For an introduction to these series, see here.

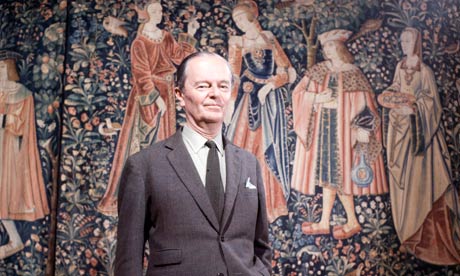

Below, some indented excerpts of “Man—the Measure of all Things,” the fourth chapter of Civilisation by Kenneth Clark, after which I offer my comments.

Ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages:

The Pazzi Chapel, built by the great Florentine Brunellesco in about 1430, is in a style that has been called the architecture of humanism. His friend and fellow-architect, Leon Battista Alberti, addressed man in these words: ‘To you is given a body more graceful than other animals.’

There is no better instance of how a burst of civilisation depends on confidence than the Florentine state of mind in the early fifteenth century. For fifty years the fortunes of the republic, which in a material sense had declined, were directed by a group of the most intelligent individuals who have ever been elected to power by a democratic government. From Salutati onwards the Florentine chancellors were scholars, believers in the studia humanitatis, in which learning could be used to achieve a happy life.

In Florence the first thirty years of the fifteenth century were the heroic age of scholarship when new texts were discovered and old texts edited. It was to house these precious texts, any one of which might contain some new revelation that might alter the course of human thought, that Cosimo de Medici built the library of San Marco. It looks to us peaceful and remote—but the first studies that took place there were not remote from life at all. It was the humanist equivalent of the Cavendish Laboratory. The manuscripts unpacked and studied under these harmonious vaults could alter the course of history with an explosion, not of matter, but of mind.

The discipline of trade and banking, in its most austere form, was beginning to be relaxed, and life—a full use of the human faculties—became more important than making money.

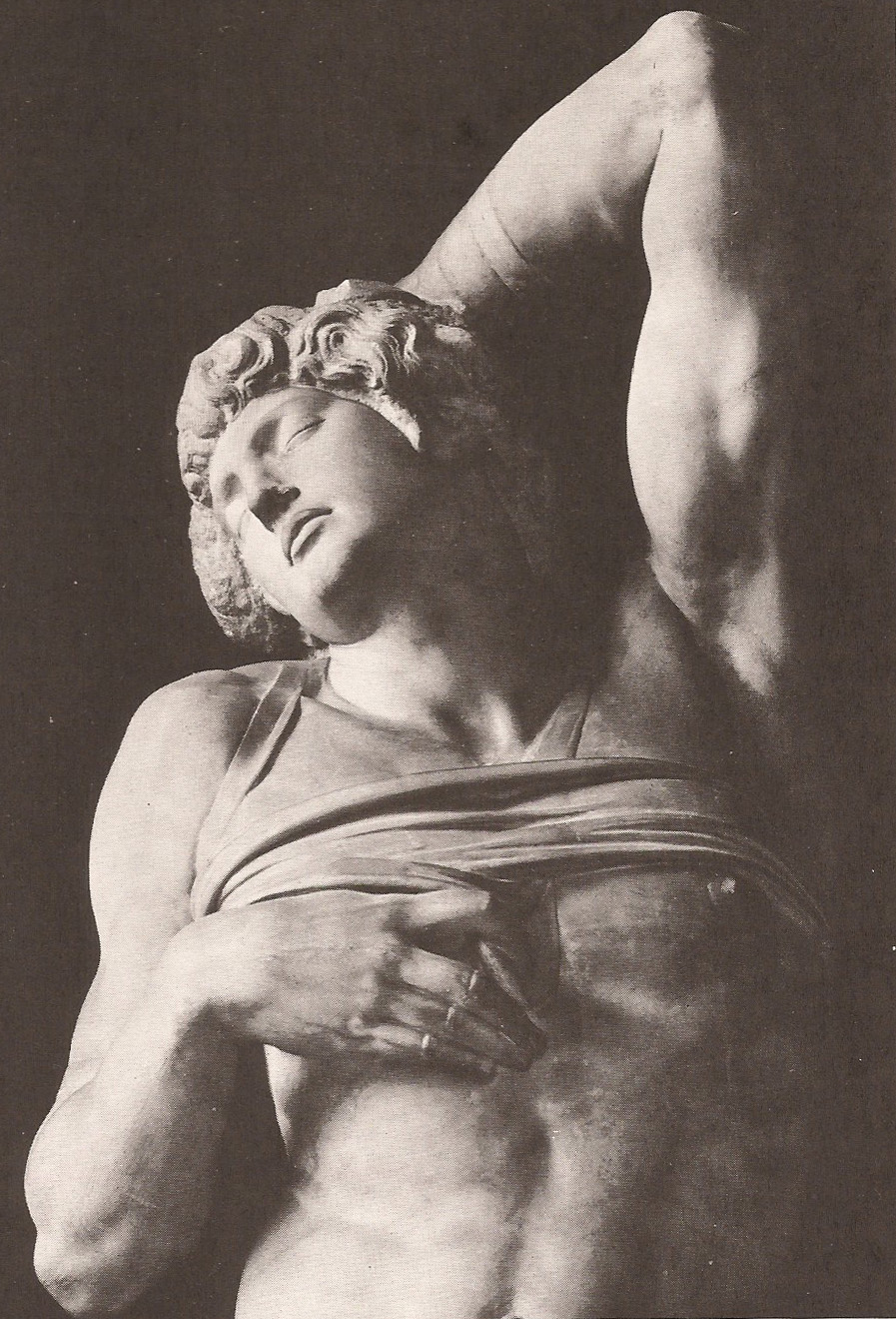

The dignity of man. Today these words die on our lips. But in the fifteenth century Florence their meaning was still a fresh and invigorating belief. Gianozzo Manetti, a humanist man of affection, who had seen the seamy side of politics, nevertheless wrote a book entitled On the Dignity and Excellence of Man. And this is the concept that Brunellesco’s friends were making visible.

Gravitas, the heavy tread of moral earnestness, becomes a bore if it is not accompanied by the light step of intelligence. Next to the Pazzi Chapel are the cloisters of Santa Croce, also built by Brunellesco. I said that the Gothic cathedrals were hymns to the divine light. These cloisters happily celebrate the light of human intelligence, and sitting in them I find it quite easy to believe in man. They have the qualities that give distinction to a mathematical theorem: clarity, economy, elegance.

Alberti, in his great book on building, describes the necessity of a public square ‘where young men may be diverted from the mischievousness and folly natural to their age.’ The early Florentine Renaissance was an urban culture, bourgeois properly so-called. Men spent their time in the streets and squares, and in the shops.

Elsewhere I’ve talked about how the modern world of money is inimical to racial interests. As to date, no white nationalist that I know has criticized the barbarous architecture, symptomatic in the worshiping of the new god of capitalism, so well epitomized in both London and New York: the subject of the last episode of Civilisation.

Together with the degenerate music, TV and Hollywood tastes and sexual lifestyles of some nationalists, architecture is another facet where the uncorrupted individual can read the signs of a decadent society; and why he cannot blame non-gentiles for all our problems when even the nationalists themselves are part of this problem.

Remember Clark’s words in the first episode? “If I had to say which was telling the truth about society, a speech by a Minister of Housing or the actual buildings put up in his time, I should believe the buildings.” One only has to contrast the completely soulless edifices we see everyday going to work with Raphael’s town square and see how extremely degraded, Mammonesque in fact our large cities have become.

In the popular imagination, the extreme examples of this degeneracy are the Foundation novels of Asimov and the latest Star Wars films, where a whole planet has become metropolis: the exact opposite of the most humane sci-fi novels by Arthur C. Clarke where, like the Florentines, the white people lived in small Elysian towns. Architecture today is so degenerate that even Roger Scruton in Why Beauty Matters—a 2009 BBC documentary that, unlike Clark’s Civilisation, is marred by the constant presence of non-whites—pays special attention to the sterile architectural forms of today’s world.

I wish young nationalists became believers in the studia humanitatis and familiarise themselves with those intellectuals in the movement that (like Clark) have a much broader sense of European culture than the common white nationalist blogger. I refer to people like Tom Sunic in Europe and Michael O’Meara in America. Both could help us to leave behind the provincial scene so common in the nationalist sphere as well as the simplistic single-cause hypothesis.

It is true that, unlike the Athenians, fifteenth century Florentines were chiefly interested, like contemporary western man, in making money. But like the Athenians the Florentines… loved beauty. Of the landscapes whose beauty mostly caught my attention during a trip through Europe by train, I still remember the Italian, about which Clark said:

Looking at the Tuscan landscape with its terraces of vines and olives and the dark vertical accents of the cypresses, one has the impression of timeless order. There must have been a time when it was all forest and swamp—shapeless, formless; and to bring order out of chaos is a process of civilisation.

Then, in the first years of the sixteenth century, the Venetian painter Giorgione transformed this happy contact with nature into something openly sensual. The ladies who, in the Gothic gardens, had been protected by voluminous draperies, are now naked; and, as a result, his Fête Champêtre opens a new chapter in European art. Giorgione was, indeed, one of the inspired, unpredictable innovators who disturb the course of history; and in this picture he has illustrated one of the comforting illusions of civilised man, the myth of Arcadia, which had been popularised some twenty years earlier by the poet Sannazaro. Of course, it is only a myth. Country life isn’t at all like this, and even on a picnic ants attack the sandwiches and wasps buzz round the wine glasses. But the pastoral fallacy had inspired Theocritus and Virgil, and had not been unknown in the Middle Ages. Giorgione has seen how fundamentally pagan it is.

True, but I don’t believe that the pastoral fallacy is childish. Pace Arthur Clarke, achieving Arcadia is an essentially psychogenic endeavour rather than a technological one. And I sincerely believe that utopia is feasible: only human primitivism, and especially the “monsters from the Id” currently affecting the white peoples, prevent it.

It has long seemed to me wise thinking about an ideal to direct our efforts toward it. It doesn’t matter if the ideal encounters numerous pitfalls: our will should incessantly be directional toward the worlds of the Florentine Fête. If the will of a sufficiently massive amount of white people is noble, the outside world can and will only represent the nobility of that will. Clark said:

With Giorgione’s picnic the balance and enjoyment of our human faculties seems to achieve perfection. But in history all points of supposed perfection have a hint of menace; and Giorgione himself discovers it in that mysterious picture known as the Tempesta.

What on earth is going on? What is the meaning of this half-naked woman suckling a baby, this flash of lightening, this broken column? Nobody knows; nobody has ever known.

To me the meaning is obvious. Even since the Renaissance artists started to see that the cities, more inclined to Mammon than to Raphael’s square, were places of tribulation in contrast to the madonna and her child with the man standing in contrapposto. Broken pillars often symbolize death (that bucolic world was about to die), and the painting’s storm in the background could be interpreted to symbolize urban turmoil.

By “art” I mean an evolved sense of beauty which is almost completely absent in today’s nationalists. Most of them are quite a product of Jewish modernity whether with their music, lifestyles or Hollywood tastes, to a much greater degree than what they think. For nationalism to succeed an evolved sense of female beauty has to be the starting point to see the divine nature of the white race. In Clark’s own words, “For all these reasons I think it is permissible to associate the cult of ideal love with the ravishing beauty and delicacy that one finds in the madonnas of the thirteenth century. Were there ever more delicate creatures than the ladies on Gothic ivories? How gross, compared to them, are the great beauties of other woman-worshiping epochs.”

By “art” I mean an evolved sense of beauty which is almost completely absent in today’s nationalists. Most of them are quite a product of Jewish modernity whether with their music, lifestyles or Hollywood tastes, to a much greater degree than what they think. For nationalism to succeed an evolved sense of female beauty has to be the starting point to see the divine nature of the white race. In Clark’s own words, “For all these reasons I think it is permissible to associate the cult of ideal love with the ravishing beauty and delicacy that one finds in the madonnas of the thirteenth century. Were there ever more delicate creatures than the ladies on Gothic ivories? How gross, compared to them, are the great beauties of other woman-worshiping epochs.”