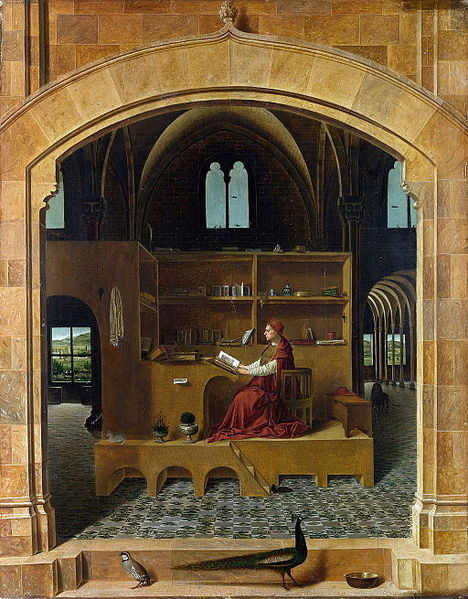

Antonello da Messina

Jerome in his study, ca. 1474-1475

National Gallery, London

Below, abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz

Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums

(Criminal History of Christianity)

St. Jerome and his ‘cattle for the slaughter of hell’

To the master Jerome, rich in wealth inherited from a noble Catholic household, we can admit without any doubt his words, ‘I have never respected the doctors of error, and I have always felt as a necessity of the heart that the enemies of the Church were also my enemies’.

And Jerome, in fact, so ardently took up the fight against the heretics that, unintentionally, supplied more than enough ammunition to the pagans, even in a treatise on virginity which he considered very precious. Still immature as in the days of his most ardent youth, the saint dedicated the text to Eustachia, a very young (seventeen-year-old) Roman of nobility, a ‘disciple’ and, in time, also saint: her celebration is commemorated on September 28. Jerome made known to her ‘the dirt and vices of all kinds’, as his modern biographer admits, the theologian Georg Grützmacher, calling it ‘disgusting’.

At the same time that he turns red-hot against the ‘heretics’ and receives, occasionally, the same qualification, Jerome plagiarises to right and left, wanting to be admired for his imposing erudition. He copied Tertullian almost verbatim, without naming him. From the great pagan sage Porphyry he took everything he knew of medicine, without recognising the merit. The ‘repellent mendacity of Jerome’ (Grützmacher) is often manifested.

Coming from such a holy mouth, it seems an exercise in moderation to just call Origen ‘blasphemous’, from whom he also ‘boldly’ copied ‘entire pages’ (Schneider), or when he says of Basilides that he was ‘an ancient master of errors, only notable by his ignorance’, and of Palladium ‘a man of low intentions’. Already in his habitual tone he calls the heretics ‘donkeys in two feet, eaters of thistles’ (of the prayers of the Jews—who according to him is a race unworthy to appear in the human race—he also said that they were heehaws); he compares Christians of other beliefs with ‘pigs’ and asserts that they are ‘cattle for the slaughter of hell’, in addition to denying them the name of Christians, since they are ‘of the devil’: ‘Omnes haeretici christiani non sunt. Si Christi non sunt, diaboli sunt’.

This most holy doctor of the Church, to whom we give special attention in this section (because we have not given him a chapter of his own, unlike the pure theologians such as Athanasius, Ambrose and Augustine), made many enemies even with people of his own party; for example the patriarch John of Jerusalem, whom Jerome persecuted and also his hermits, for many years. And even more violent was his enmity with Rufinus of Aquileia; in all these cases the discussion dealt with the works of Origen, at least apparently.

Origen himself, whose father Leonidas won in 202 the palm of martyrdom, suffered torture under Decius but refused to apostatise, and died in about 254 (he would be about seventy), it is unknown whether as a result of torture. What is certain is that Origen was one of the noblest figures in the history of Christianity.

Origen himself, whose father Leonidas won in 202 the palm of martyrdom, suffered torture under Decius but refused to apostatise, and died in about 254 (he would be about seventy), it is unknown whether as a result of torture. What is certain is that Origen was one of the noblest figures in the history of Christianity.

This disciple of Clement of Alexandria personified in his time all Eastern Christian theology. Even long after his death he would be praised by many bishops, or rather by most of the East among them Basil, Doctor of the Church, and Gregory of Nazianzus, who collaborated in an anthology of the writings of Origen under the title Philokalia. The text was even appreciated by Athanasius, who protected it and quoted it many times. Today Origen is again praised by many Catholic theologians and it is possible that the Church has repented of its condemnation for heresy, too little nuanced, that pronounced against him at the time.

In antiquity the disputes around Origen were almost constant; as is often the case, faith was hardly more than a pretext in all of them. This was especially evident around the year 300, and in the year 400, and again in the middle of the 6th century, when nine theses of Origen were condemned in 553 by an edict of Justinian, adding to this sentence all the bishops of the empire, among whom the Patriarch Menas of Constantinople and Pope Vigilius stand out. The emperor’s decision had political (ecclesial) motives: the attempt to end the theological division between Greeks and Syrians, by uniting them against a common enemy, none other than Origen.

But there were also dogmatic reasons (which, after all, are political reasons too): some ‘errors’ of Origen such as his ‘subordination’ Christology, according to which the Son is less than the Father, and the Spirit less than the Son, which certainly reflects better the beliefs of the early Christians than the later dogma. His doctrine of apocatastasis is also worth mentioning, the universal reconciliation which denied that hell was eternal: a horrible idea that for Origen cannot be reconciled with divine mercy, and finds its origin (as well as the opposite doctrine) in the New Testament.

* * *

The measure of a saint who could so rudely argue against the other fathers was demonstrated by Jerome in a short treatise, Contra Vigilantius, written according to his own confession in a single night. Vigilantius was a Gallic priest from the beginning of the 5th century, who had undertaken such a frank and passionate campaign against the repellent cult of relics and saints; against asceticism in all its forms, and against anchorites and celibacy, and received the support of a few bishops.

‘The mantle of the Earth has produced many monsters’, Jerome begins his outburst, ‘and Gaul was the only country that still lacked a monster of its own… Hence, Vigilantius appeared, or it would be better to call him Dormitantius, to fight with his impure spirit the spirit of Christ’.

‘Then he would call him ‘descendant of highway robbers and people of bad life’, ‘degenerate spirit’, ‘upset dimwit, worthy of the Hippocratic straitjacket’, ‘sleeper’, ‘tavern owner’, ‘serpent’s tongue’ and he found in him ‘devilish malice’, ‘the poison of falsehood’, ‘blasphemies’, ‘slanderous defamation’, ‘thirst for money’, ‘drunkenness comparable to that of Father Bacchus’ and accused him of ‘wallowing in the mud’ and ‘bearing the banner of the devil; not that of the Cross’. Jerome writes: ‘Vigilantius, living dog’, ‘O monster, who ought to be deported to the ends of the world!’, ‘O shame!, they say that he has bishops, even as accomplices of his crimes’ and so on, always in the same tone.

Equally harsh was the polemical tone used by Jerome against Jovinian, a monk established in Rome. Jovinian had moved away from the radical asceticism of bread and water and at that time advocated a more tolerable lifestyle; had many followers who thought that fasting and virginity were not special merits, nor virgins better than married women.

Jerome only dared to launch his two treaties against Jovinian after the latter had been condemned by two synods in the mid-nineties of the 4th century: one in Rome under the direction of Bishop Siricius, and another in Milan presided over by Ambrose, who judged Jovinian’s quite reasonable opinions in the final analysis, as ‘howls of wild beasts’ and ‘barking dogs’. On his behalf, Augustine, sniffing ‘heresy’, appealed to the intervention of the State and to better emphasize his theses he got the monk to be whipped with whips of lead tips and exiled him with his acolytes to a dalmatic island. ‘It is not cruelty to do things before God with pious intent’, Jerome wrote.

Jerome’s ‘main skill’ consisted in ‘making all his opponents appear as rogues and soulless, without exception’ (Grützmacher). This was the typical polemical style of a saint, who, for example, also insulted Lupicinus, the canon judge of general jurisdiction in his hometown of Stridon with whom he had become antagonistic, concluding the diatribe with this mockery: ‘For the ass’s mouth thistles are the best salad’. Or as when he charged against Pelagius, a man of truly ascetic customs, of great moral stature and highly educated. In spite of having once been a friend of Jerome, he describes him as a simpleton, fattened with porridge, a demon, a corpulent dog, ‘a well-primed big animal’ which does more harm with the nails than with the teeth.

That dog belongs to the famous Irish race, not far from Brittany as everyone knows, and must be terminated with a single stroke with the sword of the spirit, as with that Cerberus can of legend, to make him shut up once and for all the same as his master, Pluto.

While dispensing this treatment to a man as universally respected as Pelagius, Jerome advocates asceticism and the anchorite life: the subjects of most of his works, with so many lies and exaggerations that even Luther, in his table talk, protests: ‘I know of no doctor who is as unbearable as Jerome…’

This Jerome, who sometimes slandered without contemplation and praised others with little respect for the truth, who was for sometime advisor and secretary of Pope Damasus and then abbot in Bethlehem; a panegyrist of asceticism that enjoyed great popularity in the Middle Ages, has been raised with infallible instinct to the university patronage, in particular in the theological faculties. It seems to us that he was short of becoming pope. At the very least, he himself testifies that according to the common opinion, he was deserving of the highest ecclesiastical dignity: ‘I have been called holy, humble, eloquent’.

His intimate relations with various ladies of the high Roman aristocracy excited the envy of the clergy. In addition, the death of a young woman, attributed by the indignant people (perhaps for some reason) to the ‘detestabile genus monachorum’, made him unpresentable in Rome. That is why he fled, followed shortly by his female friends, from the city of his dreams of ambition.

In the 20th century, however, Jerome ‘still shines’ in the great Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche edited by Buchberger, bishop of Regensburg, ‘despite certain negative aspects; for his manliness of good and the elevation of his views, for the seriousness of his penances and the severity towards himself, for his sincere piety and his ardent love for the Church’.