“There is no human as willfully, malignantly, and self-destructively stupid as a White person in the throes of a moral panic.”

After summarizing the Jewish problem in the foreword to Tomislav Sunić’s Homo Americanus, Kevin MacDonald wrote:

But the other side of the equation must also be examined—the traits that predispose Westerners to willingly accept their own oblivion as a moral necessity. Here Sunić emphasizes the heritage of Christian universalism and, especially, in the case of America, the heritage of Puritan moralism. [page xxxiii]

However, for most white nationalists it is unthinkable that the primary cause of our woes is White pathology—Judeo-Christianity and its secular version of egalitarianism—, not the Jewish problem, which according to Sunić is only a secondary infection.

Below I’ve typed directly from my copy of Homo Americanus: Child of the Postmodern Age, published in 2007. In the third chapter, “The origins of political correctness and America’s role in its perfection,” Sunić wrote:

“Political correctness” is a euphemism for intellectual censorship whose legal and cultural origins can be traced to America and Europe, immediately after the Second World War. For the first time in European history, a large scale attempt was made by the victorious United States of America, the Soviet Union and their allies, to condemn a large number of thinkers and writers from defeated Germany and its allies to intellectual oblivion… Any criticism—however mild it may be—of egalitarianism and multiculturalism can earn the author or politician the stigma of “fascism,” or even worse, of “anti-Semitism”… How did this happen and who introduced this climate of intellectual censorship and self-censorship in America and Europe at the beginning of the third millennium?

Brainwashing the Germans

In the aftermath of World War II, the role of the American-based Frankfurt School scholars and European Marxist intellectuals was decisive in shaping the new European cultural scene. Scores of American left-leaning psychoanalysts—under the auspices of the Truman government—swarmed over Germany in an attempt to rectify not just the German mind but also change the brains of all Europeans. Frankfurt School activists were mostly of German-Jewish extraction who had been expelled by the German authorities during National Socialist rule and who, after the Second World War, came back to Europe and began laying the foundations for a new approach in the study of humanities.

But there were also a considerable number of WASP Puritan-minded scholars and military men active in post-war Germany, such as Major General McClure, the poet Archibald MacLeish, the political scientist Harold Laswell, the jurist Robert Jackson and the philosopher John Dewey, who had envisaged copying the American way of democracy into the European public scene. They thought of themselves as divinely chosen people called to preach American democracy—a procedure which would be used by American elites in the decades to come of each occasion and in every spot of the world. It never crossed the mind of American post-war educators that their actions would facilitate the rise of Marxist cultural hegemony in Europe and lead to the prolongation of the Cold War.

As a result of Frankfurt School reeducational endeavors in Germany, thousands of book titles in the fields of genetics and anthropology were removed from library shelves and thousands of museum artifacts were, if not destroyed in the preceding Allied fire bombing, shipped to the USA and the Soviet Union. The liberal and communist tenets of free speech and freedom of expression did not apply at all to the defeated side which had earlier been branded as “the enemy of humanity.”

Particularly harsh was the Allied treatment of German teachers and academics. Since National Socialist Germany had significant support among German teachers and university professors, it was to be expected that the US reeducational authorities would start screening German intellectuals, writers, journalists and film makers. Having destroyed dozens of major libraries in Germany, with millions of volumes gone up in flames, the American occupying powers resorted to improvising measures in order to give some semblance of normalcy in what later became “the democratic Germany.” The occupying powers realized that universities and other places of higher learning could always turn into centers of civil unrest, and therefore, their attempts at denazification were first focused on German teachers and academics…

Among the new American educators, the opinion prevailed that the allegedly repressive European family was the breeding ground of political neurosis, xenophobia, and racism among young children… Therefore, in the eyes of the American reeducational authorities, the old fashioned European family needed to be removed and with it some of its Christian trappings. Similar antifascist approaches to cultural purges were in full swing in Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe, but as subsequent events showed, the Western version of political correctness proved to be far more effective.

In the early postwar years the Americans and their war allies carried out large scale intellectual purges in the media, notably with issuing special licenses to newly launched newspaper outlets in Germany. The words “Nazism” and “Fascism” gradually lost their original meaning and turned, instead, into synonyms of evil. The new educational principle of reduction ad hitlerum became a new paradigm for studying social sciences. A scholar who would slightly diverge from these newly installed antifascist pedagogical methods would have meager chances for career advancement if not outright fired. In some cases, even sixty years after the end of World War II, he would have to face stiff penalties, including jail term. During the same postwar period in communist Eastern Europe, Soviet-led cultural repression was far more severe, but, ironically, its vulgar transparency, as seen in previous chapters, gave its victims an aura of martyrdom…

The ideology of antifascism became by the late 20th century a form of negative legitimacy for the entire West… Western European political elites went a step further; in order to show to their American sponsors democratic credentials and their philo-Semitic attitudes, they introduced strict legislation forbidding historical revisionism of the Second World War and any critical study of mass immigration into Western Europe…

At the beginning of the 21st century, the whole intellectual climate in America and especially in Europe came to resemble the medieval period by forbidding critical inquiry into “self-evident truths”… The German Criminal Code appears in substance more repressive than the former Soviet Criminal Code… Day after day Germany has to prove that it can perform self-educational tasks better than its American tutor. It must show signs of being the most servile disciple of the American hegemon, given that the “transformation of the German mind (was) the main home work of the military regime.” If one wishes to grasp the concept of modern political correctness, one must study in detail the political psychology of the traumatized German people…

Given that all signs of nationalism, let alone racialism, are reprimanded in Germany… it is considered legally desirable to hunt down European heretics… Germany, along with other European countries, has now evolved into a “secular theocracy”… Similar to Communism, historical truth in Western Europe is not established by an open academic debate but by state legislation… The entire West, including America itself, has become a victim of collective guilt… Thus the ruling class in America and Europe successfully resorts to the scarecrow of debate stopping words, such as “anti-Semitism” and “Neo-Nazism,” as an alibi for legitimizing its perpetual status quo.

The specter of a projected catastrophic scenario must silence all free spirits. Naturally, if fascism is legally decreed as absolute evil, any aberration in the liberal system will automatically appear as a lesser evil. The modern liberal system, which originated in America, functions as a self-perpetuating machine of total mind control.

The proportion of writers and journalists who were shot, imprisoned, and barred from their profession surpasses all other professional categories. Do we need to be reminded of the assassination of Albert Clément, Philippe Henriot, Robert Denoël, of the suicide of Drieu La Rochelle, of the death of Paul Allard in prison prior to court hearings and of the executions of Georges Suarez, Robert Brasillach, Jean Luchaire… the death sentence pronounced in absentia or a commuted prison sentence for Lucien Rebatet, Pierre-Antoine Cousteau, etc.? The targets were the providers of the ideas more than the entrepreneurs who had contributed to the German war industry. By 1944 the professional interdiction by the CNE (Comité nationale des écrivains) targeted approximately 160 journalists and writers. [Dominique Venner, Historie de la Collaboration (Paris: Pygmalion, 2000), pp. 515-516]

After the Second World War, an ex post facto law was adopted in France, making some political opinions a crime… The defendants are not blamed for their acts—provided there were any—but for their ideas. At the beginning of the 21st century, as a result of this repressive intellectual climate of Europe, hundreds of French and German authors showing sympathies for anti-liberal authors or who voice criticism of multicultural experiments in postmodern Europe or America are subject to legal sanctions and public ostracism…

It is true that Western Europe, unlike Eastern Europe, could escape the naked terror of communism, although Western Europe’s own subspecies, the antifascist homunculi, as German scholar Günther Maschke derogatorily calls modern Americanized opinion makers in Europe, tirelessly watch for any sign of nationalist revival… One wonders, why does not the Communist criminal legacy trigger a similar negative outcry in the wider public as the fascist legacy? Why must the public stay tuned to endless recitals of National Socialist crimes, whereas rarely ever does it have an opportunity to hear something about Communist horrors?…

The larger public in America and Europe have little knowledge that in Germany alone, in the last decade of the 20th century, thousands of individuals, ranging from German youngsters cracking jokes about non-European immigrants, to scholars dealing critically with the Jewish Holocaust, have been sentenced to either fines or to considerable prison terms. In the political and academic environment, writes the modern German heretic Germar Rudolf, it must, therefore, not come as a surprise that “political scientists, sociologists and historians do not wish to call things by their names”…

The spiral of intellectual cowardice only reinforces the Americanized system’s thought control. The silence of American academics and prominent human rights advocates, following the arrest of Rudolf in America, proves time and again that American intellectuals realize that there must be limits to their freedom of speech… The American brain child, the post-war Federal Republic of Germany, might enter some day into history books as the most bizarre system ever seen in Europe.

Chapter IV: The Biblical origins of American fundamentalism

America is a land of the Bible. In America, it is virtually unheard of to openly declare oneself an agnostic or an atheist and to aspire at the same time to some high political office. No country on earth has ever known such a high degree of Biblical influence as the United States of America…

The legacy of Biblical Puritanism lost its original theological God-fearing message and adopted, at the turn of the 20th century, a secular neo-liberal form of the human rights gospel. Subsequently, by a bizarre twist of fate, the Calvinist legacy of Puritanism that had been chased from Europe by the end of the 17th century started its journey back home to Europe—particularly after America came out victorious after the Second World War. Although Europe remains a much less Bible-oriented society than America, the moralistic message, as an old Bible derivative, is making strong headways in the postmodern European social arena. However much the surface of America shows everywhere signs of secularism, rejecting the Christian dogma and diverse religious paraphernalia, in the background of American political thought always looms the mark of the Bible.

In hindsight, the British context of the 17th century, the strongest political standard bearer of Puritanism, Oliver Cromwell, appears as a passing figure who did not leave a lasting political impact on the future of the United Kingdom or on the rest of continental Europe. Yet Cromwell’s unwitting political legacy had more influence on the American mindset than Lenin’s rhetoric did on the future of communized Russia…

In contrast to European Catholicism and Lutheranism, Calvinist Puritanism managed to strip Christianity of pagan elements regarding the transcendental and the sacred, and reduced the Christian message solely to the basic ethical precepts of good behavior. American Puritanism deprived Christianity of its aesthetic connotations and symbolism, thereby alienating American Christians as well as American cultural life in general, further from its European origins. In this way, Americans became ripe for modernism in architecture and new approaches in social science… This hypertrophy of moralism had its birth place in New England during the early reign of the Pilgrim fathers, which only proves our thesis that New England and not Washington D.C. was the birth place of Americanism…

It was to be expected with the Puritans’ idea of self-chosenness that Americans took a special delight in the Old Testament. From it, almost exclusively, they drew their texts, and it never failed to provide them with justification for their most inhuman and bloodthirsty acts. Their God was the God of the Old Testament; their laws were the laws of the Old Testament. Their Sabbath was Jewish, not Christian…

“Judeo-American” monotheism

American founding myths drew their inspiration from Hebrew thought. The notion of the “City on the Hill” and “God’s own country” were borrowed from the Old Testament and the Jewish people… Of all Christian denominations, Calvinism was the closest to the Jewish religion and as some authors have noted, the United States owes its very existence to the Jews. “For what we call Americanism,” writes Werner Sombart, “is nothing else than the Jewish spirit distilled.” Sombart further writes that “the United States is filled to the brain with the Jewish spirit”…

Very early on America’s founding fathers, pioneers, and politicians identified themselves as Jews who had come to the new American Canaan from the pestilence of Europe. In a postmodern Freudian twist, these pilgrims and these new American pioneers were obliged to kill their European fathers [the Germans] in order to facilitate the spreading of American democracy world-wide. “Heaven has placed our country in this situation to try us; to see whether we would faithfully use the incalculable power in our hands for spreading forward the world’s regeneration”…

Does that, therefore, mean that our proverbial Homo americanus is a universal carbon copy of Homo judaicus? The word “anti-Semite” will likely be studied one day as a telling example of postmodern political discourse, i.e. as a signifier for somebody who advocates the reign of demonology… How does one dare critically talk about the predominance of the Judeo-American spirit in America without running the risk of social opprobrium or of landing into psychiatric asylum, as Ezra Pound once did?…

Eventually, both American Jews and American Gentiles will be pitted into an ugly clash from which there will be no escape for any of them… It is the lack of open discussion about the topic of the Jews that confirms how Jews play a crucial role in American conscience building, and by extension, in the entire West… But contrary to classical anti-Semitic arguments, strong Jewish influence in America is not only the product of Jews; it is the logical result of Gentiles’ acceptance of the Jewish founding myths that have seeped over centuries into Europe and America in their diverse Christian modalities. Postmodern Americanism is just the latest secular version of the Judean mindset… Blaming American Jews for extraterrestrial powers and their purported conspiracy to subvert gentile culture borders on delusion and only reflects the absence of dialogue…

One can naturally concur that Americans are influenced by Jews, but then the question arises as to how did it happen?… Jews in America did not drop from the moon. Jewish social prominence, both in Europe and America, has been the direct result of the white Gentile’s acceptance of Jewish apostles—an event which was brought to its perfection in America by early Puritan Pilgrim Founding Fathers. Be it in Europe or in the USA, Christian religious denominations are differentiated versions of Jewish monotheism. Therefore, the whole history of philo-Semitism, or anti-Semitism in America and in Europe, verges on serious social neurosis.

American pro-Jewish or “Jewified” intellectuals often show signs of being more Jewish than Jews themselves… As the latest version of Christianized and secularized monotheism, Judeo-Americanism represents the most radical departure from the ancient European pre-Christian genius loci… Christian anti-Semites in America often forget, in their endless lamentation about the changing racial structure of America, that Christianity is by definition a universal religion aiming to achieve a pan-racial system of governance. Therefore, Christians, regardless whether they are hypermoralistic Puritans or more authority prone Catholics, are in no position to found an ethnically and racially all white Gentile society while adhering at the same time to the Christian dogma of pan-racial universalism…

The West, and particularly America, will cease to be Israelite once it leaves this neurosis, once it returns to its own local myths… Many Jewish scholars rightly acknowledge deep theological links between Americanism and Judaism. Also, American traditionalists and conservatives are correct in denouncing secular myths, such as Freudism, Marxism, and neo-liberalism which they see as ideologies concocted by Jewish and pro-Jewish thinkers. They fail to go a step further and examine the Judaic origins of Christianity and mutual proximity of these two monotheist religions that make up the foundations of the modern West. Only within the framework of Judeo-Christianity can one understand modern democratic aberrations and the proliferation of new civic religions in postmodernity…

Also, the reason America has been so protective of the state of Israel has little to do with America’s geopolitical security. Rather, Israel is an archetype and a pseudo-spiritual receptacle of American ideology and its Puritan founding fathers. Israel must function as America’s democratic Super-Ego…

Modern individuals who reject Jewish influence in America often forget that much of their neurosis would disappear if their Biblical fundamentalism was abandoned. One may contend that the rejection of monotheism does not imply a return to the worship of ancient Indo-European deities or the veneration of some exotic gods and goddesses. It means forging another civilization, or rather, a modernized version of scientific and cultural Hellenism, considered once as a common receptacle of all European peoples…

In short, Judeo-Christian universalism, practiced in America with its various multicultural and secular offshoots, set the stage for the rise of postmodern egalitarian aberrations and the complete promiscuity of all values. That Americanism can also be a fanatical and intolerant system “without God,” is quite obvious. This system, nonetheless, is the inheritor of a Christian thought in the sense in which Carl Schmitt demonstrated that the majority of modern political principles are secularized theological principles…

America is bound to become more and more a racial pluriverse… Guilt feelings inspired in the Bible, along with the belief in economic progress and the system of big business, pushed America onto a different historical path of no return…

Undoubtedly, many American atheists and agnostics also admit that in the realm of ethics all men and women of the world are the children of Abraham. Indeed even the bolder ones who somewhat self-righteously claim to have rejected Christian or Jewish theologies, and who claim to have replaced them with “secular humanism,” frequently ignore the fact that their self-styled secular beliefs are also grounded in Judeo-Christian ethics. Abraham, Jesus and Moses may be dethroned today, but their moral edicts and spiritual ordinances are much alive in American foreign policy. “The pathologies of the modern world are genuine, albeit illegitimate daughters of Christian theology,” writes De Benoist…

Who can dispute the fact that Athens was the homeland of European America before Jerusalem became its painful edifice?

Chapter V: In Yahweh we trust: A divine foreign policy

It was largely the Biblical message which stood as the origin of America’s endeavor to “make the world safe for democracy.” Contrary to many European observers critical of America, American military interventions have never had as a sole objective economic imperialism but rather the desire to spread American democracy around the world…

American involvement in Europe during World War II and the later occupation of Germany were motivated by America’s self-appointed do-gooding efforts and the belief that Evil in its fascist form had to be removed, whatever the costs might be. Clearly, Hitler declared war on “neutral” America, but Germany’s act of belligerence against America needs to be put into perspective. An objective scholar must examine America’s previous illegal supplying of war material to the Soviet Union and Great Britain. Equally illegal under international law was America’s engaging German submarines in the Atlantic prior to the German declaration of war, which was accompanied by incessant anti-German media hectoring by American Jews—a strategy carried out in the name of a divine mission of “making the world safe for democracy.”

“The crisis of Americanism in our epoch,” wrote a German scholar, Giselher Wirsing, who had close ties with propaganda officials in the Third Reich, “falls short of degeneracy of the Puritan mindset. In degenerated Puritanism lies, side by side with Judaism, America’s inborn danger”…

A war crime of the Bible

In the first half of the 20th century American Biblical fundamentalism resulted in military behavior that American postmodern elites are not very fond of discussing in a public forum. It is common place in American academia and the film industry to criticize National Socialism for its real or alleged terror. But the American way of conducting World War II—under the guise of democracy and world peace—was just as violent if not even worse.

Puritanism had given birth to a distinctive type of American fanaticism which does not have parallels anywhere else in the world. Just as in 17th century England, Cromwell was persuaded that he had been sent by God Almighty to purge England of its enemies; so did his American liberal successors by the end of the 20th century think themselves elected in order to impose their own code of military and political conduct in both domestic and foreign affairs. M.E. Bradford notes that this type of Puritan self-righteousness could be easily observed from Monroe to Lincoln and Lincoln’s lieutenants Sherman and Grant…

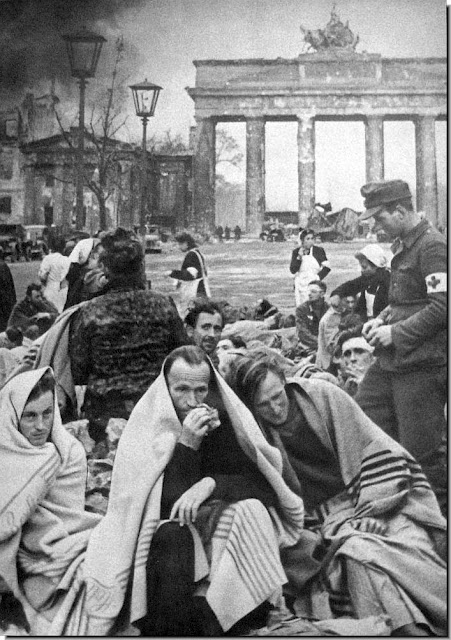

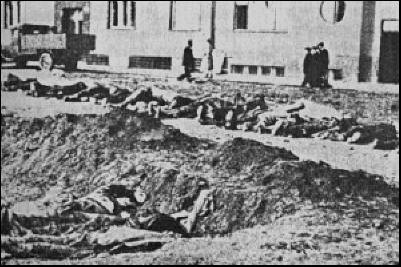

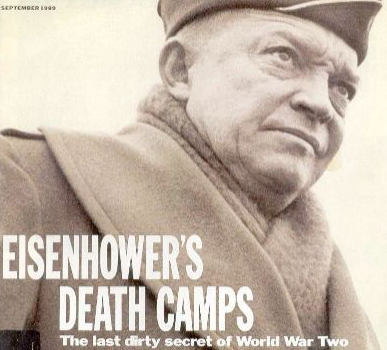

Whereas everybody in American and European postmodern political establishment are obliged to know by heart the body count of Fascist and National Socialist victims, nobody still knows the exact number of Germans killed by American forces during and after World War II. Worse, as noted earlier, a different perspective in describing the US post-war foreign policy toward Europe and Germany is not considered politically correct… [in spite of the fact that] the American mistreatment of German POWs and civilians during World War II must have been far worse than that on Iraq after 2003.

Just as communism, following the Second World War, used large scale terror in the implementation of its foreign policy goals in Eastern Europe, so did America use its own type of repression to silence heretics in the occupied parts of postwar Europe… The American crusade to extirpate evil was felt by Germans in full force in the aftermath of World War II. Freda Utley, an English-American writer depicts graphically in her books the barbaric methods applied by American military authorities against German civilians and prisoners in war ravaged Germany. Although Utley enjoyed popularity among American conservatives, her name and her works fell quickly into oblivion…

In hindsight one wonders whether there was any substantive difference between warmongering Americanism and Communism? If one takes into account the behavior of American military authorities in Germany after World War II, it becomes clear why American elites, half a century later, were unwilling to initiate a process of decommunisation in Eastern Europe,  as well as the process of demarxisation in American and European higher education. After all, were not Roosevelt and Stalin war time allies? Were not American and Soviet soldiers fighting the same “Nazi evil”?

as well as the process of demarxisation in American and European higher education. After all, were not Roosevelt and Stalin war time allies? Were not American and Soviet soldiers fighting the same “Nazi evil”?

It was the inhumane behavior of the American military interrogators that left deep scars on the German psyche and which explains why Germans, and by extension all Europeans, act today in foreign affairs like scared lackeys of American geopolitical interests…

A whole fleet of aircraft was used by General Eisenhower to bring journalists, Congressmen, and churchmen to see the concentration camps; the idea being that the sight of Hitler’s starved victims would obliterate consciousness of our own guilt. Certainly it worked out that way. No American newspaper of large circulation in those days wrote up the horror of our bombing or described the ghastly conditions in which the survivors were living in the corpse-filled ruins. American readers sipped their fill only of German atrocities. [Freda Utley, The High Cost of Vengeance (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co. 1949), p. 183]

Utley’s work is today unknown in American higher education although her prose constitutes a valuable document in studying the crusading and inquisitorial character of Americanism in Europe.

There are legions of similar revisionist books on the topic describing the plight of Germans and Europeans after the Second World War, but due to academic silence and self-censorship of many scholars, these books do not reach mainstream political and academic circles. Moreover, both American and European historians still seem to be light years away from historicizing contemporary history and its aftermath. This is understandable, in view of the fact that acting and writing otherwise would throw an ugly light on crimes committed by the Americans in Germany during and after the second World War and would substantially ruin antifascist victimology, including the Holocaust narrative.

American crimes in Europe, committed in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, included extra-killings of countless German civilians and disarmed soldiers, while tacitly approving serial Soviet genocides and mass expulsions of the German civilian population in Eastern Europe… As years and decades went by, crimes committed by the Americans against the Germans were either whitewashed or ascribed to the defeated Germans…

The exact number of German causalities during and after the Second World War remains unknown. The number of German dead varies wildly, ranging from 6 to 16 million Germans, including civilians and soldiers… It is only the fascist criminology of World War II, along with the rhetorical projection of the evil side of the Holocaust that modern historiographers like to repeat, with Jewish American historians and commentators being at the helm of this narrative. Other victimhoods and other victimologies, notably those people who suffered under communism, are rarely mentioned… According to some German historians over a million and a half of German soldiers died after the end of hostilities in American and Soviet-run prison camps…

The masters of discourse in postmodern America have powerful means to decide the meaning of historical truth and provide the meaning with their own historical context. Mentioning extensively Germany’s war loses runs the risk of eclipsing the scope of Jewish war loses, which makes many Jewish intellectuals exceedingly nervous. Every nation likes to see its own sacred victimhood on the top of the list of global suffering. Moreover, if critical revisionist literature were ever to gain a mainstream foothold in America and Europe, it would render a serious blow to the ideology of Americanism and would dramatically change the course of history in the coming decades.