by Manu Rodríguez

Translated from Spanish

The Messianic Jewish universalism, the democratic, socialist or social and political ideals, have ended up by reducing to a minimum our identity and our bio-symbolic pride and ethnicity. The Aryan nation (Aryans aware of themselves) is now a minimum percentage of its potential population (all white peoples).

The trans-national, trans-racial, trans-cultural ideal that these ideologies preach us (beyond peoples, races, cultures), and that are the staple food in our schools, our media, our mass culture, our universities, our streets, have managed to finally affect us. There are hundreds of years of the same. Please note that the Jewish Messianism has been spreading its venomous message for almost two thousand years. The communist and democratic universalism are a thing of recent times, but have only come to reinforce the old narrative. These two are the same ideals.

Such ideals (such teachings, such ubiquitous messages), after hundreds of years have achieved their purposes: transforming wolves and bears into kids and lambs. We, our peoples, have become weak, insecure, and timid creatures.

All this comes to mind after some news from Norway, outlined in Gates of Vienna and reviewed by Kevin MacDonald at The Occidental Observer in recent days. It is about a situation where the Norwegians are trapped in neighborhoods or areas with a high number of Asian and African-Muslim population. The starting point is a report on the schools. Apparently Norwegian pupils (boys and girls) are in the minority and are constantly insulted or assaulted by the allochthonous young Muslims. This outrageous state of affairs has generated, apparently, more than individual survival strategies.

It must be noted that this is not happening only in Norway but in France, Germany, England… Clearly these foreigners do not esteem us, nor respect us or fear us. In any of our nations they find nothing but isolated and helpless individuals who can be insulted and attacked with impunity. No one will come to their defense. There will be no response, no retaliation.

Why this lack of response, this silence and resignation? We cannot find, at the individual level (in the cited cases), any valor or pride or self-respect. There is no one to confront them. All seek to escape. That this has happened to the descendants of the fierce and proud Vikings makes one wonder.

Helplessness, weakness, cowardice. This is the result of our upbringing and instruction in the last hundreds of years in the hands of priests of foreign divinities and their universalist and altruistic creeds: a hideous transformation.

MacDonald is right in alluding that individualism and the atomization of white societies and lack of support, is where whites find themselves when they are beaten, intimidated, or violated by foreign groups (Asian Muslims, Africans and others). But such individualism and atomization are just symptoms. Symptoms of a people destroyed, annihilated; of a multitude of uprooted, scattered, isolated, weakened, and lost individuals.

The group conscience among us whites in Europe must be strengthened, yes, and in the Magna Europe. But from where, from which basis or fundamentals? What words, what concepts, what symbolic space will keep us together into a one? On which field will we make roots? What is the best soil?

Group conscience has to include race and culture, which is to say, body and soul. We have been so long away from home (since the Christianization), and with so contrary winds, that we have lost the path, the way, the memory. We’ll have to start from the beginning. We have to ask ourselves who we are, where we come from, and where we are going. We need to reclaim the memory, our memory: a collective self-gnosis of the Aryan peoples.

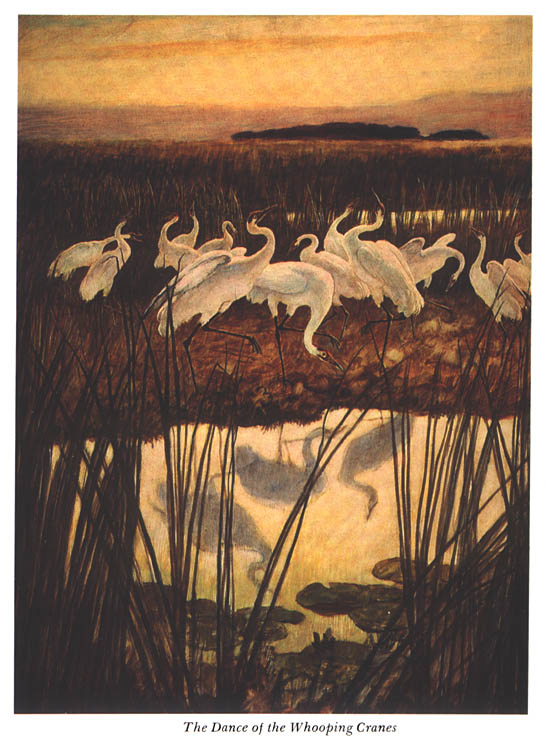

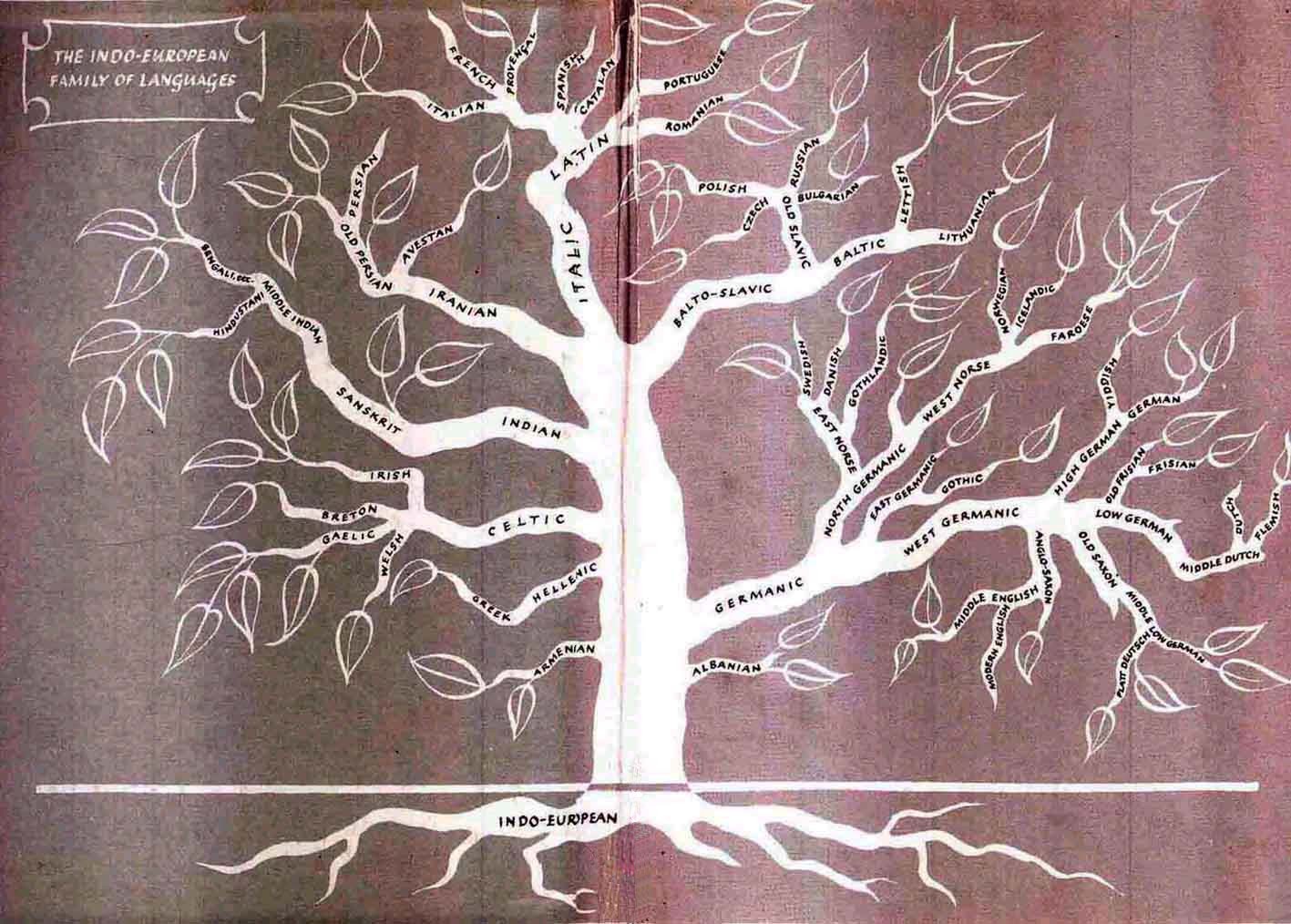

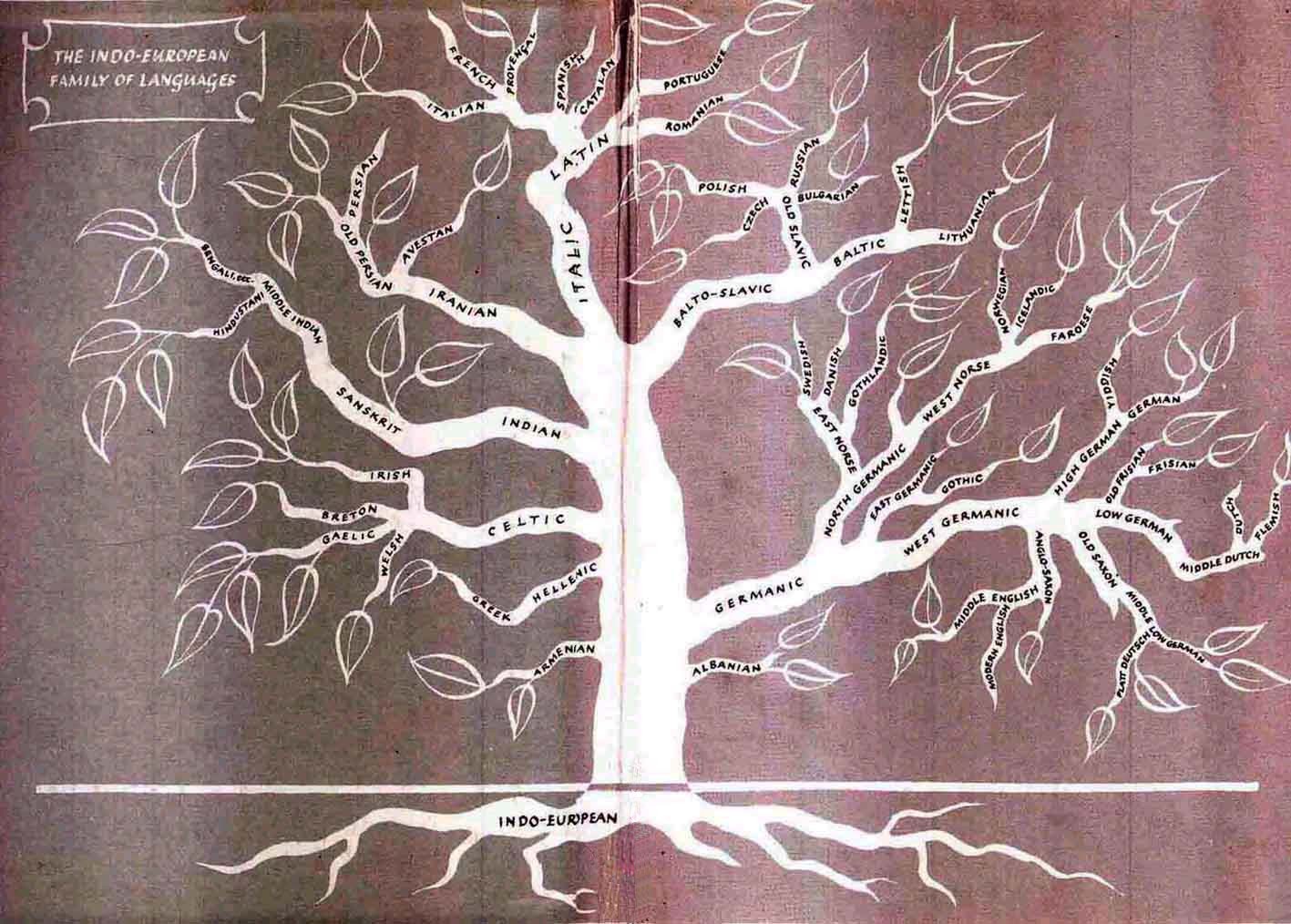

We must start from the multitude of ethnicities and cultures, from the tree of the peoples and cultures of the world, which is also the tree of life, the purer tree. Recognize, affirm this genuine, pure, natural, genuine multiplicity; watch over her, even protect her. Let us have it as sacred. In this tree we find ourselves, we recognize ourselves.

We are the Aryan or Indo-European branch (a term that refers to our languages and related cultures) of that eternal tree.

The first is the self-consciousness of a people: that individuals and members feel they belong to a people. First of all we have to regain the Aryan consciousness, Aryan memory, the voice, the word, the ancestral and indigenous being, the symbolic and collective identities. This will give us back the pride, dignity, and honor; the moral courage, in short: collective self-legitimation.

When someone insults, attacks, or damages a Norwegian (or a German, or a Frenchman, or an Englishman) the Aryan people are insulted. It is something that overwhelms the entire Aryan community. They humiliate their values, their existence, their being. Those are defeats for our people.

It is all, therefore, about our people, our land, and our cultures. We won’t condone grievances, threats or aggressions directed at our peoples or our pre-Christian or contemporary traditions. They’ll not go unpunished, unanswered. And it will be the same peoples who will respond. We will have a multitude of Aryan voices that will respond with white pride, Aryan pride.

♣

We find no value in these universalistic discourses in which we disappear as peoples and cultures. In this area, on these grounds, it is only possible to speak in the name of “humanity” or “universal man.” In these narratives our existence is not even recognized. The peoples, races, and nations are to be transcended, overcome, denied and become extinct to achieve the new and universal man. This is the eternal universal slogan, the old and the new, that our enemy offers to us, their Trojan horse, their poisoned apple: their insidiousness, their fallacy, their trap, their lie.

Should we expect anything else from the enemy—the old witch, the Jewish community—than “poisoned apples”? We should be wary of all that these misérables have been offering to us for thousands of years: Christianity, Marxism, psychoanalysis… These “productions” have no other function than to destroy: destroy our cultures, our status, our confidence in ourselves; to make us disappear, to eliminate us ethnically and culturally.

It is a very ancient war and so far we know only losses and defeats. With the Christianization of our people we lost our native and ancestral cultures. The modern movements (Marxism, psychoanalysis, the Frankfurt School, post-structuralism) will culminate the termination process initiated by those apostles of European gentility. Nothing differentiates the “Peters” and “Pauls” of the past from Marx, Freud, Boas, Adorno, Marcuse, Derrida of our time. The same purpose, the same intention.

♣

The Aryan peoples ought to be against religious, economic and political ideologies of Semitic origin (Judaism, Jewish Messianism, Islam, Communism); against the major disseminators of these universal creeds whose invention had no other purpose than disseminating discord and dissension within a people, and to divide and confront them.

Against the intricate Semitic network! Against the universal spider! Against universalism, totalitarianism, the homogenization (Messianic Jewish, Muslim, Democrat or Communist) of the planet! Against the destroyers of peoples and cultures! This is the mission. This is our struggle, unser Kampf.

Behold the dragon, the hydra, the eternal enemies of our people and light: Vritra, Typhon, Surt. They are the dark, the gloomy, the sinister. We will make war wherever they are located. Until their extinction. We will get the entire planet rid of this serious pest. In honor of the first Aryan nation, the birth of our nation. In honor of its creator.

Ad maiorem Hitleri gloriam (AMHG).