by Laurent Guyénot

The Jesus question: How fake is the Good News?

I regard Barbiero’s book as a fruitful attempt to solve the mystery of how the Jews created Christianity and made it the Roman religion. But it certainly doesn’t give the full story. Much happened in the next three centuries that needs to be clarified. One important context, which is seldom considered, is the ‘Crisis of the Third Century’ (235-284), during which ‘the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressures of barbarian invasions and migrations into the Roman territory, civil wars, peasant rebellions, political instability’ (Wikipedia), but also cataclysmic events and widespread diseases such as the Plague of Cyprian (c. 249-262), that was said to kill up to 5,000 people a day in Rome.[22] In such a context, the apocalyptic flavor of early Christianity must have been a key factor of its success. Interestingly, the apocalyptic Book of Revelation, the latest included into the Christian canon, is considered by some scholars to be a Christianized edition of a Jewish apocalypse, because, except for its prologue and epilogue (from 4:1 to 22:15), it contains no recognizable Christian motif.[23]

There are also two important building blocks of Christianity that Barbiero’s focus on Roman Mithraism leaves out: the Gospels’ life of Jesus, and Paul’s mystical Christ. How did they originate, and how were they integrated? The connection between them is one of the most difficult problems concerning the birth of Christianity. For, as Earl Doherty writes in The Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity begin with a mythical Christ? (1999), a book that has sent a shockwave in Jesus scholarship (here quoted from this 600-page pdf): ‘Not once does Paul or any other first century epistle writer identify their divine Christ Jesus with the recent historical man known from the Gospels. Nor do they attribute the ethical teachings they put forward to such a man.’ Christ is simply for Paul a celestial deity who has endured an ordeal of incarnation, death, burial and resurrection, and who communicates to his devotees through dreams, visions and prophecies. Such gnostic Christology has roots in mystery religions long predating Jesus. It is difficult to explain how a human Jesus could be transformed into such a divine Christ in a few decades, during the lifetime of those who knew him.

The first difficulty is that the vast majority of the earliest Christians were, of course, Jews. ‘God is One,’ says the most fundamental of Jewish theological tenets. Moreover, the Jewish mind had an obsession against associating anything human with God. He could not be represented by even the suggestion of a human image, and Jews in their thousands had bared their necks before Pilate’s swords simply to protest against the mounting of military standards bearing Caesar’s image within sight of the Temple. The idea that a man was a literal part of God would have been met by any Jew with horror and apoplexy.

And yet we are to believe that Jews were immediately led to elevate Jesus of Nazareth to divine levels unprecedented in the entire history of human religion. We are to believe not only that they identified a crucified criminal with the ancient God of Abraham, but that they went about the empire and practically overnight converted huge numbers of other Jews to the same outrageous—and thoroughly blasphemous—proposition. Within a handful of years of Jesus’ supposed death, we know of Christian communities in many major cities of the empire, all presumably having accepted that a man they had never met, crucified as a political rebel on a hill outside Jerusalem, had risen from the dead and was in fact the pre-existent Son of God, creator, sustainer, and redeemer of the world. Since many of the Christian communities Paul worked in existed before he got there, and since Paul’s letters do not support the picture Acts paints of intense missionary activity on the part of the Jerusalem group around Peter and James, history does not record who performed this astounding feat.[24]

The simplest way to overcome this difficulty is to assume that the transformation of the human Jesus into the cosmic Christ (or the other way round, as Doherty suggests) didn’t happen spontaneously, but was engineered by connecting several elements, with the aim of fabricating a Judeo-Hellenistic syncretic religion.

Paul’s letters were first collected in the first half of the second century by Marcion of Sinope who also included in his canon a short evangelion (he was the first to use the term), but rejected the Jewish Tanakh. Around 208, Tertullian, a Carthaginian of probable Jewish origin, complained that ‘the heretical tradition of Marcion filled the universe’ (Against Marcion v, 19). He also tells us that, during the time of Marcion, another Gnostic teacher named Valentinus almost became bishop of Rome. In the third century AD appeared the Persian Mani, who called himself ‘apostle of Jesus Christ,’ but rejected any Jewish influence. Manicheans became the label pinned by the Catholic Church on all the Gnostic movements that came from the East, such as the Paulicians from Anatolia in the eighth century, or the Bogomils from Bulgaria in the ninth century, the ancestors of the Cathars who were eradicated from the south of France in the early thirteenth century. All these movements, which can be seen as successive waves of the same movement, venerated Paul and rejected the Torah, whose god they regarded either as an evil demiurge, a deceptive demon, or a malicious fiction.

In the fourth century, Gnostic Christianity was still alive and flourishing. The monastic library of the Egyptian Brotherhood of Saint Pachomius, the first known Christian monastery, contained a great wealth of Gnostic literature (including the Gospel of Thomas), amid Platonic, Hermetic, and Zoroastrian books. As New Testament scholar Robert Price tells in his fascinating book Deconstructing Jesus (2000):

Apparently when the monks received the Easter Letter from Athanasius in 367 C.E., which contains the first known listing of the canonical twenty-seven New Testament books, warning the faithful to read no others, the brethren must have decided to hide their cherished ‘heretical’ gospels, lest they fall into the hands of the ecclesiastical book burners.[25]

All these codices were hidden in a graveyard at Nag Hammadi, where they were discovered in 1945, revolutionizing our image of early Christianity. Scholars have since started to question the traditional view of Gnostics as dissenters who broke away from the Orthodox Church; rather, the Gnostics who never ceased claiming that Roman Catholics were corrupting the Gospel under Jewish influence, may have been right all along.

As I started delving into these questions, I discovered that a new school of New Testament exegesis, pioneered by Earl Doherty’s Jesus Puzzle, claims that Christianity was born in myth, not in history. I had always assumed that Jesus’ biography was too historically plausible to be a fiction. In my thirties, I had become fascinated by the quest for the historical Jesus and wrote a book on the ‘legendary’ relationship between Jesus and John the Baptist, which argued that the Gospel writers falsified the genuine prophecies of John, and forged spurious praises of Jesus by John, and that much of the sayings attributed to Jesus (from the hypothetical Q document) were originally attributed to John.[26] Nevertheless, I didn’t doubt the historicity of Jesus. But my recent journey into the ‘Christ Myth’ theory has convinced me that the historical Jesus is more elusive than I thought. The Gospels, for one thing, are not as old as generally admitted (between the 70s and the 90s), for, as Doherty points out:

Only in Justin Martyr, writing in the 150s, do we find the first identifiable quotations from some of the Gospels, though he calls them simply ‘memoirs of the Apostles,’ with no names. And those quotations usually do not agree with the texts of the canonical versions we now have, showing that such documents were still undergoing evolution and revision.[27]

A late second-century date for the first narrative about Jesus is consistent with the hypothesis—that goes contrary to Barbiero’s theory—that Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews originally contained a reference to John the Baptist and one to James the Just, but no reference to Jesus, who was later inserted between the two so that John could be presented as Jesus’ precursor and James as his brother and heir. There is much evidence that James, like John the Baptist before him, was a famous figure in his own right. According to biblical scholar Robert Eisenman, author of James, the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls, James is identical to ‘the Teacher of Righteousness’ mentioned in some of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which have been dated too early. Strangely,

The person of James is almost diametrically opposed to the Jesus of Scripture and our ordinary understanding of him. Whereas the Jesus of Scripture is anti-nationalist, cosmopolitan, antinomian—that is, against the direct application of Jewish Law—and accepting foreigners and other persons of perceived impurities, the Historical James will turn out to be zealous for the Law, and rejecting of foreigners and polluted persons generally.

His death by stoning in 62 ‘was connected in popular imagination with the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE in a way that Jesus’ death some four decades before could not have been.’

Variant manuscripts of the works of Josephus, reported by Church fathers like Origen, Eusebius and Jerome, all of whom at one time or another spent time in Palestine, contain materials associating the fall of Jerusalem with the death of James—not with the death of Jesus. Their shrill protests, particularly Origen’s and Eusebius’, have probably not a little to do with the disappearance of this passage from all manuscripts of the Jewish War that have come down to us.[28]

Jesus scholars of the ‘mythicist’ school—by opposition to ‘historicist’—refrain from expressing their conclusion in conspiratorial terms. In his book On the Historicity of Jesus, Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt, Richard Carrier writes: ‘the Jesus we know originated as a mythical character,’ and only ‘later, this myth was mistaken for history (or deliberately repackaged that way).’ But I find ‘mistaken’ very unlikely, and ‘deliberately repackaged’ much more probable. Carrier actually suggests that the fundamental structure of the narrative was borrowed from a well-established Roman mythical pattern:

In Plutarch’s biography of Romulus, the founder of Rome, we are told he was the son of god, born of a lowly shepherd; then as a man he becomes beloved by the people, hailed as king, and killed by the conniving elite; then he rises from the dead, appears to a friend to tell the good news to his people, and ascends to heaven to rule from on high. Just like Jesus.

Plutarch also tells us about annual public ceremonies that were still being performed, which celebrated the day Romulus ascended to heaven. The sacred story told at this event went basically as follows: at the end of his life, amid rumors he was murdered by a conspiracy of the Senate (just as Jesus was ‘murdered’ by a conspiracy of the Jews—in fact by the Sanhedrin, the Jewish equivalent of the Senate), the sun went dark (just as it did when Jesus died), and Romulus’s body vanished (just as Jesus’ did). The people wanted to search for him but the Senate told them not to, ‘for he had risen to join the gods’ (much as a mysterious young man tells the women in Mark’s Gospel). Most went away happy, hoping for good things from their new god, but ‘some doubted’ (just as all later Gospels say of Jesus: Mt 28.17; Lk 24.11; Jn 20.24-25; even Mk 16.8 implies this). Soon after, Proculus, a close friend of Romulus, reported that he met Romulus ‘on the road’ between Rome and a nearby town and asked him, ‘Why have you abandoned us?’, to which Romulus replied that he had been a god all along but had come down to earth and become incarnate to establish a great kingdom, and now had to return to his home in heaven (pretty much as happens to Cleopas in Lk 24.13-32). Then Romulus told his friend to tell the Romans that if they are virtuous they will have all worldly power.

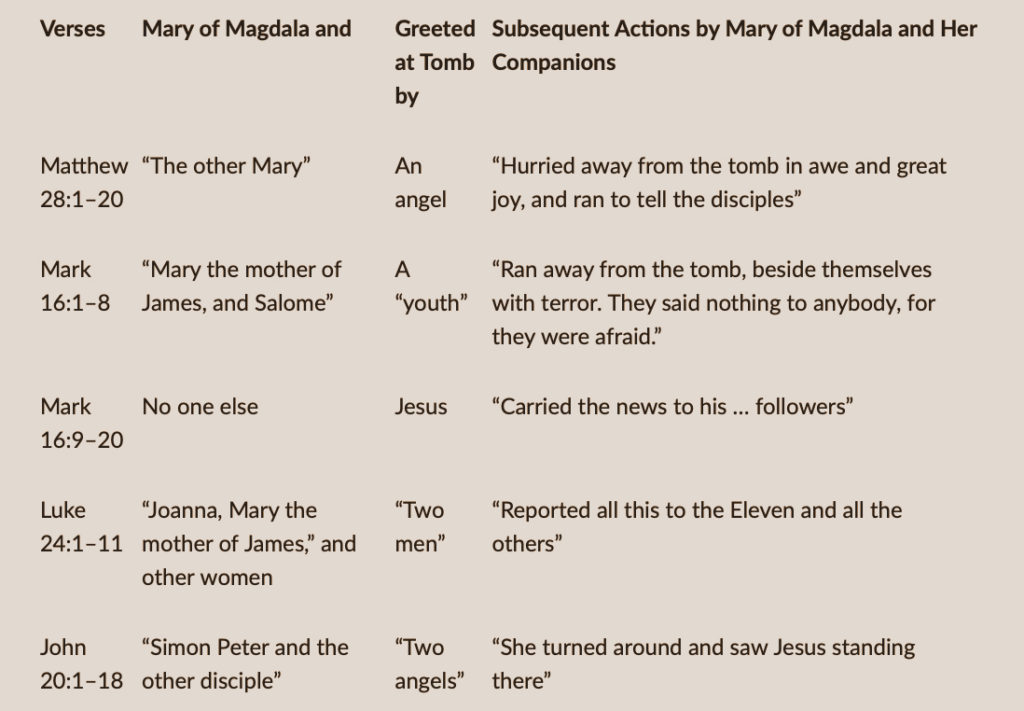

Livy’s account [History 1.16], just like Mark’s, emphasizes that ‘fear and bereavement’ kept the people ‘silent for a long time’, and only later did they proclaim Romulus ‘God, Son of God, King, and Father’, thus matching Mark’s ‘they said nothing to anyone’, yet obviously assuming that somehow word got out.

It certainly seems as if Mark is fashioning Jesus into the new Romulus, with a new, superior message, establishing a new, superior kingdom. This Romulan tale looks a lot like a skeletal model for the passion narrative: a great man, founder of a great kingdom, despite coming from lowly origins and of suspect parentage, is actually an incarnated son of god, but dies as a result of a conspiracy of the ruling council, then a darkness covers the land at his death and his body vanishes, at which those who followed him flee in fear (just like the Gospel women, Mk 16.8; and men, Mk 14.50-52), and like them, too, we look for his body but are told he is not here, he has risen; and some doubt, but then the risen god ‘appears’ to select followers to deliver his gospel.

There are many differences in the two stories, surely. But the similarities are too numerous to be a coincidence—and the differences are likely deliberate. For instance, Romulus’s material kingdom favoring the mighty is transformed into a spiritual one favoring the humble. It certainly looks like the Christian passion narrative is an intentional transvaluation of the Roman Empire’s ceremony of their own founding savior’s incarnation, death and resurrection. Other elements have been added to the Gospels—the story heavily Judaized, and many other symbols and motifs pulled in to transform it—and the narrative has been modified, in structure and content, to suit the Christians’ own moral and spiritual agenda. But the basic structure is not original.[29]

Other scholars have long identified strong parallels between the life of Jesus and the legendary lives of holy men such as Pythagoras or Appolonius of Tyana. In the later, for example, we find that Appolonius, after a lifetime of doing miracles, healing the sick, casting out demons, and raising the dead, was delivered by his enemies to the Roman authorities. ‘Still,’ according to Bart D. Ehrman’s summary, ‘after he left this world, he returned to meet his followers in order to convince them that he was not really dead but lived on in the heavenly realm.’[30]

Robert Price has pointed another likely source for the Gospel narratives: Greek novels such as Chariton’s Chaereas and Callirhoe, Xenophon’s Ephesian Tale, Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon, Heliodorus’ Ethiopian Story, Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe, The Story of Apollonius, King of Tyre, Iamblichus’ Babylonian Story, and Petronius’ Satyricon.

Three major plot devices recur like clockwork in the ancient novels, which were usually about the adventures of star-crossed lovers, somewhat like modern soap operas. First, the heroine, a princess, collapses into a coma and is taken for dead. Prematurely buried, she awakens later in the darkness of the tomb. Ironically, she is discovered in the nick of time by grave robbers who have broken into the opulent mausoleum, looking for rich funerary tokens […]. The crooks save her life but also kidnap her, since they can’t afford to leave a witness behind. When her fiancé or husband comes to the tomb to mourn, he is stunned to find the tomb empty and first guesses that his beloved has been taken up to heaven because the gods envied her beauty. In one tale, the man sees the shroud left behind, just as in John 20:6-7.

The second stock plot device is that the hero, finally realizing what has happened, goes in search of the heroine and eventually runs afoul of a governor or king who wants her and, to get him out of the way, has the hero crucified. Of course, the hero always manages to get a last-minute pardon, even once affixed to the cross, or he survives crucifixion by some stroke of luck. Sometimes the heroine, too, appears to have been killed but winds up alive after all.

Third, we eventually have a joyous reunion of the two lovers, each of whom has despaired of ever seeing the other again. They at first cannot believe they are not seeing a ghost come to comfort them. Finally, disbelieving for joy, they are convinced that their loved one has survived in the flesh.

As I have noted in my article ‘The Crucifixion of the Goddess,’ the love romance pattern is still apparent in the Gospel, where the risen Jesus appears first to his longtime follower Mary Magdalene, who, perhaps for that reason, was regarded as Jesus’ soul mate by many Gnostics.[31]

Price quotes the following passage from Chariton’s Chaereas and Callirhoe, where Chaereas discovers the empty tomb of his beloved:

When he reached the tomb, he found that the stones had been moved and the entrance was open. [Cf. John 20:1] He was astonished at the sight and overcome by fearful perplexity at what had happened. [Cf. Mark 16:5] Rumor—a swift messenger—told the Syracusans this amazing news. They all quickly crowded round the tomb, but no one dared go inside until Hermocrates gave an order to do so. [Cf. John 20:4-6] The man who went in reported the whole situation accurately. [Cf. John 19:35; 21:24] It seemed incredible that even the corpse was not lying there. Then Chaereas himself determined to go in, in his desire to see Callirhoe again even dead; but though he hunted through the tomb, he could find nothing. Many people could not believe it and went in after him. They were all seized by helplessness. One of those standing there said, ‘The funeral offerings have been carried off [Cartlidge’s translation reads: ‘The shroud has been stripped off’—cf. John 20:6-7]—it is tomb robbers who have done that; but what about the corpse—where is it?’ Many different suggestions circulated in the crowd. Chaereas looked towards the heavens, stretched up his arms, and cried: ‘Which of the gods is it, then, who has become my rival in love and carried off Callirhoe and is now keeping her with him…?’

Later on, Callirhoe, reflecting on her vicissitudes, says, ‘I have died and come to life again.’ Later still, she laments, ‘I have died and been buried; I have been stolen from my tomb.’ In the meantime, poor Chaereas is condemned to the cross, which he has to carry himself. But in the last minute, just before being nailed, his sentence is commuted, and he is taken down from the cross. Here, then, comments Price, is a hero who went to the cross for his beloved and returned alive. In the same story, a villain is likewise crucified, though since he is gaining his just deserts, he is not reprieved. This is Theron, the pirate who carried poor Callirhoe into slavery. He was crucified in front of Callirhoe’s tomb.

Did some Jews, by some concerted and persistent Hasbara, brainwash the Romans with an unbelievable Jewish tale plagiarized from Greek novels, Roman myths, and Mithraic cult? Surely there are other ways to look at Christianity than as a Jewish trick. But I find the hypothesis worth considering. I hear on this webzine [Editor's Note: The Unz Review] a lot of complaint against Jewish cultural colonization. I am merely suggesting that it didn’t start yesterday.

________________

[22] Kyle Harper, The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, Princeton UP, 2017.

[23] See for example James Charlesworth, Jesus within Judaism, SPCK, 1989.

[24] Earl Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle: Was There no Historical Jesus? on this 600-page pdf, pp. 33 and 16.

[25] Robert Price, Deconstructing Jesus, Prometheus Book, 2000, archive.org, pp. 44-45.

[26] Recent scholars arguing along those lines include Karl H. Kraeling, John the Baptist, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1951; Charles H. H. Scobie, John the Baptist, Fortress Press, 1964; W. Barnes Tatum, John the Baptist and Jesus: A Report of the Jesus Seminar, Polebridge Press, 1994; Joan Taylor, The Immerser: John the Baptist within Second Temple Judaism, Wm B. Eerdmans, 1996; Robert L. Webb, John the Baptizer and Prophet: A Socio-Historical Study, Sheffield Academic Press, 1991; Walter Wink, John the Baptist in the Gospel Tradition, Cambridge UP, 1968.

[27] Earl Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle, op. cit., p. 52 .

[28] Robert Eisenman, James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Viking Penguin, 1996.

[29] Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus, Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt, Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014, p. 56.

[30] Bart D. Ehrman Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth, HarperCollins, USA. 2012, p. 208, quoted from Wikipedia.

[31] Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979.

Those properly comprehending, yet prone to resist the present thesis then must answer: How might a Judaized, Christianized adaptation of the “translation fable,” particularly one mimetically following that of Romulus, have appeared, if not more or less precisely as one finds crafted in the postmortem narratives of the New Testament Gospels? [page 177]