The following is my abridgement of chapter 18 of William Pierce’s history of the white race, Who We Are:

Christianity Spreads from Levant

to Dying Roman Empire,

then to Conquering Germans

Germans ‘Aryanize’ Christian Myths,

but Racially Destructive Ethics Retained

During the turbulent and eventful fifth century the Germans largely completed their conquest of the West. In the early years of that century German tribesmen, who had been raiding the coast of Roman Britain for many years, began a permanent invasion of the southeastern portion of the island, a development which was eventually to lead to a Germanic Britain.

In 476 Odoacer, an Ostrogothic chieftain who had become a general of Rome’s armies, deposed the last Roman emperor and ruled in his own name as king of Italy. Meanwhile the Visigoths were expanding their holdings in Gaul and completing their conquest of Spain, except for the northwestern region already held by their Suebian cousins and an enclave in the Pyrenees occupied by a remnant of the aboriginal Mediterranean inhabitants of the peninsula, the Basques.

And throughout the latter part of the century the Franks, the Alemanni, and the Burgundians were consolidating their own holds on the former Roman province of Gaul, establishing new kingdoms and laying the basis for the new European civilization of the Middle Ages. Everywhere in the West the old, decaying civilization centered on the Mediterranean gave way to the vigorous White barbarians from the North.

Oriental Infection. But the Germans did not make their conquest of the Roman world without becoming infected by some of the diseases which flourished so unwholesomely in Rome during her last days. Foremost among these was an infection which the Romans themselves had caught during the first century, a consequence of their own conquest of the Levant. It had begun as an offshoot of Judaism, had established itself in Jerusalem and a few other spots in the eastern Mediterranean area, and had traveled to Rome with Jewish merchants and speculators, who had long found that city an attractive center of operations.

It eventually became known to the world as Christianity, but for more than two centuries it festered in the sewers and catacombs of Rome, along with dozens of other alien religious sects from the Levant; its first adherents were Rome’s slaves, a cosmopolitan lot from all the lands conquered by the Romans. It was a religion designed to appeal to slaves: blessed are the poor, the meek, the wretched, the despised, it told them, for you shall inherit the earth from the strong, the brave, the proud, and the mighty; there will be pie in the sky for all believers, and the rest will suffer eternal torment. It appealed directly to a sense of envy and resentment of the weak against the strong.

Edict of Milan. By the end of the third century Christianity had become the most popular as well as the most militant of the Oriental sects flourishing among the largely non-Roman inhabitants of the decaying Roman Empire. Even as late as the first years of the fourth century, under Emperor Diocletian, the Roman government was still making efforts to keep the Christians under control, but in 313 a new emperor, Constantine, decided that, if you can’t lick ’em, join ’em, and he issued an imperial edict legitimizing Christianity.

Although one of Constantine’s successors, Julian, attempted to reverse the continuing Christianization of the Roman Empire a few years later, it was already too late: the Goths, who made up the bulk of Rome’s armies by this time, had caught the infection from one of their own slaves, a Christian captive whom they called Wulfila.

A Romanticized view of Wulfila

explaining the Gospels to the Goths in ca. 310

Wulfila was a tireless and effective missionary, and the Goths were an uprooted and unsettled people, among whom the new religion took hold easily. Wulfila’s translation of the Bible into Gothic greatly speeded up the process.

Conversion of the Franks. Before the end of the fourth century Christianity had also spread to the Vandals, Burgundians, Lombards, Gepids, and several other German tribes. A little over a century later the powerful nation of the Franks was converted. By the beginning of the second quarter of the sixth century, the only non-Christian Whites left were the Bavarians, Thuringians, Saxons, Frisians, Danes, Swedes, and Norse among the Germans—and virtually all the Balts and Slavs.

One can only understand the rapid spread of Christianity during the fourth and fifth centuries by realizing that, for all practical purposes, it had no opposition. That is, there was no other organized, militant, proselytizing church competing effectively with the Christian church.

Athanaric the Goth. The Christians had many individual opponents, of course: among the Romans several of the more responsible and civic-minded emperors, such as Diocletian, as well as what was left of the tradition-minded aristocracy; and among the Germans many farsighted leaders who resisted the imposition of an alien creed on their people and the abandonment of their ancient traditions. Athanaric, the great Gothic chieftain who led his people across the Danube in 376 to save them from the invading Huns, was notable in this regard.

Athanaric and the other traditionalists failed to halt the spread of Christianity, because they were only individuals. Although there were pagan priests, the traditional German religion never really had a church associated with it. It consisted in a body of beliefs, tales, and practices passed from generation to generation, but it had no centralized organization like Christianity.

Folk-religion. German religion was a folk-religion, which grew organically out of the people and out of the land they occupied. The boundary between a tribe’s most ancient historical legends and its religious myths, between its long-dead heroes and chieftains and its gods, was blurred at best. Because German religion belonged to the people and the land, it was not a proselytizing religion; the German attitude was that other peoples and races likewise had their own folk-religions, and it would be unnatural to impose one race’s religion on another race.

And because German religion was rooted in the land as well as in the people, it lost some of its viability when the people were uprooted from their land. It is no coincidence that the conversions of the Goths, Vandals, Burgundians, Lombards, Franks, and many other German tribes took place during the Voelkerwanderung, a period of strife, disorientation, and misery for many of those involved: a period when whole nations lost not only their ancient homelands but also their very identities.

Fire and Sword. After the Voelkerwanderung ended in the sixth century, the Christianization of the remaining pagan peoples of Europe proceeded much more slowly—and generally by fire and sword rather than by peaceful missionary effort. Whereas the Franks had become Christians more or less painlessly when their king Clovis (Chlodweg) converted for political reasons at the end of the fifth century, it was another 300 years before the Frankish king Charlemagne (Karl the Great) was able to bring about the conversion of his Saxon neighbors, and he accomplished that only by butchering half of them in a series of genocidal wars.

Early Christianity, in contrast to German religion, was as utterly intolerant as the Judaism from which it sprang. Even Roman religion, which, as an official state religion, equated religious observance with patriotism, tolerated the existence of other sects, so long as they did not threaten the state. But the early Christians were inspired by a fanatical hatred of all opposing creeds.

Also in contrast to German and Roman religion, Christianity, despite its specifically Jewish roots, claimed to be a universal (i.e., “catholic”) creed, equally applicable to Germans, Romans, Jews, Huns, and Negroes.

“Every place… shall be yours.” The Christians took the Jewish tribal god Yahweh, or Jehovah, and universalized him. Originally he seems to have been a deity associated with one of the dormant volcanoes of the Arabian peninsula, a god so distinctly Semitic that he had a binding business contract (“covenant”) with his followers: if the Jews would remain faithful and obedient to him, he would deliver all the wealth of the non-Jewish peoples of the world into their hands. Observant Jews even today remind themselves of this by fastening mezuzoth to the door frames of their homes, wherein the verses from their Torah spelling out the Jews’ side of their larcenous deal with Yahweh are inscribed (Deuteronomy 6:4-9, 11:13-21; Yahweh’s reciprocal obligations are in the verses immediately following).

Nevertheless, the early Christian church, armed with an effective organization and a proselytizing fervor, and armored with a supreme contempt for everything non-Christian, was able to supplant Jupiter and Wotan alike with Yahweh.

The Germans, however, recreated the Semitic Yahweh in the image of their own Wotan, even as they accepted the new faith. The entire Christian ritual and doctrine, in fact, were to a large extent “Aryanized” by the Germans to suit their own inner nature and lifestyle. They played down the slave-religion aspects of Christianity (“the meek shall inherit the earth”) and emphasized the aspects which appealed to them (“I come bearing not peace, but a sword”). The incoherence and the multitude of internal inconsistencies of the doctrine made this sort of eclecticism easy.

Yule, Easter, Harvest Festival. In general, the Germans accepted without difficulty the Christian rituals—especially those which, like Christmas, Easter, and Thanksgiving were deliberately redesigned to correspond to pagan rituals and festivals of long standing—and the myths (parthenogenesis, turning water into wine, curing the blind, resurrection from the dead, etc.), and they ignored the ethics (turn the other cheek, all men are brothers, etc.).

A Frank of the seventh or eighth century would tremble in superstitious awe before some fragment of bone or vial of dried blood which the Church had declared a sacred relic with miracle-working powers—but if you smote him on the cheek you would have a fight on your hands, not another cheek turned.

As for the brotherhood of man and equality in the eyes of the Lord, the Germans had no time for such nonsense; when confronted with non-Whites, they instinctively reached for the nearest lethal weapon. They made mincemeat out of the Avars, who were cousins to the Huns, in the seventh century, and the Christianized Franks or Goths of that era would know exactly what to do with a few hundred thousand rioting American Blacks; they would, in fact, positively relish the opportunity to do what needed doing.

It could not have been expected to be otherwise. In the first place, a totally alien religion cannot be imposed on a spiritually healthy people—and the Germans were still essentially healthy, despite the dislocations caused by the Voelkerwanderung. Christianity had to be modified to suit their nature—at least, temporarily. In the second place, the average German did not have to come to grips with the alien moral imperatives of the Sermon on the Mount. All he had to do was learn when to genuflect; wrestling with Holy Writ was exclusively the problem of the clergy.

It was not until the Reformation, in the sixteenth century, that the laity began studying the Bible and thinking seriously about its contents. Even then, however, the tendency was to interpret alien teachings in a way that left them more or less compatible with natural tendencies.

Slave Morality. But Christian ethics—the slave morality preached in the Roman catacombs—was like a time bomb ticking away in Europe: a Trojan horse brought inside the fortress, waiting for its season. That season came, and the damage was done. Today Christianity is one of the most active forces working from within to destroy the White race.

From the Christian churches came the notion of “the White man’s burden,” along with the missionaries who saw in every African cannibal or Chinese coolie a soul to be saved, of equal value in the eyes of Jehovah to any White soul. It is entirely a Christian impulse—at least, on the part of the average American voter, if not the government—which sends American food and medical supplies to keep alive swarming millions of Asiatics, Africans, and Latins every time they have a famine, so that they can continue to outbreed Whites.

The otherworldly emphasis on individual salvation, on an individual relationship between Creator and creature which relegates the relationship between individual and race, tribe, and community to insignificance; the inversion of natural values inherent in the exalting of the botched, the unclean, and the poor in spirit in the Sermon on the Mount—the injunction to “resist not evil”—all are prescriptions for racial suicide. Indeed, had a fiendishly clever enemy set out to concoct a set of doctrines intended to lead the White race to its destruction, he could hardly have done better.

The “White guilt” syndrome exploited so assiduously by America’s non-White minorities is a product of Christian teachings, as is the perverse reverence for “God’s chosen people” which has paralyzed so many Christians’ wills to resist Jewish depredations.

Moses Replaces Hermann. Not the least of the damage done by the Christianization of Europe was the gradual replacement of White tradition, legend, and imagery by that of the Jews. Instead of specifically Celtic or German or Slavic heroes, the Church’s saints, many of them Levantines, were held up to the young for emulation; instead of the feats of Hermann or Vercingetorix, children were taught of the doings of Moses and David.

Europeans’ artistic inspiration was turned away from the depiction of their own rich heritage and used to glorify that of an alien race; Semitic proverbs and figures of speech took precedence over those of Indo-European provenance; Europeans even abandoned the names of their ancestors and began giving Jewish names to their children: Samuel and Sarah, John and Joan, Michael and Mary, Daniel and Deborah.

Despite all these long-term consequences of Christianity, however, the immediate symptoms of the infection which the conquering Germans picked up from the defeated Romans were hardly noticeable; White morals and manners, motivations and behavior remained much as they had been, for they were rooted in the genes—but now they had a new rationale.

Today’s Christian Patriots. And it is only fair to note that even today a fairly substantial minority of White men and women who still think of themselves as Christians have not allowed their sounder instincts to be corrupted by doctrines suited to a following of mongrelized slaves. They ignore the Jewish origins of Christianity and justify their instinctive dislike and distrust of Jews with the fact that the Jews, in demanding that Jesus be killed, became a race forever accursed (“His blood be on us and on our children”).

They interpret the divine injunction of brotherhood as applying only to Whites. Like the Franks of the Middle Ages, they believe what suits them and conveniently forget or invent their own interpretation for the rest. Were they the Christian mainstream today, the religion would not be the racial menace that it is. Unfortunately, however, they are not; virtually none are actively affiliated with any of the larger, established Christian churches.

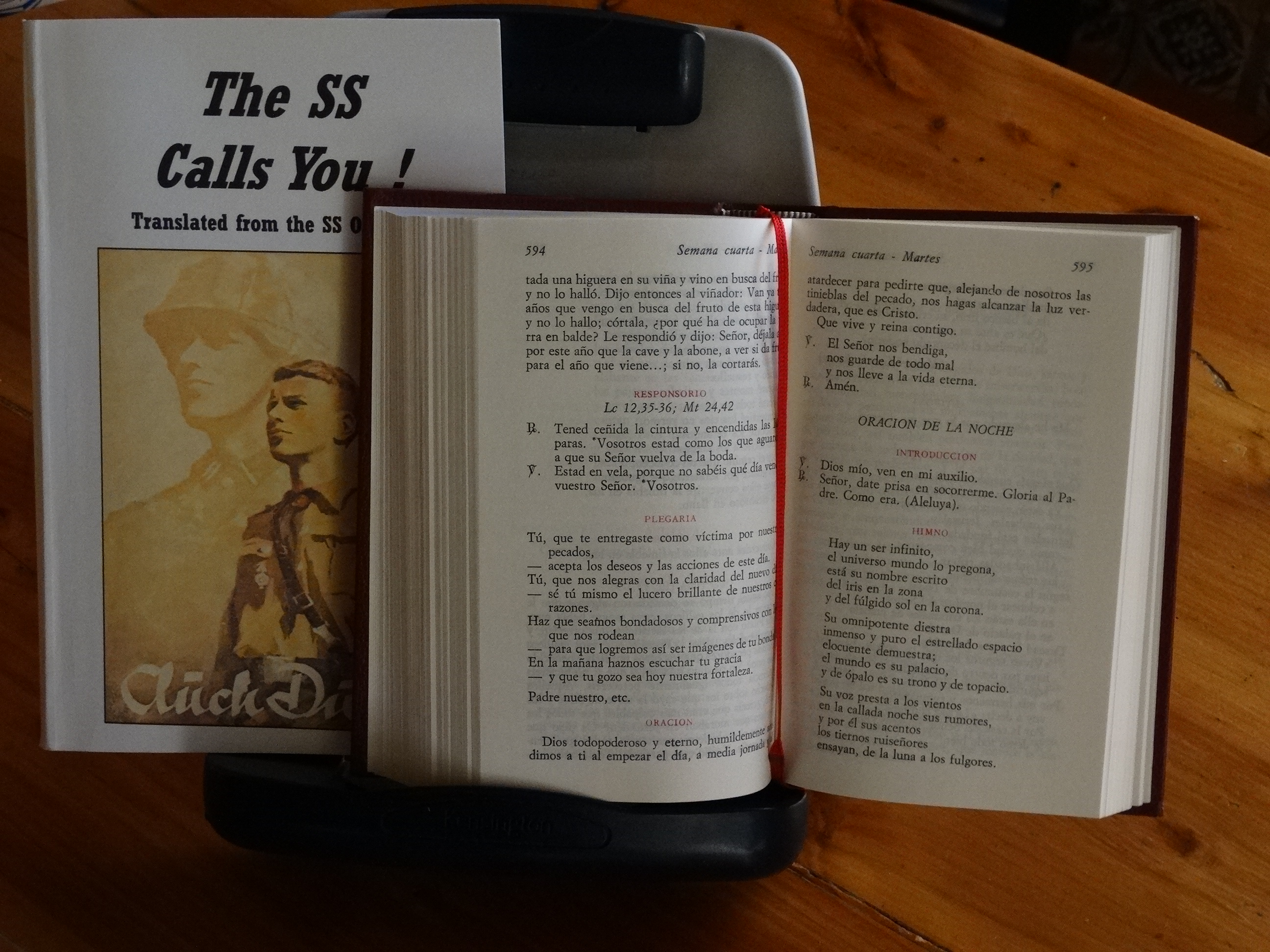

Perhaps it is worth closing this post with an image of how the Roman church bewitches its faithful precisely with super-aesthetic editions of its liturgy: the most aesthetic editions I have ever seen in a publishing house! If with money it is possible to publish this kind of little books to instil evil, won’t it be possible to found a new publishing house that collects all these little jewels of the Third Reich in editions as elegant as those of Ediciones Cristiandad, whose publishing house resides in Madrid?

Perhaps it is worth closing this post with an image of how the Roman church bewitches its faithful precisely with super-aesthetic editions of its liturgy: the most aesthetic editions I have ever seen in a publishing house! If with money it is possible to publish this kind of little books to instil evil, won’t it be possible to found a new publishing house that collects all these little jewels of the Third Reich in editions as elegant as those of Ediciones Cristiandad, whose publishing house resides in Madrid?