The Bernaldine pages

La Santa Furia by C.T. Sr., my father, is a music composition in honor to Bartolomé de Las Casas for an orator, a soprano, three tenors, baritone, mixed chorus and orchestra, which at the moment of my writing still has to be premiered. Las Casas, whom my father greatly admires, wrote:

Into these meek sheep herd [the Amerindians], and of the aforesaid qualities by their Maker and Creator thus endoweth, there came the Spaniards who soon after behaved like cruel wolves, tigers and lions that had been starved for many days.

Las Casas is considered the champion of the indigenous cause before the Spanish crown. Those who condemn the Conquest take note of the investigation conducted against Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of New Spain, accused of having lined up several Indians during the Mixtón War and smashing them with cannon fire. As a child, an illustration piqued my interest in a Mexican comic, about some Indians attacked by the fearful dogs that the Spaniards had brought (there were no large dogs in pre-Columbian America). Motolinía reported that innumerable Indians entered healthy the mines only to come out as wrecked bodies. The slave work in the mines, the Franciscan tells us in Historia de los Indios de Nueva España, killed so many that the birds that fed from the human carrion “darkened the skies,” and let us not talk about the slavery in the Caribbean islands with which, originally, Las Casas had so intimate contact. In La Española (Santo Domingo), Cuba and other islands the native population was virtually exterminated, especially due to the epidemics the conquerors had brought. These and many other facts appalled Las Casas, and in his vast literary corpus the tireless friar always tried to expose the excesses of the Spanish conquest.

English- and Spanish-speaking liberals are fond of quoting Las Casas. But was he right? In contrast to another friar, Diego de Landa, Las Casas always omitted speaking out about the cruelties that the Indians committed against themselves. In fact, Las Casas is often accused for having originated the Black Legend. For example, his quotation cited above is a lie: the Mesoamericans were everything except “meek sheep.” While the conquest was a calamity for many Indians, it benefited many others. Only thanks to it the children would not receive anymore the schizogenic shock of learning that their folk had sacrificed, and sometimes eaten in a glamorous party, one of their little siblings. In his role of spiritual adviser, Las Casas wrote a biased and polemical sermon, A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, as well as more scholarly texts, to force Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, to take the necessary measures in favor of the natives. His goal was to protect them before the trendy scholastic doctrine that they were born slaves.

In the 1930s and ’40s Harvard historian Lewis Hanke found as fascinating the figure of Las Casas as my father would do in more recent times. After reading a magnificent book by Hanke, that my father himself lent me from his library, I could not avoid comparing Las Casas to the anthropologists who have kept secret the cruelty of the aboriginals in their eagerness to protect them. A single example will illustrate it. Las Casas went so far as defending the indigenous cannibalism with the pretext that it was a religious custom, which Las Casas compared to the Christian communion. It seems strange to tell it, but the first seeds of cultural relativism, an ideology that would cover the West since the last decades of the twentieth century, had been sown in the sixteenth century.

The Mexicas had only been the last Mesoamericans providers of an immense teoatl: a divine sea, an ocean of poured-out blood for the gods. Just as the pre-Hispanic aboriginals of the Canary Islands, the Olmecs performed sacrifices with a fatal whack on the head. Of the Mayas, so idealized when I was a boy, it is known much more. They were the ones who initiated the practice of caging the condemned before sacrificing them and, after the killing, throwing the bodies down from the pyramids. In 1696, with the eighteenth century coming up, the Mayas sacrificed some unwary missionaries who dared to incursion into a still unconquered region. When I visited the ruins of Palenque I went up its pyramid and down through the internal steps surrounded by a warm and humid weather, to the tomb of the famous sarcophagus of stone. I felt such place gloomy and inconceivable. I now remember an archaeologist in television talking about a drawing in a Maya enclosure: a hanged prisoner maintained alive in state of torment.

The Mayas treated more sadistically the prisoners than the Mexicas. Diego de Landa recounts that they went as far as torturing the captive kings by gouging their eyes out, chopping off their ears and noses and eating up their fingers. They maintained the poor captive alive for years before killing him, and the classic The Blood of the Kings tells us that the Mayas tore the jaw out from some prisoners still alive. Once more, not even Mel Gibson dared to film these atrocities, although he mentioned them during an interview when defending his film before the criticism of politically-correct reporters and academics. Unlike them, I agree with Gibson that the disappearance of such culture should not sadden us but rather revalue the European culture. And I would add that, when I see in a well-known television program a native English speaker rationalizing the Maya sacrifices, it is clear to me that political correctness in our times exemplifies what in psychology is known as “identification with the perpetrator.”

Both the Teotihuacans and the Tolteca-Chichimecas were bloodthirsty. The Tenochcas, who greatly admired them, killed and flayed a princess in the year 1300: an outrage that the indigenistas sweep under the rug since this and similar murders are related to the stories of the foundation of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. Like their ancestors, the Mexicas established wars which only purpose was to facilitate captives for the killing.

Let us tell the truth guilelessly: Mesoamerica was the place of a culture of serial killers. In the raids launched into foreign territory, sometimes called Flower Wars like the one seen in Apocalypto, the principal activity was oriented toward the sacrifice. In fact, it was impossible to obtain political power in that society without passing first through the business of the sacrifice. Preventing adolescents from cutting their nape hairlock unless they captured a victim for sacrifice conveyed a message: If you don’t collaborate with the serial killing you won’t climb up the social hierarchy.

An explosive catharsis and real furor was freed in the outbreak of war as the Amerindians sheltered something recondite that had to be discharged at all costs. In 1585 Diego Muñoz Camargo wrote in History of Tlaxcala that, accompanied by the immense shouting when rushing into combat, the warriors played “drums and caracoles [percussion sticks] and trumpets that made a strange noise and roar, and more than a little dreadfulness in fragile hearts.” The Anonymous Conqueror adds that during the fighting they vociferated the eeriest shrieks and whistling, and that after winning the war only the young women were spared. To contribute with live bodies for the thirsty gods, not the killing in situ, was the objective. Behind there came the specialized warriors who tied up the captives and transferred them to the stone altars.

With a stabbing which purpose was not to kill the victim, the sacrificer, usually the high priest of one of the innumerable temples, opened the victim’s body: a dull blow at the diaphragm level or on the chest. The sacrificer then stuck the hand into the viscera poking until finding the heart. Grabbed and still beating, he tore it out with a strong pull. This eventration and ablation of the heart is the form in which the sacrifice was practiced, in identical mode, thousands upon thousands of times in Mesoamerica. The last thing that the victim saw in the instant before losing consciousness were his executioners. By tearing out the heart in such a way the body poured out virtually all of its blood, from five to six liters: the strongest hemorrhage of all conceivable forms.

Diego Durán was startled that, according to his estimates, in the pre-Hispanic world more people died in the sacrifices than from natural death. In contrast to how the Second World War is taught to us, academics are reluctant to point out that the sacrificial institution in Mesoamerica was a true Holocaust. The year 1487 signaled the climax of the sacrificial thirst. In four consecutive days the ancient Mexicans indulged themselves in an orgy of blood. The warriors had taken men from entire tribes to be sacrificed during the festivities of the reconsecration of the last layer of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan. Through four days the priests, their assistants and the common citizens uninterruptedly tore out hearts on fourteen pyramids. The poured-out blood stained of red the plaza and the stone ramps that were constructed to throw the bodies down. The exact figure is unknown but the Codex Telleriano-Remensis tells that the old people spoke of 4000 sacrificed humans. It is probable that the propaganda of Mexica terror inflated the official figure to 84,400 sacrificed victims to frighten their rivals.

The 1487 reconsecration aside, we should not forget the perpetuity of the sacrificial Mexican holyday, except the feared five days at the end of the year. The blood of the victims was spilled like holy water (something of this can be seen beside Gibson’s vertical tzompantli). The reverberation of such a butchery reached the unconscious of the youth I was centuries after it. I will never forget a dream I had many years ago in which I saw myself transported to the gloomiest moment of a night in the center of the old Tenochtitlan. I remember the atmosphere of the dream: something told me, in that dense night, that there was an odor and a deposit of bodies that made my flesh creep for the inconceivable amount of human remains: a very close place where my soul wandered around. The horror of the culture was captured in the oneiric taste that is impossible to describe in words. The filthy stench of the place was something I knew existed, though I do not remember having smelled anything during the dream.

The second month of the Mexica calendar was called Tlacaxipehualiztli, literally “the flaying of the men,” during which only in Tenochtitlan at least seventy people were killed. Sometimes the condemned to be sacrificed were led naked covered with white chalk. The victims of Xippe Tótec, an imported god from the Yopi region of Guerrero-Oaxaca, had been presented to the public the previous month of the sacrifice. In Mesoamerican statuary Our Lord the Flayed One is always represented covered with the skin of a sacrificed victim, whose features can be guessed on Xippe’s skin. In that holiday, writes Duverger, the beggars were allowed to dress with the skins “still greasy with the victim’s blood” and they begged at the homes of Tenochtitlan “with that terrifying tunic.” According to the Florentine Codex, those who had captured the victims also wore the skins. After several days of using them “the stench was so terrible that everybody turned their heads; it was repulsive: people that encountered them covered their noses, and the skins already dry became crumbly.”

These offering acts were the opposite of the Hollywood images of a secret cult that, clandestinely, sacrifices a young woman. Mesoamerica was the theatre of the most public of the cruelties. In contrast to the Christian cathedrals which spirituality lies in a sensation of privacy and inwardness, the Mesoamerican temple showed off the sacrifice at the universal sight of the sun, and the average people participated in a communal event. In the holiday called Panquetzaliztli the dancers “ran at the top of their speed, jumped and shook until left breathless and the old people of the neighborhoods played music and sang for them.” The exhausting marathon was a hallucinating spectacle and the ritual murders marked the height of the Mexican party. In another of their celebrations, Xócotl huetzi, the celebration of the fire god, the victims were thrown over an immense brazier while the crowd contemplated speechless. Sahagún informs us that the Mexicans took them out of the brazier with their fleshes burnt and swollen, and that after their hearts were torn out “the people dispersed and everybody went to their homes to celebrate, since it was a day of great rejoicing.”

All sacrifice was surrounded by popular parties. Personally, what shocks me the most is the second month of the Mexica calendar, the month that I most relate to my dream, because in real life those who would be killed and skinned fainted, and in this panic-stricken state they were dragged by the hair to the sacrificial stone.

The priests also dressed themselves with the yellow-painted skins of the victims; the skin’s exterior turned inwards like a sock. Our Lord the Flayed One was invoked with these words: “Oh my god, why do you play too hard to get it? Put your golden vestments on, put them on!” The body of the flayed victim was cooked and shared out for its consumption. The Florentine Codex has illustrations of these forms of sacrifice, including an illustration of five Indians skinning a dead body. The xixipeme were the men who dressed themselves with the skin of the victims personifying the deity.

The evidence in both the codexes and on the mural paintings, steles, graffiti and pots are witness of the gamut of the human sacrifices. Even zealous indigenistas like Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Leonardo López Luján have stated publicly that there is iconographic evidence of the sacrifices in Teotihuacan, Bonampak, Tikal, Piedras Negras and on the codexes Borgia, Selden and Magliabechiano, as well as irrefutable physical evidence in the form of blood particles extracted from the sacrificial daggers.

A warrior and his captive, grabbed by the hair and crying (note the tears on the face). In addition to the extraction of the heart, in the last incarnation of this culture of serial killers the victims were locked up in a cave where they would die of thirst and starvation; or were decapitated, drowned, riddled with arrows, thrown from the precipices, beaten to death, hanged, stoned or burned alive. In the ritual called mitote, the still alive victims were bled while a group of dancers bit their bodies. The mitote culminated with the cooking and communal consumption of the victims in a stew similar to the pozole. In the sacrifice performed by the Matlazinca the victim was seized in a net and the bones slowly crushed by means of twisting the net. The ballgame, performed from the gulf’s coast and that aroused enormous passions among the spectators, culminated in the dragging of the decapitated body so that its blood stained the sand with a frieze of skulls “watching” the sport.

A warrior and his captive, grabbed by the hair and crying (note the tears on the face). In addition to the extraction of the heart, in the last incarnation of this culture of serial killers the victims were locked up in a cave where they would die of thirst and starvation; or were decapitated, drowned, riddled with arrows, thrown from the precipices, beaten to death, hanged, stoned or burned alive. In the ritual called mitote, the still alive victims were bled while a group of dancers bit their bodies. The mitote culminated with the cooking and communal consumption of the victims in a stew similar to the pozole. In the sacrifice performed by the Matlazinca the victim was seized in a net and the bones slowly crushed by means of twisting the net. The ballgame, performed from the gulf’s coast and that aroused enormous passions among the spectators, culminated in the dragging of the decapitated body so that its blood stained the sand with a frieze of skulls “watching” the sport.

There is no point in making a scholarly, Sahagunesque encyclopedia list, about the names of the gods or the months of the calendar that corresponded to each kind of these sacrifices. Suffice it to say that at the top of the pyramids the idols were of the size of a man and even larger, composed by a paste of floured seeds mixed with the blood of the sacrifices. The figures were sitting on chairs with a sword on one hand and a shield on the other. What I said above of the great Uichilobos could be told once more: how I would like to contemplate the figures of the so-called Aztec Pantheon. Sacrifices were performed to gods whose names are familiar for us who attended the Mexican schools: from the agrarian, war, water and vegetation deities to the gods of the death, fire and lust. Most of the time the sacrifices were performed on the temples, but they could be done in the imperial palace too. We already saw that children were sacrificed on mounts and in the lake. Now I must say something about the sacrifices of women. According to the Florentine Codex, during the rituals of the months Huey tecuíhuitl (from June 22 to July 11) and Ochpaniztli (from August 21 to September 9) women were deceived with these words:

Be merry my daughter, very soon you will share the bed of emperor Motecuhzoma. He will sleep with you, oh blessed one!

The Indian girl voluntarily walked up the temple’s steps but when she arrived she was decapitated by surprise. In similar sacrifices at the arranged time and date according to the calendar’s holiday, women were decapitated, flayed and their skins used like a trophy. Besides men, women, children and occasionally old people, the Mexicas sacrificed dogs, coyotes, deer, eagles and jaguars. The Florentine codex informs us that sometimes they went up the pyramid with the human victim tied up by the four extremities, “meaning they were like the deer.”

The writer who best transports us into this unheard-of world and who most reaches my dream of “machines to see the past” is Bernal Díaz del Castillo and his The Truthful History of the Conquest of New Spain. The spontaneous testimony of the infantry soldier differs from the dry reports by Cortés. It also differs, as a memorialist work, from the treatise that Hugh Thomas wrote half a millennium later, considered a standard reference about the conquest. It tells a lot about our primitive era to focus on the literary form of the Quixote, which is fiction, instead of the real facts that Bernal recounts: extraordinary experiences where he often was very close of losing his life. (The attitude of the people of letters reminds me precisely a passage of Cervantes’ novel: the hidalgo only lost his nerve when he run into the only real adventure he encountered, in contrast to his windmills.) The discovery of the Bernal chronicle impressed me considerably. His work was an eye-opener about the charlatanry in the Mexican schools with all of its silences, blindness and taboos about cannibalism and the cruelty and magnitude of the pre-Columbian sacrificial institution. It seemed inconceivable that I had to wait so long to discover an author that speaks like no other about the distant past of Mexico, someone whose writing I should have met in my adolescence. I am increasingly convinced that the true university are the books; and the voice of one’s own conscience, more than the voice of the academics, the lighthouse that guides us in the seas of the world.

Humboldt said that the joy experienced by the adventurer facing the newly discovered world was better transmitted by the chronicler than by the poets. In 1545 Bernal moved to the Old Guatemala, where he lived the rest of his life, although he would not write down his memories until he was close seventy. The Guatemalan poet Luis Cardoza y Aragón said that Bernal’s chronicle is the most important work about the conquest. He considers it superior to the chronicles of the military campaigns in Peru or the campaigns against Turkey, Flanders or Italy. Those who in more recent times have read Bernal in translations tell similar things. In an online book-review it can be read: “In every page of this book lies the plots and the characters for [every] single Spielberg movie. But no movie, no adventure, no science fiction, and no Goth novel can even come close to Bernal Diaz’s first-hand account of the initial defeat [of the Spaniards] and final conquest of New Spain.” And Christopher Bonn Jonnes, author of Wake up Dead, wrote: “This story might have been rejected as too far-fetched if it were offered as fiction, but it is history.”

Unlike the soporific scholarly treatises, in the Bernaldine pages one really feels how pre-Hispanic Mexico was. The narrative about the shock that the Europeans felt when running for the very first time in history with the sacrificial institution is very illustrative. It happened in an island near Veracruz. Due to the novelty that the ritual represented for Bernal and his comrades they baptized it Island of the Sacrifice.

And we found a worship house with a large and very ugly idol, called Tezcatepuca [Tezcatlipoca], with four Indians with very large dark cassocks as its companions, with capes like the ones of the Dominicans or the cannons. And they were the priests of that idol, commonly called in New Spain [the Aztec Empire] papas, as I have already mentioned. And that day they had sacrificed two boys with their opened chest, and their hearts and blood offered to that cursed idol. And we did not consent they gave us that odorous [offering] smoke; instead we felt great pity to see those two boys dead, and such a gigantic cruelty. And the general asked the Indian Francisco, already mentioned by me, whom we brought to the Banderas River and who seemed to know something, why they did it, and only by means of gestures, since by then we didn’t have any translator, as again I have said.

Those were the times before the Cortés expedition. In the Grijalva expedition, Bernal and his comrades had been the first Europeans to notice that beyond Cuba and La Española there were no more islands but immense lands. In the expedition after Gijalva’s, now way inland into the continent in what today is the state of Veracruz, Bernal tells us:

Pedro de Alvarado said they had found every dead body without arms and legs, and other Indians said that [the arms and legs] had been taken as food, about which our soldiers were amazed at such great cruelties. And let us stop talking of so many sacrifices, since from that town on we did not find anything else.

Let us also take a leap forward on the Bernaldine route to Tenochtitlan where they did not find anything else, Tlaxcala included. When they reached Cholula, a religious city of pilgrimage with a hundred of temples and the highest pyramid of the empire, dedicated to Quetzalcóatl, the Cholulans told Cortés:

“Look, Malinche [Marina’s master], this city is in bad mood. We know that this night they have sacrificed to their idol, which is the war idol, seven people and five of them were children, so that they give victory against you.”

For the ancient Mesoamericans everything was resolved through the killing of children and adults. Once the Spaniards reached the great capital of the empire, and after Moctezuma and his retinue conducted them in grand tour through the beautiful Tenochtitlan and having seen the impressive Uichilobos at the pyramid’s top, Bernal tells us:

A little way apart from the great Cue [pyramid] there was another small tower which was also an idol house or a true hell, for it had at the opening of one gate a most terrible mouth such as they depict, saying that such there are in hell. The mouth was open with great fangs to devour souls, and here too were some shapes of devils and bodies of serpents close to the door, and a little way off was a place of sacrifice all blood-stained and black with smoke, and encrusted with blood, and there were many great ollas and pitchers and large earthenware jars of water, for it was here that they cooked the flesh of the unfortunate Indians who were sacrificed, which was eaten by the papas. There were also near the place of sacrifice many large knives and chopping blocks, such as those on which they cut up meat in the slaughter-houses. […] I always called that place the house of hell.

Sahagún and Durán corroborate Bernal’s testimony about cannibalism. As we already saw, not even Bartolomé de Las Casas denied it. In History of Tlaxcala Diego Muñoz wrote:

Thus there were public butcher’s shops of human flesh, as if it were of cow or sheep like the ones we have today.

In the chapter XXIV authored by the Anonymous Conqueror it can be read that throughout Mesoamerica the natives ate human flesh that, the chronicler adds, they liked more than any other food. It is noteworthy that in this occasion the Mexicans did not use chili peppers, only salt: which according to the scholars suggest that they had it as precious delicatessen. Human flesh, which tasted like pig, was not roasted but served as pozole. In Tenochtitlan the bodies were taken to the neighborhoods for consumption. (Likewise, there were human flesh remnants in the markets of Batak in Sumatra before the Dutch conquest.) The one who made the capture during the war was the owner of the body when it reached the bottom steps of the pyramid. The priest’s assistants gave the owner a pumpkin full of warm blood of the victim. With the blood the owner made offerings to the diverse statues. The house of the capturer was the eating-place, but according to the etiquette he could not join the banquet.

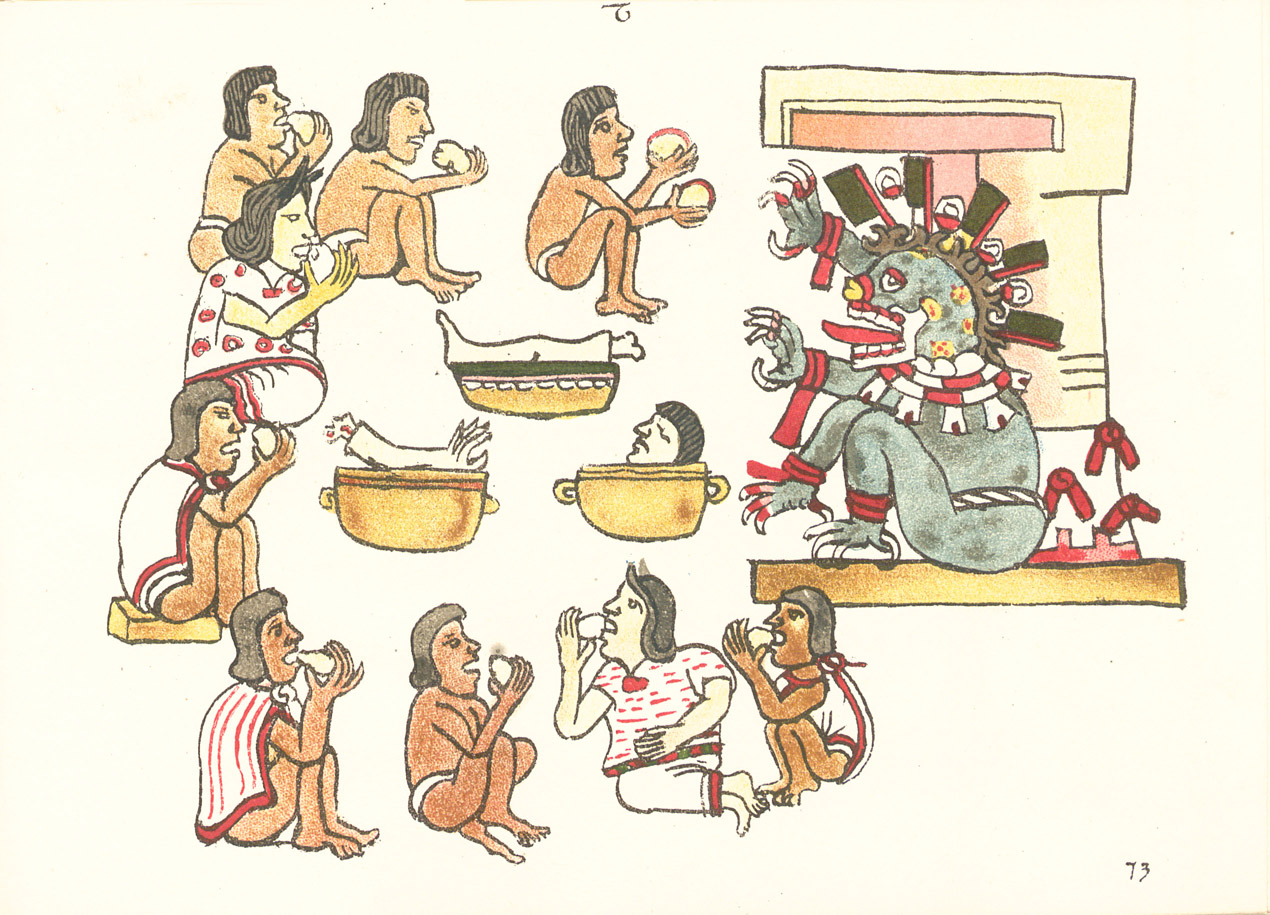

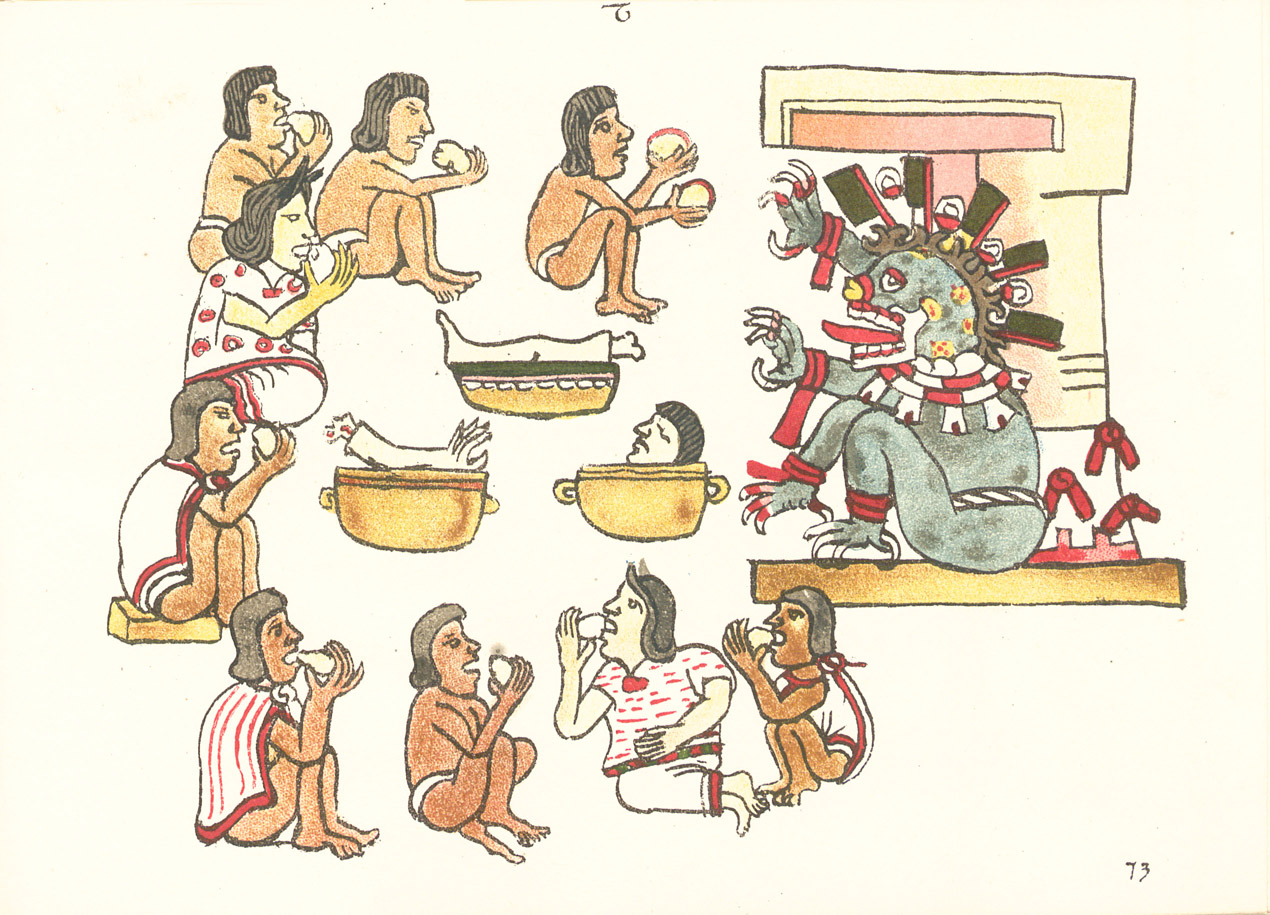

I have mentioned the festivities of the month Panquetzaliztli but did not said that, according to Sahagún, in that festivity the Mexicas bought slaves, “washed them up and gave them as gifts to be fed upon, so that their flesh was tasty when they were killed and eaten.” Even the contemporary writers who admire the Mexica world agree with Sahagún. For Duverger, cannibalism should not be disguised as a symbolic part of an ancient ritual: “No! Cannibalism forms part of the Aztec reality and its practice was much more widespread and considerably more natural than what it is sometimes presented.” He adds: “Let us open the codexes: arms and legs emerge from a pitcher placed on fire with curled up Indians who devour, by hand, the arms and legs of a sacrificed victim.”

(A scene of communal cannibalism: Codex Magliabechiano.) When the Tlaxcallans took the dead Tepeacas to the Tlaxcala butcher’s shops after the flight from Tenochtitlan, it is clear that the objective was not ritual cannibalism but the most pragmatic anthropophagy (this shows that Las Casas’s claim mentioned above that anthropophagy was a religious custom is simply untrue). Miguel Botella from the University of Granada explains that Mesoamerican cannibalism had been “like today’s bull fighting, where everything follows a ritual, but once the animal dies it is meat.” Botella points out that the chroniclers’ descriptions have been corroborated by examining more than twenty thousand bone-remains throughout the continent, some of them with unequivocal signs of culinary manipulation. Among the very diverse recipes of the ancient Mexicans, the one that I found most disgusting to imagine was an immense tamale they did with a dead Indian by grinding the remains—after a year of his death and burial!

(A scene of communal cannibalism: Codex Magliabechiano.) When the Tlaxcallans took the dead Tepeacas to the Tlaxcala butcher’s shops after the flight from Tenochtitlan, it is clear that the objective was not ritual cannibalism but the most pragmatic anthropophagy (this shows that Las Casas’s claim mentioned above that anthropophagy was a religious custom is simply untrue). Miguel Botella from the University of Granada explains that Mesoamerican cannibalism had been “like today’s bull fighting, where everything follows a ritual, but once the animal dies it is meat.” Botella points out that the chroniclers’ descriptions have been corroborated by examining more than twenty thousand bone-remains throughout the continent, some of them with unequivocal signs of culinary manipulation. Among the very diverse recipes of the ancient Mexicans, the one that I found most disgusting to imagine was an immense tamale they did with a dead Indian by grinding the remains—after a year of his death and burial!

After the massacre of Cholula the Spaniards liberated the captives from the wooden, cage-like jails that included children fed for consumption. Not even Hugh Thomas denies this. But the politically correct establishment always depicts the massacre of Cholula as one of the meanest acts by the Spaniards. They never mention the cages or how the captives were liberated thanks to the conquerors, sparing them from being eaten by the Cholulans.

However hard the nationalist Mexicans may try to palm this matter off from the school textbooks, and however hard it may seem to imagine it for those of us who were educated to idealize that culture, the ineludible fact is that only thirteen or fourteen generations ago the Mexicans consumed human flesh as part of their food chain.

___________

The objective of the book is to present to the racialist community my philosophy of The Four Words on how to eliminate all unnecessary suffering. If life allows, next time I will reproduce here the section on Aztec childrearing. Those interested in obtaining a copy of Day of Wrath can request it: here.