To what should we compare God’s imperial rule, or what parable should we use for it? Consider the mustard seed. It is the smallest of all the seeds on the earth—yet when it is sown, it comes up and becomes the biggest of all garden plants, and produces branches, so that the birds of the sky can nest in its shade.

—Mark 4:30-31.

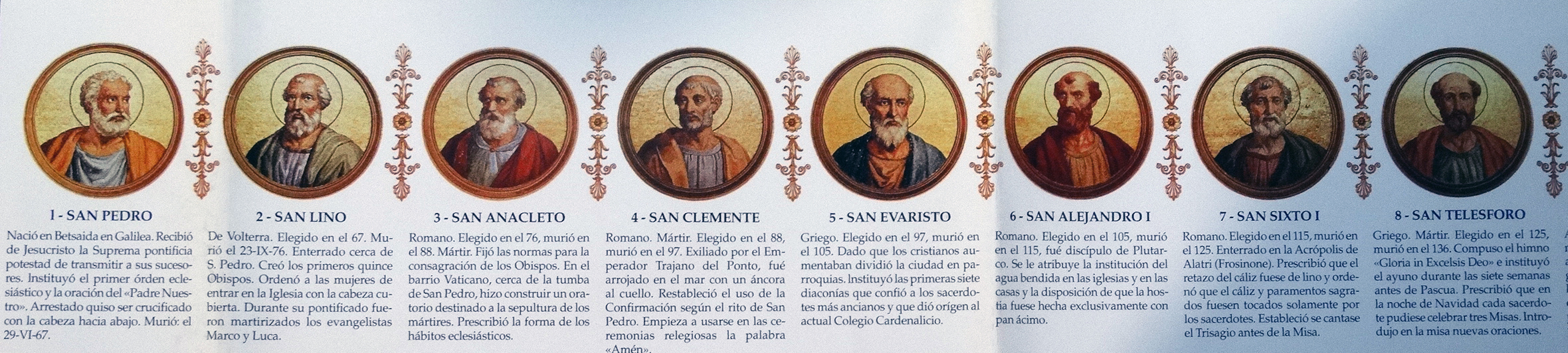

On Wednesday night I added a disclaimer to my post about the Epistle of James. I confessed that, mistakenly, I had used the New Testament (NT) chronologically ordered by a Christian fundamentalist. Instead, I’ll be using the order of Marcus Borg (1942-2015), a more reliable scholar, for the 27 books of the NT.

The earliest book in the NT according to this more serious scholar is not the Epistle of James but 1 Thessalonians, an original letter of Paul’s. The last book in the NT is 2nd Peter, not the Book of Revelation. Borg died three years ago but in the website of the Marcus J. Borg Foundation we can be read:

Chronological means ‘contextual’. What we see is how the message about Jesus developed or ‘evolved’. Paul’s letters to the early ‘Christ communities’ were written some 20 years earlier than the first gospel. And some letters attributed to Paul were written after his death!

The gospel of Mark was written around 70 and the other gospels written later, Matthew in the 80’s or early 90’s. They are obviously not firsthand accounts. And their stories don’t match. Does this surprise you?

Our New Testament [in the common Bible] is not chronological. Why do you think the NT was ordered the way it was?

In my forthcoming NT series the goal is to read the NT in the order the books were written, and share my impressions. Once it is understood that the oldest NT texts consist of fewer legendary layers about who the historical Jesus might have been, it is a real treat to read them.

Instead of the list that mistakenly I had published (the list by a Christian fundamentalist) the order that I will be using appears in Evolution of the Word: The New Testament in the Order the Books Were Written. Letters in grey below mean that these books are forgeries in the sense that the real authors are not those that the NT book claims authorship. The following dates are taken from the last pages of Evolution of the Word.

The 30s CE. Jesus is executed in ca. 30. His followers continue his mission in the Jewish homeland, especially in Galilee. Somehow, Christ-communities reached Syria, in the Jewish Diaspora beyond the homeland and Paul is converted in ca. 33-35.

The 40s CE. Emperor Caligula orders the erection of a statue in the Jerusalem Temple, sparking massive Jewish resistance while Paul is in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey). The controversy about whether gentile converts need to become Jewish—that is, circumcision for males—means that the Jerusalem church differed in principle from the incipient Pauline church.

The 50s CE. The seven genuine letters of Paul were apparently written in Greece and Asia Minor:

First Thessalonians

Galatians

First Corinthians

Philemon

Philippians

Second Corinthians

Romans

The 60s. Armed revolt against the Roman occupation in the Jewish homeland begins (cf. the essay that is still the masthead of The West’s Darkest Hour: ‘Rome vs. Judea; Judea vs. Rome’).

The 70s. In 70, Roman legions re-conquer Jerusalem and destroy the temple. Probably a majority of Jesus’ followers live in the Diaspora. Although the four gospels were anonymous writings and the later Church invented the names of the evangelists, I am not using grey letters for them because the intention of the authors was not to claim authorship for Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. (This does not mean that books in black letters are reliable biographical or historical accounts.)

Mark

The 80s and onward. The centre of Judaism in the homeland moves to Galilee. Judaism and the followers of Jesus begin to separate into two different religions. Second- and third- generation Christians struggle in an alien, Gentile world.

James

Colossians

Matthew

Hebrews

The 90s. The earliest reference to Jesus in a non-Christian source (Josephus), albeit tampered by the Christian scribes in the extant copies of Josephus. The extreme anti-Roman—i.e., anti-white—stance of the Christ cult by the end of the siècle is manifest in the lyric and stunning book by John of Patmos, inspired by the literary genre known as Jewish apocalyptic.

John

Ephesians

Revelation

The 100s. These NT books were written already in the second century of the Christian Era.

Jude

1 John

2 John

3 John

The 110s. Earliest references to Jesus and Christianity in Roman sources: Tacitus, Suetonius and Pliny. Unsuccessful Jewish revolt in Egypt because of tensions between Jews and white Hellenes.

Luke

Acts

Second Thessalonians

First Peter

First Timothy

Second Timothy

Titus

The 120s. A century after the preaching career of Jesus the last canonical NT book is written.

Second Peter

The 130s. The Jewish revolt against the Roman rule in the Jewish homeland is brutally suppressed by the Romans. The surviving Jews are exiled from Jerusalem (132-135). Since the Romans could not be defeated physically, the exiled Jews resort to psychological warfare through the universalist, Pauline version of the Jesus cult (‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Yeshua the anointed one’).

Catholic means ‘universal’ and, after centuries of infiltration that culminated in a hostile takeover, Constantine and his Christian successors would enforce universalism throughout the Roman Empire even though it would mongrelise whites in Constantinople: something unthinkable in the early Roman Republic.

Putting aside for the moment the catastrophe that represented Constantine’s House for the Greco-Roman gene pool, in a chronologically ordered NT everything started with the Semite Paul. Therefore, let us take a closer look at the first mustard seed that would conquer Rome.

As can be seen in the above list, the seven genuine letters of Paul are the earliest NT writings. But the epistles are highly problematic for the traditional Christian. Unlike the four gospels, replete with Jesus sayings and stories about his deeds, shocking as it may seem the earliest phase of NT writings provide almost no substantial information about Jesus. Gifted writers Mark, Matthew, Luke and John, who were kind of novelists, would fill the gap decades later with moving Jesus narratives.

As can be seen in the above list, the seven genuine letters of Paul are the earliest NT writings. But the epistles are highly problematic for the traditional Christian. Unlike the four gospels, replete with Jesus sayings and stories about his deeds, shocking as it may seem the earliest phase of NT writings provide almost no substantial information about Jesus. Gifted writers Mark, Matthew, Luke and John, who were kind of novelists, would fill the gap decades later with moving Jesus narratives.

The Christianity that bequeathed us Rome was not the Christianity of the Jerusalem Church led by Peter and James, but the Christianity of a newcomer from Tarsus who never met Jesus in the flesh. But who was this Saul, whose version of Christianity was the one that eventually triumphed over the competing sects throughout the Roman Empire? Certainly he was a man with a religious imagination of a high order who managed to transform Jesus’ prosaic death into something fantastic for the Hellenes.

These decadent gentiles, some of whom thought that the god of the Jews was the most powerful of all gods, loved mystery cults: the New Age of the degenerate Roman Empire. In a chronological reading of the NT, Paul, not Yeshua, is present from the very first word of the movement that resulted in Christianity. Compared to him the twelve apostles, the genuine depositaries of the Jesus cult, are shadowy figures in the NT epistolary, as none of them left authentic epistles according to modern scholarship (cf. the first chapters of our translated book of Karlheinz Deschner’s Christianity’s Criminal History).

Saul moved to Jerusalem as a grown man. Christian scholars have him in very high regard and take his word, that he stood for the Jewish tradition. But Saul, who became Paul after his mental breakdown on the road to Damascus, fits the words in Rome vs. Judea; Judea vs. Rome: ‘This was a sinister Jewish and Greco-decadent schizophrenia that is evident in the very name of Jesus Christ: Yeshua, a Jewish name, and Christos, ‘the anointed one’ in Greek. To give examples of the insane Romanisation of Judea that echo the hybrid Yeshua-Christos…’

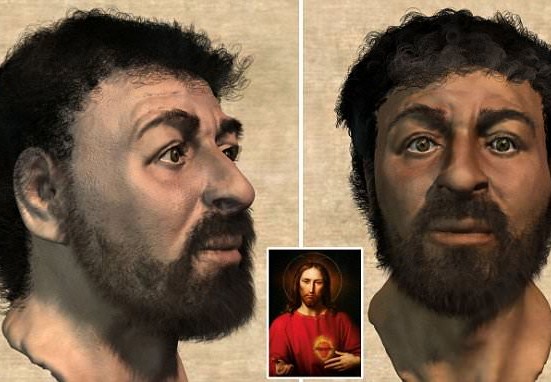

Hermann Samuel Reimarus was the first NT scholar that glimpsed who the historical Yeshua might have been, an apocalyptic seer that became frustrated when the eschaton did not occur. This historical Jesus, discovered by Reimarus and popularised by Albert Schweitzer, never had the intention to found a new religion. It was Paul the one who abrogated the Torah and created an amalgam between a mystery cult (that some scholars surmise he heard of in Tarsus) and esoteric Judaism. In his letters Paul claimed to be a Jew. Since Jews are the masters of deceit it does no harm to quote a modern (((scholar))) who specialised in the NT:

Paul, as the personal begetter of the Christian myth, has never been given sufficient credit for his originality. The reverence paid through the centuries to the great Saint Paul has quite obscured the more colourful features of his personality. Like many evangelical leaders, he was a compound of sincerity and charlatanry. Evangelical leaders of his kind were common at this time in the Greco-Roman world (e.g. Simon Magus, Apollonius of Tyana). [1]

Unlike the real disciples of Jesus who spoke Aramaic, Paul’s Greek is that of one who is a native speaker of the language. Hyam Maccoby (1924-2004), the author of the above paragraph, also said that Paul’s letters were written at a time when his break with the Jerusalem leaders was almost complete, and that Paul ‘refers to these leaders with hardly veiled contempt’.

The triumph of Pauline Christianity was overwhelming. After Paul’s death the teachings of the disciples of Peter and James were suppressed by the Romans, especially after Jerusalem was converted into Aelia Capitolina. In later generations, the remaining disciples of Peter and James were derogatorily called ‘Ebionites’ by the triumphant Church. The Ebionites regarded Jesus as messiah while rejecting his divinity and his virgin birth, and insisted—as precisely those that Paul criticises in his epistles—on the necessity of following Jewish law and rites.

The Ebionites revered Jesus’ brother James and rejected Paul as an apostate from the law. Since the Pauline Church eventually destroyed all texts of the competing denominations, Ebionite beliefs are only found in the writings of Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Tertullian, Origen, Epiphanius and Jerome: church authors discussed in Deschner’s Christianity’s Criminal History (cf. the September draft of Deschner’s book). Although we don’t have the Ebionite texts themselves, all of the above authors confirm that they opposed Paul as a pseudo-apostle and—most telling of all—claimed that Paul knew nothing about the true teachings of Jesus.

Analogous forms of exegesis moved Schweitzer and other exegetes reach the conclusion that the historical Jesus is unknowledgeable as the four gospels would be written under the influence of Pauline Christology; not of those who knew Jesus. In the opinion of several white men Paul was a superb mythologist, the real inventor of Christianity:

‘Paul was the first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus’. —Thomas Jefferson

‘Paul hardly ever allows the real Jesus of Nazareth to get a word in’. —Carl Jung

‘Paul’s words are not the Words of God. They are the words of Paul—a vast difference’. —Bishop John Spong

‘The new testament was less a Christiad than a Pauliad’. —Thomas Hardy

‘Paul created a theology of which none but the vaguest warrants can be found in the words of Christ… Fundamentalism is the triumph of Paul over Christ’. —Will Durant

‘Where possible Paul avoids quoting the teachings of Jesus, in fact even mentioning it. If we had to rely on Paul, we should not know that Jesus taught in parables, had delivered the sermon on the mount, and had taught his disciples the “Our Father”.’ —Albert Schweitzer

But of course, in The Quest of the Historical Jesus Schweitzer casts doubts about the historicity of most sayings attributed to Jesus. It is paradoxical that if the Romans had not destroyed Jerusalem and built on its ruins Aelia Capitolina, the original Yeshua cult, represented by Peter and James, might have conserved a few manuscripts refuting the claims of the opportunist from Tarsus.

Saul of Tarsus must have amalgamated a sort of proto-Gnostic ideas within Judaism with the bloody cult of a sacrificed god in his native town. For example, in death and Resurrection the god Attis represented, through his Resurrection, salvation for the degenerate inhabitants of the Greco-Roman world. The celebrants of Cybele’s mystery cult achieved salvation through the Resurrection of Attis. ‘When they are satisfied with their fictitious grief a light is brought in, and the priest, having anointed their lips, whispers, “Be of good cheer, you of the mystery. Your god is saved; for us also there shall be salvation from ills”,’ wrote Firmicus Maternus.

__________

[1] Hyam Maccoby: The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity (Harper & Row, 1986), p. 17. I read this book thirty years ago when I was living in San Rafael, California.