Editor’s Note: According to Tom Holland, Christian ethics surround us, even atheists, like water surrounds fish. Although Wikipedia is dominated by our ideological enemies, their article on Dominion is informative, so I’ve reproduced it in abbreviated form below.

Editor’s Note: According to Tom Holland, Christian ethics surround us, even atheists, like water surrounds fish. Although Wikipedia is dominated by our ideological enemies, their article on Dominion is informative, so I’ve reproduced it in abbreviated form below.

Although, unlike us, secular humanist Tom Holland subscribes to Christian ethics, and is therefore also an ideological enemy, anyone who understands the thesis of his book will understand the POV of The West’s Darkest Hour.

The racial right pundits I criticised yesterday are like fish in the axiological ocean that Christianity bequeathed us. They haven’t been able to venture onto dry land but, like the normies, have always been surrounded by the sea. After 1945, among the very notable racists in the US, only William Pierce dared, like the first fish to use its humble fins to venture onto the beach, to take his first steps out of the ocean. The rest remain wrapped in that matrix that prevents them from seeing the water from the dry land.

______ 卐 ______

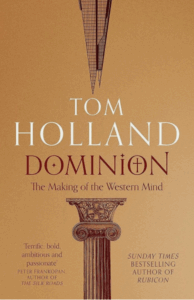

Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (published as Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World in the United States) is a 2019 non-fiction history book by British historian Tom Holland.

The book is a broad history of the influence of Christianity on the world, focusing on its impact on morality—from its beginnings to the modern day. According to the author, the book “isn’t a history of Christianity” but “a history of what’s been revolutionary and transformative about Christianity: about how Christianity has transformed not just the West, but the entire world.”

Holland contends that Western morality, values and social norms ultimately are products of Christianity, stating “in a West that is often doubtful of religion’s claims, so many of its instincts remain—for good and ill—thoroughly Christian”. Holland further argues that concepts now usually considered non-religious or universal, such as secularism, liberalism, socialism and Marxism, revolution, feminism, and even homosexuality, “are deeply rooted in a Christian seedbed”, and that the influence of Christianity on Western civilization has been so complete “that it has come to be hidden from view”.

It was released to generally positive reviews, although some historians and philosophers objected to some of Holland’s conclusions.

Background

Tom Holland has previously written several historical studies on Rome, Greece, Persia and Islam, including Rubicon, Persian Fire, and In the Shadow of the Sword. According to Holland, over the course of writing about the “apex predators” of the ancient world, particularly the Romans, “I came to feel they were increasingly alien, increasingly frightening to me”. “The values of Leonidas, whose people had practised a peculiarly murderous form of eugenics and trained their young to kill uppity Untermenschen by night [emphasis by Ed.], were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more.” This led him to investigate the process of change leading to today, concluding “in almost every way, what makes us distinctive today reflects the influence over two thousand years of the Christian story”.

Overview

In Holland’s view, pre-Christian societies and deities, such as in the Greco-Roman world, tended to focus on and glorify strength, might and power; this was inverted with the spread of Christianity, which proclaimed the primacy of the weak and suffering. Humanism, instead of springing from ancient Greek philosophy or Enlightenment thinking, “derives ultimately from claims made in the Bible: that humans are made in God’s image; that his Son died equally for everyone; that there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female.” The concept of human rights and equality, as well as solidarity with the weak against the strong, Holland argues, ultimately derive from the theology built on the teachings of Jesus and Paul the Apostle.

The success of what he calls the “Christian revolution” in changing our sensibilities, Holland argues, is evident in how complete its central claims now are taken for granted by “believers, atheists and those who never paused so much as to think about religion” [this includes white nationalists—Ed.]. Holland also argues that many of those who most clearly recognized the “radical” implications of Christianity, and its departure from earlier morality, were those fundamentally opposed to it—including Friedrich Nietzsche and the Nazi Party.

Reception

Terry Eagleton, writing for The Guardian, described the book as “an absorbing survey of Christianity’s subversive origins and enduring influence” and an “illuminating study”, concluding “Holland is surely right to argue that when we condemn the moral obscenities committed in the name of Christ, it is hard to do so without implicitly invoking his own teaching.” Philosopher John Gray, writing for the New Statesman, called Dominion “a masterpiece of scholarship and storytelling”. Gray wrote that “Dominion surpasses Holland’s earlier books in its sweeping ambition and gripping presentation… Holland comes into his own when he shows how Christianity created the values of the modern Western world… What makes the book riveting… is the devastating demolition job it does on the sacred history of secular humanism”.

Other reviews were more mixed. A review in The Economist described Holland as a “superb writer”, though also writing that “his theory has flaws”, and that “correlation is not causation”. Samuel Moyn, writing for the Financial Times, similarly stated that “Holland shines in his panoramic survey of how disruptive Christianity was for the ethical and political assumptions that preceded it”, while criticizing how “the illustration of the conquest of the west by Christianity risks becoming so total that it explains everything and nothing.” The scholars James Orr G.R. Evans and Samuel Moyn all regarded the book’s earlier sections on Ancient history as stronger than its later sections on more modern history. Evans writes that “The third section on “Modernitas” is perhaps the least successful, because of the degree of compression which it attempts”.

Peter Thonemann, writing for the Wall Street Journal, called Dominion “an immensely powerful and thought-provoking book”, stating “it is hard to think of another that so effectively and readably summarizes the major strands of Christian ethical and political thought across two millennia”. At the same time, he criticized its argument as selective, writing “Mr. Holland postulates a golden thread of Nice Christianity… this argument—that everything Nice in our contemporary world derives from Christian values, and everything Nasty in the actual history of Christendom was just a regrettable diversion from the true Christian path—seems to me to run dangerously close to apologetic”. The Los Angeles Review of Books stated that “Dominion’s most important contribution is in emphasizing how terms we take for granted, even concepts seemingly as fundamental as ‘religion’ and ‘secular,’ come ‘freighted with the legacy of Christendom'”, stating that his argument about the Christian origin of “human rights, socialism, revolution, feminism, science, and even the division between religion and the secular” is carried out in a “mostly convincing way”. Mendo Castro Henriques praised certain aspects of the book, but noted that the book omitted certain key figures such as Ignatius of Loyola, Thomas More and Erasmus and failed to pay attention to the profound importance of art and music throughout Christian history.

Many reviewers noted the distinctive approach used by Holland, centred on the lives and personalities of figures in history, as opposed to an in-depth history of ideas or theological analysis. Moyn described how “Holland brings the past to life through his characters, which are always vividly drawn”. Eagleton wrote how “Holland has all the talents of an accomplished novelist… Rather than unpack complex theological debates, the book gives us a series of vivid portraits of some key figures in Christian history”. Daniel Strand similarly wrote that “As opposed to intellectual history, which too often floats above historical events, Holland focuses on historical actors and their motivations”. Mendo Castro Henriques wrote, “Dominion is not a history of ideas, but of the body and soul of humanity.”

It was also favorably reviewed by the Sydney Morning Herald, The Critic, the New Yorker, and Kirkus Reviews who called it “an insightful argument that Christian ethics [emphasis by Ed.], even when ignored, are the norm worldwide.” In a mixed review, Gerard DeGroot, writing for The Sunday Times, wrote that he “[had] to commend the originality of this book” but disagreed with its thesis, writing “the values described as Christian seem more like simple human nature… The idea that charity and tolerance are evidence of Christian influence seems too ethnocentric”.

Philosopher A. C. Grayling has rejected Holland’s interpretation of Christianity’s influence on modern morality, meeting Tom Holland for a debate on the subject.

Influence

Despite being intended as a work of history and not apologetics, the book has since publication been cited as both an influential contribution to recent debates on “cultural Christianity”, and, for some, as a path to conversion in its own right. As such, this has in certain Christian milieus been described as the “Tom Holland train” to the Christian faith.

It was featured in The Atlantic as one of “Five Books That Changed Readers’ Minds”, where it was listed by Derek Thompson. American right-wing activist Charlie Kirk stated that reading Dominion helped convince him that the “canon of Western values” were rooted in Christianity.

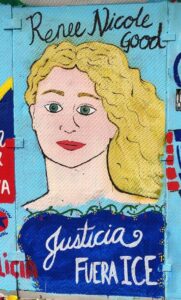

I didn’t want to comment on the killing of Renée Nicole Good. First off, it has nothing to do with me. The only link Good has to Ireland, is that she was a missionary in Northern Ireland.

I didn’t want to comment on the killing of Renée Nicole Good. First off, it has nothing to do with me. The only link Good has to Ireland, is that she was a missionary in Northern Ireland.