by Evropa Soberana

The destruction of the Greco-Roman World – 2

(Fourth century – Cont.)

372

Emperor Valentinian orders the governor of Asia Minor to exterminate all the Hellenes (meaning as such the non-Christian Greeks of ancient Hellenic lineage, i.e., the Aryans; and especially the old Macedonian ruling caste) and destroy all documents relating to their wisdom. In addition, the following year he again prohibits all methods of divination.

It is around this time when Christians coined the contemptuous term ‘pagan’ to designate the Gentiles, that is, all who are neither Jews nor Christians. ‘Pagan’ is a word that comes from the Latin pagani, which means villager. In the dirty, corrupt, decadent, cosmopolitan and mongrelised cities of the now decadent Roman empire, the population is essentially Christian but in the countryside, the peasants, who keep their heritage and tradition pure, are ‘pagans’. It is in the countryside, oblivious to multiculturalism, where the ancestral memory is preserved. (Both Christians and communists did their best to end the way of life of the landowner, the farmer and the peasant.)

However, this peasant ‘paganism’, stripped of priestly leadership and temples and finally plunged into persecution and miscegenation, is doomed to eventually become a bundle of popular superstitions mixed with pre-Indo-European roots, although something of the traditional background will always remain, as in the local ‘healers’ and ‘witches’ who for so long subsisted despite the persecutions.

Ending classical culture was not so easy. It was not easy to find all the temples or destroy them. Nor was it easy to identify all the priests of the old religion, or those who practiced their rites in secret. That was a long-term task for a zealous, meticulous and fanatical elite of ‘commissaries’ that would last for many, many generations: centuries and centuries of spiritual terror and intense persecution.

375

The temple of the god Asclepius in Epidaurus, Greece is forcibly closed.

378

The Romans are defeated by the Gothic army in the battle of Hadrianopolis. The emperor intervenes and, through a sagacious diplomacy, makes allies (foederati) of the Goths, a Germanic people originally from Sweden: famous for their beauty, and who had a kingdom in what is now Ukraine. Some time later, in 408, after the fall of Stilicho (a general of Vandal origin who served Rome faithfully but who was betrayed by a Christian and an envious political mob), the women and children of these Germans foederati will be massacred by the Romans, propitiating that the men, prisoners of the rage, join en masse the German commander Alaric.

380

Emperor Theodosius I (Theodosius the Great for Christianity) decrees, through the edict of Thessalonica, that Christianity is officially the only tolerable religion in the Roman Empire, although this has been obvious for years. Theodosius calls non-Christians ‘crazy’ as well as ‘disgusting, heretics, stupid and blind’.

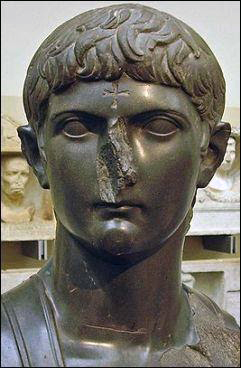

Emperor Theodosius I

Bishop Ambrose of Milan starts a campaign to demolish the temples in his area. In Eleusis, ancient Greek sanctuary, Christian priests throw a hungry crowd, ignorant and fanatical against the temple of the goddess Demeter. The priests are almost lynched by the mob. Nestorius, a venerable old man of 95 years, announces the end of the mysteries of Eleusis and foresees the submergence of men in darkness for centuries.

381

Simple visits to the Hellenic temples are forbidden, and the destruction of temples and library fires throughout the eastern half of the empire continues. The sciences, technology, literature, history and religion of the classical world are thus burned. In Constantinople, the temple of the goddess Aphrodite is turned into a brothel, and the temples of the god Helios and the goddess Artemis are converted into stables! Theodosius persecutes and closes the mysteries of Delphi, the most important of Greece, which had so much influence on the history of ancient Greece.

382

The Jewish formula Hellelu-Yahweh or Hallelujah (‘Glory to Yahweh’) is instituted in Christian Masses.

384

The emperor orders the praetor prefect Maternus Cynegius, uncle of the emperor and one of the most powerful men of the empire, to cooperate with the local bishops in the destruction of temples in Macedonia and Asia Minor—something that Cynegius, a Christian fundamentalist, does it happily.

385-388

Maternus Cynegius, encouraged by his fanatical wife, and together with Bishop St Marcellus, organises bands of Christian ‘paramilitary’ murderers who travel throughout the Eastern Empire to preach the ‘good news’; that is, to destroy temples, altars and reliquaries.

They destroy, among many others, the temple of Edessa, the Kabeirion of Imbros, the temple of Zeus in Apamea, the temple of Apollo in Didyma and all the temples of Palmyra. Thousands are arrested and sent to the dungeons of Scythopolis, where they are imprisoned, tortured and killed in subhuman conditions. And in case any lover of antiquities or art comes up with restoring, preserving or conserving the remains of the looted, destroyed or closed temples, in 386 the emperor specifically prohibits the practise!

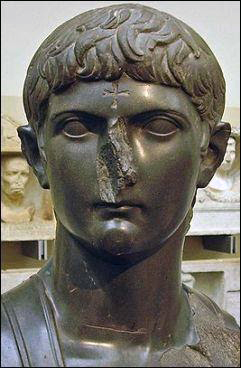

Bust of Germanicus defaced by Christians,

who also engraved a cross on his forehead.

388

The emperor, in a Soviet-like measure, forbids talks on religious subjects probably because Christianity cannot be sustained and can even suffer serious losses through religious debates. Libanius, the old orator of Constantinople once accused of magician, directs to the emperor a desperate and humble epistle Pro Templis (‘In Favour of the Temples’), trying to preserve the few remaining temples. The emperor did not pay attention to him.

389-390

All non-Christian holidays are banned. The antifa of those times, headed by hermits of the desert, invade the Roman cities of East and North Africa. In Egypt, Asia Minor and Syria, these hordes sweep away temples, statues, altars and libraries: killing anyone who crosses their path. Theodosius I orders the devastation of the sanctuary of Delphi, centre of wisdom respected throughout the Hélade, destroying its temples and works of art.

Bishop Theophilus, patriarch of Alexandria, initiates persecutions of the adepts of classical culture, inaugurating in Alexandria a period of real battles on the streets. He converts the temple of the god Dionysus into a church, destroys the temple of Zeus, burns the Mithraic and profanes the cult images. The priests are humiliated and mocked publicly before being stoned.

391

A new decree of Theodosius specifically prohibits looking at the shattered statues! The persecutions in the whole empire are renewed. In Alexandria, where the tensions were always very common, the Hellenistic minority, headed by the philosopher Olympius, carries out an anti-Christian revolt.

After bloody street fights with dagger and sword against crowds of Christians who outnumber them greatly, the Hellenists entrench themselves in the Serapeum, a fortified temple dedicated to the god Serapis. After encircling—practically besieging—the building the Christian mob, under the patriarch Theophilus, breaks into the temple and murder all those present; desecrates the cult images, plunders the property, burns down its famous library and finally throws down all the construction.

It is the famous ‘second destruction’ of the Library of Alexandria, jewel of ancient wisdom in absolutely every field, including philosophy, mythology, medicine, Gnosticism, mathematics, astronomy, architecture or geometry: a spiritual catastrophe for the heritage of the West. A church was built on its remains.

392

The emperor forbids all ancient rituals, calling them gentilicia superstitio, superstitions of the Gentiles.

The persecutions return. The mysteries of Samothrace are bloodily closed and all their priests are killed. In Cyprus, the spiritual and physical extermination is led by the bishops St Epiphanius—born in Judea and raised in a Jewish environment, with Jewish blood himself. The emperor gives carte blanche to St. Epiphanius in Cyprus, stating that ‘those who do not obey Father Epiphanius have no right to continue living on that island’. Thus emboldened, the Christian eunuchs exterminate thousands of Hellenists and destroy almost all the temples of Cyprus. The mysteries of the local Aphrodite, based on the art of eroticism and with a long tradition, are eradicated.

In this fateful year there are insurrections against the Church and against the Roman Empire in Petra, Areopoli, Rafah, Gaza, Baalbek and other eastern cities. But the Eastern-Christian invasion is not going to stop at this point in its push towards the heart of Europe.

393

The Olympic Games are banned, as well as the Pythia Games and the Aktia Games. The Christians must have sensed that this Aryan cult for ‘profane’ and ‘mundane’ sports of agility, health, beauty and strength must logically belong to the Greco-Roman culture, and that sport is an area where Christians of the time could never reign. Taking advantage of the conjuncture, the Christians plunder the temple of Olympia.

394

In this year all gymnasiums in Greece are shut down by force. Any place where the slightest dissidence flourishes, or where unchristian mentalities thrive, must be shut down. Christianity is neither a friend of the muscles nor of athletics; or of triumphant sweat: but of the tears of impotence and of terrifying tremors.

That same year, Theodosius removed the statue of Victory from the Roman Senate. The war of the statues thus ended: a cultural conflict that pitted Hellenist and Christian senators in the Senate, removing and restoring the statue numerous times. The year 394 also saw the closing of the temple of Vesta, where the sacred Roman fire burned.

395

Theodosius dies, being succeeded by Flavius Arcadius (reigned between 395-408). This year, two new decrees reinvigorate the persecution. Rufinus, eunuch and prime minister of Arcadius, makes the Goths invade Greece knowing that, like good barbarians, they will destroy, loot and kill. Among the cities plundered by the Goths are Dion, Delphi, Megara, Corinth, Argos, Nemea, Sparta, Messenia and Olympia. The Goths, already Christianized in Arianism, kill many Greeks; set fire to the ancient sanctuary of Eleusis and burn all its priests, including Hilary, priest of Mithras.

The emperor Arcadius. At first glance an eunuch,

a brat, especially when compared to the Roman emperors

and soldiers of yore.

396

Another decree of the emperor proclaims that the previous culture will be considered high treason. Most of the remaining priests are locked in murky dungeons for the rest of their days.

397

The emperor literally orders to demolish all the remaining temples.

398

During the Fourth Ecclesiastical Council of Carthage (North Africa, now Tunisia) the study of Greco-Roman works is forbidden to anyone, even the Christian bishops themselves.

399

The emperor Arcadius, once again, orders the demolition of the remaining temples. At this point, most of them are in the deep rural areas of the empire.

400

Bishop Nicetas destroys the Oracle of Dionysus and forcibly baptizes all non-Christians in the area. By this final year of the fourth century, a definite Christian hierarchy has already been established which includes priests, bishops, archbishops of larger cities and the patriarchs: the archbishops responsible for major cities, namely Rome, Jerusalem, Alexandria and Constantinople.

To this image of a priestess of Ceres, the Roman Demeter, goddess of agriculture and grain, patiently carved on ivory around the year 400 and of an unprecedented beauty, the Christians mutilated her face and threw it into a well in Montier-en-Der, a later abbey in the northeast of France.

It is possible that the image was not thrown into the pit because of hatred (the Christians were more prone to directly destroy), but that the owners got rid of her for fear that the religious authorities would find it. Impossible to know the amount of artistic representations, even superior to this one in beauty, that were destroyed, and of which nothing has remained.

Note of the Ed.: After the centuries, Europeans even forgot how the Greco-Roman sculptures that were destroyed looked like. My guess is that Constantine’s bishops were not Aryans. Destroying a representation of the beauty of the Aryan physique was part of the Semitic takeover of white society: Let’s destroy your self-image as a means to undermine your self-esteem. Something similar is happening today with the religion of Holocaustianity: Let’s undermine your self-image from a decent person to historic grievances so that you may accept masses of non-white immigrants.

Note of the Ed.: After the centuries, Europeans even forgot how the Greco-Roman sculptures that were destroyed looked like. My guess is that Constantine’s bishops were not Aryans. Destroying a representation of the beauty of the Aryan physique was part of the Semitic takeover of white society: Let’s destroy your self-image as a means to undermine your self-esteem. Something similar is happening today with the religion of Holocaustianity: Let’s undermine your self-image from a decent person to historic grievances so that you may accept masses of non-white immigrants.