27th March 1942, midday

Jewish influence on German art

—Painting in Germany.

It’s striking to observe that in 1910 our artistic level was still extraordinarily high. Since that time, alas! our decadence has merely become accentuated. In the field of painting, for example, it’s enough to recall the lamentable daubs that people have tried to foist, in the name of art, on the German people.

This was quite especially the case during the Weimar Republic, and that clearly demonstrated the disastrous influence of the Jews in matters of art. The cream of the jest was the incredible impudence with which the Jew set about it! With the help of phony art critics, and with one Jew bidding against another, they finally suggested to the people—which naturally believes everything that’s printed—a conception of art according to which the worst rubbish in painting became the expression of the height of artistic accomplishment. The ten thousand of the élite themselves, despite their pretensions on the intellectual level, let themselves be diddled, and swallowed all the humbug. The culminating hoax—and we now have proof of it, thanks to the seizure of Jewish property—is that, with the money they fraudulently acquired by selling trash, the Jews were able to buy, at wretched prices, the works of value they had so cleverly depreciated. Every time an inventory catches my eye of a requisition carried out on an important Jew, I see that genuine artistic treasures are listed there. It’s a blessing of Providence that National Socialism, by seizing power in 1933, was able to put an end to this imposture.

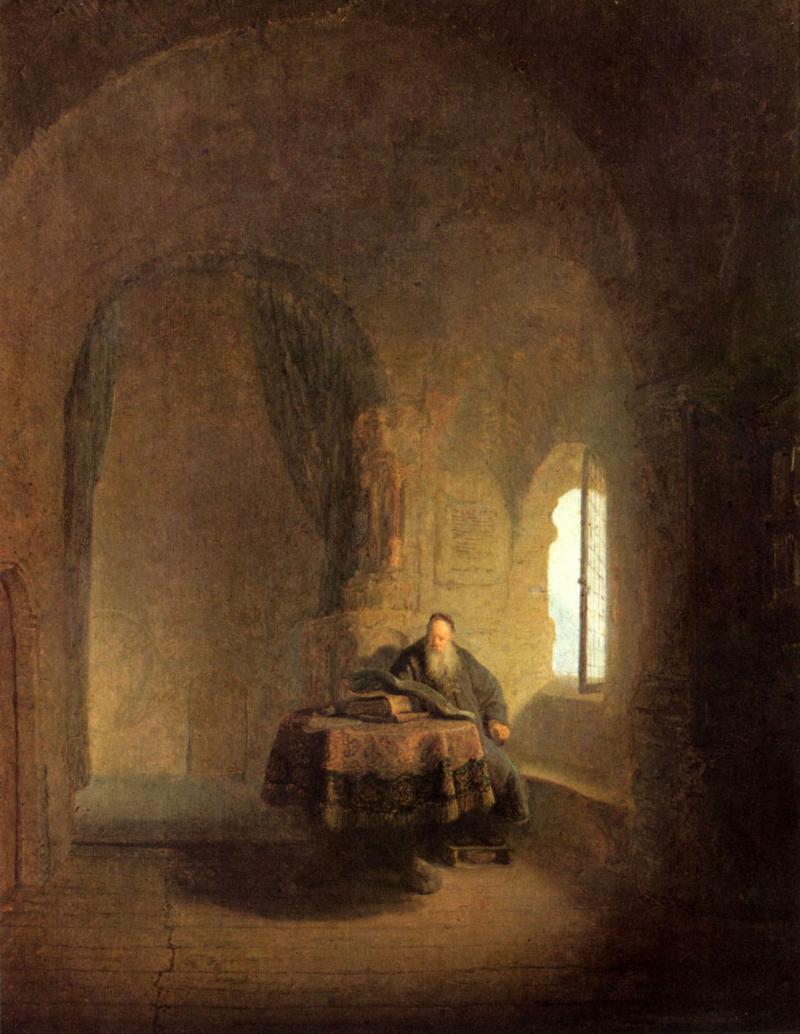

Genuine artists develop only by contact with other artists. Like the Old Masters, they began by working in a studio. Let’s remember that men like Rembrandt, Rubens and others hired assistants to help them to complete all their commissions.

Amongst these assistants, only those reached the rank of apprentice who displayed the necessary gifts as regards technique and adroitness—and of whom it could be supposed that they would in their turn be capable of producing works of value. It’s ridiculous to claim, as it’s claimed in the academies, that right from the start the artist of genius can do what he likes. Such a man must begin, like everyone else, by learning, and it’s only by working without relaxation that he succeeds in achieving what he wants. If he doesn’t know the art of mixing colours to perfection—if he cannot set a background—if anatomy still has secrets for him—it’s certain he won’t go very far! I can imagine the number of sketches it took an artist as gifted as Menzel before he set himself to paint the Flute Concert at Sans-Souci.

It would be good if artists to-day, like those of olden days, had the training afforded by the Masters’ studios and could thus steep themselves in the great pictorial traditions. If, when we look at the pictures of Rembrandt and Rubens, for example, it is often difficult to make out what the Master has painted himself and what is his pupils’ share, that’s due to the fact that gradually the disciples themselves became masters.

What a disaster it was, the day when the State began to interfere with the training of painters! As far as Germany is concerned, I believe that two academies would suffice: in Düsseldorf and Munich. Or perhaps three in all, if we add Vienna to the list. Obviously there’s no question, for the moment, of abolishing any of our academies. But that doesn’t prevent one from regretting that the tradition of the studios has been lost.

If, after the war, I can realise my great building programme—and I intend to devote thousands of millions to it—only genuine artists will be called on to collaborate.