I have reread chapter 13 of William Pierce’s Who We Are on the whys of the decline and fall of Rome and it looks like a mirror-image of the present-day West and of America in particular.

Category: Ancient Rome

The following is my abridgement of chapter 13 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Nordic Virtues Led Romans to World Domination

Etruscan Kings Paved Way for Rome’s Fall

Levantines, Decadence, Capitalism Sank Rome

Today, when we speak of “Latins,” we reflexively think of short, swarthy, excitable people who are inordinately fond of loud rhythms, wine, spicy food, and seduction, and who aren’t to be taken very seriously. That is not an accurate image of all speakers of Romance languages, of course. Many individuals of French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian nationality are as racially sound as the average Swede or German. Yet, the image persists, and for good reason.

But the Latini, the Northern tribesmen who settled Latium in the ninth century B.C. and founded Rome a century later, were something altogether different. Most of today’s Latins share nothing with those of twenty-eight centuries ago except the name. Not only are the two strikingly different in appearance and temperament, but every element of the culture the original Latins created as an expression of their race-soul has been fundamentally transformed by those who claim that name today.

Above all, the Latini were a people to be taken seriously. They brought with them to Italy the spirit of the northern forests whence they had come. They took themselves and life very seriously indeed.

Duty, honor, responsibility: to the early Romans these were the elements which circumscribed a man’s life. Their virtues (the Latin root of the word means “manliness”) were strength of body and will, perseverance, sobriety, courage, hardiness, steadiness of purpose, attentiveness to detail, intelligence, and the characteristically Nordic will to order. Through these virtues they brought the world under their sway and created a civic edifice of such magnificence that it has ever since provided the standard against which all others are measured.

The Romans shaped the world around them—its institution, its politics, its attitudes, and its lifestyles—more extensively and more profoundly than anyone else has, and then they perished. That fact has fascinated and occupied the energies of historical scholars as no other topic. What were the reasons that the Romans rose so high and then fell so far?

Aristocrats only

The populus Romanus, it should be noted, did not include every inhabitant of Rome. Initially, in fact, it included only those persons who were blood members of a gens: i.e., the nobles, or patricians. After the individual households (familiae), the gentes were the fundamental social units among the early Romans, just as among the other Indo-European peoples. Their origin predates the Latin invasion of Italy; those persons born into them were, thus, all descendants of the warrior clans which originally seized the land and subjugated the aborigines.

The members of this warrior nobility, the patricians, were originally the whole people; to them belonged everything: land, livestock, religion, and law. They alone possessed a clan name (nomen gentilicium) and the right to display a coat of arms (jus imaginum).

Those who were not patricians, and, hence, not members of the populus Romanus, were the plebeians (plebs). Although not originally permitted to participate in the political or religious institutions of the populus, the plebeians were technically free. Many of them were the pre-Latin inhabitants of the seven hills beside the Tiber on which Rome was built; some undoubtedly came into the area later, as Rome’s influence grew. No direct evidence remains on the matter, but it nevertheless seems certain that there was a racial as well as a social difference between patricians and plebeians, with the latter having much less Nordic blood than the former.

Several social and political developments worked to diminish the racial distinction between patrician and plebeian with the passage of time. One of these developments was the patron-client relationship; another was the incorporation of an Etruscan element into the Roman population, including the acceptance of a number of gentes of Etruscan nobles into the Roman patrician class; a third was the extension of citizenship to the plebs.

As the social bond between patricians and plebeians grew, the social distance lessened. Many plebeians became, through hard work and good fortune, wealthy enough to rival the patrician class in their standard of living. And, although marriage between patrician and plebeian was strictly forbidden, there was nevertheless a flow of patrician genes into the plebeian class as a result of irregular liaisons between patrician men and plebeian women.

Latins, Sabines, Etruscans. Very early in its history, Romulus’ hilltop village of Latins joined forces with a neighboring village of Sabines, the Titienses. The Sabines and the Latins were of very closely related Indo-European stocks, and the amalgamation did little to change social institutions, other than doubling the number of senators.

A few years later, however, the Etruscan Luceres—of non-Indo-European stock—were absorbed by the growing Rome. Although the Etruscans remained a tribe apart from the Latin and Sabine inhabitants of the city, without patrician status, this condition was destined not to last.

It was Tarquin’s successor, Servius Tullius, who wrought changes which were to have much more profound racial consequences: in essence, Servius made the plebs a part of the populus Romanus. He accomplished this by overshadowing the patrician assembly, the Comitia Curiata, with two new popular assemblies, one civil and one military.

For administrative purposes, Servius divided the city and its territory into 30 “tribes.” These 30 administrative divisions, or wards, were tribal in name only, however; they were based solely on geography, and not on birth.

The patricians still ruled in the new Comitia Tributa, or tribal assembly, and provided the magistrates for the new wards, but Servius had laid the same groundwork for future political gains by the Roman plebs which Cleisthenes, just a few decades later, laid in Athens by reorganizing the tribal basis of the Athenian state along purely geographical lines.

Servius certainly cannot be accused of being a democrat. Yet he clearly initiated the process which eventually led to the ascendancy of gold over blood in Roman society, just as Solon had done in Athens a few years earlier.

The successor of Servius Tullius, Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin the Proud), partly repealed the changes the former had made. And Tarquin the Proud’s reign marked the end of Etruscan domination of Rome, as well as the end of the monarchy. The Tarquins were driven out of Rome by the Latins and Sabines in 509 B.C. (according to tradition), and the Roman Republic was born.

But the Etruscan kings (among whom Servius is included, although his origins and ethnicity are uncertain) had brought about two lasting changes which were racially significant: the Roman aristocracy of Indo-European Latins and Sabines had received a substantial non-Indo-European admixture by the admission of the nobility of the Luceres to patrician status, and the principle that citizenship (and its attendant rights and powers) should belong solely to the members of a racial elite had been compromised.

The following centuries saw the political power of the plebs increase greatly relative to that of the patricians, while wealth continued to gain weight relative to race and family.

The Romans survived the founding of the Republic by roughly a millennium, but we are not concerned in this series with the political and cultural details of their history, except as these details have a salient racial significance. Therefore, the emphasis in the following historical summary is rather different than that found in most textbooks on Roman history.

Let us focus on four factors: first, the growing racial diversity of the Roman state; second, the eventual decadence of Rome’s patricians; third, the differential in birthrates between Rome’s patrician and plebeian classes; and fourth, the effects on the Roman peasantry of large-scale slavery as a capitalist institution.

Non-white immigration

The Romans were an energetic and martial people, and the power, influence, and wealth which they wielded grew enormously during the period from the end of the sixth to the last quarter of the first century B.C., the life-span of the Republic. First all of Italy, then the rest of the Mediterranean world and the Middle East, and finally much of Nordic Europe came into their possession.

This vast area under Roman rule was inhabited by a great diversity of races and peoples. As time passed, the rights of citizenship were extended to more and more of them. Citizens or not, there was a huge influx of foreign peoples into Rome and the other parts of Italy. Some came as slaves, the spoils of Rome’s victorious wars, and many came voluntarily, attracted by Rome’s growing wealth.

After the Republic became the Empire, in the last quarter of the first century B.C., the flow of foreigners into Italy increased still further. The descendants of the Latin founders of Rome became a minority in their own country. Above all other factors, this influx of alien immigrants led to Rome’s demise and the extinction of the race which built her into the ruler of the world.

The importance of the immigration factor is, of course, barely mentioned, if at all, in the school history texts being published today, because those who control the content of the textbooks have planned the same fate for White America as that which overtook White Rome.

Nevertheless, the writers of Classical antiquity themselves clearly recognized and wrote about the problem, as do those few of today’s professional historians with courage enough to buck the blackout on the mention of race in history. An example of the latter is the distinguished Swedish historian Martin Nilsson, for many years professor at the University of Lund. In his Imperial Rome, Nilsson wrote:

Of greater variety than elsewhere was the medley of races in the capital, where individuals congregated from all quarters, either on business with the rulers and the government or as fortune seekers in the great city, where great possibilities were open to all. It is almost impossible for us to realize the extraordinarily motley character of the Roman mob. The only city in our own day which can rival it is Constantinople, the most cosmopolitan town in the world. Numerous passages in the works of Classical authors refer to it, from Cicero, who calls Rome a city formed by the confluence of nations, to Constantius, who, when he visited Rome, marveled at the haste with which all the human beings of the world flocked there….

There were Romans who viewed the population of the capital with deep pessimism. In Nero’s time (37-68 A.D.) Lucan said that Rome was not peopled by its own citizens but filled with the scourings of the world. The Oriental [by Oriental, Nilsson means Levantine, not Mongoloid] element seems to have been especially strong.

Jews, in particular, in order to get their hands on the wealth there, flocked to Rome in such enormous numbers that Emperor Tiberius, under pressure from the common people on whom the Jews were preying, was obliged to order them all deported in 19 A.D. The Jews sneaked back in even greater numbers, and Tiberius’ brother, Emperor Claudius, was forced to renew the deportation order against them a few years later, but without success. They had become so numerous and so well entrenched that the emperor did not have the energy to dislodge them.

Another distinguished historian, the late Tenney Frank, professor at Bryn Mawr and Johns Hopkins, made a careful survey of Roman tomb inscriptions. He studied 13,900 inscriptions, separating them into categories based on the ethnicity or probable ethnicity indicated by the names and corollary evidence. Professor Frank estimated that by the end of the first century A.D. 90 per cent of the free plebeians in Rome were Levantines or part-Levantines. Fewer than ten per cent could claim unmixed Italian ancestry, and of these even fewer were of pure Indo-European stock.

One problem which Frank ran into was the tendency of non-Italians to disguise their ancestry by changing their names. It was easy enough to separate Greek and Syrian and Hebrew names from Latin ones, but a Latin name which had been adopted rather than inherited could often only be detected by noting the non-Latin names of the parents on the same tomb.

Then too, just as Jewish name-changers today often give themselves away by choosing a non-Jewish first name which has become so popular among their brethren that few non-Jews would dream of burdening their own children with it (Murray, Seymour, Irving are examples), Frank found the same clues among many “Latin” names.

As for the Greek names, the great majority of them did not belong to Hellenes but to Levantines from the remnants of Alexander’s Oriental empire. The Roman poet Juvenal (62-142 A.D.) alluded to this when he wrote:

Sirs, I cannot bear

This Rome made Grecian; yet of all her dregs

How much is Greek? Long since Orontes’ [a river] stream

Hath fouled our Tiber with his Syrian waters,

Bearing upon his bosom foreign speech

And foreign manners…

C. Northcote Parkinson, the noted author and historian, sums up the effect of centuries of uncontrolled immigration in his East and West (1963): “Rome came to be peopled very largely by Levantines, Egyptians, Armenians, and Jews; by astrologers, tipsters, idlers, and crooks.” The name “Roman,” in other words, came to mean as little as the name “American” is coming to mean today. And yet, just as White Americans are bringing about their downfall through greed and timidity and indifference, so did Rome’s patricians cause their own end.

In Rome’s earliest days, when the populus Romanus was entirely of noble birth, duty, honor, and responsibility counted for everything, as mentioned above. A Roman valued nothing above his honor, put nothing before his obligations to the community. Even after Rome’s conquests brought wealth and luxury to her citizens, her patricians could still produce men like Regulus, stern, honorable, unyielding.

Bread and circuses

But wealth inexorably undermined the old virtues. Decadence rotted the souls of the noble Romans. While the mongrel mobs were entertained by the debased spectacles in the Colosseum (not unlike the distraction of today’s rabble by non-stop television), the patricians indulged themselves with every new vice and luxury that money and a resourceful merchant class could provide. Pampered, perfumed, manicured, and attended by numerous slaves, the effete aristocracy of the first century A.D. was a far cry from the hard and disciplined ruling class of a few centuries earlier.

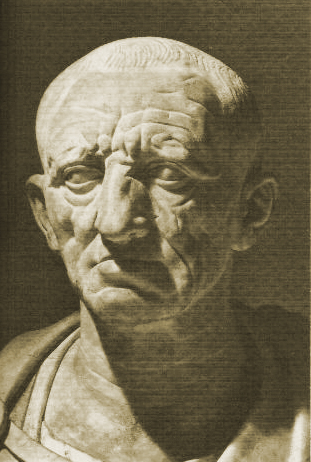

Just as there are Americans today who understand where the weakness and lack of discipline of their people are leading them and who speak out against these things, so were there Romans who tried to stem the tide of decadence engulfing the Republic. One of these was M. Porcius Cato (“the Censor”), whose public career spanned the first half of the second century B.C.

Just as there are Americans today who understand where the weakness and lack of discipline of their people are leading them and who speak out against these things, so were there Romans who tried to stem the tide of decadence engulfing the Republic. One of these was M. Porcius Cato (“the Censor”), whose public career spanned the first half of the second century B.C.

Cato was born and raised on his father’s farm and then spent 26 years fighting in Rome’s legions before entering politics. Early in his career, having been appointed governor (praetor) of Sardinia, Cato set the pattern he would follow the rest of his life: he expelled all the moneylenders from the island, earning the undying hatred of the Jews and a reputation as a fierce anti-Semite.

Later Cato was elected censor in Rome. The duties of a censor were to safeguard public morality and virtue and to conduct a periodic census of people and property for military and tax purposes. Cato took these duties very seriously. He assessed jewelry and other luxury items at ten times their actual value, and he dealt promptly and severely with disorder and degeneracy.

In the Senate Cato spoke out repeatedly against the foreign influences in philosophy, religion, and lifestyle which were encroaching on the traditional Roman attitudes and manners. As a result, Rome’s “smart set” condemned him (privately, for he was too powerful to attack openly) as an archreactionary and an enemy of “progress.”

In the field of foreign policy, Cato was adamantly opposed to the integration of the Semitic East into the Roman world. He wanted Rome to concentrate on the western Mediterranean and to deal with the Levant only at sword point. Unfortunately, there were few men of Cato’s fiber left among the Romans by the second century.

Declining Birthrate. One of the most fateful effects of decadence was the drastic decline in the birthrate of the Roman nobility. Decadence is always accompanied by an increase in egoism, a shifting of focus from race and nation to the individual. Instead of looking on bearing and raising children as a duty to the state and a necessity for the perpetuation of their gens and tribe, upper-class Romans came to regard children as a hindrance, a limitation on their freedom and pleasure. The “liberation” of women also contributed heavily to this change in outlook.

The failure of the patrician class to reproduce itself alarmed those Roman leaders with a sense of responsibility to the future. Emperor Augustus tried strenuously to reverse the trend by issuing several decrees regarding family life. Heavy penalties were set for celibacy or for marriage with the descendants of slaves. Eventually, Augustus ordered that every noble Roman between the ages of twenty-five and sixty must be married or, at least, betrothed.

Suicide of the Nobility. In 9 A.D. tax advantages and other preferences were granted to the parents of three or more children; unmarried persons were barred from the public games and could not receive inheritances, while the childless married person could receive only half of any inheritance left to him.

All these measures failed. Augustus’ own daughter, Julia, was a thoroughly liberated member of the “jet set” of her time, who considered herself far too sophisticated to be burdened with motherhood; in embarrassment, Augustus banished her to an island.

From the dictatorship of Julius Caesar to the reign of Emperor Hadrian, a century and a half, one can trace the destinies of forty-five leading patrician families: all but one died out during that period. Of 400 senatorial families on the public records in 65 A.D., during the reign of Nero, all trace of half of them had vanished by the reign of Nerva, a single generation later.

Rise of Capitalism. As the patricians declined in numbers, the Roman peasantry also suffered, but for a different reason. The later years of the Republic saw the rise of agricultural capitalism, with wealthy entrepreneurs buying up vast estates, working them with slaves and driving the freeborn small farmers out of the marketplace.

By the tens of thousands the Latin and Sabine yeomen were bankrupted and forced to abandon their farms. They fled to the city, where most of them were swallowed up in the urban mob.

The capitalist nouveaux riches who came to wield much of the power and influence in Rome lost by the dwindling patricians were an altogether new type of Roman. Petronius’ fictional character Trimalchio is their archetype. Tenney Frank wrote of these “new Romans”:

It is apparent that at least the political and moral qualities which counted most in the building of the Italian federation, the army organization, the provincial administrative system of the Republic, were the qualities most needed in holding the Empire together. And however brilliant the endowment of the new citizens, these qualities they lacked. The Trimalchios of the Empire were often shrewd and daring businessmen, but their first and obvious task, apparently was to climb by the ladder of quick profits to a social position in which their children, with Romanized names, could comfortably proceed to forget their forebears. The possession of wealth did not, as in the Republic, suggest certain duties toward the commonwealth.

Many historians have remarked on the fact that the entire spirit of the Roman Empire was radically different from that of the Roman Republic. The energy, foresight, common sense, and discipline which characterized the Republic were absent from the Empire. But that was because the race which built the Republic was largely absent from the Empire; it had been replaced by the dregs of the Orient.

The change in attitudes, values, and behavior was due to a change in blood. The changing racial composition of Rome during the Republic paved the way for the unchecked influx of Levantine blood, manners, and religion during the Empire.

But it also set the stage for a new ascendancy of the same Northern blood which had first given birth to the Roman people. We will look at the conquest of Rome by the Germans. First, however, we must backtrack and see what had been happening in the North during the rise and fall of Rome.

The following is my abridgement of chapter 14 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

One of the Principal Indo-European Peoples Who Founded Europe

Celts Were Fierce Warriors, Master Craftsmen

Roman Conquest Drowned Celtic Europe in Blood

In the last few installments we have dealt with those Indo-European peoples which, after leaving their homeland north of the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, between the Urals and the Dnieper, invaded regions of the world heavily populated by alien races. Some—the Aryans, Kassites, Mitanni, Hittites, Phrygians, and Philistines—went into the Middle East, conquered the natives, and then gradually sank down into them through racial mixing over the course of millennia.

Others—the Achaeans, Dorians and Latins—went southwest, into the Greek and Italian peninsulas, conquered the aboriginal Mediterraneans already there, and founded the great civilizations of Classical antiquity. Although the racial differences between them and the natives were not as great as for those who went into the Middle East, mixing took its toll of these Indo-Europeans as well, and they gradually lost their original racial character.

Four Indo-European Peoples. The Indo-Europeans who invaded [the north] of Europe were able to remain racially pure, to a much greater extent than their cousins who invaded the more southerly and easterly regions, even to the present day. They established, in effect, a new Indo-European heartland in northern Europe. We shall look at four great divisions of these Indo-European peoples: the Celts, Germans, Balts, and Slavs.

These divisions are distinguished one from another by language, geography, and time of appearance on the stage of world history, as well as by their subsequent fates. But one salient fact should be kept in mind throughout the individual treatments of the Celts, Germans, Balts, and Slavs which follow: they are all branches from the same trunk.

Originally, Celt, German, Balt, and Slav were indistinguishably Nordic. The Celts were the first group to make an impact on the Classical world, and so we will deal with them first. (The “C” may be pronounced either with an “s” sound, the result of French influence, or with a “k” sound. The latter was the original pronunciation.) The reason the Celts interacted with the Greeks and Romans before the other groups did is that their wanderings took them farthest south. The Roman conquest of southeastern Europe, Gaul, and Britain destroyed the greater part of Celtic culture, as well as doing an enormous amount of racial damage.

But the Celts themselves, as much as anyone else, were responsible for the decline of their racial fortunes. They settled in regions of Europe which, although not so heavily Mediterraneanized as Greece and Italy, were much more so than the German, Baltic, and Slavic areas. And, as has so often been the case with the Indo-Europeans, for the most part they did not force the indigenous populations out of the areas they conquered, but made subjects of them instead.

Thus, many people who think of themselves as “Celts” today are actually more Mediterranean than Celtic. And others, with Latin, Germanic, or Slavic names, are actually of nearly unmixed Celtic descent.

In this installment we will look at the origins of the Celts and at their interaction with the Romans.

The early Celts were not literate, and we are, therefore, dependent on Classical authors for much of what we know about Celtic mores, lifestyles, and behavior, as well as the physical appearance of the Celts themselves. The fourth-century Byzantine writer, Ammianus Marcellinus, drawing on reports from the first century B.C., tells us that the Celts (or Gauls, as the Romans called them) were fastidious, fair, and fierce:

The Gauls are all exceedingly careful of cleanliness and neatness, nor in all the country could any man or woman, however poor, be seen either dirty or ragged.

Nearly all are of a lofty stature, fair and of ruddy complexion: terrible from the sternness of their eyes, very quarrelsome, and of great pride and insolence. A whole troop of foreigners would not be able to withstand a single Gaul if he called his wife to his assistance, who is usually very strong and with blue eyes.

All the Classical writers agree in their descriptions of the Celts as being tall, light-eyed, and with blond or red hair, which they wore long. Flowing, abundant mustaches seem to have been a Celtic national trait.

And the favorite national pastime seems to have been fighting. Born to the saddle and bred to arms, the Celts were a warlike race, always ready for a brawl. Excellent horsemen and swordsmen, they were heartily feared by all their enemies.

Perhaps we should not be surprised that these equestrian warriors invented chain-link armor and iron horseshoes and were the first to learn how to make seamless iron tires for wagons and war chariots. But the Celts were also the inventors of soap, which they introduced to the relatively unwashed Greeks and Romans. Their inventive genius also manifested itself in the numerous iron woodworking tools and agricultural implements which they developed. They did not build castles, as such, but depended instead on strategically located hilltops, fortified with earthworks and palisades, as places of retreat in wartime.

Gradually these hill forts, or oppida (as the Romans called them), gained permanent inhabitants and enough amenities so that they could be considered towns. They became the sites of regular fairs and festivals, and centers of trade as well as defense.

Celtic society, following the customary Indo-European pattern, was hierarchical. At the top was a fighting and hunting aristocracy, always purely Celtic. At the bottom were the small farmers, the servants, and the petty craftsmen. The racial composition of this class varied from purely Celtic to mostly Mediterranean, depending on the region.

Relations between the sexes were open and natural, and—in contrast to the norm for Mediterranean societies—Celtic women were allowed a great deal of freedom.

When the wife of Sulpicius Severus, a Romanized fourth-century historian, reproached the wife of a Celtic chieftain for the wanton ways of Celtic women, the Celtic woman replied: “We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women: for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest.” In fourth-century Rome, of course, virtually all the wealth was in the hands of “the vilest” men: Jews, Syrians, and other Oriental immigrants who dominated commerce and constituted the nouveaux riches.

The ancestors of the Celts brought the solar religion of their Indo-European homeland with them to the areas they invaded; three-armed and four-armed swastikas, as solar symbols, are an omnipresent element in Celtic art, as is the four-spoked sun wheel. One of the most widely revered Celtic gods, Lug (or Lugh), had many of the attributes of the Germanic Wotan, and one of his designations, Longhanded Lug, referred to his role as a solar deity, whose life-giving force reached everywhere.

By the time of the Roman conquest, however, many extraneous elements had become inseparably blended into Celtic religion. The druids practiced not only solar rites, but some rather dark and nasty ones of Mediterranean origin as well.

Many later writers have not been as careful as Caesar was and tend to lump all Celtic-speaking populations together as “Gauls,” while sharply distinguishing them from the Germans. As a matter of fact, there was a much greater affinity between the Celts and the Germans, despite the language difference, than there was between the truly Celtic elements among the Gauls and the racially different but Celtic-speaking Mediterranean and Celtiberian elements.

In the British Isles the racial effects of the fifth-century B.C. Celtic invasions varied. In some areas indigenous Nordic populations were reinforced, and in others indigenous Mediterranean or mixed populations diluted the fresh Nordic wave.

Brennus Sacks Rome. Around 400 B.C. Celts invaded northern Italy in strength, establishing a permanent presence in the Po valley, between the Alps and the Apennines. They pushed out the resident Etruscans and Ligurians, founded the city of Milan, and began exploring possibilities for further expansion south of the Apennines.

In 390 B.C. a Celtic army under their chieftain Brennus defeated the Roman army and occupied Rome. The Celts were not prepared to stay, however, and upon payment of an enormous ransom in gold by the Romans they withdrew again to northern Italy.

In the following centuries there were repeated clashes between adventurous Celts and the people of the Classical civilizations to the south. In the third century B.C. a Celtic army ravaged Macedonia and struck deep into Greece, while another group of Celts, the Galatae, invaded central Asia Minor. Three centuries later the latter were still in place; they were the Galatians of the New Testament.

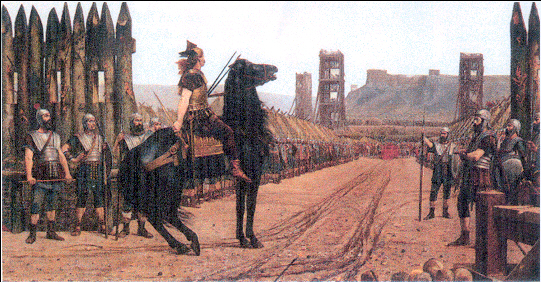

[Roman revenge.] Celtic bands continued to whip Roman armies, even to the end of the second century B.C., but then Roman military organization and discipline turned the tide. The first century B.C. was a time of unmitigated disaster for the Celts. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul was savage and bloody, with whole tribes, including women and children, being slaughtered by the Romans.

By the autumn of 54 B.C, Caesar had subdued Gaul, having destroyed 800 towns and villages and killed or enslaved more than three million Celts. And behind his armies came a horde of Roman-Jewish merchants and speculators, to batten on what was left of Gallic trade, industry, and agriculture like a swarm of locusts. Hundreds of thousands of blond, blue-eyed Celtic girls were marched south in chains, to be pawed over by greasy, Semitic flesh-merchants in Rome’s slave markets before being shipped out to fill the bordellos of the Levant.

Vercingetorix. Then began one, last, heroic effort by the Celts of Gaul to throw off the yoke of Rome, thereby regaining their honor and their freedom, and—whether consciously or not—reestablishing the superiority of Nordic mankind over the mongrel races of the south. The ancestors of the Romans had themselves established this superiority in centuries past, but by Caesar’s time Rome had sunk irretrievably into the quagmire of miscegenation and had become the enemy of the race which founded it.

Vercingetorix. Then began one, last, heroic effort by the Celts of Gaul to throw off the yoke of Rome, thereby regaining their honor and their freedom, and—whether consciously or not—reestablishing the superiority of Nordic mankind over the mongrel races of the south. The ancestors of the Romans had themselves established this superiority in centuries past, but by Caesar’s time Rome had sunk irretrievably into the quagmire of miscegenation and had become the enemy of the race which founded it.

The rebellion began with an attack by Ambiorix, king of the Celtic tribe of the Eburones, on a Roman fortress on the middle Moselle. It spread rapidly throughout most of northern and central Gaul. The Celts used guerrilla tactics against the Romans, ruthlessly burning their own villages and fields to deny the enemy food and then ambushing his vulnerable supply columns.

For two bloody years the uprising went on. Caesar surpassed his former cruelty and savagery in trying to put it down. When Celtic prisoners were taken, the Romans tortured them hideously before killing them. When the rebel town of Avaricum fell to Caesar’s legions, he ordered the massacre of its 40,000 inhabitants.

Meanwhile, a new leader of the Gallic Celts had come to the fore. He was Vercingetorix, king of the Arverni, the tribe which gave its name to France’s Auvergne region. His own name meant, in the Celtic tongue, “warrior king,” and he was well named.

Vercingetorix came closer than anyone else had to uniting the Celts. He was a charismatic leader, and his successes against the Romans, particularly at Gergovia, the principal town of the Arverni, roused the hopes of other Celtic peoples. Tribe after tribe joined his rebel confederation, and for a while it seemed as if Caesar might be driven from Gaul.

But unity was still too new an experience for the Celts, nor could all their valor make up for their lack of the long experience of iron discipline which the Roman legionaries enjoyed. Too impetuous, too individualistic, too prone to rush headlong in pursuit of a temporary advantage instead of subjecting themselves always to the cooler-headed direction of their leaders, the Celts soon dissipated their chances of liberating Gaul.

Finally, in the summer of 52 B.C., Caesar’s legions penned up Vercingetorix and 80,000 of his followers in the walled town of, Alesia, on the upper Teaches of the Seine. Although an army of a quarter-million Celts, from 41 tribes, eventually came to relieve besieged Alesia, Caesar had had time to construct massive defenses for his army. While the encircled Alesians starved, the Celts outside the Roman lines wasted their strength in futile assaults on Caesar’s fortifications.

Savage End. In a valiant, self-sacrificing effort to save his people from being annihilated, Vercingetorix rode out of Alesia, on a late September day, and surrendered himself to Caesar. Caesar sent the Celtic king to Rome in chains, kept him in a dungeon for six years, and then, during the former’s triumphal procession of 46 B.C., had him publicly strangled and beheaded in the Forum, to the wild cheers of the city’s degraded, mongrel populace.

After the disaster at Alesia, the confederation Vercingetorix had put together crumbled, and Caesar had little trouble in extinguishing the last Celtic resistance in Gaul. He used his tried-and-true methods, which included chopping the hands off all the Celtic prisoners he took after one town, Uxellodunum, commanded by a loyal adjutant of Vercingetorix, surrendered to him.

Decadent Rome did not long enjoy dominion of the Celtic lands, however, because another Indo-European people, the Germans, soon replaced the Latins as the masters of Europe.

The following is my abridgement of chapter 15 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Ancient Germans, German Growth,

Roman Imperialism Led to Conflict

The first wave of Battle-Axe People to leave the ancient Nordic heartland in the forests and steppes of southern Russia appeared in the Germanic area of northern Europe even before the Neolithic Revolution had become well established there, prior to 4,000 B.C.

It would be incorrect, of course, to refer to these earliest Nordic immigrants as “Germans.” All that can be said of them, just as of those immigrants south of them who later gave birth to the Celts, is that they were Indo-Europeans. The process of cultural-ethnic differentiation had not resulted in the fairly clear-cut distinctions which allowed one group of people to be identified as Germans, another as Celts, and a third as Balts until approximately the first half of the first millennium B.C.

By about 2,000 B.C., however, the ancestors of the Germans—call them proto-Germans—were at home in southern Sweden, the Danish peninsula, and the adjacent lands between the Elbe and the Oder. To the east were the proto-Balts, to the west and south the proto-Celts.

From this tiny proto-German homeland, about the size of the state of Tennessee, the Germans expanded their dominion during the ensuing 3,000 years over all of Europe, from Iceland to the Urals, ruling over Celts, Balts, Slavs, Latins, and Greeks, as well as the non-Indo-European peoples of the Roman Empire. After that it was Germanic peoples, primarily, who discovered, settled, and conquered North America and who, until the internal decay of the last few decades, wielded effective political power even over the non-White hordes of Asia and Africa.

German expansion. Seventeen centuries before the Teutonic Order conquered the Baltic lands, German expansion eastward along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea had extended German settlement and rule from the Oder to the Vistula. At the same time, expansion was also taking place toward the west and the south, bringing about mingling—and often conflict—between Germans and Celts. With the Roman conquest of Gaul in the first century B.C., direct conflict between the expanding Germans and still mighty and expanding Rome became inevitable.

Actually the death struggle between Latins and Germans began even before Caesar’s subjection of Gaul. Late in the second century two neighboring German tribes, the Cimbrians and the Teutons, left their homes in the Danish peninsula because, they said, of the sinking of much of their low-lying land into the sea. Some 300,000 in number, they headed south, crossing the Tyrolese Alps into northern Italy in 113 B.C., where they asked the Romans for permission either to settle or to cross Roman territory into the Celtic lands to the west.

The Roman consul, Papirius Carbo, attempted to halt them, and they defeated his army. The Germans then proceeded westward into Gaul and went as far as Spain, where they raised havoc. Ten years later, however, they returned to northern Italy.

This time they were met by a more competent Roman general, the consul Gaius Marius. In two horrendous battles, in 102 and 101 B.C., Marius virtually exterminated the Teutons and the Cimbrians. So many Teutons were massacred at Aquae Sextiae in 102 that, according to a contemporary Roman historian, their blood so fertilized the earth that the orchards there were especially fruitful for years afterward, and German bones were used to build fences around the vineyards.

At Vercelli the Cimbrians met a similar fate the following year; more than 100,000 were slaughtered. When the German women saw their men being defeated, they first slew their children and then killed themselves in order to avoid the shame of slavery.

The annihilation of these two German nations was followed by a few decades in which Italy remained relatively safe from further incursions from the north. The Germans’ territory was bounded, roughly, on the east by the Vistula and on the south by the Danube. In the west the boundary was less definite, and the Germans west of the Rhine came into repeated conflict with Roman armies in Gaul.

Tacitus on the Germans. The Romans were naturally curious about the teeming tribes of fierce, warlike people beyond the Rhine who dared contest their conquest of the lands in northern Gaul, and several Roman writers enumerated them and described their way of life, most notably the historian Gaius Cornelius Tacitus. Writing in a first-century Rome which was thoroughly mongrelized, Tacitus was strongly impressed by the Germans’ apparent racial homogeneity:

I concur in opinion with those who deem the Germans never to have intermarried with other nations but to be a pure and unmixed race, stamped with a distinct character. Hence, a family likeness pervades the whole, though their numbers are so great. Their eyes are stern and blue, their hair ruddy, and their bodies large, powerful in sudden exertion, but impatient of toil and not at all capable of sustaining thirst and heat. They are accustomed by their climate to endure cold and hunger.

When the Germans fight, wrote Tacitus, perhaps remembering the example of the Teutons and Cimbrians, “they have within hearing the yells of their women and the cries of their children.”

Tradition relates that armies beginning to give way have been rallied by the females, through the earnestness of their supplications, the interposition of their bodies, and the pictures they have drawn of impending slavery, a calamity which these people bear with more impatience for their women than themselves.

If these appeals were not sufficient to elicit honorable behavior from each and every German, Tacitus added, their fellow tribesmen dealt with them severely: “Traitors and deserters are hanged; cowards and those guilty of unnatural practices are suffocated in mud under a hurdle.” Subject to the same punishment as cowards and homosexuals were draft dodgers: those who failed to present themselves for military service when summoned.

The education of the German youth stressed not only bravery and skill in arms, but loyalty in the highest degree. Tacitus gives an interesting description of the mutual obligations between a German leader and his companions in arms:

The Germans transact no business, public or private, without being armed, but it is not customary for any person to assume arms until the state has approved his ability to use them. Then, in the midst of the assembly, either one of the chiefs, or the father, or a relative, equips the youth with a shield and a spear. These are to them the manly gown (toga virilis); this is the first honor conferred on youth. Before, they are considered as part of a household; afterwards, of the state.

There is a great emulation among the companions as to which shall possess the highest place in the favor of their chief, and among the chiefs as to which shall excel in the number and valor of this companions. It is their dignity and their strength always to be surrounded by a large body of select youth: an ornament in peace, a bulwark in war.

Thus, already in Tacitus’ time, was the foundation in existence upon which the medieval institutions of chivalry and feudalism would rest.

The philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, also writing in the first century, shared Tacitus’ respect for the Germans’ martial qualities: “Who are braver than the Germans? Who more impetuous in the charge? Who fonder of arms, in the use of which they are born and nourished, which are their only care?”

Caesar, Tacitus, and other writers also described other attributes of the Germans and various aspects of their lives: their shrines, like those of the Celts and the Balts, were in sacred groves, open to the sky; their family life (in Roman eyes) was remarkably virtuous, although the German predilection for strong drink and games of chance must have been sorely trying to wives; they were extraordinarily hospitable to strangers and fiercely resentful of any infringements on their own rights and freedoms; each man jealously guarded his honor, and a liar was held in worse repute than a murderer; usury and prostitution were unknown among them.

The following is my abridgement of chapter 16 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Death Struggle Between Germany and Rome

Decided Fate of White Race

Hermann Was Savior of Europe & White Race

Julius Caesar’s conquest of all the Celts and Germans west of the Rhine and his punitive raids into the German lands on the other side of the river bought time for the Romans to concentrate their military efforts against the still independent Celts inhabiting the Swiss and Austrian Alps and the lowlands between the Alps and the Danube, from Lake Constance to Vienna. More than three decades of intermittent warfare by Caesar and his successors finally subdued these Celts, and their lands became the Roman provinces of Rhaetia, Noricum, and Pannonia.

Germania Magna. By 15 B.C. the Danube had been established as the dividing line between the Roman Empire and the free German lands to the north—or Germania Magna, as the Romans named this territory bounded on the west, the south, and the east by the Rhine, the Danube, and the Vistula, respectively. The conquered German lands west of the Rhine, in Alsace, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the southern Netherlands, were divided into the Roman provinces of Upper and Lower Germany.

In 12 B.C. Emperor Augustus sent his stepson Drusus, who had played a major role in the subjection of the Celts, to the mouth of the Rhine to launch an invasion of Germania Magna. Although initially unsuccessful, Drusus led repeated campaigns against the Germans, and by 9 B.C. had defeated several tribes, most notably the Chatti, and pushed more than 200 miles into Germania Magna, reaching the Elbe.

Tribal Names. At this point an aside on the names of the German tribes may be helpful; otherwise we may easily become confused by the proliferation of often-conflicting designations given to the various tribes and groupings of tribes by the Romans, the Germans, and others. Because the ancient Germans were, for most practical purposes, illiterate (the Germans’ runes were used for inscriptions but not for writing books), the earliest German tribal names we have are those recorded by the Romans: Batavi, Belgae, Chatti, Chauci, Cherusci, Cimbri, Eburones, Frisii, Gothones, Hermunduri, Langobardi, Marcomanni, Saxones, Suevi, Teutones, etc. It is assumed that in most cases these were reasonable approximations to the actual German names.

In some cases these tribal names assigned by the Romans of Caesar’s time have survived in the names of modern nations or provinces: Belgium, Saxony, Lombardy, Gotland, and so on. More often they have not; the great stirring up of the nations of Europe between the latter part of the second century and the middle of the sixth century A.D.—the Voelkerwanderung, or wandering of the peoples—profoundly changed the German tribal groupings. Some tribes vanished without a trace; others reappeared as elements in new tribal configurations which combined many of the older tribes.

Thus, the Saxons of the eighth century consisted not only of the Saxones known to the Romans, but of many other tribal elements as well. The Franks likewise arose after Caesar’s time as a confederation of many German tribes.

The Romans referred to all the German tribes collectively as Germani, but this was apparently originally the name of only a single minor tribe, which later lost its independent existence. In similar manner the Romanized Franks of a later day referred to all their German neighbors by the name of a single tribal grouping which arose during the Voelkerwanderung, the Alamanni; the French name for any German is still allemand.

Conquests. Over the next dozen years the Roman military machine continued to consolidate and expand its conquests in Germania Magna. Most of the independent tribes left were those east of the Elbe. Some, like the Marcomanni, had been forced to leave their ancestral lands in the west and resettle east of the Elbe in order to avoid defeat by the Romans. The Germans were on the defensive everywhere, and they seemed well on the way to suffering the collective fate of the Celts.

They were finally beginning to learn one vital lesson, however: they must either unite in the face of the common enemy or become extinct; the independence of the various tribes was a luxury they could no longer afford. A king of the Marcomanni, Marbod, succeeded in uniting most of the tribes east of the Elbe and organizing a standing draft army of 70,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry from among them, the first time the Germans had accomplished such a feat.

The imperial representative in the conquered German lands was Publius Quintilius Varus, who was more a lawyer and a politician than a general. As an administrator he was brutal, arbitrary, and rapacious. Overturning all local customs, contemptuous of German tradition and sensibility, Varus applied the same measures against the tribes of Germania Magna which he had used earlier while he was proconsul in the Middle East and which Caesar had employed successfully to break the spirit of the Celts in Gaul. He succeeded instead in transforming the respect Germans had learned for Roman power into a bitter and implacable hatred.

The 19th-century English historian Edward Creasy describes especially well the German reaction to Varus and his army:

Accustomed to govern the depraved and debased natives of Syria, a country where courage in man and virtue in woman had for centuries been unknown, Varus thought that he might gratify his licentious and rapacious passions with equal impunity among the high-minded sons and pure-spirited daughters of Germany. When the general of any army sets the example of outrages of this description, he is soon faithfully imitated by his officers and surpassed by his still more brutal soldiery. The Romans now habitually indulged in those violations of the sanctity of the domestic shrine and those insults upon honor and modesty by which far less gallant spirits than those of our Teutonic ancestors have often been maddened into insurrection.

Hermann the Cheruscer. As the latter-day Romans were shortly to learn, the Germans dared a great deal. There came to the fore among the wretched, conquered tribes a German leader cast in the mold of the Celt Vercingetorix. Unlike the case with the latter, however, this new leader’s daring brought success. He was Hermann, son of Segimar, king of the Cherusci. The Romans called him Arminius. In Creasy’s words:

It was part of the subtle policy of Rome to confer rank and privileges on the youth of the leading families in the nations which she wished to enslave. Among other young German chieftains Arminius and his brother, who were the heads of the noblest house in the tribe of the Cherusci, had been selected as fit objects for the exercise of this insidious system. Roman refinements and dignities succeeded in denationalizing the brother, who assumed the Roman name of Flavius and adhered to Rome throughout all her wars against his country. Arminius remained unbought by honors or wealth, uncorrupted by refinement or luxury. He aspired to and obtained from Roman enmity a higher title than ever could have been given him by Roman favor.

Shortly before 1 A.D. Hermann went to Rome to learn the Roman ways and language. He was 17 or 18 years old. He served five years in a Roman legion and became a Roman citizen, a member of the equites, or knightly class. He was sent by Augustus to aid in the suppression of the rebellion in Pannonia and Dalmatia.

What Hermann learned about the Romans redoubled his hatred of them. Again, Creasy’s words on the subject can hardly be bettered:

Vast, however, and admirably organized as the fabric of Roman power appeared on the frontiers and in the provinces, there was rottenness at the core. In Rome’s unceasing hostilities with foreign foes and still more in her long series of desolating civil wars, the free middle classes of Italy had almost wholly disappeared. Above the position which they had occupied an oligarchy of wealth had reared itself; beneath that position a degraded mass of poverty and misery was fermenting. Slaves, the chance sweepings of every conquered country, shoals of Africans, Sardinians, Asiatics, Illyrians, and others, made up the bulk of the population of the Italian peninsula. The foulest profligacy of manners was general in all ranks….

With bitter indignation must the German chieftain have beheld all this and contrasted it with the rough worth of his own countrymen: their bravery, their fidelity to their word, their manly independence of spirit, their love of their national free institutions, and their loathing of every pollution and meanness. Above all he must have thought of the domestic virtues which hallowed a German home; of the respect there shown to the female character and of the pure affection by which that respect was repaid. His soul must have burned within him at the contemplation of such a race yielding to these debased Italians.

When he returned to his people at the age of 25, Hermann was given a Roman command under Varus. He immediately set to work organizing a revolution. The most difficult obstacle he had to overcome was neither the Germans’ lack of military stores or even a single walled fortress, nor their traditional disunity; it was the opposition from the conservative faction among his own people.

As is always so with conservatives, they preferred immediate prosperity under Roman rule, through the trade opportunities it offered or through advantages bestowed on individual leaders by the Romans, to freedom, honor, and the long-range preservation and promotion of their own stock. One of the most hostile of these Romanized conservatives was Hermann’s own father-in-law. Nevertheless, Hermann prevailed over the conservative opposition and won most of the leaders of the Cherusci and the neighboring tribes to his conspiracy.

In the summer of 9 A.D. Varus’ army, consisting of five legions, was encamped among the Saxons, west of the Weser in the modern state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Late in the month of September Hermann contrived to have a localized rebellion break out among some tribes to the east, and messengers soon arrived at Varus’ camp with news of the insurrection. Varus immediately set out with three of his legions to crush the revolt, giving Hermann the task of gathering up the Romans’ German auxiliary forces and following him.

Hermann sprang his carefully planned trap. Instead of gathering an auxiliary force to support Varus, he sent his agents speeding the revolutionary call to the tribes, far and near.

Hermann then set out in pursuit of Varus, catching up with him amid the wild ravines, steep ridges, and tangled undergrowth of the Teutoburger Forest, about 20 miles west of the Weser, near the present town of Detmold. The progress of the Roman army had been severely hampered by the heavy autumn rains and the marshy condition of the ground, and Hermann fell on Varus’ legions with a suddenness and fury which sent the Romans reeling.

For nearly three days the battle raged with a ferocity which exacted a heavy toll from both sides. The Germans employed guerrilla tactics, suddenly attacking the floundering Roman columns from an unexpected quarter and then withdrawing into the dense forest before the Romans could group themselves into effective fighting formation, only to attack again from a different quarter.

On the third day of battle the exhausted remnants of Varus’ army panicked and broke, and the Germans annihilated them. Once more, we will let Creasy tell the story:

The Roman officer who commanded the cavalry, Numonius Vala, rode off with his squadrons in the vain hope of escaping by thus abandoning his comrades. Unable to keep together or force their way across the woods and swamps, the horsemen were overpowered in detail and slaughtered to the last man…. Varus, after being severely wounded in a charge of the Germans against his part of the column, committed suicide to avoid falling into the hands of those whom he had exasperated by his oppressions. One of the lieutenant generals of the army fell fighting; the other surrendered to the enemy. But mercy to a fallen foe had never been a Roman virtue, and those among her legions who now laid down their arms in hope of quarter drank deep of the cup of suffering, which Rome had held to the lips of many a brave but unfortunate enemy. The infuriated Germans slaughtered their oppressors with deliberate ferocity, and those prisoners who were not hewn to pieces on the spot were only preserved to perish by a more cruel death in cold blood.

Only a tiny handful of Romans escaped from the Teutoburger Forest to carry the news of the catastrophe back to the Roman forts on the other side of the Rhine. Varus’ legions had been the pick of Rome’s army, and their destruction broke the back of the Roman imperium east of the Rhine.

A furious German populace rose up and exacted a grisly vengeance on Roman judges, Jewish speculators and slave dealers, and the civil servants Augustus had sent to administer the conquered territories. The two Roman legions remaining in Germania Magna were able to extricate themselves to Gaul only after hard fighting and severe losses.

The tidings struck Rome like a thunderclap of doom. The aged Augustus felt his throne tremble. He never fully recovered from the shock, and for months afterward he let his hair and beard grow, and was seen by his courtiers from time to time pounding his head in despair against the palace wall and crying out, “Oh, Varus, Varus, give me back my legions!”

Hermann’s great victory by no means ended the Roman threat to the Germans east of the Rhine, and many more battles were to be fought before Rome finally accepted, in 17 A.D., the Rhine and the Danube as a boundary between Roman and German territory. Clearly, though, that September day in 9 A.D. is a watershed of world history; the battle of the Teutoburger Forest is one of the half-dozen most decisive events in the history of the White race. Had Hermann lost that day to Varus, or had the conservatives among the Germans succeeded in aborting or betraying his revolution, the heart of Germany would have been Romanized. The land of the Angles and the Saxons and the Goths would have been permanently open, as was Rome, to the filth of the Levant: to Oriental customs and religion; to the mercantile spirit which places monetary gain above all else in life; to the swart, curly-haired men who swarmed in the marketplaces of the Mediterranean world, haggling over the interest on a loan or the price of a blond slave girl.

The Nordic spirit, the Faustian spirit, which is the unique possession of that race which burst into Europe from the eastern steppes more than 6,000 years ago; the spirit which carried Greece to the heights and impelled the earliest Romans to impose a new order on the Italian peninsula; the spirit which had eventually succumbed to racial decay in the south and which had been crushed out of the Celts of Gaul and Britain—that spirit would also have been crushed out of the Germans and replaced by the spirit of the lawyers and the moneychangers.

The fact that that spirit survived in the Germans, that it thrived again in Britain after the Saxon conquest, that it lived in the Vikings who sailed their dragon ships across the Atlantic to the New World five centuries after that, that after another ten centuries it carried our race beyond the bounds of this planet—is due in very large measure to the passion, energy, skill, and courage of Hermann the Cheruscer.

Arminius says goodbye to Thusnelda. Johannes Gehrts (1884)

Arminius says goodbye to Thusnelda. Johannes Gehrts (1884)

Four hundred years were yet to pass and a great deal more German blood shed before the German ascendancy over Rome became final and irreversible, but the events of 9 A.D. presaged everything which followed. After Hermann’s mighty feat the decaying Roman Empire was almost continuously on the defensive rather than the offensive. Although the southwestern corner of Germania Magna, encompassing the headwaters of the Rhine and the Danube (the area which had been abandoned by the Marcomanni prior to the Hermannschlacht), was later colonized by Rome; and although Emperor Trajan added the trans-Danubian province of Dacia to Rome’s possessions at the beginning of the second century, no really serious program of conquest of German lands was again attempted.

The German unity which Hermann forged did not last long, unfortunately. Although he outmaneuvered his rival Marbod, who was forced to seek Roman protection, Hermann himself lost his life to an assassin a few years later. Traditional intertribal rivalries and jealousies came to the fore again. Just as Roman decadence prevented the Romans from conquering the Germans in the ensuing decades, so did German disunity prevent the reverse.

The following is my abridgement of chapter 17 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Migrating Germans, Invading Huns,

Expanding Slavs Destroyed Roman Order

Hun Horde Routed Goths, Burst into Central Europe

Attila Yields to Gothic Valor; Germans Drive Asiatics from Europe

The Gothic nation, as was mentioned in the previous installment, had established itself on the southern shore of the Baltic, around the mouth of the Vistula, before 300 B.C. Prior to that the Goths had lived in southern Sweden.

Like the other Germans of their time, the Goths were tall, sturdily built, and Nordic in coloration, with blue or grey eyes and hair colors ranging from red to almost white. Roman reports describe them as the tallest of the Germans, with especially large hands and feet—perhaps a trait resulting from the local mixture of Indo-European and Cro-Magnon races in Sweden.

Soon they were also the richest of the Germans. In direct contact with the amber-gathering Baltic tribes to the east, the Goths monopolized the amber trade. For centuries Gothic caravans loaded with furs and amber pushed southward to sell their goods in the trading centers of the Roman Empire.

Gothic Migration. Then, in the third quarter of the second century of the present era, during the reign of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the Goths began a general movement to the southeast. Hundreds of thousands of them, taking their families, their cattle, and all their household goods, marched back toward the ancient Indo-European homeland their ancestors had left thousands of years earlier.

The Goths west of the Dniester—the Visigoths—moved down into the Danubian lands west of the Black Sea, where they inevitably came into conflict with the Romans. They conquered the Roman province of Dacia for themselves, after defeating a Roman army and killing a Roman emperor (Decius) in the year 251.

Toward the end of the third century, during the reign of Diocletian, the Empire was divided into eastern and western halves, for administrative and military purposes. The progressive breakdown of communications led eventually to separate de facto powers, one centered in Rome and the other in Byzantium (later renamed Constantinople).

During the first three-quarters of the fourth century, despite occasional raids, a state of relatively peaceful coexistence between Goths and Romans pervaded. Especially in the eastern half of the Empire, diplomacy and bribery were used to hold the Goths at bay. During the reign of Constantine (306-337) 40,000 Goths were recruited into the Roman army, and they thenceforth were the bulwark of the Eastern Empire.

It was in the reign of Emperor Valens, in the year 372, that the greatest menace to the White race, both Germans and Romans, since the beginning of recorded history suddenly appeared on the eastern horizon. From the depths of Central Asia a vast horde of brown-skinned, flat-nosed, slant-eyed little horsemen—fast, fierce, hardy, bloodthirsty, and apparently inexhaustible in numbers—came swarming across the steppe around the north end of the Caspian Sea. They were the Huns.

The first to feel their impact were the Alans, living south of the Don between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The Hunnic horde utterly crushed the Alans, some of whose remnants retreated southward into the Caucasus Mountains, while others fled westward in confusion, seeking refuge among the Goths. In the Caucasus today traces of the Nordic Alans are found in the Ossetes, whose language is Indo-European and who are taller and lighter than the Caucasic-speaking peoples around them.

End of the Ostrogoths. Next the Huns fell upon the Ostrogoths and routed them. The aged Ostrogothic king, Hermanric, slew himself in despair, and his successor, Vitimer, was killed in a vain effort to hold back the Brown flood. The Ostrogothic kingdom disintegrated, and its people streamed westward in terror, with the Huns at their heels.

Athanaric, king of the Visigoths, posted himself at the Dniester with a large army, but the Huns crossed the river and defeated him, inflicting great slaughter on his army.

Thus, the Visigoths too were forced to retreat westward. Athanaric petitioned Valens for permission for his people to cross the Danube and settle in Roman lands to the south. Valens consented, but he attached very hard conditions, which the Goths, in their desperation, were forced to accept: they were required to surrender all their weapons and to give up their women and children as hostages to the Romans.

The Goths crossed the Danube in 376 and settled in the Roman province of Lower Moesia, which corresponds roughly to modern Bulgaria. There the Romans took shameful advantage of them. Roman-Jewish merchants, in return for grain and other staples, took the hostage children of the Goths as slaves.

The Goths secretly rearmed themselves and rose up. For two years they waged a war of revenge, ravaging Thrace, Macedonia, and Thessaly. Finally, on August 9, 378, in the great battle of Hadrianople, the Gothic cavalry, commanded now by Fritigern, annihilated Valens’ infantry (most of whom were also Goths), and the emperor himself was killed. This was the worst defeat Rome had suffered since the Goths defeated and killed Decius 127 years earlier, and the battle decisively changed the conduct of future wars. Heretofore, Roman infantry tactics had been considered unbeatable, but Fritigern’s Goths had shown what heavy cavalry could do to infantry unprotected by its own cavalry.

The emperor of the eastern half of the Empire who succeeded Valens took a much more conciliatory stance toward the Goths, and they were confirmed in their possession of much of the territory south of the Danube which they had seized between 376 and 378. The Huns, meanwhile, had occupied Gothic Dacia (presentday Romania), as well as all the lands to the east.

Loss of a Homeland. The ancient homeland of the Nordic race was now in the hands of non-Whites.

For more than four millennia wave after wave of White warriors had come out of the eastern steppe to conquer and colonize Europe: Achaeans, Dorians, Latins, Celts, Germans, Balts, Slavs, Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, and uncounted and unnamed peoples before all these. But the Sarmatians were the last; after the Huns drove them and the Goths out, no other White barbarians were to come riding out of the east.

For the next thousand years the eastern steppe which had been the breeding ground of the Nordic race became the invasion route into Europe for periodic waves of non-White hordes from Asia: Huns, Avars, Turks, Magyars, Mongols.

The Huns contented themselves, for the time being, with that portion of Europe between the Carpathians and the Danube, leaving the Romans and the Germans elsewhere to their own devices. Rome, a hollow shelf peopled largely by Levantines and ruled in effect by a gaggle of filthy-rich Middle Eastern moneylenders, speculators, and merchants, depended for her continued existence upon cleverness and money rather than real strength. Germans menaced her and Germans defended her, and the Romans concentrated their energies on playing German off against German.

The game succeeded in the Eastern Empire, more or less, but not in the Western Empire. A Frank, Arbogast, was the chief adviser—and effective master—of Western Emperor Eugenius in the year 394, having assassinated Eugenius’ predecessor. The emperor of the East, Theodosius, sent his Gothic army against Arbogast, and Arbogast called on his fellow Franks for support. The two German armies fought at Aquileia, near modern Venice, and the Goths defeated the Franks.

Alaric the Bold. Two of the leaders of Theodosius’ army were Alaric the Bold, a Gothic prince, and Stilicho, a Vandal. After the battle of Aquileia Stilicho, nominally subordinate to Theodosius, became the effective master of the Western Empire. Alaric was chosen king of the Visigoths by his tribe and decided to challenge Stilicho, but as long as Stilicho lived he was able to hold Alaric at bay.

The emasculated and Levantinized Romans, unable to face the Germans man to man, bitterly resented their German allies as much as they did their German enemies. This resentment, born of weakness and cowardice, finally got the better of the Romans in 408, and they conspired to have their protector, Stilicho, murdered. Then the Romans in all the Italian cities butchered the wives and children of their German allies—60,000 of them.

This foolish and brutal move sent Stilicho’s German soldiers into Alaric’s arms, and Italy was then at the Goth’s mercy. Alaric’s army ravaged large areas of the peninsula for two years in revenge for the massacre of the German families. Alaric demanded a large ransom from the Romans and forced them to release some 40,000 German slaves.

Fall of Rome. Then, on the night of August 24, 410, Alaric’s Goths took Rome and sacked the city. This date marked, for all practical purposes, the end of the capital of the world. Rome had endured for 1,163 years and had ruled for a large portion of that time, but it would never again be a seat of power. For a few more decades the moribund Empire of the West issued its commands from the fortress city of Ravenna, 200 miles north of Rome, until the whole charade was finally ended in 476. The Empire of the East, on the other hand, would last another thousand years.

Fall of Rome. Then, on the night of August 24, 410, Alaric’s Goths took Rome and sacked the city. This date marked, for all practical purposes, the end of the capital of the world. Rome had endured for 1,163 years and had ruled for a large portion of that time, but it would never again be a seat of power. For a few more decades the moribund Empire of the West issued its commands from the fortress city of Ravenna, 200 miles north of Rome, until the whole charade was finally ended in 476. The Empire of the East, on the other hand, would last another thousand years.

The Huns, meanwhile, had not long contented themselves with Dacia, but had begun expanding westward again, wreaking such havoc that whole nations uprooted themselves and fled as the Huns advanced. The Vandals, a German people closely related to the Goths; the Alans who had been driven westward from the Transcaucasian steppe; and the Suebians poured across the Rhine into Gaul in 406, setting still other German nations, such as the Franks, Burgundians, and Alamanni, into motion.

Attila, King of the Huns. The Huns halted their westward push for more than 40 years while they consolidated their hold on all of central and eastern Europe, and on much of northern Europe as well. In 433 they gained a new king, whose name was Attila. In 445, when Attila established his new capital at Buda, in what is now Hungary, the empire of the Huns stretched from the Caspian Sea to the North Sea.

In 451 Attila began moving west again, with the intention of seizing Gaul and then the rest of the Western Empire. His army consisted not only of Huns but also of contingents from all the conquered peoples of Europe: Ostrogoths, Gepids, Rugians, Scirians, Heruls, Thuringians, and others, including Slavs.

One contingent was made up of Burgundians, half of whom the Huns had subjugated (and nearly annihilated) in 436. The struggle between the Burgundians and the Huns forms the background for the German heroic epic, the Nibelungenlied.

Attila’s mixed army threw western Europe into a state of terror as it advanced. So great was the devastation wrought on the countryside that Attila was given the nickname “the Scourge of God,” and it was said that grass never again grew where his horse had trod.

Two armies, one commanded by Aetius, the last of the Western Empire’s Roman generals, and the other by Theodoric, King of the Visigoths, rode against Attila. Aetius and Theodoric united their armies south of the Loire, in central Gaul, and compelled Attila to withdraw to the north-east.

Attila carefully chose the spot to halt his horde and make his stand. It was in a vast, open, and nearly level expanse of ground in northeastern France between the Marne and the Seine, where his cavalry would have ideal conditions for maneuvering. The region was known as the Catalaunian Plains, after the Catalauni, a Celtic people.

In a furious, day-long battle frightful losses were inflicted on both sides, but the Visigoths, Franks, free Burgundians, and Alans of Aetius and Theodoric had gained a decisive advantage over the Huns and their allies by nightfall. Attila retreated behind his wagons and in despair ordered a huge funeral pyre built for himself. He intended neither to be taken alive by his foes nor to have his corpse fall into their hands.

King Theodoric had fallen during the day’s fighting, and the command of the Visigothic army had passed to his son, Thorismund. The latter was eager to press his advantage and avenge his father’s death by annihilating the Hunnic horde.

The wily Roman Actius, however, putting the interests of his dying Empire first, persuaded Thorismund to allow Attila to withdraw his horde from Gaul. Aetius was afraid that if Thorismund completely destroyed the power of the Huns, then the Visigoths would again be a menace to the Empire; he preferred that the Huns and the Visigoths keep one another in check.

Attila and his army ravaged the countryside again, as they made their way back to Hungary. The following year they invaded northern Italy and razed the city of Aquileia to the ground; those of its inhabitants who were not killed fled into the nearby marshes, later to found the city of Venice.

But in 453 Attila died. The 60-year-old Hun burst a blood vessel during his wedding-night exertions, following his marriage to a blonde German maiden, Hildico (called Kriernhild in the Nibelungenlied). The Huns had already been stripped of their aura of invincibility by Theodoric, and the death of their leader diminished them still further in the eyes of their German vassals.

The latter, under the leadership of Ardaric the Gepid, rose up in 454. At the battle of the Nedao River in that year it was strictly German against Hun, and the Germans won a total victory, completely destroying the power of the Huns in Europe.

The vanquished Huns fled eastward, settling finally around the shores of the Sea of Azov in a vastly diminished realm. They left behind them only their name, in Hungary. Unfortunately, they also left some of their genes in those parts of Europe they had overrun. But in eighty years they had turned Europe upside down. Entire regions were depopulated, and the old status quo had vanished.

The following is my abridgement of chapter 18 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Christianity Spreads from Levant

to Dying Roman Empire,

then to Conquering Germans

Germans ‘Aryanize’ Christian Myths,

but Racially Destructive Ethics Retained

During the turbulent and eventful fifth century the Germans largely completed their conquest of the West. In the early years of that century German tribesmen, who had been raiding the coast of Roman Britain for many years, began a permanent invasion of the southeastern portion of the island, a development which was eventually to lead to a Germanic Britain.

In 476 Odoacer, an Ostrogothic chieftain who had become a general of Rome’s armies, deposed the last Roman emperor and ruled in his own name as king of Italy. Meanwhile the Visigoths were expanding their holdings in Gaul and completing their conquest of Spain, except for the northwestern region already held by their Suebian cousins and an enclave in the Pyrenees occupied by a remnant of the aboriginal Mediterranean inhabitants of the peninsula, the Basques.

And throughout the latter part of the century the Franks, the Alemanni, and the Burgundians were consolidating their own holds on the former Roman province of Gaul, establishing new kingdoms and laying the basis for the new European civilization of the Middle Ages. Everywhere in the West the old, decaying civilization centered on the Mediterranean gave way to the vigorous White barbarians from the North.

Oriental Infection. But the Germans did not make their conquest of the Roman world without becoming infected by some of the diseases which flourished so unwholesomely in Rome during her last days. Foremost among these was an infection which the Romans themselves had caught during the first century, a consequence of their own conquest of the Levant. It had begun as an offshoot of Judaism, had established itself in Jerusalem and a few other spots in the eastern Mediterranean area, and had traveled to Rome with Jewish merchants and speculators, who had long found that city an attractive center of operations.

It eventually became known to the world as Christianity, but for more than two centuries it festered in the sewers and catacombs of Rome, along with dozens of other alien religious sects from the Levant; its first adherents were Rome’s slaves, a cosmopolitan lot from all the lands conquered by the Romans. It was a religion designed to appeal to slaves: blessed are the poor, the meek, the wretched, the despised, it told them, for you shall inherit the earth from the strong, the brave, the proud, and the mighty; there will be pie in the sky for all believers, and the rest will suffer eternal torment. It appealed directly to a sense of envy and resentment of the weak against the strong.