exchange

Editor’s note: The following exchange between Alex Linder and Brad Griffin (a.k.a. Hunter Wallace) has been excerpted from a long thread on Vanguard News Network forum:

Brad Griffin said…

I don’t believe that Jews are 100% to blame for our situation. I believe there are many factors involved and that reducing it to the Jewish Question is simply an oversimplification of a complex process.

Alex Linder said…

“Main Jewish Cause” is accurate. “Single Jewish Cause” is a strawman.

VNN focused on jews for two reasons:

1) they are the powers that be, in 2012

2) they are the ones no one talks about

VNN has always mentioned the lesser causes of our racial decline, foremost of which is the jebus cult, which you conspicuously omit to blame at OD [Occidental Dissent]. Without abolitionism, no civil war. Without christianity, no abolitionism.

I have asked to no answer why the Catholic church is far more hostile to nazism than to communism.

Racial and christian worldviews are competitive, not complementary. Race offers a different and superior basis for society, and the church does not want white man to figure that out, as it briefly was under Hitler. The church prefers communism, because as bad as it is, it is temporary, since it runs against basic human nature, and will eventual disappear. Communism is such a repulsive and malignant jewish baby that even the ugly mexican baby of catholicism is appealing beside it. The key understanding is that there is nothing in the jebus cult that has any problem with the white race (or the South, for that matter) disappearing off the face of the earth. If there’s no doctrinal support for whites as whites, the doctrine is bad for us.

Originally Posted by Lew, for Alex:

What, exactly, do you hope to accomplish by attacking Christianity the way that you do? Who is your audience for these criticisms?

Audience is thinking adults. I hope to reduce respect for the cult in general by demonstrating its impotence and delusionality, the jew-obsequiousness of its leaders, and the functional anti-Whiteness of its doctrines. I would like to see the cult disappear among the white race. Christianity is criticized by jews for the wrong reasons, leading unthinking white men to think it must be basically good, just as WN foolishly assume same of Pat Buchanan because jews criticize him. Not so. The cult is a terrible thing—for reasons seldom given. I give those reasons, and I indicate how a race-firster were wise to treat the church, based on real-world evidence.

If a person is a WNist pagan or an atheist (like me), the person doesn’t need convincing Christian theology poses problems for racialists. If a person is a generic Christian, or a Christian with racial sympathies, and they do in fact exist, it doesn’t seem likely your critique will convince them to do anything different.

A christian with racial sympathies is confused and divided of mind, and needs the contradiction brought out so that he can decide which master to serve. And, by the way, as much ego as I use, I certainly don’t expect adult males to bow before me and proclaim me their leader; I expect the power and form of my delivery to put a little doubt behind their facade. And they can think it over privately away and safe from my mocking, which is, yes, quite vicious and harsh.

Related: why is attacking Christianity important when Jews hold much of the real power in society, and to the extent white gentiles hold significant power in society, they are almost all secular liberal egalitarians who reject Christianity?

Those secular liberal egalitarians are almost all christians, in fact. It’s important to attack christianity and conservatism because they are competitors for the minds and support we need for our cause. WN, coming from a Southern conservative background, have not understood this. This is why they freely mix these things. But that’s not what will work. We must distinguish and elevate our racial cause by attacking conservatives as our enemy, as I advocate in my essay elsewhere. Not by mixing with it and drowning ourself in it. We must be intolerant in order to rise, in order to gain the strength to defeat the main enemy—not mushy.

Smoothing over differences doesn’t work. It’s effeminacy. It allows our enemy, jews, to infiltrate and subvert us. It allows our enemy conservatives to steal our men and arguments and fundraising—without ever supporting our positions publicly (perfectly parallel to a girl you would fuck but not introduce to your parents). It creates a gauzy haziness that leaves just WTF we are unclear in the public mind, hence boring and shruggable.

Clarity, distinctions, principles, edges—all these things that are foreign to folks who think that everyone except the principled assholes like me can get along fine under a big tent. Macdonald is politically clueless. Greg Johnson is $$$-interested, and cuts his behavior by his prospects. Our new buddy Jethro [Brad Griffin] inhabits personalities like a hermit crab shells [emphasis added by Ed.]. These don’t get the job done. What does is shown by Golden Dawn, in Greece of all goddam places:

• real men under real names (99% of WN fall off)

• real men not afraid to name the jew and buck jew taboos (100% of conservatives)

• real men not afraid to fight in the street

• real men who spend their time and money helping their people in thousand ways, providing all kinds of services for free, out of love and duty and responsibility

Our situation, in America, is not as desperate as in Greece. So people aren’t looking so much for our leadership. But if they were tomorrow, we wouldn’t have anything prepared. And that’s to our shame, and for the reasons I indicate—we are unwilling to define who we are, and figure out the principles we will back under our real names with our real lives.

This is not a game, just because we treat it like one.

Whites prove by their behavior they support our basic position: they, South and North, want to live among other whites. And not be discriminated against because of their race. And not have the borders left open, and citizenship held cheap. And they want sexual normality, and just ordinary decency on tv, so you can actually watching something in the day or evening that you don’t cringe every fucking five seconds if your parents or grandparents are in the room.

Every fucking one of you knows exactly what I mean. This is the shit-kultur that jews have built—and we let them. And your goddam jesus dick suckers have had 2,000 years to get your shit in order, and you have fucking failed. You are a big plate of stewed cats anuses to me, perhaps tasty to some imagination-free slant-eyed third-shift Kia employee, but unfit for human consumption. Get the fuck out of the way, you fucking jebus nuthuggers. WE will clean up culture; you sad fags aren’t woman enough for the job. I figuratively piss on the grave of your imaginary jewish science-fiction hero.

Just listen to the tone of the MacDonald, Johnson and Parrott conversation. The first two are professionally deformed, per the French expression. Incapable of inciting passion in people by nature of the discipline their background has required of them. Parrott I think has an inkling.

I wish you fags who presume to doubt me would read the Golden Dawn thread, and watch some of the videos. That’s what’s going on in WN. It’s not some 90-yo jerkoff speaking in coded language to old ladies, it’s young men raising arms, flags, chants—roofs, as da niggers say. Figure it out. Jesus Christ, I am so fucking tired of being a remedial common sense teacher I could puke.

Brad Griffin said…

Here in the South, the Southern Baptist Convention was the last mainstream institution in the entire country to fall into line with the anti-white mainstream culture. They didn’t figure out that “racism” was a sin until the mid-1990s.

Linder conveniently ignores the fact “racism” was coined by European and Jewish atheists. He ignores the fact that the Soviet Union—which was officially atheist—pushed “racism” into the mainstream through its tentacles in world communism.

He ignores the fact that it was the secular universities, not the churches, where this nonsense got started in America. It was secular intellectuals like John Dewey who fell the hardest for it in the 1930s and 1940s and who made “racism” taboo in the aftermath of the Second World War.

After “anti-racism” had triumphed in the universities and among the intelligentsia in the 1930s and 1940s, then other mainstream institutions began to fall in line with the new consensus. Every single mainstream institution has been infected by this disease and the churches were among the most resistant but for some reason Linder blames the churches instead of the secular intellectuals who spearheaded the movement.

Here’s a reality check for Alex:

(1) You will never guess which state was the first to legalize gay marriage. It was Vermont which is the most secular, the most atheist, the least religious, and one of the least conservative states in America.

(2) The Jesus nuthuggers have gotten out of the way in the Northeast. They have gotten out of the way in Britain and Scandinavia. They certainly aren’t standing in the way in San Francisco.

And the result? It is precisely those places where cultural degeneracy has been taken to its greatest extreme. It is precisely those places where cultural degeneracy is called “progress,” not “worse is better.”

Does anyone know of an atheist country that is “pro-White”? The Soviet Union was officially atheist. Vermont is the least religious state in America. San Francisco is one of the least religious cities.

Alex is always picking on the British: in 2012, the British are thoroughly de-Christianized; in 1912, Britain was thoroughly Christian. Has the decline of Christ-Lunacy in the UK or Sweden or Norway over the past century produced a more racialist society? Is there anyone here who is excited about the prospects of racialism winning a mass following in San Francisco or Vermont?

Religion is a barrier that makes the Jew an outsider.

Alex Linder said…

One movement arose to restore white supremacy over a continent; the church opposed. I’m not sure what else you need to know. The top prelate in Greece has also condemned Golden Dawn in Greece.

The church, like the anti-white NWO socialists that spawned from it, is universalist, and universalism is inherently anti-white.

Brad Griffin said…

How so?

The church approved of slavery for centuries. The church approved of racialism for centuries.

Is there any historian who argues that Disraeli was anti-White? Every historian that I know of argues that Britain became more racialist after the 1850s.

Alex Linder said…

It became less elitist. In his novels he [Disraeli] wrote that blood is everything, and the world is ruled by a tiny minority behind the scenes, and in both instances he meant jews. Britain was already well into universalist fantasies at that point, and guess where those fantasies originated? In the sicko christ cult.

Christianity is liberalism. Or, as Spengler put it, christianity is the grandmother of bolshevism. Without christ-insanity, you wouldn’t have the progressive, secularist, communist garbage—the latter is simply an evolution of the former. They are both anti-white, and no different than the Republicans are from the Democrats.

Brad Griffin said…

That’s a stretch.

There is nothing in the Bible about natural rights. There is some talk in the Bible about equality in a purely spiritual otherworldly sense, but there is also talk about genocide and blood and soil and homophobia and patriarchy. The Bible explicitly endorses slavery.

The first thing that Jacobins did in France, who were inspired by the Enlightenment, was to behead King Louis XVI and overthrow the Gregorian Calendar and demonize the Church.

“Liberty” is the most important liberal value. Ron Paul is a liberal. Libertarianism is a species of liberalism.

Alex Linder said…

Originally posted by Griffin:

Ironically, it was also Oliver Cromwell who came up with the idea of the British as a superior “White” master race. There wasn’t much talk of “white supremacy” in Britain or Western Europe before Cromwell’s time.

Per E. Michael Jones, protestantism has always been very closely tied to jews. All these sub-cults imagine they are the real new jews. They’re idiots. Dangerous idiots.

The point is, British men came up with this idea of forcing everyone into their system. Everyone wants to be us. Everyone is jealous of us. One size fits all.

That’s why sane men have long observed, if it’s British or chrisitan, it’s usually a pretty lousy thing, and we don’t want it. Look at these creeps have made of the world, working hand in glove with the jew.

The only way out was indicated by NS, and the church you defend specifically, overtly and repeatedly denounced.

Christianity is the author of Europe’s decline. When the church goes, the racial animal will rebound. And that, I fervently hope, is what we are seeing harbinger of in Greece. From my lips to god’s ear that it will be the same in the US when the time comes.

Mississippi christian conservatism—nigger, please. You don’t produce Hitlers down there, you produce Shep Smiths.

Brad Griffin said…

Well, Christianity is pretty much dead in Britain and Scandinavia, and behold the result.

Alex Linder said…

Originally posted by Griffin:

Surely, you meant to say German supremacy, right?

No, not supremacy, merely leadership. Millions of Europeans understood what Hitler was doing, and felt it was needed and worth fighting for, even though they were not Germans.

Our point here is the church you’re defending did everything it could to destroy Hitler and undermine him. So for you to pose the idea the church is a defender of Europe’s racial health is unhistorical and ridiculous. Quote:

The church approved of slavery for centuries. The church approved of racialism for centuries. Salvation in the next world doesn’t imply racial equality in this world.

Slavery isn’t a pro-White institution. Whites have been enslaved many times. By jews and other muds.

The church’s universalism makes it anti-White. The fact it has not a single expressly pro-white doctrine or dogma makes it inherently anti-white.

The fact is that from day one, what was new and original about the church was that it was for everybody—it cut across all racial and social lines. This is why I tell you that christianity is liberalism. When these progressives go off against the christians, it’s exactly like Republicans doing battle with democrats. A big sham. They agree on basics, and they’re both against white racial solidarity. They both envision a new world order. One will bring about pan-mixian nirvana by digging wells, fixing cleft palates and adoption; the other will bring it about by speech codes and hate crimes laws and drone bombings. They pursue the same agenda by different means and emphases.

The white cause is wholly different.

Brad Griffin said…

I’m not seeing this great opposition between Christianity and “the white cause” in the South considering how Christianity and racialism coexisted here for over three centuries.

Alex Linder said…

That’s because you mistake mere contemporaneity or correlation for causation, like most of your mental inferiors.

[Quoting Griffin:]

The Church dominated European culture when all this talk about “whiteness” got started in the first place.

The church never spoke a word in racial defense of Europe. The church is international. There are more non-white christians than white christians. In light of that fact, it is ridiculous to say the church is a pro-white institution. It’s a universalist delusion factory. One of the three ugly desert sisters, as has been said.

Brad Griffin said…

Fifty years after he first started doing work for the magazine, Norman Rockwell was tired of doing the same sweet views of America for the Saturday Evening Post in the early 1960s. The great illustrator was increasingly influenced by his close friends and loved ones to look at some of the problems that was afflicting American society. Rockwell had formed close friendships with Erik Erickson and Robert Coles, psychiatrists specializing in the treatment of children and both were advocates of the civil rights movement.

His most profound influence was his third wife, Mary L. “Molly” Punderson, who was an ardent liberal and who urged him in new directions. On December 14, 1963, Rockwell did his last cover for the Saturday Evening Post and he began working for Look magazine. Look magazine finally gave Norman Rockwell the opportunity to express his social concerns.

Rockwell’s first painting was The Problem We All Live With, one of his greatest paintings.

This painting depicts Ruby Bridges, the little girl who integrated the New Orleans school system in 1960, being escorted to her class by federal marshals in the face of hostile crowds. It’s a simple picture, the disembodied figures of 4 stiff suited men and the vulnerable yet defiant figure of a school age African American girl marching lockstep. To the right is a tomato staining a wall, obviously thrown at the girl but just missing. My eyes focus on the girl and her immaculate white, a contrast to the graffiti stained wall in the background. As a painting it’s a wonder with its composition conveying Rockwell’s message in a few simple figures.

This painting depicts Ruby Bridges, the little girl who integrated the New Orleans school system in 1960, being escorted to her class by federal marshals in the face of hostile crowds. It’s a simple picture, the disembodied figures of 4 stiff suited men and the vulnerable yet defiant figure of a school age African American girl marching lockstep. To the right is a tomato staining a wall, obviously thrown at the girl but just missing. My eyes focus on the girl and her immaculate white, a contrast to the graffiti stained wall in the background. As a painting it’s a wonder with its composition conveying Rockwell’s message in a few simple figures.

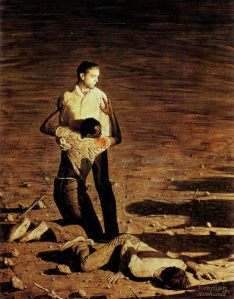

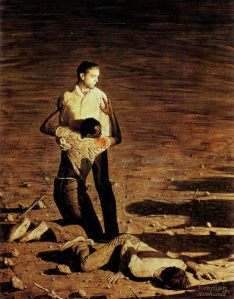

An even greater departure from Rockwell’s usual sweet America paintings is Southern Justice, painted in 1963. Rockwell did a finished painting, but the editors published Rockwell’s color study instead, and I think his color study conveys the terror of the scene more successfully.

An even greater departure from Rockwell’s usual sweet America paintings is Southern Justice, painted in 1963. Rockwell did a finished painting, but the editors published Rockwell’s color study instead, and I think his color study conveys the terror of the scene more successfully.

It depicts the deaths of three Civil Rights workers who were killed for their efforts to register African American voters. It is done in a monochrome sienna color, and it is a horrifying vision of racism. A look of it can be seen here.

Rockwell’s most optimistic view of the civil rights movement was Negro in the Suburbs, painted in 1967. It depicts an African American family moving into a white suburban neighborhood. The African American children look over by the kids in the neighborhood, with all the children sharing a love of baseball, America’s game. This painting can be found in this gallery.

In that painting, Norman Rockwell depicts an ideal, all-American, high trust, happily integrated neighborhood, which is the polar opposite of the integrated neighborhoods that actually exist.

You could turn on CNN or The Weather Channel or watch any movie in Black Run America (BRA) and you will find the same sort of disingenuous nonsense that Norman Rockwell was peddling in the 1960s.

Alex Linder said…

All I see is how easily christian motifs of the sliced savior turn into “civil rights” morality plays and paintings.