For an introduction to these series, see here.

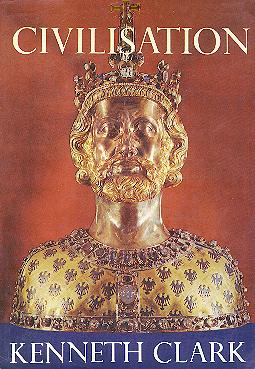

Below, some indented excerpts of “The Great Thaw,” the second chapter of Civilisation by Kenneth Clark, after which I offer my comments.

Ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages:

There have been times in the history of man when the earth seems suddenly to have grown warmer or more radio-active… I don’t put that forward as a scientific proposition, but the fact remains that three or four times in history man has made a leap forward that would have been unthinkable under ordinary evolutionary conditions. One such time was about the year 3000 BC, when quite suddenly civilisation appeared, not only in Egypt and Mesopotamia but in the Indus valley; another was in the late sixth century BC, when there was not only the miracle of Ionia and Greece—philosophy, science, art, poetry, all reaching a point that wasn’t reached again for 2000 years, but also in India a spiritual enlightenment that has perhaps never been equalled.

But what people don’t always realise is that it all happened quite suddenly—in a single lifetime.

In the brainwashed United Kingdom of the late 1960’s it would not have occurred Clark that another great awakening had occurred in Germany during his lifespan, just thirty years before; and that it was crushed by the forces of evil led by the government of his country. Speaking about Christendom at the beginning of the second millennium of the Common Era, on the next page Clark continues:

How had all this suddenly appeared in Western Europe? Of course there are many answers, but one is overwhelmingly more important than the others: the triumph of the Church.

And here Clark omitted to mention what he implied in the previous chapter: that in the first millennium the role of the Church was destructive, as surmised in his paragraph about St. Gregory who destroyed entire libraries of classical knowledge (search for “St. Gregory” here). After starting to describe the medieval period that our silly high schools completely ignore, six pages later Clark mentioned the most emblematic feature of the age:

On the physical side this took the form of pilgrimages and crusades. I think they are among the features of the Middle Ages which it is hardest for us to understand. Pilgrimages were undertaken in hope of heavenly rewards. How can one hope to share this belief which played so great a part in medieval civilisation?

Later in the series I loved to see Clark saying that he never bothered to understand economics, because this is one of the things that contemporary historians, so alienated by Marxism will never understand.

In my childhood I received a medieval education from my father. When during my adolescence he started to abuse me, the doctrine of eternal damnation that he had inculcated me since childhood metamorphosed into an internal persecutor. It didn’t matter that I managed to escape my parents’ home and moved to San Rafael in the US: the internal persecutors accompanied me throughout my twenties.

When I asked for help to the organization known as Fundamentalists Anonymous by regular mail I received a dumb reply that greatly offended me, as I recount in my last book of Hojas Susurrantes. Although technically I had already abandoned the faith I then asked for help, always through regular mail, to John J. Heaney who taught theology at Fordham University. It was the Christian Heaney, not the silly rationalists of Fundamentalists Anonymous, who immediately understood what my inner agonies really meant and tried to help, at least in the modest form of an epistle. (These were times before the electronic mail became fashionable.)

Modern rationalists who find pilgrimages hard to understand lack elemental empathy toward the Other. Even Clark, when he talks of pilgrimages undertaken “in hope of heavenly rewards,” understates what a brutally-honest historian would have said instead: undertaken in hope of saving one’s soul from the eternal fire.

I mention this personal vignette because, despite claims to the contrary, history will never be understood “objectively.” We need the subjective experiences of the survivors of a given culture, even if such experiences were written by latter-day Christians and apostates: a sphere of knowledge altogether alien for the naïve historian who’s afraid to enter the tragic, subjective universes.

But Clark was infinitely superior to the Mr. Spock historian who currently controls the universities. On the next page he states:

Of course the most important place of pilgrimage was Jerusalem. After the tenth century, when a strong Byzantine empire made the journey practicable, pilgrims used to go in parties of 7,000 at a time. This is the background of that extraordinary episode in history, the First Crusade.

The crusades aside, several pages later Clark speaks of the author of The Heavenly Hierarchies:

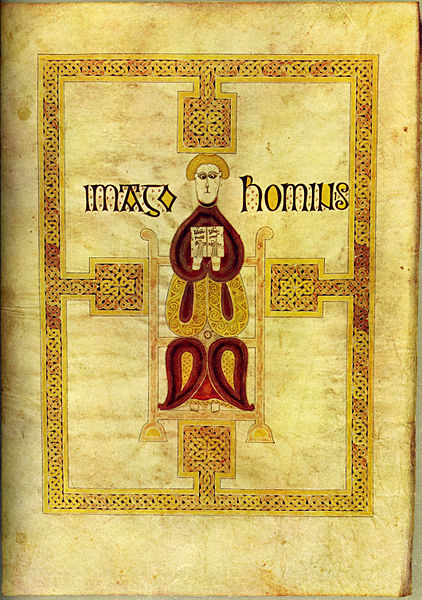

He argued that we could only come to understand absolute beauty, which is God, through the effect of precious and beautiful things on our senses. He said: ‘The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material.’ This was really a revolutionary concept in the Middle Ages. It was the intellectual background of all sublime works of art in the next century and in fact has remained the basis of our belief in the value of art until today.

“Today” still meant 1969, when Clark’s body language and voice were recorded by the BBC. Not anymore. Presently many whites seem to loathe traditional works of art not only by labelling them “kitch” but by praising instead degenerate forms of cultural expression. That this happens even among white nationalists, the watchdogs of the West, should be enough to convince the honest reader that something really odd is gong on in the white psyche, and that we hardly can blame the Jews for all our problems.

Following next Clark takes us to that place where the dull mind, even the atheist’s mind, rises indeed through the matter, Chartres Cathedral:

Chartres was the centre of a school of philosophy devoted to Plato, and in particular to his mysterious book called the Timaeus, from which it was thought that the whole universe could be interpreted as a form of measurable harmony.

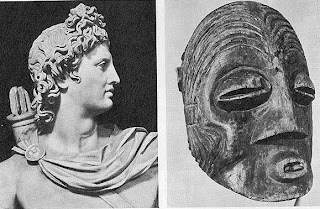

Figures had been made into columns since the Cnidian treasury at Delphi, but never so narrowly compressed and elongated as they are here. I fancy that the faces which look at us from the past are the surest indication we have of the meaning of an epoch.

Once more the chronicles describe how people came from all over France to join the work, how whole villages moved in order to help provide for the workmen; and of course there must have been many more of them this time, because the buildings was bigger and more elaborate, and required hundreds of masons, not to mention a small army of glass-makers.

Chartres is the epitome of the first great awakening in European civilisation.

Absolute beauty, the God of the post-Christian, not evil music or Hollywood treason has a chance to bring into being another great awakening…