This entry should be understood based on what, in Daybreak, I said about Johann Sebastian Bach: that, while I am capable of appreciating the art of the father of classical music in recent centuries, a priest of the sacred words repudiates religious works such as his St Matthew Passion.

Octavio Paz used to say that Dante was the poet of the West par excellence. That’s true only if we refer to Western Christian Civilisation, but not to European Civilisation in general. The matrix created by Christianity so permeated the soul of the common Westerner that even a non-Christian like Paz was able to say what he said about Dante.

I repudiate Dante for the same reason I repudiate Bach: his art is Christian propaganda. And the same can be said of cathedrals, despite their beauty. And the same can be said of the Dante for the English, John Milton. Once one breaks with the paradigm of the day everything seems retarded, and even iniquitous to the mental health of the Aryan man.

Milton’s parents intended him for the church and the young poet grew up in a very puritanical environment. Milton was twenty-one when he created his first masterpiece, an ode to the nativity of Christ. He later rebelled against ideas of free will and predestination, which is why some consider Milton, the contemporary of Hobbes and Kepler, a Renaissance man. I find that claim grotesque (see what I say about Erasmus and the real Renaissance in Daybreak).

Milton travelled to Italy and visited Galileo when the latter was an old man and a prisoner of the Inquisition. Looking through the telescope, young Milton saw for the first time the new conception of space (in the medieval worldview the Moon was believed to be immaculate, incapable of scarring). That did him no good, since years later, in his masterpiece, although he paid homage to his experience with Galileo, Milton was always a slave to his parental introjects by making Satan perform a terrible and daring flight through the cosmos, from the lavas of hell to the new world created by the God of the Jews for Man. In other words, it is the structure of the inner self—how it had been programmed from childhood—that counts, not the facts of the empirical world, pace Galileo. Milton never left the matrix of his time.

Milton travelled to Italy and visited Galileo when the latter was an old man and a prisoner of the Inquisition. Looking through the telescope, young Milton saw for the first time the new conception of space (in the medieval worldview the Moon was believed to be immaculate, incapable of scarring). That did him no good, since years later, in his masterpiece, although he paid homage to his experience with Galileo, Milton was always a slave to his parental introjects by making Satan perform a terrible and daring flight through the cosmos, from the lavas of hell to the new world created by the God of the Jews for Man. In other words, it is the structure of the inner self—how it had been programmed from childhood—that counts, not the facts of the empirical world, pace Galileo. Milton never left the matrix of his time.

In 1649 Charles I of England was beheaded and Milton became the point man for the new regime of Cromwell, who brought the Jews back to the island. But Milton found himself in trouble after the fall of Cromwell, when his body was exhumed and hanged for public shame. To make matters worse, in 1665 he fled London because of the plague, and the great fire of 1666 destroyed the house where his parents had instilled Christian Puritanism in him: his only important property. But Milton had already amalgamated the religious parental introject with his mind.

Twice widowed, after half a century of existence in this world Milton was lucky enough to marry a woman of twenty-four. Returning to London, he published his great poem in 1667 (Paradise Lost is a complete cosmological system!). Two years later, that first edition of thirteen hundred copies was out of print.

Milton, now blind, forced his daughters, Mary and Deborah, to read books to him and dictated his verses to them. The two girls were condemned to a test of patience as they read to their father in foreign languages they didn’t understand. In recent posts, I linked to videos that explain the narcissistic personality. Milton was one of them, and he considered his daughters, to whom he had given biblical names, tools of the trade.

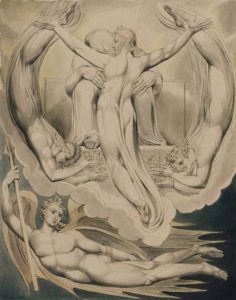

Milton’s masterpiece, his epic poem, Paradise Lost written in blank verse, influenced the generation of English Romantics. William Blake, poet and painter, is considered the most inspired and congenial of Milton’s illustrators. He has a famous drawing in which God the Father embraces God the Son, who has offered himself for Redemption.

If any of my readers did a close reading of my Day of Wrath, he would recall that in the Mesoamerican pantheon, the parent Gods reward the Children Gods who sacrificed themselves by throwing themselves on the stake to become the Sun and the Moon. In that book, my analysis was that the opposite was Zeus, who, instead of submitting to the will of primitive gods (like the Christian god and the Mesoamerican gods), rebelled against the tyrant father, Cronus. If there is one thing that the intellectual sympathisers of American racialism still don’t understand, it is that psychohistorically the Jewish deity represented a regression from the level to which the Aryan had already reached in the Greco-Roman world.

Some notable apostates from Christianity realised this to some extent. In his Candide for example, Voltaire alludes to Milton as a ‘barbarian’, and Ezra Pound branded Paradise Lost as ‘asinine’ sanctimony and beastly Hebraism. I would go further.

In The Fair Race we can read that, if the Aryan is saved from extinction, in the new ecclesias where values are transvalued, young Aryans will be taught Indo-European culture. This obviously excludes the classics of Western Christian Civilisation. The poems of Dante and Milton ultimately reinforce the churches: the opposite of the Indo-European ecclesia that Julian the Apostate, and Hitler, wanted to restore. In the future Aryan state Christian propaganda should be suspended regardless of its aesthetic value.