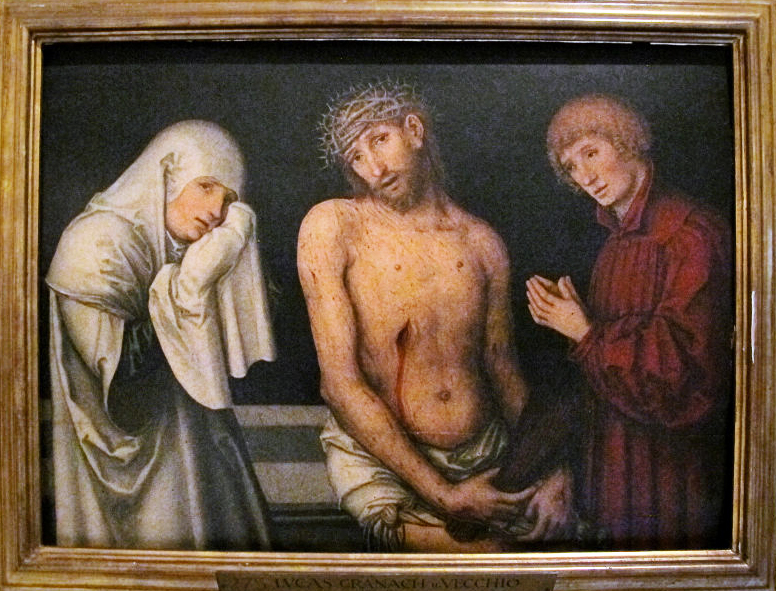

The Pietà is one of the most typical representations of the Passion of Jesus. Traditionally, it represents Mary and the disciple John contemplating Jesus once taken down from the cross.

The German Lucas Cranach the Elder, the same one who painted Martin Luther in one of his most famous portraits, here has Jesus and John as blonds. We cannot know if Mary was also blonde in the eyes of Lucas Cranach. Although this Renaissance painter was a close friend of Luther, this painting is in the Vatican Museum.

As Madison Grant already said in his introduction to The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World-Supremacy (1920), a book by Lothrop Stoddard, ‘from the time of Alexander the elimination of European blood… went on relentlessly’.

I agree with Adunai, and contra Robert Morgan, that there is no forced historical determinism in this process. Whites could have chosen good but chose evil instead, including pre-Christians like Alexander. The greed for power of both Alexander and Constantine lies at the root of the curse of miscegenation. It is tragic that, by subscribing Christianity, many white nationalists continue to surrender their will to evil. In ‘The Saxon Savior: Converting Northern Europe’, Ash Donaldson said:

______ 卐 ______

Alexander the Great & globalism

The seminal event in the ancient world was not the birth or crucifixion of Christ but the career of another man who preached universal brotherhood, Alexander the Great. His conquest of Greece, and the subsequent centuries of rule by his successors over various kingdoms, proved disastrous for Greece politically, economically, ethnically, and culturally. Politically, it put an end to the last vestiges of self-rule that marked the Greek polis, as once-proud cities like Athens and Corinth had to get used to being ruled by potentates in distant capitals. Mercenary armies did their fighting, or rather fought over them, and patriotism all but disappeared. Economically, foreign gold flooded the market, leading to spiraling inflation, which crushed the farmers. The availability of goods from places with cheap labor eroded the ability of local producers to compete in the suddenly “global” economy Alexander’s conquests had produced.

Ethnically, Greeks themselves numbered no more than fifteen percent of the population of Alexander’s empire, vastly outnumbered by Middle Easterners. Today, less than half of Greek Y-chromosomes are of European origin, but with due credit to the Turks, this process began much earlier than people suppose, when Alexander the Great inaugurated mass weddings of thousands of his troops to non-Europeans (setting the example himself, as always).

Furthermore, the old borders of the polis, once so jealously guarded, had suddenly vanished, and a period of immigration by non-Europeans began. Free Greeks had always regulated the foreign population in their cities. In Athens, for instance, the metics were actually a class of freeborn Greeks who were simply not born to Athenian parents, and were thus not eligible to become citizens. Sparta forcibly expelled any foreigners on an annual basis. All of this changed once Greeks lost the self-rule that Aristotle argued can only exist in a small community.

Flooded by foreign influences and foreigners themselves, with no power to change their situation, the Greeks grew indifferent, forsaking their old ways and their old Gods for fashionable escapes from society like Cynicism, Epicureanism, or foreign cults. With the death of the polis, Greek culture itself essentially came to an end. What remained were merely second-rate thinkers and dime-novel writers warming themselves over the embers of Plato and Homer.

Wherever people decide their own destinies in small, ethnically homogenous communities, we find cultural self-confidence and a flourishing of art, be it visual or literary. But wherever people feel hemmed in, ethnically isolated, and powerless, we find them seeking spiritual palliatives from foreign sources to alleviate their alienation and give them a sense of belonging.

Editor's note: Here the author reproduces an ancient Roman painting to make the point that some Roman citizens of the late Roman Empire were already mudbloods.

Before passing on to the religious ramifications of this titanic change in the ancient world, we should note that Rome, though it was originally a polis, adopted the Alexandrian globalist model.

According to this view, the community can expand indefinitely, ethnic and cultural borders are meaningless, and a civilization can survive the gradual disappearance of its original ethnic stock.

As early as the second century BC, the “Punic curse” of Rome’s conquest of its Mediterranean rivals was flooding Italy with foreign slave labor that tilled vast plantations, driving the free farmer out of business and chasing him into the city, where his descendants would grow up without any sense of community or local tradition. The results of mass immigration and racial intermarriage can be seen in portraits that survived the destruction of the Italian resort-town of Pompeii in the first century AD.

By that time, Roman women were dying their hair blonde and using lead acetate to make their skin whiter, in an effort to mimic the appearance of the original Romans and the few surviving noble families. Regardless of what the citizenship rolls said at any given time, centuries of population transfer had made true Romans so rare as to be statistically insignificant.