‘He alone, who owns the youth, gains the future’.

—Hitler

‘He alone, who owns the youth, gains the future’.

—Hitler

(21 November 1947 – 4 December 2024)

Michael Thomas Goodrich (born Michael Thomas Schoenlein), the author of what I consider the most important book written in English this century, died on Wednesday.

Not long ago, I exchanged my last correspondence with him, telling him I wanted to promote his books on this site; today, his publisher confirmed that he had passed away (see this Thursday’s interview esp. from 1:50).

Even in the last book of my autobiography in Spanish, I leave the reader with the thankless task of reading Hellstorm since without that reading, my mental transformation—from liberal to conservative, from conservative to white nationalist, and from white nationalist to National Socialist—could not be understood.

Goodbye, Tom. There are no writers like you left in your country. May some English speakers at least pick up your torch….

Three recent comments by a commenter motivate me to quote, in a single post, all his comments since last year, including recent ones:

Eradicating non-Aryan elements from the planet is a legitimate, sensible and practical strategy for continued existence for Aryankind. People captured by Neo-Christian morality condemn such actions as evil. But what greater evil is the complete extinction of Aryankind and degeneration into an Untermenschen cesspool.

—posted last year in the thread ‘Black Bread’.

In any given future Aryan Ethno-state, societies or communities, Christian-related materials will be only be available to those who are extremely racially sound and immune to the Christian poison. Such materials are only to be used for historical or academic research or evaluation. Individuals who are able to access such materials should be as ruthless as Heinrich Himmler and fiercely racially loyal or unpolluted as SS members.

—posted in the thread ‘On John Milton’.

In Adolf Hitler: The Ultimate Avatar by Miguel Serrano, (Miguel Serrano was one of Savitri Devi’s companions and compatriots), it reveals that Yahweh and its supposed son Jesus are the demiurge. Yahweh is the evil “god” of the world and it is demonic. Whether this hypothesis is true or not, Aryans are the true stepping stone for the next stage in human evolution. As time and the Kali Yuga advances, the forces of decay and disintegration at work as described by Savitri will accelerate their actions against the true divine spark and chosen race of humanity which is the Aryan. The ultimate endgame is the devolution of humanity back to the ape and Neanderthals.

—posted in the thread ‘Moloch = Yahweh’.

Yes, the Serpent, Molech, Baal, Satan and Yahweh are one and the same, this is true of all Semitic entities. Yahweh symbolizes the entirety of the forces of decay in our present age that bring Aryans to their final doom, it is the prime mover of the Kali Yuga. The day of salvation will finally arrive for the Aryan once Christian ethics are extirpated from the world forever. I am shocked that there are no rigorous and supportive reactions from Aryans to this post. [emphasis added by Ed.]

—posted in Ibid.

I just hope the seed planted will blossom into an even mightier tree than the poisonous weeds that are Christianity and Neo-Christianity. Racially healthy Aryans in any future Aryan civilization or society will look back on Christians and Christianity as abhorrent and ridiculous as dunking your face or body into a pool of pig swill. If all Aryans in the entire world start burning bibles in bonfires and smashing the last stones of these very last churches into the ground, we knew that we had finally won.

—posted in the thread ‘Crusade’.

The near perfect comtemporary antithesis of the Christian poison are Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, and members of the SS. The relentless and pathetic slander on Heinrich Himmler and the SS shows how afraid the racial enemies of the Aryan man are. It shows us a glimpse when Christian “values” and “ethics” (I would call that poison) are completely repudiated. Once the Christian poison is totally expunged from the soul of Aryan man, he is completely healthy again and it will be gameover for racial enemies, traitors and the world we known today.

—posted in the thread ‘Might is Right, 8’.

This is the precise reason it requires a systemic collapse of such unprecedented severity to weed out unworthy Aryans that are still entrapped in the snare of Christian ethics. The present status quo and the “world” as we knew it not only reinforce Christian ethics, it rewards and incentivizes them. The entire ludicrous and ridiculous notion of “last shall be first, the first shall be the last” will be proven false and illusory once the iron law of racial survival is the only way.

—posted today in the thread ‘Christian nationalism’.

I would like to say that the Christian “god”, which is a virulent mental virus [emphasis added by Ed.], is solely responsible for the population explosion of the racially and genetically inferior in the past few hundred years. It paves the way for Aryan extinction and it requires Kalki or an exterminationist solution to remedy it.

—posted in Ibid.

You might have a better chance of convincing a clumsy bull to climb or fly up a high wall than convincing Christian nationalists the error of their ways.

A racially-sound Aryan child or youth raised in a racially-healthy Aryan collective can easily understand the obvious contradiction of trying to preserve the biological existence of the entire Aryan collective and embracing a foreign Semitic god created from the foul sands of Judea.

Useless to state it again, many Christian nationalists are suffering from psychotic and schizophrenic ambiguity.

—posted in Ibid.

‘The day of individual happiness has passed.’

—Hitler

by Gaedhal

I was reading Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy (1946). According to Russel, theism died out amongst the best minds in Europe, by 1700. This is, incidentally, how we could have a secular government established in America in the 18th Century. Aron Ra put a recording of Madeline Murray O’ Hare where she claimed that all the founders of America were atheists. In my view, this is an exaggeration. However, a lot of them weren’t theists. Thomas Jefferson called himself a materialist, as did Abraham Lincoln, four score and seven years later. John Adams wondered whether God even existed at all… which qualifies him as an agnostic. If only rich land-owning white men can vote—and, remember, white aristocrats have been having outbreaks of atheism since the Ionic Enlightenment, about 500 years before the common era—then the form of government that they would chose for themselves would be a secular godless government, in no way founded upon the Christian Religion, where Religion is only referred to as a negative phenomenon that must not be imposed, by the State, upon its citizens.

The reason why I am an elitist, of sorts, is because the mob is more than 300 years behind the intellectual elite in abandoning theism. Thankfully, some countries, like the United Kingdom, are transitioning into a post-theistic age.

The Philosopher Kings who established the United States, were non-theists. There might have been some sort of Aristotelian prime mover, who got the Cosmos started, however, this God no longer tinkers with or prods his creation. Thomas Paine, although a believer in an Almighty, of some deistic sort, nevertheless categorically rules out miracles. Paine thinks it absurd that a God would fix the laws of nature… and then break these laws through performing miracles. Paine does offer some positive arguments for God, such as the argument for God through mathematics/geometry/platonic forms… however, a god who doesn’t do miracles might as well not exist.

God used to have a lot of jobs to do. Prior to Newton and Galileo, objects were said to “prefer” to be at rest. Thus God’s might was needed to push the planets about the sky. If the planets are motoring across the sky, then God must be pushing them about. However Galileo and Newton proved that objects were utterly indifferent as to their being in motion or at rest. Thus, God was no longer needed to push the planets about the sky.

The motto of the Royal Society, headed up by Newton was and is: verba in nullius, which is Latin for: “We take nobody’s word for it”. In Christianity, we believe things because a holy-man said it. This is why Saint Paul is always vaunting how holy he is… how many times he went to prison for god… how poor and hungry he is for god. How many times he got flogged by the enemies of the Christian God. The holier one was, the more trustworthy he was meant to be.

Verba in Nullius is thus an antichrist saying. Scientists don’t give a fuck how holy you are. You either demonstrate what you claim, or it is not established. The Royal Society, thus, does not really care what God says, what Jesus says, what a Pope says, what a Holy Book says… Science is only interested in demonstrable reality.

However, another job that God had was to animate living things. Living objects, thanks to a false idea inherited from Aristotle, were also said to prefer rest. The fact that living things existed at all was proof—yes proof!—that God exists. However, the Biochemistry of which living things is composed is also totally indifferent—it has no preferences—whether it be at rest or in motion. Thus, there is no need for a god to animate our bodies through a magical object called a ‘soul’—or, in Latin: ‘anima’. Thus, there is no longer any need for a Great Cartoonist in the Sky to animate Aristotelian rest-preferring biological bodies with souls.

Hell was also disbelieved in by 1700, according to Russell. Newton was a Unitarian, and so, by rights, he should be shrieking up his bloody lungs in fiery torment, in Yahweh’s superheated torture chamber. However, the idea that Newton was in Hell was too much to swallow.

To recap: the elitists who founded America had all of this sussed out by the founding. They were deists, agnostics, materialists etc.

However, 300 years later, amongst the American mob, the Christian Superstition, is still rife among the populace. America is in real danger of succumbing to Christian Nationalism.

The mob will eventually abandon theism in America, though, just as they have already done in the United Kingdom… however, the mob always seems to be centuries behind the intellectual elite.

To me, the chapter: ‘The Rise of Science’ really demonstrates the gulf that exists between the elite philosophers, and the superstitious mobmen.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s 2 ¢

In certain quarters of the American racial right, Christian nationalism is popular.

For someone who, like me, already admired pantheism since 1973 and 1974 when we were taught Hegel at school, and knew about the existence of the pantheist theologian Teilhard de Chardin, I am surprised by the atavisms that Americans still suffer from. If only the racialists would take Uncle Adolf’s after-dinner talks as their guidebook! But even before Hitler, philosophical-theological treatises had already been published in Germany, which distanced the readers from the theism that persists in the hemisphere where I live.

For someone who, like me, already admired pantheism since 1973 and 1974 when we were taught Hegel at school, and knew about the existence of the pantheist theologian Teilhard de Chardin, I am surprised by the atavisms that Americans still suffer from. If only the racialists would take Uncle Adolf’s after-dinner talks as their guidebook! But even before Hitler, philosophical-theological treatises had already been published in Germany, which distanced the readers from the theism that persists in the hemisphere where I live.

It is not surprising that Karlheinz Deschner’s work on Christian criminal history has been translated and published in Spanish but not published in English. And with such gross ignorance do the racialists pretend to lead their country forward?

The PDF of Revilo Oliver’s article

on Christianity is now available here.

…with few friends or no circle at all

(YouTube short by Jordan Peterson).

A religion for sheep, 6

by Revilo P. Oliver

Published by Liberty Bell Publications in 1980,

under Oliver’s nom de guerre Ralph Perier.

How the Jews hate Christianity

The Jews no longer make a serious effort to maintain the pretense of an antipathy to Christianity. It is true that once in a while they protest the public display of Christian symbols, such as the cross. But that merely spices their joke. When they erect a thirty-foot “menorah” in front of the White House to remind their tenant who owns the place, the cowed Christians never think of protesting.

Oliver, in his fairly well-known book, Christianity and the Survival of the West, claimed that it was a “Western” religion, but he had to base his argument on what had to be added to the doctrine to make it acceptable to the Nordic peoples after the collapse of the rotted Empire that had once been Roman. And in the postscript to his second edition, he admitted that the religion had been stripped of those additions and was being reduced to the superstition of the early Christian sects that either excluded non-Jews or admitted them only to the status of “whining dogs,” which they could attain by having themselves mutilated sexually, observing the Jewish taboos, and obeying their God-like masters.

John Hagee, a television evangelist who preaches a Christian doctrine that is totally centered on idolizing and supporting Jews and Israel.

The holiness of the Jews is now an established dogma, especially among the Ersatz-Christians. A friend of mine, who is now in the United States, wrote to presidents of various colleges and universities that were trying to make a few extra bucks by offering courses to prove the “truth” of the Jews’ hoax about the “six million” of God’s People that the Germans are supposed to have “exterminated” by a procedure that is physically impossible. He had several very nasty replies from chief diploma-salesmen who intimated that he, who holds a Ph.D. in modern history, should be locked up for his “ignorance.”

I have seen copies of some of those letters. The irate prexies were clearly endorsing their own faith. They knew that Jews could not lie, just as their grandfathers had known that Jesus walked on water and held a picnic that was the least expensive fish-fry in history. It boots not to inquire how much of their grandfathers’ faith or their own was founded on actual belief in what “everybody believes” and how much was based on a calculation that it would not be remunerative to doubt what “everybody knows.” The results are the same. Woe to him who questions any tale told by the “righteous” race.

By this time, everyone must know that the Jews have acquired a working control of all the media of communication: the press, the radio, the boob-tube, and the publication of widely-distributed books. If the Jews had the slightest animus against the Christian religion, they would use these powerful weapons to destroy it. Instead, the real opponents of Christianity, the rational atheists, are systematically and totally excluded from the “media.” No newspaper, no widely distributed periodical, dares print one of their articles or even to mention them without derision. No radio or television station will admit they exist, and even if they telephone on “call in” programmes, they are shut off before their first significant word reaches the antenna.

To get into print, they must organise their own starveling publishing companies to issue books or periodicals that are very expensive because only a few copies can be printed for a tiny audience that cannot be increased because no newspaper or radio could be hired to advertise such publications at any price. The managers, even if not Jews, prudently assume that atheists, who would substitute facts and reason for fairy tales and blind faith in “spiritual values,” are very wicked, and they regret that it is not currently feasible to burn them at the stake. If the Jews had an antipathy to Christianity, they could change that attitude overnight with a few directives to their hirelings, and they could make the religion ludicrous in the eyes of the majority within a year or two. The boobs simply absorb what they are told.

John Hagee, his wife and Trump.

The Jew-controlled “media” constantly and systematically lavish free publicity on the Christian churches and especially on the salvation-hucksters. The aether is clamourous with the bellowing and wheedling of “evangelists,” who are plying their trade and raking in money from everyone whose emotions can be stirred by their crude rhetoric. Even the richest of the gospel-businesses receive much of their advertising free; when they do have to pay, they are given much reduced rates. The “media” religiously report miracles that could have happened only East of the Sun and West of the Moon. And they religiously assume that the Christian shamans are so holy they must “mean well,” even when they are caught in embezzlement or fraud.

I hear that about half a dozen White preachers, more or less subtly “racist” or even anti-Jewish, are allowed to speak (for a fee) over some of the smaller radio stations in the United States, provided, of course, that they do no more than furtively intimate what they mean on racial subjects. If they really annoyed the Jews, they would be shut up on some pretext or other. The “evangelists” who make it to the big time (an annual take of ten million dollars or more) all make it clear that a Christian’s first obligation is to adore God’s People.

Furthermore, although the Christians and some sociologists miss the point, the “media” are industriously creating the atmosphere most propitious to a recrudescence of Christianity. The religion grew in the decaying Roman Empire with the growth of universal unreason: It had to compete only with other superstitions so gross that historians are perplexed when asked to decide which was the most grotesque.

The “media” are today stridently promoting every kind of hokum that encourages belief in the supernatural. They not only advertise, but even hire “psychics,” “seers,” astrologers, and mystery mongers who spin tall tales about haunted houses, weekends on “flying saucers,” “Bermuda Triangles,” and similar boob-bait. All the adepts of such cults are potential customers for the Christian fakirs. When, for example, a man begins to practise the self-hypnosis called “transcendental meditation,” he will soon ripen himself for an access of Faith. When he has so blunted his intelligence that he can believe that the planets, while obeying the law of gravitation with mathematical precision, took the trouble to portend his future, he can soon believe in the Second Coming and the End of Time.

I have seen no statistics that indicate how greatly the percentage of belief in the theological myths of Christianity has been increased by the Jews’ strenuous promotion of it, but I observe that in the United States the three clowns who recently competed for the job of doing the Jews’ work in the White House thought it good advertising to call for a “spiritual rebirth” and to claim that they had been laundered in “the blood of the Lamb” and “born again.” A candidate’s chances of winning the popularity-contest now seem to be increased by evidence that he either is a liar or has hallucinations.

The most stupendous of the Jews’ many hoaxes is a witch’s brew that has, over the centuries, transformed the once intelligent and valiant Aryans into flocks of uncomprehending sheep, easily herded, easily fleeced, and easily stampeded.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note:

After Alain de Benoist’s essay on Christianity, I’ll be posting a series on Revilo Oliver’s book mentioned above.

By the way, I’ve been taking these images from the republishing of this essay six years ago in National Vanguard (here). As you can see, Oliver died in 1994 and the images of the mad evangelist are from this century. Apparently, Rosemary Pennington of National Vanguard chose the images, and I think it was opportune to interpolate them into Oliver’s 1980 piece.

I am still missing an instalment of Revilo Oliver’s article but before I put it up I would like to say something about that essay. This passage from Oliver—:

They [the Aryans] are burdened by the horrible guilt of not having committed suicide, a guilt they can expiate only by taxing themselves to hire their enemies to destroy them. They must love their enemies, but hate their own children. Especially in once-great Britain and the United States, the crazed Whites are not only subsidising the proliferation of their vermin and legislating to inhibit the reproduction of their own kind, but are importing from all the world hordes of their biological enemies to destroy their posterity.

—made an impression on me. It made me think about my eternal criticism of the Judeo-reductionism of the American racial right, which has failed to realise that it is whites themselves who have hired their enemies to destroy them (consider, for example, the number of pro-Israel people Trump has chosen for his new cabinet). It is more than clear, as William Pierce once said, that if the Aryan doesn’t get the monkey (Christianity) off his back he will not survive.

Precisely because the monkey is carried by whites on both sides of the Atlantic, Benjamin observed the following in his latest email today:

Dear César,

I am reminded today of another outright example of ersatz Christians jeopardizing white racial struggle. As far as I recall, you suggest that in order to wake up and defend/attack ourselves in the UK we must pass through various stages, starting at stage 1 with the men getting angry enough at their circumstances to want to protect their own homes and families. I see something today, written by Blair Cottrell, but highlighted by Mark Collett, the head of Britain’s main nationalist group, would be a hinderance to this, shamefully encouraging head-in-the-sand cowardice and advising, in false pedagogy, to relinquish hatred. I remember making the comment before that these sinister group leaders seem to act like official counter-countersubversives. I’m sure they’re not, but their pacifist gatekeeping is infuriating. I was really hoping someone would take you up on your radio station podcasts idea. In the worst case scenario you could deliver monologues, or take questions/discussions after a short gap window, where listeners could use their own AI software to translate their (presumed) English to Spanish remarks then email the translated .wav files to you.

Anyhow, this is what Mark recommends:

If a person has ugly thoughts, it begins to show on the face. And when that person has ugly thoughts every day, every week, every year, the face gets uglier and uglier until it gets so ugly you can hardly bear to look at it.

I do believe this is true.

It’s why it’s important to psychologically protect yourself from certain people and circumstances.

It’s completely reasonable to resent the state, the suburbs, traffic, the condition of the culture, the 12 Indians in a rental across the street yelling jibberish at all hours of the night, etc., but only up to a certain point is it healthy to hate.

You need to remove yourself on occasion and allow yourself the space and time to reset & be thankful for what’s good. Your soul will thank you for it.

Mischaracterising healthy adult hatred as ‘ugly thoughts’ was duplicitous. By taking a reasonable idea and placing it in unreasonable context, he might as well work for Prevent. I think to begin to successfully cross to the other bank of the Rubicon one must truly hate their country.

Best regards,

Ben

Collett doesn’t even strike me as a pure Englishman from the point of view of his phenotype. I guess his genotype is compromised by racial garbage. But the important thing is that as long as the English don’t hate they will never get ahead. Not a hatred like Rudyard Kipling advocated against the Germans in WW1 but, now, a hatred of the whole British culture because of what they did since WW2.

Incidentally, Oliver’s essay is so important that I will merge it, after the sixth instalment, into a single PDF to be accessed in the featured post, ‘The Wall’. But as I no longer want to edit that article, I will upload ‘The Wall’ again on 1 January 2025, including the link to Oliver’s article.

Incidentally, Oliver’s essay is so important that I will merge it, after the sixth instalment, into a single PDF to be accessed in the featured post, ‘The Wall’. But as I no longer want to edit that article, I will upload ‘The Wall’ again on 1 January 2025, including the link to Oliver’s article.

It is impressive that the viewpoint of The West’s Darkest Hour has existed for decades in the US but that very few have picked up the torch that Oliver left lying on the ground (National Alliance has published Oliver’s essay in its entirety, which I will only complete on this site until tomorrow).

A religion for sheep, 5

by Revilo P. Oliver

Published by Liberty Bell Publications in 1980,

under Oliver’s nom de guerre Ralph Perier.

All this, and hell too!

Christians like to prate about how much their bundle of irreconcilable superstitions has done for us. Well, it first gave our race schizophrenia and has now given it a suicidal mania.

It was bad enough when the Christians were under the spell of the Zoroastrian notion that the biological reality of race can be charmed away by a kind of magic called “conversion.” They hired missionaries to pester everyone else in the world, from the highly civilised Chinese to the uncivilisable anthropoids in Africa. They believed that the aliens could be transformed into the equivalent of White Europeans, if they were dunked in holy water by a licensed practitioner. For the dunking, the Ersatz-Christians substitute “education,” which they think a much more powerful kind of magic. But from this silly idea we have now progressed to a more baneful kind of unreason.

The Buddhist notion of equality, perverted by proletarian malice and festering envy, has become the fanatical faith of 95% of our race today. In a recent article, R.P. Oliver observed that our “intellectuals,” who disdain the Christian fairy tales about Jesus and preen themselves on being atheists or, at least, agnostics, nevertheless “cling to the morbid hatred of superiority that makes Christians dote on whatever is lowly, inferior, irrational, debased, deformed, and degenerate.” [like trans people, who weren't yet revered in Oliver's time. — Editor]. Both groups hold frantically to the dogma of the “equality of all races” (except, of course, the vastly superior race of the “Old Testament”), and equally believe that moral excellence is evinced by faith in what daily experience shows to be patently preposterous. And when they can no longer close their eyes to shut out the real world, they have a solution. The various races (except God’s People) must be made equal, must be reduced to the lowest common denominator of anthropoids.

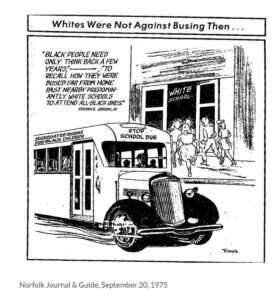

And so we come to the breathtaking transvaluation that is the dominant creed of our time: the Aryans, by virtue of the superiority they have shown in the past, are a vastly inferior race. They are burdened by the horrible guilt of not having committed suicide, a guilt they can expiate only by taxing themselves to hire their enemies to destroy them [emphasis in this post added by Editor]. They must love their enemies, but hate their own children. Especially in once-great Britain and the United States, the crazed Whites are not only subsidising the proliferation of their vermin and legislating to inhibit the reproduction of their own kind, but are importing from all the world hordes of their biological enemies to destroy their posterity.

Especially in the United States, they condemn their own children to the most degrading association with savages in their “integrated” schools. American parents evidently feel a “spiritual” satisfaction when their own children—or, at least, their neighbours’ children—are beaten, raped, and mutilated by the sub-humans. And British parents, who, if still prosperous, can protect their children from physical, though not from mental, squalour, abhor as wicked “racists” the few individuals who think their race is fit to survive. An honest psychiatrist (there are a few) could perhaps determine what weird mixture of sadism and masochism has been inculcated into the minds of our people.

Especially in the United States, they condemn their own children to the most degrading association with savages in their “integrated” schools. American parents evidently feel a “spiritual” satisfaction when their own children—or, at least, their neighbours’ children—are beaten, raped, and mutilated by the sub-humans. And British parents, who, if still prosperous, can protect their children from physical, though not from mental, squalour, abhor as wicked “racists” the few individuals who think their race is fit to survive. An honest psychiatrist (there are a few) could perhaps determine what weird mixture of sadism and masochism has been inculcated into the minds of our people.

Everywhere, the Christianised Aryans (including those who imagine they are not Christians) evidently agree that our race must be stamped out for the comfort and joy of the several mammalian species that covet our property and instinctively hate us.