European and American history. It is certainly true that Jews would have attained elite status in the United States with or without their prominence in the Soviet Union. However, without the Soviet Union as a shining beacon of a land freed of official anti-Semitism where Jews had attained elite status in a stunningly short period, the history of the United States would have been very different. The persistence of Jewish radicalism influenced the general political sensibility of the Jewish community and had a destabilizing effect on American society, ranging from the paranoia of the McCarthy era, to the triumph of the 1960s countercultural revolution, to the conflicts over immigration and multiculturalism that are so much a part of the contemporary political landscape.

It is Slezkine’s chief contention that the history of the twentieth century was a history of the rise of the Jews in the West, in the Middle East, and in Russia, and ultimately their decline in Russia. I think he is absolutely right about this. If there is any lesson to be learned, it is that Jews not only became an elite in all these areas, they became a hostile elite—hostile to traditional peoples and cultures of all three areas they came to dominate. Until now, the greatest human tragedies have occurred in the Soviet Union, but Israel’s record as an oppressive and expansive occupying power in the Middle East has made it a pariah among the vast majority of the governments of the world. And Jewish hostility toward the European-derived people and culture of the United States has been a consistent feature of Jewish political behavior and attitudes throughout the twentieth century. In the present, this normative Jewish hostility toward the traditional population and culture of the United States remains a potent motivator of Jewish involvement in the transformation of the U.S. into a non-European society.

Given this record of Jews as a hostile but very successful elite, I doubt that the continued demographic and cultural dominance of Western European peoples will be retained either in Europe or the United States and other Western societies without a decline in Jewish influence. The lesson of the Soviet Union (and Spain from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries) is that Jewish influence does wax and wane. Unlike the attitudes of the utopian ideologies of the twentieth century, there is no end to history.

___________

In another entry I will deal with the “second reason” why every decent person should become an anti-Semite: the Jewish role in shaping American immigration policies.