Chapter IV of Will and Ariel Durant’s The Lessons of History is titled “Race and History.” Although one of my favorite books is Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy (1926), the Durants were already in the train on its way to political correctness when, after the ten first volumes of their monumental The Story of Civilization (1935-1967), they published The Lessons of History in 1968.

It is symptomatic that in the blogosphere people like to quote chapter passages where the Durants subscribed to political correctness in racial maters (search for “Chapter IV” here): blaming the environment, not blacks, for the poor cultures at Sub-Saharan Africa and concluding the chapter with the sentence that “racial antipathies” cannot be cured except by “a broadened education.”

Apparently the Durants were completely ignorant about IQ studies and HBD in general (see this splendid interview of Henry Harpending by Craig Bodeker). Also, when in the chapter on race in The Lessons of History they write about Mayan and Aztec cultures they completely ignore that both cultures were based on organized serial killing. (See for example my own book chapter on pre-Columbian cultures, a subject that I am far more knowledgeable than the Durants.)

If any “lesson of history” has been learnt it is that you can write ten or eleven thick volumes about civilizations and, still, be totally immersed in the Matrix of your own age and culture.

Below, the complete Chapter IV, where the Durants try to rebutt the theory of Madison Grant:

There are some two billion colored people on the earth, and some nine hundred million whites. However, many palefaces were delighted when Comte Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau, in an Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines (1853-55), announced that the species man is composed of distinct races inherently different (like individuals) in physical structure, mental capacity, and qualities of character; and that one race, the “Aryan,” was by nature superior to all the rest:

Everything great, noble, or fruitful in the works of man on this planet, in science, art, and civilization, derives from a single starting point, is the development of a single germ; … it belongs to one family alone, the different branches of which have reigned in all the civilized countries of the universe… History shows that all civilization derives from the white race, that none can exist without its help, and that a society is great and brilliant only so far as it preserves the blood of the noble group that created it.

Environmental advantages (argued Gobineau) cannot explain the rise of civilization, for the same kind of environment (e.g., soil-fertilizing rivers) that watered the civilizations of Egypt and the Near East produced no civilization among the Indians of North America, though they lived on fertile soil along magnificent streams. Nor do institutions make a civilization, for this has risen under a diversity, even a contrariety, of institutions, as in monarchical Egypt and “democratic” Athens. The rise, success, decline, and fall of a civilization depend upon the inherent quality of the race. The degeneration of a civilization is what the word itself indicates—a falling away from the genus, stock, or race. “Peoples degenerate only in consequence of the various mixtures of blood which they undergo.” Usually this comes through intermarriage of the vigorous race with those whom it has conquered. Hence the superiority of the whites in the United States and Canada (who did not intermarry with the Indians) to the whites in Latin America (who did). Only those who are themselves the product of such enfeebling mixtures talk of the equality of races, or think that “all men are brothers.” All strong characters and peoples are race conscious, and are instinctively averse to marriage outside their own racial group.

In 1899 Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an Englishman who had made Germany his home, published Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century), which narrowed the creative race from Aryans to Teutons: “True history begins from the moment when the German with mighty hand seizes the inheritance of antiquity.” Dante’s face struck Chamberlain as characteristically German; he thought he heard unmistakably German accents in St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians; and though he was not quite sure that Christ was a German, he was confident that “whoever maintains that Christ was a Jew is either ignorant or dishonest.” German writers were too polite to contradict their guest: Treitschke and Bernhardi admitted that the Germans were the greatest of modern peoples; Wagner put the theory to music; Alfred Rosenberg made German blood and soil the inspiring “myth of the twentieth century”; and Adolf Hitler, on this basis, roused the Germans to slaughter a people and to undertake the conquest of Europe.

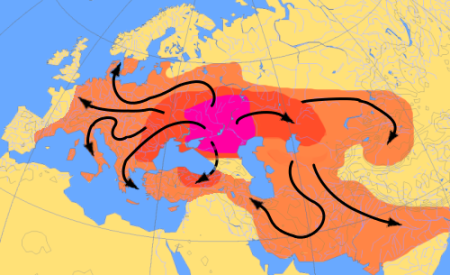

An American, Madison Grant, in The Passing of the Great Race (1916), confined the achievements of civilization to that branch of the Aryans which he called “Nordics”—Scandinavians, Scythians, Baltic Germans, Englishmen, and Anglo-Saxon Americans. Cooled to hardness by northern winters, one or another tribe of these fairhaired, blue-eyed “blond beasts” swept down through Russia and the Balkans into the lazy and lethargic South in a series of conquests marking the dawn of recorded history. According to Grant the “Sacae” (Scythians?) invaded India, developed Sanskrit as an “IndoEuropean” language, and established the caste system to prevent their deterioration through intermarriage with dark native stocks. The Cimmerians poured over the Caucasus into Persia, the Phrygians into Asia Minor, the Achaeans and Dorians into Greece and Crete, the Umbrians and Oscans into Italy. Everywhere the Nordics were adventurers, warriors, disciplinarians; they made subjects or slaves of the temperamental, unstable, and indolent “Mediterranean” peoples of the South, and they intermarried with the intermediate quiet and acquiescent “Alpine” stocks to produce the Athenians of the Periclean apogee and the Romans of the Republic. The Dorians intermarried least, and became the Spartans, a martial Nordic caste ruling “Mediterranean” helots. Intermarriage weakened and softened the Nordic stock in Attica, and led to the defeat of Athens by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, and the subjugation of Greece by the purer Nordics of Macedonia and Republican Rome.

In another inundation of Nordics—from Scandinavia and northern Germany—Goths and Vandals conquered Imperial Rome; Angles and Saxons conquered England and gave it a new name; Franks conquered Gaul and gave it their name. Still later, the Nordic Normans conquered France, England, and Sicily. The Nordic Lombards followed their long beards into Italy, intermarried, and vitalized Milan and Florence into a Renaissance. Nordic Varangians conquered Russia, and ruled it till 1917. Nordic Englishmen colonized America and Australia, conquered India, and set their sentinels in every major Asiatic port.

In our time (Grant mourned) this Nordic race is abandoning its mastery. It lost its footing in France in 1789; as Camille Desmoulins told his cafe audience, the Revolution was a revolt of the indigenous Gauls (“Alpines”) against the Teutonic Franks who had subjugated them under Clovis and Charlemagne. The Crusades, the Thirty Years’ War, the Napoleonic Wars, the First World War depleted the Nordic stock and left it too thin to resist the higher birth rate of Alpine and Mediterranean peoples in Europe and America. By the year 2000, Grant predicted, the Nordics will have fallen from power, and with their fall Western civilization will disappear in a new barbarism welling up everywhere from within and from without. He wisely conceded that the Mediterranean “race,” while inferior in bodily stamina to both the Nordics and the Alpines, has proved superior in intellectual and artistic attainments; to it must go the credit for the classic flowering of Greece and Rome; however, it may have owed much to intermarriage with Nordic blood.

Some weaknesses in the race theory are obvious. A Chinese scholar would remind us that his people created the most enduring civilization in history—statesmen, inventors, artists, poets, scientists, philosophers, saints from 2000 b.c. to our own time. A Mexican scholar could point to the lordly structures of Mayan, Aztec, and Incan cultures in pre-Columbian America. A Hindu scholar, while acknowledging “Aryan” infiltration into north India some sixteen hundred years before Christ, would recall that the black Dravidic peoples of south India produced great builders and poets of their own; the temples of Madras, Madura, and Trichinopoly are among the most impressive structures on earth. Even more startling is the towering shrine of the Khmers at Angkor Wat. History is color-blind, and can develop a civilization (in any favorable environment) under almost any skin.

Difficulties remain even if the race theory is confined to the white man. The Semites would recall the civilizations of Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Palestine, Phoenicia, Carthage, and Islam. The Jews gave the Bible and Christianity to Europe, and much of the Koran to Mohammed. The Mohammedans could list the rulers, artists, poets, scientists, and philosophers who conquered and adorned a substantial portion of the white man’s world from Baghdad to Cordova while Western Europe groped through the Dark Ages (c. 565-c. 1095).

The ancient cultures of Egypt, Greece, and Rome were evidently the product of geographical opportunity and economic and political development rather than of racial constitution, and much of their civilization had an Oriental source. Greece took its arts and letters from Asia Minor, Crete, Phoenicia, and Egypt. In the second millennium b.c. Greek culture was “Mycenaean,” partly derived from Crete, which had probably learned from Asia Minor. When the “Nordic” Dorians came down through the Balkans, toward 1100 b.c, they destroyed much of this proto-Greek culture; and only after an interval of several centuries did the historic Greek civilization emerge in the Sparta of “Lycurgus,” the Miletus of Thales, the Ephesus of Heracleitus, the Lesbos of Sappho, the Athens of Solon. From the sixth century b.c. onward the Greeks spread their culture along the Mediterranean at Durazzo, Taranto, Crotona, Reggio Calabria, Syracuse, Naples, Nice, Monaco, Marseilles, Malaga. From the Greek cities of south Italy, and from the probably Asiatic culture of Etruria, came the civilization of ancient Rome; from Rome came the civilization of Western Europe; from Western Europe came the civilization of North and South America. In the third and following centuries of our era various Celtic, Teutonic, or Asiatic tribes laid Italy waste and destroyed the classic cultures. The South creates the civilizations, the North conquers them, ruins them, borrows from them, spreads them: this is one summary of history.

Attempts to relate civilization to race by measuring the relation of brain to face or weight have shed little light on the problem. If the Negroes of Africa have produced no great civilization it is probably because climatic and geographical conditions frustrated them; would any of the white “races” have done better in those environments? It is remarkable how many American Negroes have risen to high places in the professions, arts, and letters in the last one hundred years despite a thousand social obstacles.

The role of race in history is rather preliminary than creative. Varied stocks, entering some locality from diverse directions at divers times, mingle their blood, traditions, and ways with one another or with the existing population, like two diverse pools of genes coming together in sexual reproduction. Such an ethnic mixture may in the course of centuries produce a new type, even a new people; so Celts, Romans, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes, and Normans fused to produce Englishmen. When the new type takes form its cultural expressions are unique, and constitute a new civilization—a new physiognomy, character, language, literature, religion, morality, and art. It is not the race that makes the civilization, it is the civilization that makes the people; circumstances geographical, economic, and political create a culture, and the culture creates a human type. The Englishman does not so much make English civilization as it makes him; if he carries it wherever he goes, and dresses for dinner in Timbuktu, it is not that he is creating his civilization there anew, but that he acknowledges even there its mastery over his soul. In the long run such differences of tradition or type yield to the influence of the environment. Northern peoples take on the characteristics of southern peoples after living for generations in the tropics, and the grandchildren of peoples coming up from the leisurely South fall into the quicker tempo of movement and mind which they find in the North.

Viewed from this point, American civilization is still in the stage of racial mixture. Between 1700 and 1848 white Americans north of Florida were mainly Anglo-Saxon, and their literature was a flowering of old England on New England’s soil. After 1848 the doors of America were opened to all white stocks; a fresh racial fusion began, which will hardly be complete for centuries to come. When, out of this mixture, a new homogeneous type is formed, America may have its own language (as different from English as Spanish is from Italian), its indigenous literature, its characteristic arts; already these are visibly or raucously on their way.

“Racial” antipathies have some roots in ethnic origin, but they are also generated, perhaps predominantly, by differences of acquired culture—of language, dress, habits, morals, or religion. There is no cure for such antipathies except a broadened education. A knowledge of history may teach us that civilization is a co-operative product, that nearly all peoples have contributed to it; it is our common heritage and debt; and the civilized soul will reveal itself in treating every man or woman, however lowly, as a representative of one of these creative and contributory groups.

(Here Pierce writes several paragraphs about the conquest of India, then he adds:)

(Here Pierce writes several paragraphs about the conquest of India, then he adds:)