Today, as I finished reproducing my extracts from the first volume of Kriminalgeschichte, I would like to clarify something.

There was a time when I wanted to add to my excerpts the hundreds of footnotes that appear in Karlheinz Deschner’s book but I changed my mind: mere excerpts do not require the notes, especially in a blog. However, I must point out that there are bibliographical references in a book that the English speaker can read in his native language.

I am referring to Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World: an elegant book published last year in Britain and available this year, in addition, by an American publisher.

Deschner was an obsessive scholar who worked to the nitty-gritty, nose-to-the-grindstone level throughout his life. Although The Darkening Age is not as monumental as Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, I will reproduce Nixey’s preface and the third part of her Introduction. It is vital that English speakers know that we are not inventing a black history of Christianity. Some of the main references that support what we have been saying with the translations of Deschner and Evropa Soberana, also appear in Nixey’s book.

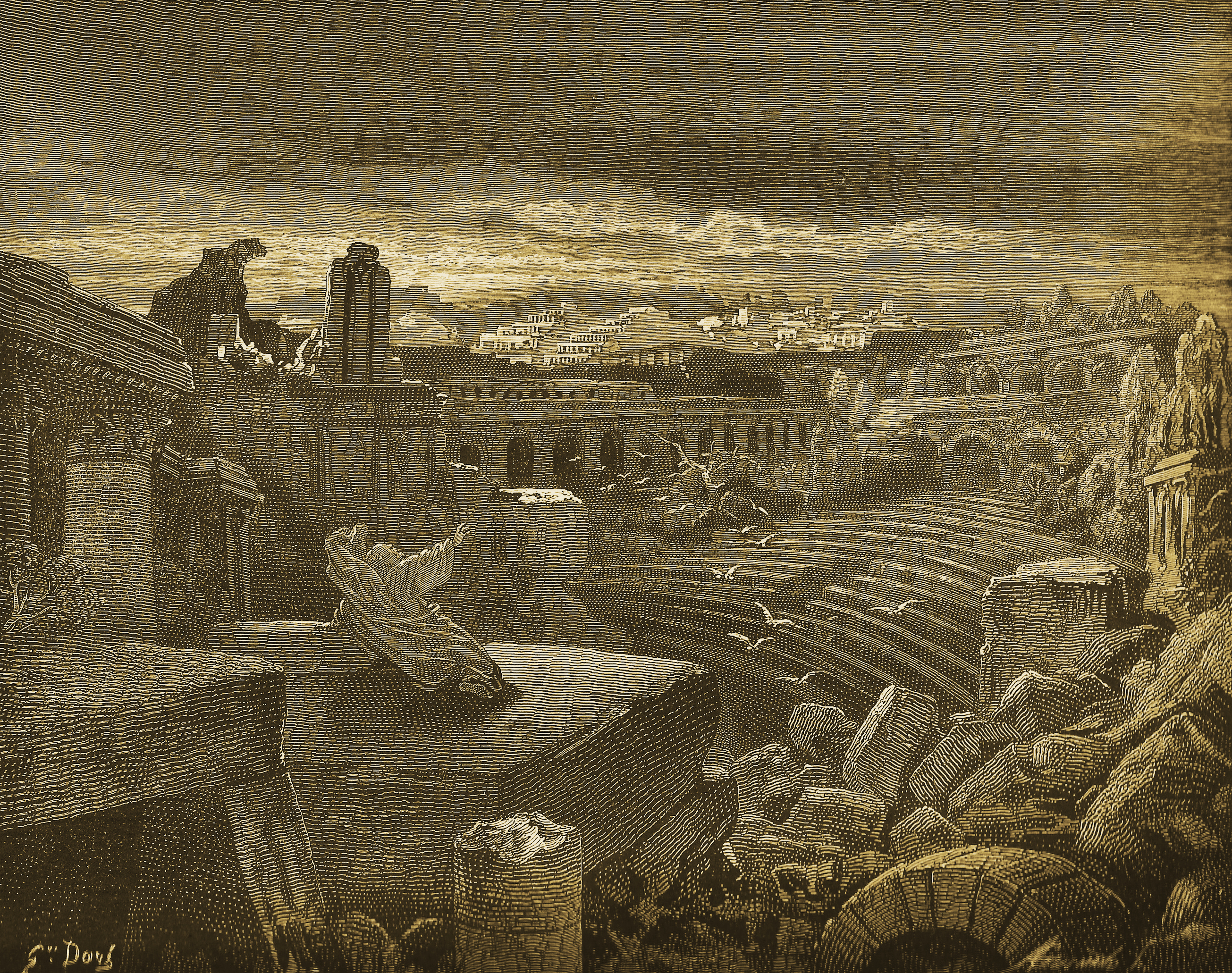

What is more, if you search you will find that even The Reader’s Digest which publishes copiously illustrated books for the simple, and very Christian, American families acknowledges the facts. For example, the image below shows a crowd of Christians who, encouraged by Pope Theophilus of Alexandria, destroyed the temple of Serapis in 391.

I scanned that image from pages 242-243 of the translation from English into Spanish of After Jesus (The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc., 1992). What we see in the illustration represents the first dark hour of the West: the era that saw the destruction of ancient knowledge in the Library of Alexandria. Now we are living the second dark hour, when the enemy attacks directly your DNA so that the West cannot recover again, not even after a dark age as it did in the Renaissance.

That’s why I call ‘darkest hour’ to our times.

About the first dark hour, of the authors I have quoted and will continue to quote, Soberana, Deschner and Nixey are gentiles. But yesterday almost midnight a commenter called my attention to Suicide Note, a book of almost two thousand pages of Mitchell Heisman (1975-2010). I began to leaf through the Suicide Note chapter on how the Christians installed Semitic malware in the psyche of the Romans to move them to commit ethnic suicide.

I was fascinated and continued reading until almost two in the morning today. However, when I wanted to inquire about the author via Google, I discovered that Heisman was a Jew who committed suicide upon finishing the book!

Of the German Deschner, the English Nixey and the Spaniard Soberana, only the latter awoke about the Jewish question. It is really curious that, although neither Deschner nor Nixey took the red pill, an American Jew did take it.

The PDF of Suicide Note is available online for anyone who wants to read the whole thing. Tomorrow I’ll start reproducing those passages that elucidate what we have been saying about the Christian problem. Of course: I have to place the star of David after the author’s name. It is very rare for a Jew to say anything about the psyop that his tribe applied to the Aryan since the origins of Christianity. One of them is Heisman✡.

Trouble is that most white nationalists still don’t want to see what even a kike saw just before blowing his brains…

Category: Christendom

Below, an abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity). For a comprehensive text that explains the absolute need to destroy Judeo-Christianity, see: here. In a nutshell, any white person who worships the god of the Jews is, ultimately, ethnosuicidal.

Augustine sanctions the ‘holy war’

The amantissimus Domini sanctissimus, as the bishop Claudius of Turin of the 9th century called Augustine, recorded, like no one before him, the compatibility between service to war and the doctrine of Jesus.

The father of the Church Ambrose had already celebrated a pathetic instigation of war, and the father of the Church Athanasius had declared that in war it was ‘legal and praiseworthy to kill adversaries’. However, none of them admitted the bloody office with as few scruples and as the hypocrite ‘angel of heaven’ who looks ‘constantly to God’.

Certainly, Augustine did not share the optimism of an Eusebius or an Ambrose, who equated the hope of the pax romana with that of pax christiana as providential, since ‘The wars to the present are not only between empires but also between confessions, between truth and error’. By weaving his web of grace, predestination and angels, Augustine theoretically committed himself in an increasingly negative way before the Roman state.

Every State power based on the libido dominandi rests on sins and for that reason must submit to a Church based on grace, but in fact not free of sin either. This philosophy of the State, which constituted the historical-philosophical basis of the medieval power struggle between the popes and the emperors, was decisively influential until the times of Thomas Aquinas.

Until the year of his death, Augustine not only asked for the punishment of the murderers, but also to crush the uprisings and subdue the ‘barbarians’, taking it as a moral obligation. It was not difficult for him to consider the State malignant but he praised its bloody practices and, like everything else, also ‘attribute it to Divine Providence’ since ‘its way of proceeding’ is ‘to avoid human moral decay through wars’.

Whoever thinks so, in a childlike and cynical way at the same time, obviously interprets in the same sense the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’. That commandment should not be applied to the totality of nature and the animal kingdom. Augustine discusses with the Manichaeans that it does not include the prohibition of ‘pulling a bush’ or the ‘irrational animal world’ because such beings ‘must live and die to our advantage; submit them to you!’

‘Man owns animals’, complains Hans Henny Jahnn in his great trilogy Fluss ohne Ufer. ‘He does not need to try. He just has to be naive. Naive also in his anger. Brutal and naive. This is what God wants. Even if he hits the animals, he will go to heaven’.

Earlier, authors such as Theodor Lessing and Ludwig Klages had persuasively shown that, as the latter affirms, Christianity conceals something with its connotation of ‘humanity’. What it really means is that the rest of living beings lack value—unless they serve human beings! They write: ‘As is well known, Buddhism prohibits the killing of animals, because the animal is the same being as we are. Now, if one scolds an Italian with such a reproach when he torments an animal to death, he will claim that “senza anima” and “non è christiano” since for the Christian believer the right to exist lies only in the human beings’.

Augustine on the other hand believes that the human being ‘even in situations of sin is better than the animal’: the being ‘of lower rank’. And he treats vegetarianism as ‘impious heretic opinion’.

That God can be pleased with arms is shown by the example of David and that of ‘many other righteous’ of that time. Augustine quotes at least 13,276 times the Old Testament, about which he had previously written that he had always found it unpleasant!

But now it was useful. For example: ‘The just will rejoice when contemplating revenge; He will bathe his feet in the blood of the wicked’. And of course all the ‘just’, logically, can make a ‘just war’ (bellum iustum).

It is a concept introduced by Augustine. No Christian had used it before, not even the easy-going Lactantius, whom he read carefully. Soon the whole Christian world made a iusta bella, based upon a ‘just’ reason for war any minimal deviation from the Roman liturgy. Augustine strongly recommends military service, and cites quite a few cases of ‘God-fearing warriors’ from the Bible; not only the ‘numerous righteous’ of the Old Testament, so rich in atrocities, but also a couple of the New Testament.

Augustine experienced the collapse of Roman rule in Africa, when the Vandal hordes invaded Mauritania and Numidia in the summer of 429 and in the spring of 430. He witnessed the annihilation of his life’s work: whole cities were grass of the flames and its inhabitants assassinated. Anywhere the Catholic communities, depleted by the Church and the State, opposed no resistance; at least there is no relation of it.

Augustine died on August 28, 430, and was buried that same day. A year later Hippo, retained by Boniface for fourteen months, was evacuated and partially burned. Augustine’s biographer, the holy bishop Possidius, who like the teacher was a fervent fighter against the ‘heretics’ and the ‘pagans’, still lived some years among the ruins.

END OF VOLUME I

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support this site.

A 17th-century Calvinist print depicting Pelagius

The caption says:

Accurst Pelagius, with what false pretence

Durst thou excuse Man’s foul Concupiscence,

Or cry down Sin Originall, or that

The Love of GOD did Man predestinate.

The overthrow of Pelagius

Rather than the struggle against the Donatists, Augustine was internally motivated by the prolonged quarrel with Pelagius, who convincingly refuted his bleak complex of original sin, along with the mania of predestination and grace; the Council of Orange of the year 529 dogmatized it (partly literally) and the Council of Trent renewed it.

According to most sources, Pelagius was a Christian layman of British origin. From approximately the year 384, or sometime later, he imparted his teachings in Rome, enjoying great respect.

Interestingly, when he disembarked at Hippo in 410, Pelagius was in the retinue of Melania the Younger, her husband Valerius Pinianus and her mother Albina—that is, ‘perhaps the richest family in the Roman Empire’ (Wermelinger). The father of the Church, Augustine, had also intensified his contacts with this family for a short time. Indeed, he and other African bishops, Aurelius and Alypius, had convinced the billionaires not to squander their wealth with the poor, but to hand them over to the Catholic Church! The Church became heir to this gigantic wealth. Melania was even elevated to sanctity (her holiday: December 31). ‘How many inheritances the monks stole!’, writes Helvetius, ‘but they stole them for the Church, and the Church made saints of them’.

From Pelagius, a man of great talent, we have received numerous short treatises, whose authenticity is subject to controversy. However, there are at least three that seem authentic. The most important of his works, De natura, we know by the refutation of Augustine, De natura et gratia. Also the main theological work of Pelagius, De libero arbitrio has been transmitted to us, in several fragments, by his opponent, although his theory is often distorted in the course of the controversy.

Pelagius, impressive as a personality, was a convinced Christian; he wanted to stay within the Church and what he least wanted was a public dispute. He had many bishops on his side. He did not reject prayers or deny the help of grace, but rather defended the need for good works, as well as the need for free will, the liberum arbitrium. But for him there was no original sin: the fall of Adam was his own; not hereditary.

It was precisely his experience with the moral laziness of the Christians that had determined the position that Pelagius adopted, in which he also often included an intense social criticism tainted with religiosity, appealing to Christians to ‘feel the pains of others as if they were their own, and shed tears for the affliction of other human beings’.

But this was not, of course, a subject for the irritable Augustine; he, who did not see the human being, like Pelagius, as an isolated individual but devoured by a monstrous hereditary debt, the ‘original sin’, and considered humanity a massa peccati, fallen because of the snake, ‘an elusive animal, skilled on the sinuous roads’, fallen because of Eve, ‘the smaller part of the human couple’ because, like the other fathers of the Church, he despised the woman.

In strict justice, all mankind would be destined for hell. However, by a great mercy there would be at least a minority chosen for salvation, but the mass would be rejected ‘with all reason’.

There is God full of glory in the legitimacy of his revenge.

According to the doctor ecclesiae we are corrupted from Adam, since the original sin is transmitted through the reproductive process; in fact, the practice of the baptism of children to forgive sins already presupposes those in the infant. On the other hand, the salvation of humanity depends on the grace of God, the will has no ethical significance.

But in this way the human being becomes a puppet that is stirred in the threads of the Supreme: a machine with a soul that God guides as he wants and where he wants, to paradise or to eternal perdition. Why?

Why? Because he wanted. But why did he want it? ‘Man, who are you who want to talk to God?’

Augustine warned against Pelagius and launched, increasingly busier in the causa gratiae, his theory of predestination which Jesus does not announce and which he himself did not defend in his early days, for more than a decade and a half, until the year 427, when he published a dozen controversial writings against Pelagius.

St. Jerome, at odds with the Bishop of Jerusalem, then wrote a very wide-ranging polemic, the Dialogi contra Pelagianos, in which he defamed his adversary by calling him a habitual sinner, arrogant Pharisee, ‘greasy dog’, etc.: dialogues that Augustine extolled as a work of wonderful beauty and worthy of faith. In 416 the Pelagians set fire to the monasteries of Jerome, and his life was in grave danger.

Pope Zosimus was left out of play in a clever stratagem of Emperor Honorius, and in a letter addressed on April 30, 418 to Palladius, prefect praetorian of Italy, he ordered the expulsion of Pelagius and Caelestius from Rome—the harshest decree by the end of the Roman Empire. He also censured his ‘heresy’ as a public crime and sacrilege, with a special emphasis on the expulsion from Rome, where there were riots and violent disputes among the clergy. All the Pelagians were persecuted, their property was confiscated and they were exiled.

In the final phase of the conflict the young bishop Julian of Eclanum (in Benevento) became the great adversary of Augustine, who by age could have been a son: the authentic spokesman of the opposition, who often cornered the bellicose African through a frontal attack.

Julian was probably born in Apulia, at the bishop’s headquarters of his father Memor, who was a friend of Augustine. As a priest he married the daughter of a bishop, and Pope Innocent appointed him in 416 as bishop of Eclanum. Unlike most prelates, he had an excellent education, was very independent as a thinker and very sharp as a polemicist. He wrote for a ‘highly intellectual’ audience, while Augustine, who found it difficult to refute the ‘young man’, did so for the average clergy, who always constitute a majority.

Although he theologically subscribes the theory of grace, he does not see it as a counterpart of nature, which would also be a valuable gift of the Creator. He highlighted free will, attacked the Augustinian doctrine of original sin as Manichaean, fought the idea of inherited guilt, of a God who becomes a persecutor of newborns, who throws into eternal fire little children—the God of a crime ‘that can scarcely be imagined among the barbarians’ (Julian).

Along with the eighteen bishops who gathered around him, Julian was excommunicated in 418 by Zosimus and, like most of them, expelled from his position, he found refuge in the East. Augustine became more and more severe in his assertions about predestination, the division of humanity between the elect and the condemned. Already on his deathbed, he attacked Julian in an unfinished work.

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support this site.

Below, an abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity). For a comprehensive text that explains the absolute need to destroy Judeo-Christianity, see here. In a nutshell, any white person who worships the god of the Jews is, ultimately, ethnosuicidal.

Augustine’s campaign against the Donatists

To the Donatists, whom the African had never mentioned before, he finally paid attention when he was already a priest. Since then he fought them year after year, with greater fury than other ‘heretics’; he threw his contempt to their faces and expelled them from Hippo, their episcopal city. Because the Donatists had committed ‘the crime of schism’ they were nothing but ‘weeds’, animals: ‘these frogs sit in their pond and croak: “we are the only Christians!” but they are heading to hell without knowing it’.

What was a Donatist for Augustine? An alternative that was not presented to him, because, when he was elected bishop, the schism was already 85 years old. It was a local African issue, relatively small, though not divided into ‘countless crumbs’ as he claimed. Catholicism, on the other hand, absorbed the peoples; it had the emperor on his side, the masses, as Augustine blurts out, ‘the unity of the whole world’. Frequently and without hesitation Augustine insists on such demonstration of the majority, incapable of making the reflection that Schiller will later formulate: ‘What is the majority? Most is nonsense; intelligence has always been only in the minority’.

The Donatist was convinced of being a member of a brotherhood. Throughout their tragic history, they collaborated with a religious-revolutionary peasant movement, which inflicted vexations on the landowners: the Circumcellions or Agonistici—temporary workers of the countryside and at the same time the left wing of this Church, who first enjoyed the support of Donatus of Bagai and later that of Gildo.

According to his adversary, Augustine, who characterized them with the psalm of ‘rapids are their feet to shed blood’, they robbed, looted, set fire to the basilicas, threw lime and vinegar in the eyes of Catholics, claimed promissory notes and started with threats his emancipation. Often led by clerics, including bishops, ‘captains of the saints’, these Agonistici or milites Christi (followers of martyrs, hobby pilgrims, terrorists) beat the landowners and Catholic clerics with decks called ‘israels’ under the war cry of ‘Praise be to God’ (laus deo), the ‘trumpets of the massacre’ (Augustine). The Catholics ‘depended to a great extent on the support of the Roman Empire and the landlords, who guaranteed them economic privileges and material protection’ (Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum). It was also not uncommon for the exploited to kill themselves in order to reach paradise. As the Donatists said, because of the persecution they jumped from rocks, as for example the cliffs of Ain Mlila, or to mighty rivers, which for Augustine was not more than ‘a part of their habitual behaviour’.

The centre of their offices was the cult to the martyrs. Excavations carried out in the centre of Algeria, which was the bulwark of the Donatists, have brought to light innumerable chapels dedicated to the adoration of the martyrs and which undoubtedly belonged to the schismatics. Many carried biblical quotes or their currency, Deo laudes.

A Donatist bishop boasted that he had reduced four churches to ashes with his own hand. They, as so often emphasized, even by Augustine, could not be martyrs ‘because they did not live the life of Christ’. The true background of the Donatist problem, which not only led to the religious wars of the years 340, 347 and 361-363 but caused the great uprisings of 372 and 397-398, Augustine failed to understand or did not want to understand. He thought he could explain through a theological discussion what was less a confessional than a social problem: the deep social contrasts within North African Christianity, the abyss between a rich upper class and those who owned nothing; that they were not in any way just the ‘bands of Circumcellions’, but also the slaves and the free masses who hated the dominant ones.

Augustine did not know or did not want to see this. He defended with all tenacity the interests of the possessing and dominant class. For him the Donatists were never right: they simply defamed and lied. He maintained that they were looking for a lie, that their lie ‘fills all Africa’. Initially, Augustine was not in favour of violence. He questioned any attempt to use it. ‘I have no intention of forcing anyone against their will to the religious community with anyone’. Of course, when he learned about the wickedness of the ‘heretics’ and saw that they could be improved with some force, which the Government already commissioned in an increasing way from the year 405, he changed his mind.

The faith of the Donatists, no matter how similar it was—even, essentially, identical—was nothing but error and violence. Catholics, on the other hand, only acted out of pure compassion, out of love. ‘Understand what happens to you! God does not want you to sink into a sacrilegious disunity, separated from your mother, the Catholic Church’.

As the Handbuch der Kirchengeschichte says, or more precisely, the Catholic Baus, ‘here speaks the voice of a man who was so driven and encouraged by the religious responsibility to bring back to an ecclesia the lost brothers in the error, that all the other considerations remained for him in the background’. How typical! He must exonerate Augustine, make his thoughts and actions understandable. Thus, over the course of two millennia, the great crimes of history have been constantly apologised and exalted; they have been glorified. Only in the name of God can they always allow and commit certain crimes, the most atrocious, as will be demonstrated more clearly each time throughout this criminal history.

With an extensive series of astute sentences, without missing those corresponding to the Old and New Testaments, the great lover now demands coercive measures against all those who ‘must be saved’ (corrigendi atque sanandi). The coercion, Augustine teaches now, is sometimes inevitable, because although the best ones can be handled with love, to the majority, unfortunately, it is necessary to force them with fear.

‘He who spares the rod hates his son’ he says, quoting the Bible. ‘A spoiled man is not corrected with words’. And did not Sara chase Hagar? And what did Elijah do with the priests of Baal? For many years Augustine had justified the brutalities of the Old Testament against the Manichaeans, from whom came that book of princes of darkness.

The New Testament could also be used. Did not Paul also give some people to Satan? ‘You know?’, Augustine says to bishop Vixens, explaining the Gospel—:

no one can be forced to justice when you read how the head of the family spoke to his servants: ‘Whoever finds them compels them to enter!’

—which Augustine translates most effectively as ‘force them’ (cogitere intrare). Resistance only demonstrates irrationality. Do not the feverish patients, in their delirium, also revolt against their doctors? Augustine calls tolerance (toleratio) ‘fruitless and vain’ (infructuosa et vana) and is excited by the conversion of many ‘through healthy coercion’ (terrore perculsi). It was nothing else than the program of Firmicus Maternus, ‘the program of a general declaration of war’ (Hoheisel), whether Augustine had read it or not.

‘Under extreme coercion’, the ‘professional speaker’ preaches, rich in tricks, ‘the inner will is realised’, referring to the Acts of the Apostles, 9,4, to John, 6,44, and finally, starting from the year 416-417, to Luke, 14, 23—the Gospel of love! In proceeding against his enemies, he gave the impression that he was also ‘sometimes a little nervous’ (Thomas), although what seemed to be persecution, in reality, was only love, ‘always only love and exclusively love’ (Marrou).

‘The Church presses them against their hearts and surrounds them with motherly tenderness to save them’—through forced labour, fustigations, confiscation of property, elimination of the right of inheritance. However, the only thing that Augustine wants again is to ‘impose’ on the Donatists ‘the advantages of peace, unity and love’:

That is why I have been presented to you as your enemy. You say you want to kill me, although I only tell you the truth and, as far as I’m concerned, I will not let you get lost. God would avenge from you and kill, in you, the error.

God would take revenge on you! The bishop does not consider himself by any means an inciter. But, yes, when it seemed appropriate, he demanded to apply the full weight of the law to the recalcitrant, not granting them ‘grace or forgiveness’. Better said, he authorized torture!

The most famous saint of the ancient Church, perhaps of the whole Church, a ‘so affable person’ (Hendrikx), the father of ‘infinite kindness’ (Grabmann) ‘and generosity ‘(Kotting), who against the Donatists ‘he constantly practiced the sweet behaviour’ (Espenberger), which against them does not formulate ‘any hurtful word’ (Baus), which tries to ‘preserve from the harsh penalties of Roman law’ even ‘the guilty’ (Hümmeler)—in short, the man who becomes spokesman of the mansuetudo catholica, of Catholic benevolence, allows torture…

The thing was not so bad after all! ‘Remember all the possible martyrdoms’, Augustine consoles us:

Compare them with hell and you can imagine everything easily. The torturer and the tortured are here ephemeral, eternal there… We have to fear those pains as we fear God. What the human being suffers here supposes a cure (emendatio) if it is corrected.

Catholics could thus abuse as much as they liked, it was unimportant compared to hell, with that horror that God would impose upon them for all eternity. The earthly torture was ‘light’, ‘transient’, just a ‘cure’!

A theologian is never disconcerted! That’s why he does not know shame either.

In the Christian Empire of those times there prevailed everything except liberality and personal freedom. What prevailed was slavery, children were chained instead of the parents, everywhere there was secret police, ‘and every day could be heard the cries of those whom the court tortured and could be seen the gates with the whimsically executed’ (Chadwick). The emperor’s assassins automatically liquidated the Donatists who had mutilated Catholic priests or who had destroyed churches. Augustine endorsed in practice the death penalty. ‘The greater the hardness with which the State acts, the more Augustine applauds’ (Aland).

Here we see the celebrated father of the Church in all its magnitude: as a desk author and hypocrite; as a bishop who not only exerted a terrible influence during his life, but who was the initiator of political Augustinism: the archetype of all the bloody inquisitors of so many centuries, of their cruelty, perfidy, prudishness, and a precursor of horror: of the medieval relations between Church and State. Augustine’s example allowed the ‘secular arm’ to throw millions of human beings, including children and the elderly, dying and disabled, to the cells of torture, to the night of the dungeons, to the flames of the fire—and then hypocritically ask the State to respect their lives! All the henchmen and ruffians, princes and monks, bishops and popes who from now on would hunt martyrs and burn ‘heretics’, could lean on Augustine, and in fact they did it; and also the reformers.

Here we see the celebrated father of the Church in all its magnitude: as a desk author and hypocrite; as a bishop who not only exerted a terrible influence during his life, but who was the initiator of political Augustinism: the archetype of all the bloody inquisitors of so many centuries, of their cruelty, perfidy, prudishness, and a precursor of horror: of the medieval relations between Church and State. Augustine’s example allowed the ‘secular arm’ to throw millions of human beings, including children and the elderly, dying and disabled, to the cells of torture, to the night of the dungeons, to the flames of the fire—and then hypocritically ask the State to respect their lives! All the henchmen and ruffians, princes and monks, bishops and popes who from now on would hunt martyrs and burn ‘heretics’, could lean on Augustine, and in fact they did it; and also the reformers.

When in 420 the state minions persecuted the bishop of Ta-mugadi, Gaudentius, he fled to his beautiful basilica; fortified himself there and threatened to burn himself along with his community. The chief of the officials, a pious Christian, who nevertheless persecuted people of his own faith, did not know what party to take and consulted Augustine. The saint, inventor of the sui generis doctrine of predestination, replied:

But since God, according to secret but just will, has predestined some of them to eternal punishment, without a doubt it is better that, although some are lost in their own fire, the vastly greater majority is gathered and recovered from that pernicious division and dispersion, instead of all together be burned in the eternal fire deserved by the sacrilegious division.

Once again Augustine was himself, ‘of course the first theoretician of the Inquisition’, who wrote ‘the only complete justification in the history of the ancient Church’ about ‘the right of the State to repress non-Catholics’ (Brown). In the application of violence, the saint only saw a ‘process of debilitation’, a ‘conversion by oppression’ (per molestias eruditio), a ‘controlled catastrophe’ and compared it to a father ‘who punishes the son who loves’ and that every Saturday night, ‘as a precaution’ beats his family.

The ‘edict of the unit’ of 405 followed other state decrees in the years 407, 408, 409, 412 and 414. The obligatory withdrawal of the Donatists was ordered, their Church was relegated more or less to the underground and they started pogroms that would last several years. The Donatist Church was forbidden; its followers forced to convert to Catholicism. ‘The Lord has shattered the teeth of the lion’ (Augustine). Entire cities, hitherto convinced Donatists, became Catholic out of fear of sorrow and violence, such as the episcopal city of Augustine, where once the ovens could not bake bread for Catholics. Finally, he himself expelled the Donatists. However, when the State tolerated them temporarily during the invasion of Alaric and they returned, for the great saint they seemed ‘wolves to whom it would be necessary to kill with blows’. Only by chance did he escape from an ambush that the Circumcellions had laid out for him.

The masses of slaves and settlers, of whom only their labour force was of any use, were to be maintained within the Catholic Church, through forced labour and the lash of their lords, for the maintenance of ‘Catholic peace’. In the year 414 the Donatists were deprived of all their civil rights and the death penalty was threatened to those who celebrated their religious services. ‘Where there is love, there is peace’ (Augustine). Or as our bishop later declared triumphantly: Quodvult deus de Cartago: the viper has been crushed, or better still: it has been devoured.

After the year 418, the theme of the Donatists disappears for decades from the debates held in the synods of the North African bishops. In 420 it appears the last anti-Donatist writing of Augustine: Contra Gaudentium. In 429, with the invasion of the Vandals, the anti-Donatist imperial edicts also ended, which continued to call for annihilation. However, the schism lasted until the 6th century, although very weakened.

The sad remains that managed to escape the constant persecutions were destroyed a century later, along with Catholics, by Islam. African Christianity was undermined, bankrupt; finally, completely separated from Europe in the religious aspect, and escaped from its area of influence to fall into that of the Near East.

The most important ancient of the Christian churches, the only one in the Mediterranean, disappeared without a trace. There was nothing left of her. ‘But it was not due to Islam but to the persecutions against the Donatists, which made North Africa hate the Catholic Church so much that the Donatists received Islam as a liberation and converted to it’ (Kawerau).

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support The West’s Darkest Hour.

Take your pick

I was amused in the first hours of this day with the classification, in White Right Hub, of several blogsites where we learn that Mark Steyn is a ‘Normie’ and the Zimmermann Blog a ‘Crypto Jew’. There is a useful category, ‘Borderline Alt Right’ that includes Taki’s Magazine. But I especially liked the category ‘Alt Christian Cuck’ which includes the following:

Brother Nathanael

Lasha Darkmoon

Millennial Woes

Occidental Dissent

Political Cesspool Radio Show

Thermidor

Vox Popoli

What I enjoyed the most, however, is the classification of Ned May’s blogsite Gates of Vienna as ‘Gates of Tel Aviv’! According to the criterion of the admin non-labelled sites, which includes my own one, apparently are okay.

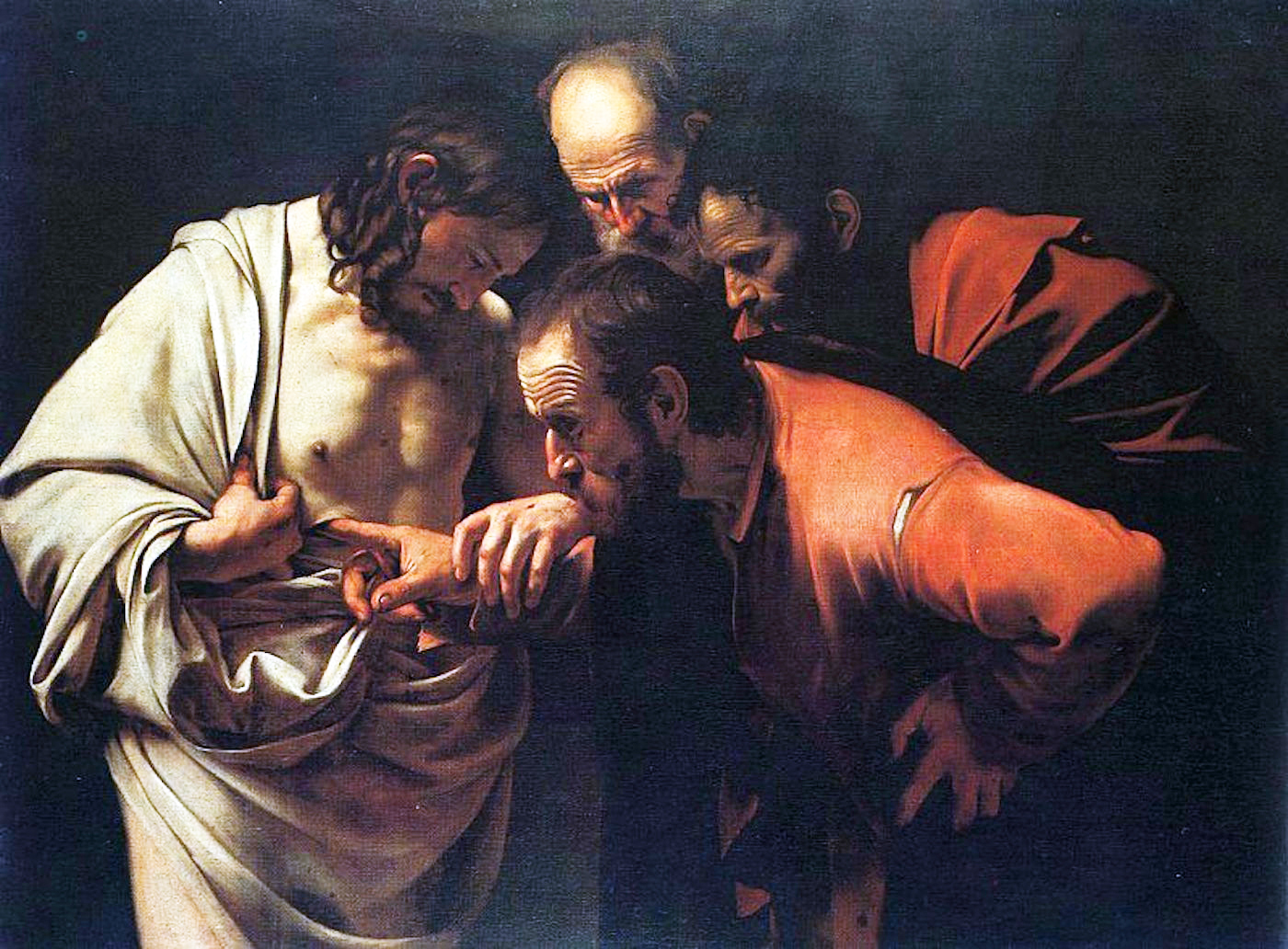

People do not know how the mind works. Virtually all white nationalists who are Christians believe that the stories of the Resurrection have to do with the empirical world: an event in 1st-century Palestine. Now comes to my mind an oil painting of the risen Jesus that Andrew Anglin chose for his Daily Stormer in the days of Easter a few years ago.

In reality, the stories about Jesus that Christians believe, and revere, have nothing to do with the empirical world but with the structure of the inner self. I’m not going to give a class in this post about what introject means, or how our parents can program us malware without us knowing. Suffice it to say that, in my long odyssey in the fight against dad’s introjects, I had to read a lot of literature to convince myself that what the Gospels say must be questioned.

The resurrection of Jesus

The ordinary Christian does not have the faintest idea of the studies about the narratives of what they call the Resurrection and the Pentecost apparitions—research by those who have taken the trouble to learn ancient Greek to make a meticulous examination of the New Testament. The way secular criticism sees all these Gospel stories is complicated, but I will summarise it here in the most didactic way possible.

The oldest texts of the New Testament, like one of the Pauline epistles to the Corinthians, better reflect the theology of original Christianity than the late texts. Therefore, it is important to note that Paul does not mention the empty tomb or the ascension of Jesus. Modern criticism says that, if Paul’s epistle to the Corinthians was written by the 60s of our era, in that decade these legends had not yet unfolded.

Of the evangelists, Mark is the oldest and John the latest. (The Christian churches confuse the order in their Bibles by placing the Gospel of Matthew before Mark.) As Matthew and Luke copied and pasted a lot of verses from the Gospel of Mark when putting together their own gospels, these three evangelists are known as the Synoptics to distinguish them from the fourth gospel. Take this very seriously to see how the writers of the New Testament were adding narrative layers throughout the 1st century. To the brief visions that Paul had, collected in his first epistles some three decades after the crucifixion, in the 60s, the Synoptic evangelists were adding greater legends in the following decades and, in the case of John already in the dawn of the 2nd century of our era, more sophisticated Christologies.

I said that the oldest texts of the badly ordained New Testament in the traditional Bible are some of the epistles of Paul, who, while mentioning the ‘risen Christ’, does so within his dense and impenetrable theology. The Paul question is very important. Unlike the apostles, he never met Jesus in flesh; he only claimed that he heard his voice in a rare vision he had on the road to Damascus. And it is this little fellow who never knew Jesus the first one to speak of the ‘risen Christ’ in a chronologically ordered New Testament.

Unlike Paul the author of the Gospel of Mark, who wrote after Paul, does mention the empty tomb; but not the apparitions of Jesus.[1]

Matthew and John, who wrote after Mark, do mention the risen Jesus speaking with his disciples; but not the Ascension to the heavens.

It is Luke who already mentions everything, although he does not develop Christology at such theological levels as those of John the evangelist.

Another thing that uncultured Christians ignore is that Luke wrote his Gospel and Acts of the Apostles as a single book. The way both Catholic and Protestant churches separate the book of Luke is contrived. And it was precisely Luke who popularized the idea of the Ascension of Jesus: an obviously late legend insofar as, had it been historical, such a Hollywoodesque achievement would have been narrated not only by Paul; but by the other writers of the New Testament epistles, and by Matthew and John the evangelist (and let’s not talk about the other John: John of Patmos, the author of the Book of Revelation).

In short, serious scholars see in the diverse New Testament texts a process of myth-making: literary fiction that, in layers, was developed throughout the 1st century of our era. He who knows the chronology when the books and epistolary of the New Testament were written, and reads the texts in that order—instead of the order that appears in the Bibles for mass consumption—can begin to glimpse the evolution of the myth. Ultimately, there is no valid reason to suppose that what is told in the New Testament about Jesus’ resurrection and apparitions was historical.

It took me years to get oriented in the best literature about the Bible, including everything miraculous that is alleged about Jesus. The truth seeker could consult these selected texts.

____________

NOTE:

[1] To the bare ‘empty tomb’ narrative of the original Markan text in Greek, the church interpolated the verses that, in the common Bibles, we see at the end of Mark’s gospel; but the exegetes detected that trick a long time ago.

Below, an abridged translation from the first volume of

Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums:

Against Hellenism

An anti-Hellenistic law passed the following year sanctions for the offering of sacrifices as a crime of lese-majeste. In case incense was offered, the emperor confiscated ‘all the places that would have been hit by the smoke of the incense’ (turis vapore fumasse). If they were not owned by the person who burned it, he had to pay 25 pounds of gold, as well as the owner. The indulgent administrative chiefs were punished with 30 pounds of gold and their staff was charged the same amount. Geffcken considers this law ‘almost in the tone of a rhetorical missionary sermon’. Gerhard Rauschen speaks of the ‘funeral song of paganism’. It resulted in the prohibition of worship of the gods throughout the Empire.

In this way, many temples were victims of the Christian furore, such as that of Juno Caelestis in Carthage or that of Sarapis in Alexandria. Theodosius, who ‘eliminated the sacrilegious heretics’, as Ambrose praised him in his funeral address, transformed the temple of Aphrodite of Constantinople into a garage. He also threatened with exile or death for performing religious services of the Hellenistic superstition (gentilicia superstitio); it was forbidden to offer incense, light candles, place crowns and even private worship in the house itself. Augustine also praises this fanatic because ‘from the beginning of his government he had been tireless’, ‘helping the threatened (!) Church by very just and merciful laws against the pagans’, and because ‘he had the images of the pagan idols destroyed everywhere’.

But Theodosius repressed Hellenism even through a violent war; in circumstances that, once again, show the behaviour of Ambrose.

(Editor’s Note: Returning to my quotable quote from my previous entry, ‘Only revenge heals the wounded soul’. If whites will survive they must strike back: destroy all the Christian idols in addition to their temples. That alone would heal their psyche from suicidal Judaization: having dared to have a fucking jew as their personal lord and saviour. After three pages describing a bloody episode, Deschner continues:)

Augustine was also glad that the victor overthrew the statues of Jupiter placed in the Alps and that he gave his gold rays ‘gladly and obligingly’ to the messengers of the troops. ‘He had the images of the idols destroyed everywhere, for he had discovered that the granting of the earthly gifts also depends on the true God and not on the demons’. ‘That’s how the emperor was in peace and in war,’ says the devout Theodoret, full of joy. He always asked for God’s help and it was always granted’.

On January 17, 395, at 48 years of age, Theodosius died of dropsy. And Ambrose himself died, on April 4, 397. His remains rest today, which he had never imagined, in a coffin with those of the saints Gervase and Protase.

Below, an abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity). For a comprehensive text that explains the absolute need to destroy Judeo-Christianity, see here. In a nutshell, any white person who worships the god of the Jews is, ultimately, ethnosuicidal.

Ambrose’s struggle against Hellenism

Like many other Church fathers, Ambrose was subject to the influence of Greco-Roman philosophy, especially Plotinus. However, he speaks of it quite critically, relating it to ‘idolatry’, a special invention of Satan, and also to the ‘heretics’, especially the Arians. If this philosophy has something good it is that it comes from the ‘Holy Scriptures’, from Ezra, David, Moses, Abraham and others. It also considers all the natural sciences as an attack on the ‘Deus maiestatis’. The Hellenism is for him, as a whole, an ‘arma diaboli’, and the fight against it ‘a fight against the Empire of the devil’ (Wytzes).

The young Gratian at first had given a good treatment to the Hellenists, but he learned from his spiritual mentor ‘to feel the Christian Empire as an obligation to repress the old religion of the state’ (Caspar). This was no longer difficult, since Christianity was established and paganism was in retreat. After the visit to Rome by Gratian and his co-regent in 376, the city, still largely clinging to the old faith, experienced the destruction of a sanctuary of Mithras by the prefect Gracchus, who, pending baptism, thus demonstrated his merits.

In the summer of 382, Ambrose was in Rome, probably horrified by the many Gentiles, the ‘demented dogs’, as were called by Pope Damasus I, a Spaniard, and while he was talking about persecution, the Christian members of the Senate had to pay their official oath before the image of the goddess Victoria.

At the end of that same year, the sovereign (who would soon be assassinated) disposed, ‘evidently by the advice of Ambrose’ (Thrade), ‘with all certainty not without the influence of his paternal adviser Ambrose’ (Niederhuber), a series of peremptory anti-Hellenist edicts for the city, by virtue of which the support of the State was withdrawn from various cults and clergy, like the popular Vestals, the exemption from taxes was annulled and the ownership of the land of the temples was denied.

The monarch also ordered the removal of the statue of the goddess Victoria, a masterpiece of Tarentum taken from the enemy and also a highly venerated symbol of Roman rule. Since Victoria was one of the oldest national deities, with a cult statue in the Senate hall since the time of Augustus (only Constantius II had recently withdrawn her), most of the senators and Hellenist citizens of Rome felt offended about what was most sacred.

The monarch also ordered the removal of the statue of the goddess Victoria, a masterpiece of Tarentum taken from the enemy and also a highly venerated symbol of Roman rule. Since Victoria was one of the oldest national deities, with a cult statue in the Senate hall since the time of Augustus (only Constantius II had recently withdrawn her), most of the senators and Hellenist citizens of Rome felt offended about what was most sacred.

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support The West’s Darkest Hour.

Guilt

John Canavesio, The Suicide of Judas, ca. 1492: a fresco painting from the Chapel of Notre Dame des Fontaine, France. The painting shows the corpse of Judas, who, overwhelmed by the guilt for having betrayed what many pseudo-racists still call ‘Our Saviour’, had committed suicide. A devil extracts the soul from the body of Judas, presumably to take it to hell.

John Canavesio, The Suicide of Judas, ca. 1492: a fresco painting from the Chapel of Notre Dame des Fontaine, France. The painting shows the corpse of Judas, who, overwhelmed by the guilt for having betrayed what many pseudo-racists still call ‘Our Saviour’, had committed suicide. A devil extracts the soul from the body of Judas, presumably to take it to hell.

The reason why we must destroy Christianity and burn all the churches is that whites, now almost a corpse of what they were, are following the steps of Judas. Even some in the Alt-Right begin, barely, to glimpse it: as Ramzpaul says in his most recent video. There he speaks that a religious guilt, previously controlled by the redeeming figure of Christ, has metastasized into runaway guilt that can only be expiated through ethnic suicide.

There will not be general awakening. Because of Christianity, the devil that took our soul out of our bowels, the white race is doomed to perish. If at least three percent of whites were willing to fight, as Norman Spear says, we would not need to unite the right: only join that three percent. But not even that percentage of whites are willing to give their lives for the cause. A civil war only has chances to occur with the convergence of catastrophes, beginning with the fall of the American dollar.

Even the people of the Alt-Right do not seem to see the degree of nihilistic psychosis in which their race is found. I have not visited Toronto since 1982 but if I did and saw the masses of people of colour that Ramzpaul saw, as he tells us in his most recent video, I would feel a superlative hatred: something that no Alt-Right figure, including Ramzpaul, says publicly.

However, Ramzpaul hits the nail with his comments about guilt. I remember how it lacerated me what my father said to me: that Jesus had died for me. My brother, with such an education, went astray in liberation theology. Let’s visualize Leonardo Boff taking ‘baths of people of colour’ in Brazil, that is, giving us the virtuous signal that he is a holy man. No wonder those who leave the church are left with the worm of guilt and deranged altruism.

I refer to the stupid atheists: those who, stupidly, believe they have abandoned Christianity. They have not. The only thing they have done is going mad like Judas and try to exorcise their guilt in the only way that the secularized Christian ethic allows us: giving their lands and Aryan women to the Other…

Psychologically speaking, the triumph of Judea against Rome is complete. Whites are destined for extinction. Those who have not read Evropa Soberana’s essay will never understand what is happening. And if there are no catastrophes that I predict and the race continues in its guilt path, coloured historians will see that, except this blog, no racist of the 21st century wanted to see what was happening:

It is Xtianity, stupid!

by Ferdinand Bardamu

A Europe without Christianity?

The world of classical antiquity shone as a lamp in the dark, filled with a youthful vigor that ensured its institutions and ideas would endure long after Greece and Rome ceased to exist as viable political entities. Science and reason were then snuffed out by the darkness and imbecility that followed in the wake of Christianity. Libraries were destroyed; art treasures were smashed; building in non-perishable materials almost vanished from memory; personal hygiene disappeared; ignorance was considered a virtue; chaos ensued. This was the triumph of Christianity, a syphilis of the mind that nearly wiped out Western civilization. Although Christian power and influence were shattered long ago by the rediscovery of science and reason, a resurgent Christianity now dominates the West in the form of liberal egalitarianism and cultural Marxism. These philosophies serve as the ideological basis of endless mass Third World immigration and other multiculturalist policies. This neo-Christianity has been imposed on the West by totalitarian liberal-leftist governments.

Understanding Christianity through the prism of group evolutionary strategy can shed light on the significant threat the religion poses to Europeans. As a seminal concept originally formulated by Prof. Kevin MacDonald, it was used with devastating effect in his analysis of 20th century Jewish intellectual and political movements. In a world characterized by in-group ethno-racial preference, absence of a group evolutionary strategy allowing populations at the species and sub-species level to survive and replicate is highly maladaptive.

A group evolutionary strategy is defined as an “experiment in living.” This refers to the establishment of culturally mediated processes or ideological structures that allow humans to exercise control over natural selection at the group level. The basic characteristics of Jewish evolutionary group strategy are:

1.) the rejection of both genetic and cultural assimilation into neighboring populations. Jews in Europe and the Middle East segregated themselves from gentiles by fashioning a distinct identity for themselves. This was accomplished through enforcement of strict endogamy and residential segregation. The genetic relatedness between Jewish groups, such as the Sephardi and Ashkenazi, is higher than between Jews and European populations because of this age-old resistance to assimilation; 2.) successful economic and reproductive competition that has driven Europeans from certain sectors of their own societies (such as finance); 3.) high ethnocentrism; 4.) within-group altruism favoring Jews at the expense of outgroup members, and; 5.) the institutionalization of eugenic practices that selected for high intelligence and conscientiousness in Jewish populations.

In contrast, Christianity undermines group survival by suppressing natural ethnocentric tendencies and maximizing the spread of dysgenic traits. Christianity provides no effective barrier to the cultural and genetic assimilation of Europeans by surrounding non-white populations; for example, during the Spanish and Portuguese colonization of the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Roman Catholic Church aggressively promoted miscegenation among the conquistadores. Ecclesiastical officials encouraged the European colonists to marry and interbreed with their native Indian and African concubines. This resulted in large-scale demographic genocide, which replaced European genetic homogeneity with mestizaje.

That Christianity is a non-ethnocentric ideology based on moral universalism is another serious problem with the religion. Europeans will always champion the interests of hostile out-groups at the expense of fellow Europeans in the name of Christian love and brotherhood. Christianity also opposes the high aggressiveness directed towards outgroup members; instead, believers are expected to practice nonviolence and compassion in the face of demographic replacement. High aggressiveness is a defining feature of Jewish group evolutionary strategy. It has allowed Jews to outcompete Europeans in their own societies.

Lastly, Christianity is militantly anti-eugenic, which is why it allows weaklings to survive and reproduce. This has decreased average IQ and the prevalence of other beneficial traits in European societies. In contrast, Jewish group evolutionary strategy institutionalizes eugenic practices that positively select for these traits, especially high intelligence. These eugenic practices have allowed Jews to exercise a degree of influence over Western societies vastly disproportionate to their actual numbers. Unlike Judaism for Jews, Christianity does not function as a group evolutionary strategy for Europeans, but as a recipe for racial and cultural suicide on a massive scale.

All aggressively pro-active measures against Christianity are certainly ethically justifiable in the face of Western decline and European racial extinction. In this essay, a more scientific approach is recommended. The European intellectual, before he devises any plan of action, must first acknowledge that no other biological process is as important for humans as evolution through natural selection. If he is to have any belief-system, it must be the civil religion of eugenics. Incorporating eugenics into the fabric of civic life would obviate coercion, making racial hygiene a matter of voluntary acquiescence. He would also do well to embrace the trifunctional worldview of the ancient Indo-Europeans.

For many thousands of years, trifunctional ideology served as an effective deterrent to the pathology of moral universalism. By envisaging the tripartite caste system as the fundamental pillar of a new order, the iron law of inequality is exalted as the highest law, the one most conducive to the achievement of social harmony. In this vision, the highest caste, equivalent to the brahman of Aryan-occupied India or the guardians of Plato’s Republic, would be absorbed in scientific and technological pursuits for their own sake. They would be entrusted with the material advancement of civilization. Their moral system, informed by the principles of evolutionary biology and eugenics, would be derived from the following axiom:

What is morally right is eugenic, i.e. improves the race biologically;

what is morally wrong is dysgenic, i.e. degrades the race biologically.

The second class of individuals will be bred for war and the third will consist of industrial and agricultural producers. These correspond to the Aryan kshatriyas and vaishyas or the “silver” and “bronze” castes of Plato’s Republic. Since these individuals do not possess the cognitive ability to participate in the highly abstract civil religion of the brahmans, they will worship their distant ancestors as the racial gods of a new religion founded on eugenic principles.

Christianity is an irrational superstition, which means that its influence will not be mitigated through logical argument. The child-like simplicity of Christian dogma is “a feature, not a bug.” Without an ability to appeal to the lowest common denominator, Christianity would not have spread as rapidly as it did during the 4th century. An enlightened European humanity, educated in the principles of Darwinian evolution and eugenics, cannot co-exist side by side with this ancient Semitic plague. The negative correlation that exists between Christian religiosity and intelligence simply reinforces this conclusion. Christianity is a seemingly intractable problem for primarily eugenic and biological reasons. Although a eugenic approach is clearly needed, other things must be done. If Christianity is to be abolished, all state-sanctioned programs of multicultural indoctrination must be completely eliminated along with it.

Through a program of rigorous eugenic breeding and media control, Europeans will be weaned from the neo-Christian ethical system they have imbibed since childhood. They will come to see eugenics as a necessary form of spiritual transcendence instead. Through a process of evolutionary development that is both culturally and technologically mediated, the lowest castes will embrace the brahman civil religion and see themselves as gods; the more evolved brahmans will move on to a more intensive contemplation of increasingly sophisticated mathematical and scientific abstractions. This progressive development of European racial consciousness will ensure the adoption of a successful group evolutionary strategy among Europeans.

The gradual phasing out of individuals with IQs below 100 will be carried out as an act of religious devotion among the lower castes. Aryan kshatriyas, the “knights of faith” of the new Aryan race religion, will impose a eugenic regime over the entire globe, repopulating the Third World with highly evolved super-organisms that will turn these former hellholes into terrestrial paradises. Wasting precious material resources caring for less evolved members of the human species will be a thing of the past. Humanity, whose scientific and technological progress stagnated during the late 20th century, will once again resume its upward journey toward the stars.

Eugenic breeding will force Europeans to realize the truth of Nietzsche’s core insight: Christianity, a transvaluation of all values driven by ressentiment, is a slave morality. It is the revolt of the underman against the aristocratic Indo-European virtues of strength and magnanimity, pride and nobility. By repudiating the syphilitic poison of Christianity, Europeans will become a race of value-creators, once again in charge of their own destinies as they affirm the beauty of life in all its fullness.

– End of Bardamu’s essay –