The following is my abridgement of chapter 23 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Jew vs. White: More than 3,000 Years of Conflict

Jewish Religion Holds Jews To Be “Chosen” as Rulers of World

Jewish Leaders Find Hatred Necessary

There Can Be No Peace Between Predator and Prey

The purpose of this series of historical articles is the development of a fuller knowledge and understanding of the White past in its readers, in the hope that these things will in turn lead to a stronger sense of White identity and White solidarity. Other races—Arabs, Mongols, Amerinds, Negroes, and the rest—have come into the story only to the extent that they have interacted with Whites and influenced the White destiny. One can turn to other sources for more information on them.

There is one alien race, however, which has exerted such a strong influence on the White destiny since Roman times—and especially during the past century—and which poses such an overwhelming threat to that destiny today that it deserves special treatment.

That race—which in the taxonomic sense is not a true race at all, but rather a racial-national-ethnic entity bound together partly by ties of blood; partly by religion; partly by common traditions, customs, and folkways; and wholly by a common sense of identity and perceived common interests—is, of course, the Jewish race.

Desert Nomads. In early Neolithic times the ancestors of the Jews shared the Arabian peninsula with their Semitic cousins, the Arabs, and presumably were indistinguishable from them. Desert nomads like the other Semites, they gained their sustenance from their herds of camels, sheep, and goats.

In the first half of the second millennium B.C. the first written references to the Jews appeared, the consequence of their contacts with literate peoples in Egypt and Mesopotamia during their roamings. The reviews were uniformly unfavorable.

In a research paper published this year, for example, the noted Egyptologist, Professor Hans Goedicke, chairman of the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Johns Hopkins University, associates an inscription on an Egyptian shrine of the goddess Pakht, dated to the 15th century B.C., with the departure of the Jews of Egypt which is fancifully related in the Old Testament’s Book of Exodus. The inscription reads, in part: “And when I allowed the abomination of the gods to depart, the earth swallowed their footsteps.”

The Egyptians had reason enough to consider their departing Jewish guests “the abomination of the gods,” if there is any truth in the Biblical description of the Jews’ sojourn in Egypt. In the Book of Genesis the Jewish narrator boastfully tells of his fellow tribesmen’s takeover of the Egyptian economy and virtual enslavement of the Egyptian farmers and working people through the sort of financial chicanery which still seems to be their principal stock in trade today: When Joseph, the son of Israel (Jacob), became “ruler over all the land of Egypt” after gaining a corner on the local commodities market, he invited all his relatives in to “eat the fat of the land.” (Genesis 41-45)

But eventually, according to the first chapter of the Book of Exodus, there ascended the throne of Egypt a new pharaoh “who knew not Joseph” and who liberated the country from the grip of the Jewish moneylenders and grain brokers, eventually driving them from Egypt.

So the Egyptians may have been “prejudiced”—but, then, so was everyone else. The great Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (ca. 55-117 A.D.) wrote: “When the Assyrians, and after them the Medes and Persians, were masters of the Oriental world, the Jews, of all nations then held in subjection, were deemed the most contemptible.” (Histories, book 5, chapter 8)

Jewish Invasion of Palestine. The Jews first came into contact with Whites in the Middle East no later than the 12th century B.C., during the Jewish migration into Philistia (Palestine). The Philistines themselves, an Indo-European people, had invaded the area and conquered the native Canaanites only a few years before the Jews arrived (see the 11th installment in this series for a narrative of the Philistine-Jewish conflict).

In later centuries the Jews spread beyond Palestine into all the corners of the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern world, in part by simply following their mercantile instincts and in part as a consequence of their misfortunes in war. In the eighth century B.C. they were conquered by the Assyrians, who deported some 27,000 of them, and in the sixth century by the Babylonians, who hauled another batch of them away. It was during these forcible dispersions that the Jews’ view of themselves as a “chosen people,” infinitely superior to their conquerors, first stood them in good stead by helping them maintain their solidarity.

Esther Turns a Trick. The sort of resentment and hostility which the Jews generate among their Gentile hosts by behavior based on the deep-seated belief that the world is their oyster is illustrated well by the Old Testament tale of Esther. Set in the fifth century B.C., it suggests that the Persians of that era had already had their fill of Jewish arrogance and pushiness and wanted badly to get rid of their Semitic guests.

The Jewish response to Persian anti-Semitism was to slip a Jewish prostitute into the palace of the Persian king, concealing her Jewishness until she had used her bedroom skills to win the king’s favor and turn him against his own nobles. The ensuing slaughter of 75,000 Persian noblemen described in the Book of Esther is probably a figment of the Jewish imagination, but it is nevertheless still celebrated with glee and gloating, more than 2,400 years after the event, by Jews around the world in their annual Purim festival.

Unfortunately, later massacres instigated or perpetrated by the Jews against their non-Jewish hosts in response to anti-Semitism were all too real. The great English historian Edward Gibbon describes some of these which took place in the first and second centuries A.D.:

From the reign of Nero (54-68) to that of Antoninus Pius (138-161) the Jews discovered a fierce impatience of the dominion of Rome, which repeatedly broke out in the most furious massacres and insurrections.

Humanity is shocked at the recital of the horrid cruelties which they committed in the cities of Egypt, of Cyprus, and of Cyrene, where they dwelt in treacherous friendship with the unsuspecting natives, and we are tempted to applaud the severe retaliation which was exercised by the arms of the legions against a race of fanatics, whose dire and credulous superstition seemed to render them the implacable enemies not only of the Roman government but of human kind.

In Cyrene they massacred 220, 000 Greeks; in Cyprus 240,000, in Egypt a very great multitude. Many of these unhappy victims were sawn asunder, according to a precedent to which David had given the sanction of his example. The victorious Jews devoured the flesh, licked up the blood, and twisted the entrails like a girdle round their bodies. (History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, chapter XVI)

Actually, very little of humanity is shocked at the recital of these Jewish atrocities today, for the simple reason that the carefully laundered “approved” textbooks used in the schools omit any mention of them. Instead, humanity is treated to one television “documentary” after another, from “Holocaust” to “Masada,” in which the blameless, longsuffering Jews are “persecuted” by their enemies.

When one looks at all of Jewish history from the time of the Egyptian sojourn to the present, the outstanding feature which emerges is its endless series of cycles, each consisting of a period of increasingly arrogant and blatant depredations by the Jews against their hosts, followed by a period of reaction, in which either the exasperated Gentiles slaughter, drive out, and otherwise “persecute” the Jewish offenders; or the Jews manage to get the drop on their hosts instead and arrange a slaughter of Gentiles; or both.

Dual Existence. Indeed, this feature of Jewish history is not only outstanding, it is essential: without it the Jews would have ceased to exist by Roman times, at the latest. For the Jews are a unique people, the only race which has deliberately chosen a dual mode of national existence, dispersed among the Gentile nations from which they suck their sustenance and at the same time fiercely loyal to their center in Zion, even during the long periods of their history when Zion was only an idea instead of a sovereign political entity.

Without the diaspora the concrete Zion—i.e., the state of Israel—could not exist; and without the abstract Zion—i.e., the concept of the Jews as a united and exclusive whole, divinely ordained to own and rule the world—the diaspora could not exist.

Israel would not survive a year, were it not for the flow of “reparations” payments from West Germany, the billions of dollars in economic and military aid from the United States, and, most of all, the threat of armed retaliation by the United States against any Arab nation which actually makes a serious effort to dispossess the Jews of their stolen Arab territory.

It is certainly not love for the Jews on the part of the masses of Germans and Americans which maintains this support for Israel. It is instead a combination of two things: first, the enormous financial and political power of the Jews of the United States, the latter exercised primarily through the dominant Jewish position in the controlled news media; and second, the influence of a relatively small but vocal and well-organized minority of Jew-worshipping Christian fundamentalists, who accept at face value the Jews’ claim to be the divinely ordained rulers of the world.

And the diaspora would survive little more than a generation, were it not for the Jewish consciousness, the concept of Zion. It is this alone which keeps the dispersed Jews from becoming assimilated by their Gentile hosts, for the Jewish consciousness inevitably raises a barrier of mutual hatred between Jews and Gentiles.

How can a Jew of the diaspora, who is taught from the cradle that he belongs to a “chosen race,” do other than despise the goyim around him, who are not even considered human beings by his religious teachers? How can he do other than hate them for holding back him and his fellow Jews from the world dominion which he believes belongs rightfully to the Jewish nation? And how can Gentiles fail to sense this contempt and hatred and respond in kind?

Action and Reaction. In recapitulation, the dynamic of the interaction between Jew and Gentile is this: as soon as the Jews have infiltrated a Gentile land in sufficient numbers so that their organized efforts can be effective, they begin exploiting and manipulating. The more wealth and power they accumulate, the more brazenly and forcefully they attempt to accumulate still more, justifying themselves all the while with the reminder that Yahweh has promised it all to them anyway.

Any tendency to empathize or identify with their hosts is kept in check by a nonstop recitation of all the past wrongs the Gentile world has done them. Even before anti-Semitism exists in reality, it exists in the Jewish imagination: the Gentiles hate them, they believe, and so they must stick together for self-protection.

Sure enough, before the Jews’ solidarity has a chance to erode appreciably, the Gentiles are hating them. The Gentiles react to the Jews mildly at first and then with more and more resentment and energy as the Jewish depredations continue. It is this action-reaction combination, the hatred and counter-hatred, which keeps the Jews from being absorbed into the host nation.

Finally there is an explosion, and the most nimble Jews flee to begin the cycle over again in another Gentile land, while the slow ones remain to suffer the pent-up fury of their outraged hosts. The memory of this explosion is assiduously cultivated by the surviving Jews and becomes one more grudge they bear against the Gentile world. They still remember and celebrate the explosions of the Egyptians, the Persians, the Romans, and two dozen other Gentile peoples over the last 35 centuries or so, exaggerating their losses and embellishing the details every time in order to make the memories more poignant, while the Gentiles in each case forget within a generation or two.

These periodic outbursts against the Jews have actually served them doubly well: not only have they been invaluable in maintaining the Jewish consciousness and preventing assimilation, but they have also proved marvelously eugenic by regularly weeding out from the Jewish stock the least fit individuals. Jewish leaders, it should be noted, are thoroughly aware of the details of this dynamic. They fully recognize the necessity of maintaining the barrier of hatred between their own people and the rest of the world, just as they understand the value of an occasional explosion to freshen the hatred when assimilation becomes troublesome.

The blame for the decay of the Roman world has often been placed on the Jews. Indeed, some especially brazen Jewish writers have proudly accepted that blame and have even boasted that Christianity was invented deliberately by zealous Jews to further subvert and weaken the Roman Empire.

The truth of the matter, however, is that, so long as Roman society was healthy and the Roman spirit strong and sound, both were immune to Jewish malice and Jewish scheming. It was only after Rome was no longer Roman that the Jews were able to work their evil there.

After the old virtues had already been largely abandoned and the blood of the Romans polluted by that of a dozen races, the Jews, of course, did everything to hasten the process of dissolution. They swarmed over decaying Rome like maggots in a putrefying corpse, and from there they began their infiltration of the rest of Europe.

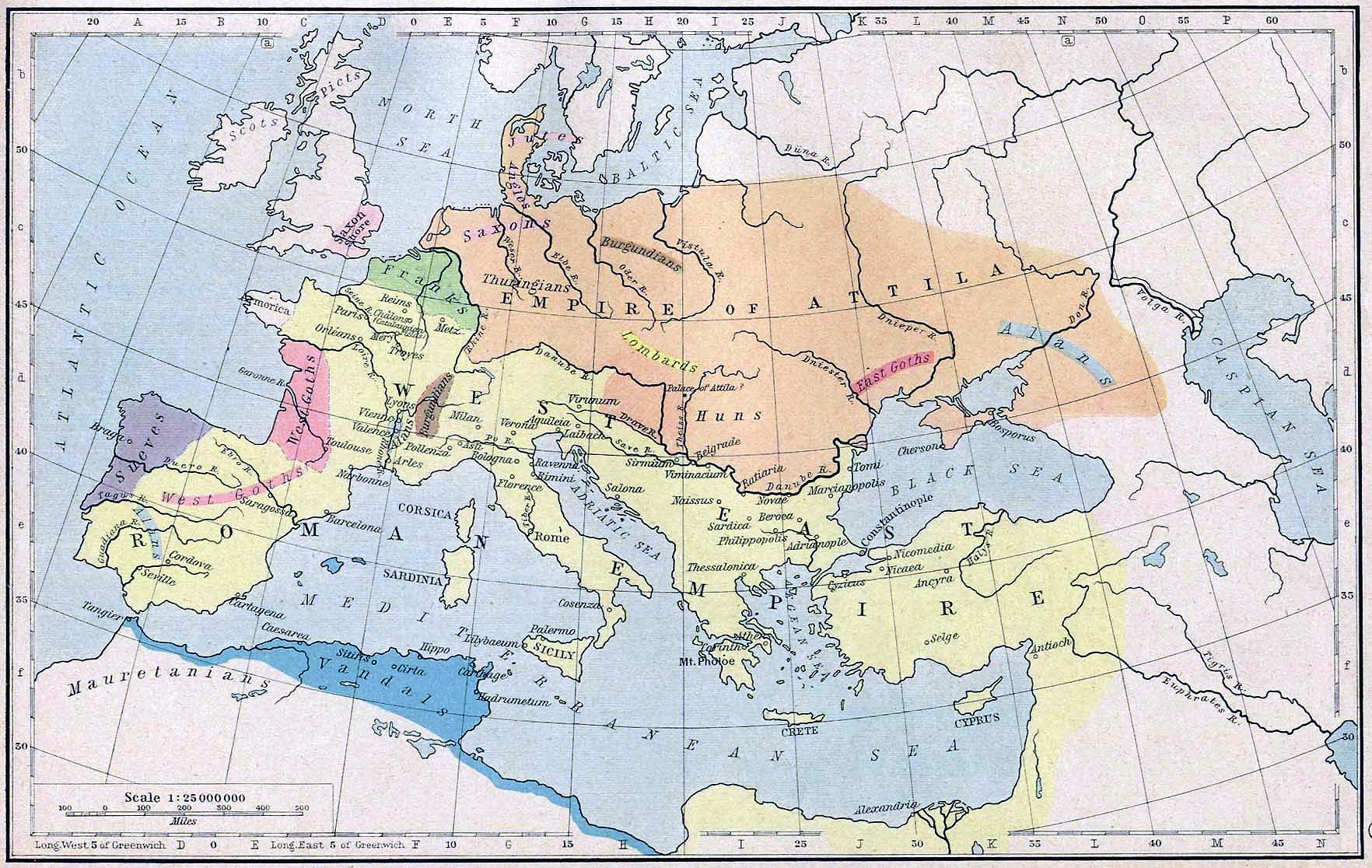

Thus, the Jews established themselves in every part of Europe over which Rome claimed dominion, and, wherever they could, they remained after that dominion ended. Except in the Mediterranean provinces and in Rome itself, however, their numbers remained relatively small at first.

Despising farming and all other manual activity, they engaged almost exclusively in trade and finance. Thus, their presence was confined entirely to the towns, and even a relatively large commercial center of 10 or 15 thousand inhabitants might have no more than a few dozen Jews.

Even their small numbers did not prevent nearly continuous friction between them and their Gentile neighbors, however. As Europe’s population, commerce, industry, and wealth grew during the Middle Ages, so did the numbers of Jews everywhere and with them the inevitable friction.

Everyone has heard of the wholesale expulsions of Jews which occurred in virtually every country of Europe during the Middle Ages: from England in 1290, from Germany in 1298, from France in 1306, from Lithuania in 1395, from Austria in 1421, from Spain in 1492, from Portugal in 1497, and so on. What many do not realize, however, is that the conflict between Jew and Gentile was not confined to these major upheavals on a national scale. Hardly a year passed in which the Jews were not massacred or expelled from some town or province by an exasperated citizenry. The national expulsions merely climaxed in each case a rising popular discontent punctuated by numerous local disturbances.

Bred to Business. In addition to the benefits of racial solidarity, the Jews were probably better businessmen, on the average, than their Gentile competitors. The Jews had been bred to a mercantile life for a hundred generations. The result was that all the business—and all the money—of any nation with a Jewish minority tended to gravitate into the hands of the Jews. The more capital they accumulated, the greater was their advantage, and the easier it was to accumulate still more.

Of course, the Jews were willing to share their wealth with their Gentile hosts—for a price. They would gladly lend money to a peasant, in return for a share of his next crop or a lien on his land; and to a prince, in return for a portion of the spoils of his next war. Eventually, half the citizens of the nation were hopelessly in debt to the Jews.

Such a state of affairs was inherently unstable, and periodic explosions were inevitable. Time after time princes and people alike found that the best way out of an increasingly tight financial squeeze was a general burning of the Jews’ books of account—and of the Jews too, if they did not get out of the country fast enough. The antipathy which already existed between Jews and Gentiles because of the Jews’ general demeanor made this solution especially attractive, as did the religious intolerance of the times.

One would think that one episode of this sort in any country would be enough for the Jews, and that they would thenceforth stay away from a place where they were so manifestly unwelcome. But they could not. Any country in Europe temporarily without a Jewish minority to soak up the country’s money like a sponge had an irresistible attraction for them. Before the embers of the last general Jew-burning were cool, other Jews were quietly sneaking in to take the place of the ones who had been slaughtered.

The great 19th-century Russian writer Nikolai Gogol embodied this extraordinary Jewish peculiarity in a character in his Taras Bulba, the story of a Cossack chieftain. The character, Yankel, is one of a group of Jewish, merchants and their dependents who have attached themselves to the Cossacks’ camp. One day the Cossacks rid themselves of the Jewish pests by throwing them all in the Dnieper and drowning them—all except Yankel, who hides beneath a wagon.

While the massacre is taking place, Yankel trembles in fear of being discovered. As soon as it is over and things have quieted down again, he creeps from his hiding place. The reader expects that Yankel will then waste no time putting as much distance between himself and the Cossacks as possible. But, no; Yankel instead rushes to set up a stall and begin selling gunpowder and trinkets to the men who have just drowned his kinsmen. His eagerness to resume business seems doubled by the fact that now he has no competitors.

The Jews were often able to ameliorate their situations greatly during the Middle Ages by establishing special relationships with Gentile rulers. They served as financial advisers and tax collectors for the princes of the realm and of the Church, always ready with rich bribes to secure the protection of their patrons when the hard-pressed common folk began agitating against them. They made themselves so useful to some rulers, in fact, that they were favored above Christian subjects in the laws and decrees of those rulers.

The Frankish emperor Charlemagne was one who was notorious for the favors and privileges he bestowed on the Jews, and his successor followed his example.

The medieval Church was at least as much at fault as the royalty in showing favor to the Jews. There were exceptions to the rule, however: several Church leaders heroically stood up for the common people and condemned the Jews for exploiting them. One of these was Agobard, a ninth-century bishop of Lyons.

Agobard lost his struggle with Louis, but his efforts had a long-range effect on the conscience of many of his fellow Franks. Despite the enormous financial power of the Jews and the protection their bribes bought them, they were continually overreaching themselves: whenever they were given a little rope, they eventually managed to hang themselves. No matter how much favor kings, emperors, or princes of the Church bestowed on them, the unrest their usury created among the peasants and the Gentile tradesmen forced the rulers to slap them down again and again.

The hatred between Jews and Gentiles was so intense by the 12th century that virtually every European country was obliged to separate the Jews from the rest of the populace. For their own protection the Jews retreated into walled ghettos, where they were safe from the fury of the Gentiles, except in cases of the most extreme unrest.

And for the protection of the Gentiles, Jews were obliged to wear distinctive clothing. After the Church’s Lateran Council of 1215, an edict forbade any Jew to venture out of the ghetto without a yellow ring (“Jew badge”) sewn on his outer garment, so that every Gentile he met could beware him.

But these measures proved insufficient, for they failed to deal with the fundamental problem: so long as the Jews remained Jews, there could be no peace between them and any other people.

Edward the Great. In England, for example, throughout the 13th century there were outbreaks of civil disorder, as the debt-laden citizens sporadically lashed out at their Jewish oppressors. A prominent Jewish historian, Abram Sachar, in his A History of the Jews (Knopf, 1965), tells what happened next:

At last, with the accession of Edward I, came the end. Edward was one of the most popular figures in English history. Tall, fair, amiable, an able soldier, a good administrator, he was the idol of his people. But he was filled with prejudices, and hated foreigners and foreign ways. His Statute of Judaism, in 1275, might have been modeled on the restrictive legislation of his contemporary, St. Louis of France. He forbade all usury and closed the most important means of livelihood that remained to the Jews. Farming, commerce, and handicrafts were specifically allowed, but it was exceedingly difficult to pursue those occupations.

Difficult indeed, compared to effortlessly raking in capital gains! Did Edward really expect the Jews in England to abandon their gilded countinghouses and grub about in the soil for cabbages and turnips, or engage in some other backbreaking livelihood like mere goyim? God’s Chosen People should work for a living?

Edward should have known better. Fifteen years later, having finally reached the conclusion that the Jews were incorrigible, he condemned them as parasites and mischief-makers and ordered them all out of the country. They were not allowed back in until Cromwell’s Puritans gained the upper hand 400 years later. Meanwhile, England enjoyed an unprecedented Golden Age of progress and prosperity without a Jew in the land.

Unfortunately, the other monarchs of Europe, who one after another found themselves compelled to follow Edward’s example, were not able to provide the same long-term benefits to their countries; in nearly every case the Jews managed to bribe their way back in within a few years.