(part 2)

Editor’s note: For the first part click here. Indented paragraphs are quotations of those commenters to whom Linder responds.

Editor’s note: For the first part click here. Indented paragraphs are quotations of those commenters to whom Linder responds.

______ 卐 ______

The Weimar Germans just came out of a nationalistic world, were proud to be German and had a 1000-year-old history. Americans have to deal with 60 years of mass egalitarian / multicult indoctrination. The first task is to build up race consciousness among Whites.

Without tv it’s a losing battle, given demographics. We’re doing what we can on the ’net, but it’s not enough and can never be. The need is to get power, then you can take care of the rest in short order. It’s like if someone is pouring water on you, you’re advising people to dry off instead of taking the hose away from the guy.

The contexts of America today and the Weimar Germany couldn’t be more different; it’s moronic to treat Mein Kampf like some sort of roadmap to American problems.

Nope, sorry Fred. It’s a power struggle, plain and simple. There’s got to be a team. It’s got to be White. It’s got to focus on the jew. Otherwise, nothing.

Posted by Lew:

Alex Linder: [Southerners] simply aren’t smart or quick enough to do battle with jews. Indeed, it is the hardest thing in the world to teach a Southerner basic facts about anything.

Hey, Deep Southerner here. I resemble that remark about dull Southerners. Keep in mind David Duke is a Southerner.

I happened to see the Duke campaign up close and worked for Duke as a low-level volunteer. White people in Louisiana turned out in droves for Duke.

In the early 1990s Jews did indeed unleash all of their power on Duke short of assassination, which might have been their next move had he won.

But it was local business interests backed by the organized Louisiana Bar and the Chamber of Commerce that were decisive in defeating Duke, not Jews and their media. A lot of Whites who didn’t give a shit about the media were told by their White bosses that if they voted for Duke, they would lose their jobs. In the end, it scared off enough people to make the difference. Duke later called that tactic economic blackmail.

Posted by Linder:

Hey, Deep Southerner here. I resemble that remark about dull Southerners. Keep in mind David Duke is a Southerner.

I generalize and overstate. Verbal caricature is a very good way to see what’s right or wrong about a proposition. I’m no footnoter. I’ll never go back and issue disclaimers—you know how to read it, you’re smart. You can read the motive. I don’t care about anybody’s feelings, including my own. We’re too womanly on that stuff. Politics aint beanbag.

Notice I don’t unload on Duke, and that is because he meets my litmus test: openly pro-White, openly anti-jew. He has truly shown the limits of the controlled electoral process, so he deserves respect.

But it was local business interests backed by the organized Louisiana Bar and the Chamber of Commerce that were decisive in defeating Duke, not Jews and their media.

You, we, must have principles to get anywhere. And the very first principle, in any pro-White organization, must be VNN’s slogan: No Jews. Just Right. They must be completely excluded. That I have to state this boggles the mind. That I have to tell MacDonald this blows the mind.

The CMS, NPI, AP3, alt-right continuum are pitch perfect for attracting disaffected people (in my opinion) away from the American mainstream and toward racial nationalism.

Not so. As I’ve pointed out, conservatism, functionally, has nothing to do with politics; that’s just the field in which it is deployed to raise money.

However, these entities appear to be tangled up with Jews at the highest levels.

Correct. They’re unprincipled, or they have the wrong principles. They will reap the predictable result.

Interesting how these liars come out of the woodwork to exculpate jews. MacDonald says that jews alone were responsible for the 1965 immigration act. Before that change, America was 90% white.

Corporations had nothing to do with opening the borders, and these woodwork liars know it. But their mission is to confuse. To make complex what real political thinkers like Hitler knew must be made simple enough that the lowest person in the crowd could understand. Politics is not about intellectuals, it’s about basic propaganda as a means to a group-desirable end.

It is all-important that average white men be taught that jews are responsible for every major social problem in the west. Of course that is a simplification. But it is essentially true and politically the sine qua non of any kind of substantial racial regenerative effort. The truth remains that jews are behind all upheaval movements in the West dating back at least to the French Revolution.

Chechar’s interpolated note: I’d need a source for the French Revolution claim.

Just as Churchill wrote as a journalist about communists back in 1919, jews were the driving power. Investigate whichever radical movement you like and you’ll find the same thing.

Only one policy cures jews and the trouble they cause: No jews. Just right.

* * *

And the maestro [Goebbels] expounds:

“The battle against indifference is the hardest battle. There may be two million people in this city who hate my guts, who persecute and slander me, but I know that I can win over some of them. We know that from experience. Some of those who persecuted us and fought most bitterly against us are today our most determined supporters. You see that the important thing for propaganda is that it reach its goal, and that it is a mistake to apply critical standards that are irrelevant.”

Does the average man know the white racial cause exists? He does not. He knows white racialism is something to beat up Republicans about.

We must make a party. And we must make a name for that party. The way to do that is clear, and I’ve laid it out in my strategy piece.

* * *

My country is called America. My ancestors came over on the Mayflower. My ancestors fought with Ethan Allen in Vermont, and George Washington to establish it. Their offspring did all they could to keep the filthy niggers you 90-IQ crackers imported to do the work you were too lazy to do yourselves, and so you could have someone around dumb enough you could plausibly look down on them.

Who are the #1 political winners of this day and age? The jews. Who are the most paranoid, obnoxious and disagreeable people on earth, hands down? The jews. But I’m sure we’ll lay them low with our big grins, friendly handshakes and genial online logrolling.

In light of jews’ success, we can conclude that paranoia, obnoxiousness and disagreeability in no way impede political success and may well be essential to it. My view is that all serious politicians must either be paranoid or synthesize the ability to think like one. Paranoia is nothing more than highly tuned, or overtuned, enemy recognition. The problem whites have as a race is they aren’t naturally paranoid. They are not naturally xenophobic by comparison with all other racial groups. They can’t even get a feel for their enemies after it is pointed out exactly what their enemies are doing. Whereas jews seem to have feelers, so in-the-blood is their hateful suspicion of all others.

In real politics, paranoia, real or acquired, is essential to success. Stalin was paranoid. Jews are a paranoid race. As I’ve said many times, shrewd people see 90% of what’s there. Paranoids see 110%. The non-paranoids in a movement can use the paranoids to pick up that last little bit they don’t catch themselves.

I can’t avoid the conclusion that most WNs [white nationalists] simply don’t believe their own bullshit, when it comes to jews.

* * *

You don’t like me or what I say when I attack Jared Taylor. Because you like him personally.

But objectively, allowing jews and apologists into our movement will render it stillborn.

How do I know it’s objective? Because the exact same thing just happened to professional conservatism in the 1960-1990 frame. Today professional conservatism celebrates commie rapist MLK [Martin Luther King] as a hero. In 1960, professional conservatism wrote about him publicly in nationally distributed publications pretty much the way we racialists do today.

You let someone like Jared Taylor into the White movement, you are guaranteeing that in twenty years, so-called White Nationalists will be saying the same things about MLK that Newt Gingrich and Glenn Beck say today.

The odd irony is that you who respect Taylor actually have less respect for him than I do. The reason for that is that you don’t understand him or the danger he presents and represents.

Ferris Bueller (something like that): “So—how do you put this into practice, apart from talking to yourself and a handful of misfits on the internet? That’s the question, and I bet you have no answer.”

Are you people on drugs? Have I not on this very thread given the basic strategy, or at least link to it? It’s not hard to do theoretically, it’s easy. It’s hard to do practically because the men to do it aren’t there. How to get them? That’s the question. It has to start with military vets at this point. And a nucleus that can data-protect itself to a level equal to the FBI-ADL. On the soft side, white curriculum, white “hilfe” stuff like Parrott talks about. I could repeat what I’ve said hundreds of times, but you’re not really listening anyway, or you’d know my basic strategy.

Haller: Why not use your talents in a more persuasive way than spending a decade of hurling abuse around the internet? I don’t know how you support yourself, but you obviously have free time. Why not use that free time to gain some real, objective academic expertise in the field of Jewish Studies? Even if you didn’t wish to return to grad school, as I’ve now done with Catholic Theology (and that PC world probably would not accept you), why not subject yourself to a disciplined course of study in Jewish political involvements (as Kmac did), and then write a book on your political strategy re dealing with Jewry and allied issues?

An academic understanding of jews and a political movement to oppose them have nothing to do with each other. Anyone new to the idea that jews are a collective bad rather than good can verify the claim in no more than a night or two of reading. Knowing more than that about jews is nice but not necessary—from the strategic political standpoint. It is the work of the enemy to make it seem as though our cause is more complex than White-good / jew-bad. It’s not.

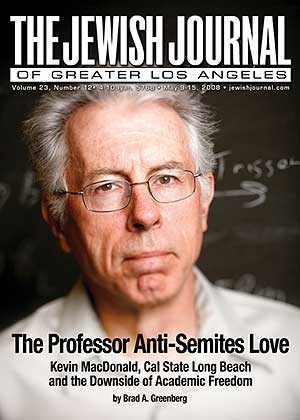

And advanced academic degrees are no proof against political unwisdom. Look how unthinkingly MacDonald participates in and validates by his presence the Charles Martel Society, which admits… jew-apologists. MacDonald by his actions confuses followers about whether jews are the problem or part of the solution. He confuses us with them in the eyes of onlookers, thereby vitiating a racial cause. “Each man kills the thing he loves,” wrote Wilde.

This world is set up so that it is as easy to produce the opposite of our intention as what we intended. Extremely careful attention must be paid.

Leon, I don’t think you’re capable of grasping certain things. It’s imagination and emotion that move the world, not footnotes and studies. You think that an academic has more credibility than an effective wit. It is not so. It is the opposite. Sometimes the two are united in one man, as in Goebbels; more frequently they are separated. Hitler achieved his deeper-than-MacDonald understanding of judaism not in college libraries but on the streets of Vienna.

The way to a man’s heart is through his marrow, not his mind.

If the book were sober, factual and free of invective,

it would be boring as all fuck and mere repetition of what 100 more academically inclined writers have said before.

Don’t you see, Haller? You’d have me throw away my real skills to become a third-rate repeater—repeater of a message better men have already laid before us a dozen times. “Sober, factual and free of invective” are the opposite of what produces political change.

You really are almost a caricature of the bourgeois mind. I almost would suspect you of satire but not quite.

Leon—have you never read George Lincoln Rockwell? He has your type nailed. Go read on him on his political progress through conservatism. Absolutely nails what’s going on. He skewers your POV [point of view] and the type that holds it. Again, it’s the MacDonald mindset too. That we are going to outrespectable the yid-led left to victory. Outmanners them. Outnice them. This view is not merely crazy, it is probably unique in world history: that an oppressed minority that accurately perceived its opponent as mendacious-aggressive nevertheless believed it could triumph over that vile criminal set with nothing more than facts and reason.

As Rockwell said, the delusion that the masses can be moved by facts and reason is the eternal stumbling block of the right. You, in telling me to become a shitty academic, would have me throw away precisely what it is that I have that potentially could cause the jews serious problems—invective, verhetzing as they call it in deutsch. I know how to get in people’s marrow, and that’s knowledge you can’t learn in any school. Go back to school? Other than weedeat mosquito-filled swales, there is nothing I would less rather do than go back to where the snakey-snidelys snit and snoot at the non-semitophilic.

Doing what you’ve been doing seems like a waste, merely talking to other talkers.

It does not seem so to me.

I think progress has been made in the last decade. More men understand the jewish root of our problem; more sites expound on it. I’m happy to continue widening the circle.

Alex, Jared Taylor has been doing his thing for over 20 years—and nobody’s burning incense for MLK. It didn’t happen.

Of course it hasn’t happened—yet. It’s a long play by the jews. They have pre-infiltrated WN so that if WN takes off (and jews know it well could, because they know what they are doing to our race, and how a section of that race must inevitably respond), then they have long in place extremely skillful, appealing men to mislead the angry mobs, and channel their anger in a non-jew-hostile direction. This is the purpose Jared Taylor exists to serve. William F. Buckley served it before him, and Taylor has said he wants to be the WFB of white nationalism.

It’s not what WN is today that worries the jew—all the reports put out seemingly monthly are pure bullshit—it’s what it could be if it ever takes off.

Alex, none of these people would find you tolerable in the least. You think P.J. O’Rourke, who was married to Lena Horne’s granddaughter, would want to have lunch with you?

Funny for a number of reasons.

1) such a womanly way of thinking: ooh, mrs dallypimple wont have snickers with me at forenoon.

Honest to god, get off the net and go buy maxipads, girlie. I care about effects and how they’re produced, not whether these people would go to McDonald’s with me.

2) How the hell do you possibly know how dead people in different nations would react? What’d you convene a quickie séance and poll them? I love how people just grant themselves all-knowledge of things no one could know.

Why do so few of you study the Civil Rights Movement’s history, and learn from its methods?

Because they only work if you control the mass media.

The suggestion of this false model usually signals the voicer is an anti.

The whole notion of duplicating the black-privilege movement is so ridiculous on the face of it that I assume the person advocating such is either a blockhead or an anti.

Claims that we can and should copy the ’60s jew-organized niggers, regardless of the intent of the advocate, play into the jewish lie that it was the “morality” of the anti-White movement that won whites over rather than raw jewish legal and media power.

Good example is Knoxville. The media treated us Whites sticking up for Christian and Newsom as hostile outsiders bent on stirring up trouble. Trolls on here repeat that lie. But when the jew-fired radicals went down to the southern region in the sixties, they were treated as jesus figures come to the benighted land to spread love and justice. The locals were the haters.

What’s the common denominator? Anyone sticking up for whites is the bad guy, and anyone pushing the jew agenda is the good guy.

The “civil-rights” strategy can’t work unless your side has the courts protecting it and the mass media marketing for it. Only simpletons and antis masquerading as WN can’t understand this. The more I read Haller, the more his denseness seems deliberate.

Haller: Heretical as this will sound to Linder, I’m not convinced that Jews can’t be brought to a new, more constructive relationship with Aryans.

How do you propose to bring them, lacking any power? They’ll laugh at you. They don’t care about reason or morals, only power. And you don’t have any. That’s why all this talk of secession or separatism or forming Republics is ridiculous. Rather than empty, foolish talk about secession, Republics, separatism and the like, we must worry about much more basic things: a) defining who we mean by “we”; b) defining who we mean by the enemy, them; c) forming a national political vehicle; d) choosing a strategy to acquire power; e) employing the strategy and actually acquiring that power. Then and only then can we force the jews to deal with us, or die resisting.

The people are already with us. What does that mean? It means if “we” that great undefined are anywhere near equal in power in relation to ZOG’s official parties, or even merely appear to be heading toward it, the people will side with us because we represent what their actual behavior shows they already appear: closed borders, free association, execution of nigger criminals, gun right, end to foreign wars/aid.

Our strategy cannot be based on appealing to people or teaching them because we don’t control the high points. It’s like a guy with a single used car trying to outsell some massive car lot. We have to assume the people are with us based on their deepest behavior—where they move, who they marry. And assume they are not heroes, and will not take serious risks short of emergency conditions (massive social breakdown), but will follow the forces of white normalcy we represent if the social costs of that following are anywhere near equal.

Linder’s model—an anti-localist national approach…

My approach is not anti-local at all; local is quite important. My strategy correctly recognizes that the power suppressing our racial interests emanates from D.C., not from some hamlet in rural Wyoming, Arkansas or South Carolina. It’s like some of you aren’t capable of reading the papers. We must persuade people! We must do things in Our Town and never lift our heads! And what happens? You do anything serious, the feds coming marching in with the civil rights tyrants and jail you, sue you, or abuse you in the press. You can’t even run classified ads discussion who you want to rent a room to, because that’s a federal civil rights violation. There’s no way to change that locally, it’s a national issue. There has to be a competing, oppositional national body facing up to the jews in order to take that power back from them. Local stuff is important for other reasons, only secondarily for political reasons. Most white-majority areas don’t have any serious political problem, and if they do, say black crime or illegal-alien-caused problems, it’s precisely because the feds won’t let them deal with them. Who sues the small town in Pennsylvania that passes some tiny measure to discourage illegal aliens? The Justice Department. Not out of Feral Hogg, Ala., but out of Washington, D.C. Again, I can’t help but see deliberate denseness here on the part of these anonymous mouthers.

We need power. Power means national power. There’s no such thing as state and local power in the USA in 2011. Not when a federal judge can simply toss out the legitimate vote of a large democratic majority. And the media always side with the judge.

The only portion of KMD’s A3P discussion that was a big disappointment to me was this: he mentioned an internal debate about whether the A3P should be an explicitly or implicitly White vehicle.

Imagine Hitler and the National Socialists internally debating whether they should be explicitly pro-Germany or implicitly? A kosher-salted garden slug would be a good symbol for A3P.

If this is true and there is actually disagreement within the A3P on this basic question, it does not seem likely the national A3P plans to do what I have been hoping for — making confrontation Jews in a rational, founded and reasonable way using KMD’s own research and findings part of their activism.

There’s nothing wrong with rational criticism of jews, but it belongs underneath the gaudy flowers of vicious emotional attacks for the harm they’ve done our race. That KMD et al. don’t get this is why they aren’t worth following. Emotion is where the winning lies, not in reason. In the heart, not the head.

It is an infallible mark of the fool or the liar that the jewish “thing” can’t be understood by normal people without years of training, prayers and handholding. Garbage. Any person of normal intelligence and most people of subnormal intelligence can be taught the jew thing in a couple of minutes.

The correct strategy is to attack the conservatives as cowards and weaklings, which they are. Take on their standard-bearer directly, the worst of them all: Pat Buchanan.

Chechar’s interpolated note: A recent TOO article deals with Buchanan’s most “valiant” book (here), which will be published next month. According to the reviewer, Buchanan doesn’t mention the Jewish Question.

* * *

Somehow the jews took power without ever troubling themselves in the slightest with Flyover. Hmm… now how did they do that? Oh. They bought up the mass media, they paid off the politicians, and they took over the law schools. But we’ll get ‘em back by…running candidates in local dogcatcher elections. Yeah, thatz the ticket!

Wandrin: “Jewish media and legal power specifically played on White concepts of universal morality. It didn’t work on everybody, especially not those with a lot of personal experience of living among blacks, but it worked on enough White people to tip the balance. Films like To Kill A Mockingbird and all the others like it were enough on their own to start the multicult in places like Sweden.”

Yeah, but that’s a deeper problem—christ-insanity. And still you’re evading and failing to counter my point. Morality is not some independent abstract thing that is undeniable, in many instances, if not all, it’s a matter of interpretation.

Are they civil rights workers? Or jew-led, jew-instigated anti-White troublemakers pursuing a genocidal agenda?

You see how easy that is? It is purely a function of who controls the media, who gets to define who is who. They simply map on their political concerns to existing mores and, yes, as you say, they fit them to christian morality. Child’s play to cunning kikes.

We can’t simply copy what the jew-led nigs did because our cause will not be played the same way in the media. We will be played as the bad guys. The evil outside shit-stirrers. I’m not theorizing, the framers interviewing people in Knoxville were taking great pains to ask about where everybody was from so they could make precisely that point: “outsiders bringing trouble.”

Media control is damn near everything. What part of that is too hard to figure out?

You can’t reverse engineer it without controlling the institutions. To succeed at cultural marxism requires a verbal ability our side doesn’t possess. Look at how many of us use the enemies’ terms unthinkingly. MacDonald uses “racism” and “Holocaust” and “anti-semitism” like they’re meaningful words representing perfectly valid concepts, rather than attacks on the cause he thinks he is defending. If our smartest guys are clueless, are the dumber ones any better?

Look… a hostile minority took over this country. It did not do it by voting. It did it by legally and sometimes illegally acquiring the mass media, and simultaneously taking over the money. It uses its immense and growing power to create a false reality, a false consensus reality, as has been well said. No “hey kids, let’s put on a show” counter effort is going to defeat that. A lot of you don’t seem to grasp that. The only possible thing that can defeat that is extremely organized, life-and-death loyal opposition. And 90% of you don’t even agree on the necessity of keeping to a political. Some of you, pretending to be us, actually brag about being stupid, indoctrinaire, contradictory. Let me tell, my pudgy little friends. The jewish cunt will not fucked with that tiny pecker.

* * *

By all means, people are free to waste another 100 years speaking in their indoor voice, raising their niggling finger, and prefacing everything they say with disclaimers. But if you want change, you have to create a national angry groundswell willing to slur and kill and sup on the blood of its enemies, and you don’t get there by appealing to selfish bourgeois cowards.

Anger is good for our cause. Reason is merely necessary.

Teaching people about jews in the bloodless, carefully emotionally controlled academic prose is fine for a book, but not for practical politics. To make CofC’s lessons real, vibrant, meaningful and effective requires someone doing more or less exactly what I said. Only emotion will get us where we need to go. Reason shows the way and the how, but emotion is the means.

Wandrin: “The essence of cultural marxism is simply relentless attack on every critical aspect of the dominant culture until it collapses from exhaustion at which point you can replace it with something else.”

Yeah, but you can’t do that without controlling the high points: the pulpit, the press, the law schools, the academies. Especially not if what you’re preaching is hugely and ridiculously anti-majority.

They required great verbal ability because they were selling poison. We don’t need as much because the multicult is one big genocidal double standard and we’re selling the cure.

Yes, that’s true, to an extent. But still the basic problem remains: unless you own the mass media, you’re shouting in the wind. And the jews operating our power institutions are not going to allow themselves to be displaced or infiltrated. Their control mechanism is extremely strong, and their threat-paranoia is impeccable. I really believe that it’s late enough in the day that only a counterforce that begins with soldiers has any serious chance. Or we can’t wait until ZOG collapses of its own internal contradictions, as a marxist would say. But I actually believe if we had even a few hundred, say, veterans, and they stuck to a defined political line and pursued a solid strategy they could become a national force in short order.

Remember the mantra: smart people always undersimplify. Let’s not make that mistake.

Our people need know only that jews are bad and Whites are good. Everything the majority of our people hates we peg to the jews, and quite justifiably so. Everything they love we tie to the existence of a racial-oriented state.

Simple, simple, simple. Emotional, emotional, emotional. Repetitive, repetitive, repetitive.

We don’t control the mass media. That is the most important political fact we face. Like birds in a north wind or salmon headed to spawn, we must face that north wind, that cascading water, directly. Directly is the only way to cut or knife through it and get where we need to go. Three quarters wont do it: 3/4 gets blown over bowled over, sucked under.

Just say no to cleverness!

Attacking the double standards and moral inconsistencies of the multicult will reduce its power over the audience you’re addressing.

No. It will not. The leftists already know about the double standards and don’t care. They like seeing white males punished, and love o hear them whining about it.

If complaining about double standards and unfairness did something we wouldn’t be in this mess because that’s all conservatives have ever done. It never has worked and never will work. We’re not in a debate. We’re in a monopoly harangue where we have no loudspeaker and our opponent has 1000. The question is how do you do something about it. For that the conservative has no answer. He just keeps appealing to the very power that created the unfairness in the first place. How crazy is that? Like the judeo-left doesn’t know what it’s doing, intend it, and enjoy it? You have to be insane to be a conservative. It’s simply a way to avoid fighting. It’s a euphemism of a political position: we just mass-aggree to operate on the delusion that our enemies are rational and fair-minded folk, even tho a child of 2 could see they’re wicked liars. We don’t need more conservatism, we need a party for serious adults.

Posted by Trainspotter:

Linder: “They don’t care about reason or morals, only power. And you don’t have any. That’s why all this talk of secession or separatism or forming Republics is ridiculous.”

Any more ridiculous than speaking of world conquest during an era in which we are not allowed so much as a racially exclusive donut shop?

We’ve now got well over 100 million non-whites in this country. We have an enemy entrenched in all the high points of cultural and political power. The Jews were able to simply buy up these levers of power, or pursue the long march through the institutions. We are allowed neither of these options; the doors are closed. There will be no long march for us.

So we can’t replicate what the Jews did. We also can’t replicate what the NS did in the twenties and thirties. For all the talk of Weimar decadence and Cabaret style indulgence, Germany was still a fundamentally sound society, at least in the sense that it was 98 to 99 percent white and the broader culture leagues above what we currently endure. They faced a small and rotten alien elite combined with a relative handful of German lickspittles. Smash that small and alien elite (we’re talking a total population of just a few hundred thousand), and you pretty much had a healthy nation again.

That’s a long way from where we find ourselves today.

While we can take lessons from successful movements of the past (both pro and anti-white), we in many respects are in uncharted waters. We’ve got to figure it out ourselves, because no one has or will do it for us.

At the end of the day, I think most serious thinkers agree that there is no peaceful way out of this situation, at least on this continent. That is mere foretelling, not advocacy.

Given that situation, the question then becomes how exactly do you motivate enough people to take enough action to gain…enough? Who the hell is signing up for world conquest when we can’t even control a truck stop? At this point, who is signing up even for removing 100 million non-whites from the North American continent? Who is signing up for the polarization strategy, when the end game is… what exactly?

We’ve got to come up with something that is at least remotely viable. The idea of the White Republic is an attempt in that direction. If we can turn this into an idea that has legs, that gets some traction, you’ll soon enough get all the polarization that you like.

We can critique, deconstruct, and mock our opponents (however they are defined), but unless there is an end result that a lot of people can sign off on and get passionate about, it’s just not going anywhere.

And while it falls somewhat short of “world conquest,” a decisive result on the North American continent would be of immense benefit to our kindred peoples in Europe and across the globe. Some form of secession may well be the answer, and at least has the potential to serve as a galvanizing point. Most people won’t fight, or even take risks, over mere vagaries or seemingly impossible scenarios (religious nuts being an arguable exception here). But if you’ve got something that they can wrap their minds around, then you’re either fer it or agin’ it. That’s your polarization right there, all the polarization that you’ll ever need. It will be obvious, and it will matter.

In other words, and for all its faults, our movement has done a pretty damn good job in terms of critique, but it has done very little to offer a tangible way out of our predicament that seems even remotely viable. When people see no way out, can they be blamed for simply keeping their heads low and muddling along as best they can? Going along to get along? Can they be blamed for enjoying Buchanan who, giving credit where it is due, is both a good and informative writer? What’s the harm when there is no solution anyway? “Hey, I don’t know where this is going. Maybe Buchanan does!”

You speak of polarization, but my argument is that will take care of itself when we solve a more fundamental problem: how to galvanize. There is plenty of physical courage left in our people. Huge numbers are willing to risk life and limb for their country. Hell, the empire can still get an awful lot of people to go off and die in third world shitholes. Our challenge is to develop and spread a vision that people will actually be willing to fight for. We haven’t done that, and until we do, polarization isn’t going but so far.

When nothing is worth fighting for, we can either be sewing circle faggots and engage in silly internet drama on the one hand, or we can be gentlemen and agree to disagree on the other hand… but so what? To what end? Until we have a meaningful focal point that really has some traction, it doesn’t matter much one way or the other, at least in the minds of most.

Posted by Linder:

Trainspotter: “You speak of polarization, but my argument is that will take care of itself when we solve a more fundamental problem: how to galvanize.”

Polarization is a political strategy… for a group with a purpose. We have to start by organizing in our own name—on a racial basis. That’s what we don’t have now. For crissake, even MacDonald’s vehicle can’t decide whether it’s openly white or not. The political point any sane White party would recognize is whites have no interest in political association with jews or the muds… Therefore they organize on the basis of race. Not region. Not religion.

Greg Johnson: “My main problem with you is that you make shit up. You pass off hypotheses and likely stories as truth, e.g., your claims about the motives of people you do not like, i.e., that certain people are sellouts for money and social status, that Jared Taylor is running a false opposition for the Jews.”

Whether AmRen was set up that way, became that way at a point, or has been entirely under Taylor’s control the whole time, it has in fact served in exactly the same capacity as John Birch Society, a front group known to false opposition formally controlled by the jews paying Welch’s salary (claimed by Revilo Oliver). AmRen encourages harsh criticism of muslims and blacks, but forbids any criticism of jews and Israel. That is, Taylor is deliberately encouraging whites to blame themselves.

And when I claim that no, that is not what Taylor is up to, you falsely claim that I am motivated by personal considerations rather than impersonal principles. For you, “impersonal principle” seems to mean, in part, making judgments about persons without any actual knowledge of them, which just boils down to you brazenly passing off speculation as facts up and waving away inconvenient criticism as sloppy and unprincipled.

Apparently my point is too subtle for your to grasp. I don’t need to know anything about Taylor other than the positions he takes. His positions are illogical and contradictory. For example, he says jews are whites. And whites should blame themselves. But you [can’t] blame jewish whites at AmRen. He further says he doesn’t take position on the jewish question, but much of his editorial space is taking up with muslim-bashing. Yet, as I said, he will not allow any criticism of jews. When it comes to race, he’s against open border, but he’s also against printing the fact that jews alone drove the 1965 immigration act that opened them. When it comes to solutions, he demands the restoring of free association, but never mentions it was organized jewry that destroyed that civil right in the name of civil rights.

Boy, he’s a bait can full of slippery contradictions to anyone with a working mind. Greg Johnson’s mind usually works pretty well. It goes on tilt when it comes to Taylor. What could account for that? It is reasonable to suspect that personal affection accounts for it. Particularly when in this very bit Johnson says I can’t judge Taylor because I don’t him personally. But you don’t need to know someone personally to judge them when you have their contradictory words in front of you, alongside their proven record over time.

At present, our movement is confined to the internet and our only real strength is our credibility, which we have to preserve carefully, especially since we are already so heavily handicapped by trolls, whether calculating or merely psychotic, and webmasters who give them free reign.

I agree. That’s why intelligent men should not let a fraud try to get away with claiming he separates the jewish question from the nigger question, which is as ridiculous as separating the dancing monkey with the cup from the organ grinder.

Okay, but more to Trainspotter’s central plaint, How to galvanize the White masses? Take over tv and broadcast non-stop “Knoxville Burnings.”

According to your tastes…

It isn’t my tastes but my perception of fact. I could be wrong, but it’s certainly not my tastes. If my tastes had anything to do with it, the masses would be attracted by witty vicious essays, and stimulated by them to go out and make the world anew. Turns out it doesn’t work like that—with the masses. You need tv. I didn’t say video, either. A video on youtube with a million views is still not tv. You need tv.

the clear answer would seem to be an ideology to galvanize the White few who would do the work of galvanizing the White many with muckraking.

If you don’t have tv, and we don’t, nor have we any prospects in near-medium future, then best you can do is come up with strategy and sell it to winter patriots. Make the difficulty of the cause the appeal, if appeal you must have. That’s how you attract the few and the strong. Once you have those, and I think a few hundreds would be enough to get it started, as long as you had a good number of vets in there, I think it would snowball, even without tv. I think if this group were following the strategy I indicate—a very simple and clear one—you could quickly attain national prominence as the one group that actually means it, apart from the jews.

How long do you think it would take to become a thing? Men who actually organize around (white) race—the thing that scares the establishment the most—and who wont back down when called racialists? I suggest to you that the minute words gets round that one of those is back in town, then it just might take off. And if that happens, you begin to get the point where that sitting judge is, let’s say, less likely to obstruct the will of the democratic majority for simple animal fear of his own ass.

Mob: “It stemmed from his deep-rooted Catholicism, which apparently teaches that Jews can and should be converted to Catholicism. In this, he resembles both Buchanan and Sobran.”

Yes. It’s the special horror of Catholicism. It simply defines the jew problem (the race problem) out of existence. But that doesn’t mean the problem goes away. It just means the catholic can’t acknowledge it. It also means that the catholic is the practical as well as theoretical enemy of the man who isn’t afraid to acknowledge it. The racist is “immoral” according to the Pape and his disskirted lessers.

As Philip Dick said, reality is that which doesn’t go away when you stop believing in it. By that standard race is real and jesus isn’t. Catholicism is fundamentally and unavoidably anti-White because it denies reality.

* * *

Of course, the posers at alt-right [Alternative Right] have no problem working with jew Gottfried. If you’re neither fish nor fowl you’re foe.

Yeah, another example of the one-way street that is the pale right’s dealings with jews. They subsidize, flatter and fawn over their controllers, namely jew Gottfried; in return they are enjoined to observe the same taboos the neo-jews insist on. The ICs [implicit conservatives] have much intellectual understanding, no political understanding, and a positively feminine concern with how they look to others.

[In the] NPI, which is a good proxy for CMS, you have it loaded with jew apologists like Taylor and outright jews—Stix and Rubenstein. So if there are technically no jews in CMS, which I do not assert, it remains true that there are certainly multiple people in CMS who are jew apologists and, in the case of The Turd, jew employers.

Posted by Mob

It’s distressing that the subject of Jared Taylor is still or again being discussed.

Back in January of 1999, when many of us were on both the original (not the present) AmRen elist and the CofCC elist, a huge problem arose when it was suggested by one of the contributors that David Duke, campaigning for Congress, should run for President in 2000 on a Buchanan/Duke ticket. I remember suggesting it be a Duke/Buchanan ticket instead.

Two sides rapidly developed, pro-Duke and anti-Duke. Some of the antis were Jewish, but some, like John Killian (dispensationalist Christian) were not. The thrust, though, was that there are “valuable Jewish members” of CofCC and AmRen—more valuable than Duke, who they would not want to associate with, and who would turn outsiders against the groups.

The outcome was that both of the heretofore very active and quite high quality lists were closed down, the same day, supposedly because of high traffic, but really because of the Duke affair. This was 1999, seven years before the Duke-Hart episode at the 2006 AmRen meeting, after which JT [Jared Taylor] sent out his formal letter, which I think I mentioned earlier in this thread or the Elitism thread.

Posted by Linder:

Jews are brought into the organization. This has only one meaning: American Renaissance is a jewish operation.

It should be treated that way. But it’s not. And those who say it should be are transformed into the bad guys by the WN who think principles don’t matter. It makes our cause a joke to say the things we do about jews—then turn around and give a loving embrace to someone like Jared Taylor who welcomes them into his fold.

Posted by Jimmy Marr:

Greg Johnson on Jared Taylor: “he also might believe that it is important to separate the race issue from the Jew issue”

I suppose it’s possible that Jared Taylor could actually believe such a thing, and I suppose Greg Johnson might actually believe that its harmless to believe such a thing.

But I believe no such thing, and I believe that believing such a thing is murderous (pre-meditated or involuntary).

My belief is supported by James Bowery’s theory of Jewish virulence.

A theory of Jewish virulence put forth by James Bowery is that it evolves from horizontal transmission of Jews between nations, in the form of repeated migration, since at least Babylonian times. Moreover, since diaspora Jews have become dependent on virulence for survival. They promote immigration and naturalization laws that are friendly to horizontal transmission more generally (here), resulting in virulence evolving in other populations.

This makes Jewish virulence more analogous to immuno-suppression virulence, such as HIV creates. This theory of Jewish virulence is complementary to both Kevin MacDonald’s thesis documented in The Culture of Critique and to Richard Faussette’s Niche Theory.

Under Bowery’s hypothesis, Jewish virulence evolved from the following horizontal transmission cycle (see Faussette’s Niche Theory for a possible starting point):

1. Hyper centralization of net assets (communist, capitalist, monarchy—doesn’t matter)

2. Social breakdown as middle class (Yeomen) are unable to afford subsistence

3. Grab and convert wealth in easily transported forms (gold historically, diamonds more recently, etc.)

4. “Virulent antisemitism” breaks out

5. Emigrate leaving behind less “savvy” Jews to take the heat

6. Cry out for help to elites at destination nation while offering concentrated wealth to enter new cycle (see step 1).

Posted by Lew:

It would be one thing for Jared Taylor to distance himself from the unhinged Jew obsessives, the simple-minded Single Jewish Causers and the irrational Jew haters on the White right.

Unfortunately, Taylor does not do this. He distances himself from those who fit that description and those on the White Right who are simply responding to ongoing Jewish aggression against White people.

Based on his public actions, Taylor recognizes no meaningful distinction between the former and the latter.

Taylor’s stance can be accurately summarized as follows:

“If you regard Jewish influence as one problem among the many problems that White people are facing in this world, fine; you are welcome to work with me as long as you check your concerns about Jewish subversion at the door.”

It’s not as if Taylor has an audience of millions like Pat Buchanan. It makes perfect sense for Pat Buchanan to cut things off at a certain point in order to keep his visibility in the mainstream and send books with vital information to the top of the best sellers list.

But Taylor has no visibility to preserve, his books will never appear on that list, yet he embraces Jews anyway and does so despite the fact that Jewish influence is the main reason he is a marginal figure.

Posted by Jimmy Marr:

Haller: “Alex Linder writes with a shotgun. Some of the pellets are made of steel; some lead; some cookie dough; and some shit.”

If the above is any indication, Alex’s writing is also having a salutary effect on your prose, Leon. Nice work.

Thanks for the kudos upthread. I deserve no share of credit for Bowery’s Razor. It reflects a level of creative insight of which I am wholly incapable if left to my own means.

Lew: “The people who bear the burden of explanation are the Jew-wise nationalists who work with philo-semites like Taylor and / or who also work with Jews.”

Yes. If we apply Occam’s Razor to this equation, the burden of proof falls squarely on the shoulders of those attempting to justify a more complicated explanation than Bowery produces in 50 words.

When the jews were coming here in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, why didn’t alarm bells ring?

Was the history of the expulsions suppressed? Would Americans have allowed entrance had they full knowledge of jew chicanery?

I don’t know, but if we assume I’m correct in my assertion that the Jewnome is host-specific to Europeans, it brings up another question: Why are they trying to blend us into other races?

The next question: how to break this cycle.

Alex’s proposal, unless fully executed, will ultimately serve to perpetuate the cycle. James Bowery mentions “blocking metabolic pathways” in the later part of his interview with Jim Giles.

It seems to me that whether we treat the Jewish problem with Zyclon B or through legislation designed to disable the inexorable logistics of their vampiric porosis, all will be equally and rightfully genocidal in their eyes, because they cannot survive without a racial host and they are host specific to Europeans.

So, regardless of proposed solution, Jews can be rightfully expected to sabotage the process at every opportunity, and must therefore be barred from any participation in the project.

NO JEWS. JUST RIGHT.

Posted by Hunter Wallace:

As I have described above to the best of my ability, the doctrine of the Single Jewish Cause is false, and so is the doctrine that “all White people are on the same side.” Both of these old WN chestnuts are easily refuted by history.

The truth about the Jews is that Jews are a contributing factor in our racial decline. It is one factor among many other factors—the salience of the Jewish Question also varies across countries—with Jews having the greatest impact in the United States, Britain, and France after the Second World War.

In the American North, there is a mythology that has grown up among WNs that “Jews made us liberal.” Every Southern historian howls with protest: what about John Brown, William Lloyd Garrison, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner and the rest of the Black Republicans and the Wide Awakes who were behind Reconstruction?

As a matter of fact, it was the North that invented Jim Crow in the Antebellum era. The North had black codes that fined or outlawed black settlement in states like Illinois, Oregon, and Ohio. They also [had] anti-miscegenation laws in most of the Northern states.

Well, in the aftermath of the War Between the States, the North repealed the black codes, repealed the anti-miscegenation laws, and banned segregation in hundreds of state statutes in the Northern states… by the year 1900.

That’s a historical fact. Look it up.

___________________

Chechar’s note:

I’m not sure if Linder believes in a single cause of Western malaise since he himself blames “Christ-insanity” as a contributing factor. What is clear to me is that without the French revolutionaries’ blunder of granting full rights to the Jews, Europe would have been eventually spared from Bolshevik genocides and the Gulag (see here). And America would have been spared from the pressure Jewish groups that opened the gates for massive, non-Aryan immigration into the US—among many other calamities wrought by the tribe.

For those unfamiliar with MacDonald’s trilogy I’d recommend this Preface. For those already familiar with the JQ, James Bowery’s theory of Jewish virulence—Jim Giles’ interview of Bowery already linked above—is worth listening (Bowery proposes a solution to the Jewish problem different from Linder’s exterminationist standpoint).