The Rockwell years (1959-1967)

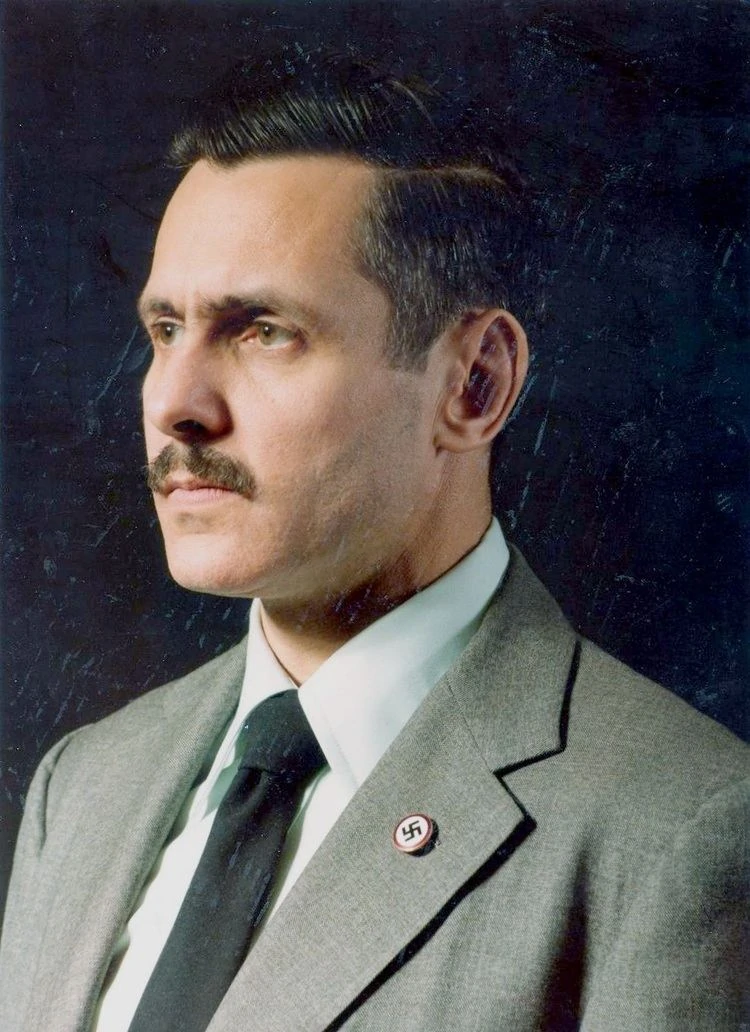

When discussing Movement history, the period 1959-1967 is commonly referred to as ‘The Rockwell Years’, and rightly so. George Lincoln Rockwell first raised the Swastika banner in Arlington, Virginia, on March 8, 1959, and he was assassinated there on August 25, 1967. There were indeed other NS and pro-NS organizations on the scene during these years. Some of these were older than Rockwell’s party, such as the National States Rights Party and the National Renaissance Party, which we have previously discussed. Others arose as splinters or rivals of Rockwell’s movement, such as the White Party of America and the American National Party. For their part, the NSRP and the White Party were larger than Rockwell’s American Nazi Party.

But it is Rockwell who dominated the scene in every sense: he led the way in public awareness of the Movement, and forged a new path in the theoretical development of National Socialism. Abroad, he provided the initiative for the formation of the World Union of National Socialists and at home, he set a precedent for mass NS action with the Chicago White people’s rebellion of 1966. While his competitors in the pro-White movement laboured in obscurity, Rockwell was a household name. And everywhere his dynamic personality was felt: he was the standard against which other leaders and organizations were judged.

Getting started

In terms of resources and manpower, Rockwell started from zero; he was alone, without even the comfort of his wife and children. The lease would soon expire in the house in which he lived, and the small offset printing press in the basement would also be taken away from him at that time. The political contacts he had in the pro-White movement were scattered across the country, and for the most part, they were already committed to various mini-parties and were not looking for something new. Financially, he was broke. But what he lacked externally he more than made up for with his internal resources: in courage, intellect, imagination and drive.

He hung the huge Swastika banner on his living room wall. The house / headquarters was located on a busy street, and the flag was visible through a picture window to passing motorists and pedestrians. He opened his doors to the curious, and he spent every evening in discussion and debate with those who showed up. Word of the anti-Jewish naval commander with the Swastika flag on his wall spread quickly, and within a few weeks, Rockwell had his first followers. Newspaper publicity followed, and the Rockwell movement was born.

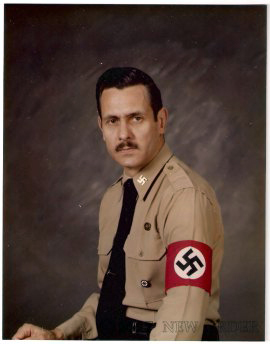

The name he chose for the new party was long and cumbersome. He called it, the ‘American Party of the World Union of Free Enterprise National Socialists’. The ‘American Party’ was the name of a nativist political party of the 19th century, which espoused a sort of proto-racial nationalist ideology. The term ‘Free Enterprise’ was a reflection of Rockwell’s initial unease with the socialist component in National Socialism. Those whom he first recruited almost uniformly came from what the media called the ‘far-right’ in which ‘socialism’ is a dirty word. Rockwell designed a basic khaki uniform for his members, similar to the US class A naval uniform. A Swastika armband was worn on the left arm. A Rockwell innovation was to place a small blue circle in the centre of the Swastika. This symbolized the globe, and thereby the international character of Rockwell’s racialism. Almost immediately, the initial name of the party was shortened to simply the ‘American Nazi Party’. This is the designation by which it would be known throughout Rockwell’s lifetime, and by which American National Socialism is still known today in the popular mind.

Rockwell’s strategic plan

Rockwell had spent his entire adult life in the US navy. He had served in World War II and the Korean War. For a time, he was on the staff of the US Naval Mission to Brazil. Consequently, he knew something about military operations and strategic planning. Unlike many movement leaders, who charge off blindly into the political arena with little or no idea of what they are doing, Rockwell had a plan.

He called it the ‘Four Phase Plan’, and it was designed to take Rockwell and the ANP from complete obscurity and impotence on the utmost fringes of the American political spectrum, to the White House. Here are the four phases:

PHASE ONE: Through agitation of all sorts, make the ANP a household name known to every White American. Rockwell was aware that racial nationalist formations were routinely ignored by the mass media. Consequently, they and their programs were completely unknown to the general population. But, he correctly surmised, by proclaiming himself to be an open ‘Nazi’ complete with Swastikas, praise for Adolf Hitler and a program that included gas chambers for ‘Jew traitors’, he could craft a public image so outrageous that the media could not ignore him. He would force the Jewish-controlled media to give him the publicity he desired, despite themselves. The downsides of this approach were two-fold: (1) The image that he projected to the public was not one of serious National Socialism, but rather an exaggerated caricature or cartoon version of the real thing; and (2) The publicity that the Party received was always hostile, to the point that it distorted Rockwell’s message even further.

PHASE TWO: Education. Once he had attracted the attention of the general public, he would correct the false image of National Socialism that had been projected to them and instead educate them as to the true nature and belief system of the NS worldview.

PHASE THREE: Organization. Once he had an educated cadre of trained party leaders and a base of support among the population, he would organize the White masses into what he termed a ‘powerful political machine’.

PHASE FOUR: The ultimate phase of Rockwell’s plan was to use the White, NS political machine that he had built to take national power.

He always spoke of taking power legally, through elections. However, as a political realist, he privately conceded that he would use whatever means necessary to secure the existence of the White race: no options were off the table.

Anyone wishing to examine Rockwell’s Four-Phase Plan in further detail should consult the last chapter of his political autobiography, This Time the World (1962), in which he explicates it in depth (pages 416-422 in the standard edition).

Rockwell discussed the plan frequently and publicly. This was a calculated risk on his part: normally, one does not divulge one’s plans to the enemy but instead keeps them secret. By making his plan public, he sought to reassure the authorities (especially the FBI) that he was not seeking to subvert and overthrow the government by force, which is illegal, but instead was seeking to make changes in a legal and peaceful manner. At the same time, he was trying to explain the disreputable and outrageous nature of his propaganda to serious-minded potential recruits who might otherwise be put off by the vulgar language, provocative street theatre and talk of gas chambers.

Phase One operations

In the last nine months of his life, Rockwell began to transition the party from Phase One to Phase Two. But for the preceding eight years he had been pushing Phase One as hard as he could, and so it is Phase One activities and propaganda for which he is best remembered.

This included street theatre, in which a handful of uniformed stormtroopers (usually between a half-dozen and a dozen) would march or picket. In addition to displaying the Swastika, they would carry deliberately provocative signs, such as ‘Who Needs Niggers?’, ‘Gas Jew-Communist Traitors’ and ‘Back to Africa’. The sole goal was to draw publicity to the party. Sometimes there would be a fight and arrests. So much the better, Rockwell reasoned, for that would guarantee the notoriety he sought. When he was allowed to present his ideas to a mass audience, as in his famous 1966 interview in Playboy magazine, he would consciously make himself out to be thuggish and buffoonish: he knew if he came across as too sharp and too persuasive, such interviews would never see the light of day.

ANP printed material was likewise designed to be outrageous. Towards the end of Phase One, he wrote: ‘When I began, I purposely made my propaganda as brutal and shockingly rough as I could, simply to force attention. And I have kept everlastingly at the business of building a simple and direct image of all-out hostility to “Jews and niggers” in the minds of millions of Americans, regardless of the costs in other respects’.

The important thing to remember about this approach is that it was a deliberate tactic, crafted to force a hostile news media to give him publicity–any publicity–which he described as ‘the lifeblood of any political movement’. He knew that what he was doing was not a reflection of serious National Socialism; it was a temporary expedient that he intended to abandon as soon as it had achieved its goal of making George Lincoln Rockwell and the ANP household names.

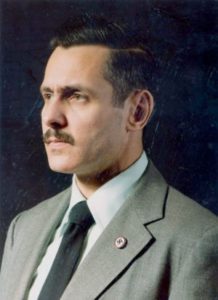

Proof of concept: the advent of William Pierce

Throughout his career, Rockwell spoke to many dozens of audiences at colleges and universities. This was an activity that fell into the Phase Two category–education–rather than Phase One. On these occasions, Rockwell could speak directly to the people he wanted to reach; he was not dependent on the media or any other third party. Consequently, he could explain National Socialism to his audience straightforwardly and seriously, without the outrageous slogans and provocative regalia that accompanied ANP street demonstrations. Another benefit of a speaking engagement is that the institution would pay Rockwell an honorarium of a few hundred dollars. The ANP operated on a month-to-month, shoe-string budget, with the staff at the Arlington headquarters were sometimes reduced to a near-starvation diet. The income from the colleges helped keep the party afloat financially.

One such speaking engagement took place at San Diego State College in California, on March 8, 1962. Rockwell, dressed in a suit and tie, spoke respectfully to an audience of some 3,000 students, explaining to them the ANP and its platform. Partway through his presentation, a Jewish student bolted from his seat and jumped up on the stage, attempting to wrest the microphone from Rockwell. Rockwell pushed him away, and as he squared off to fight with the attacker, the Jew punched him twice in the face, breaking his sunglasses. Before Rockwell could respond, two of his security men tackled the Jew from behind and threw him to the ground, pummeling him into submission. Other troublemakers in the audience then jumped up and began shouting, and the rest of Rockwell’s talk was cancelled.

On the surface, it appeared as though his enemies had won that round: they kept Rockwell from speaking. But the Jews had unwittingly played right into his hands. The fracas generated nationwide media coverage for Rockwell. One of those who saw the news reports was Dr William L. Pierce, a 29-year-old physics professor at Oregon State University. The report he saw on the evening news of the debacle in San Diego did not tell him much of what Rockwell had to say, but it gave him enough details that Pierce was intrigued. He dug out the ANP mailing address from a book at the school library and wrote Rockwell a letter.

The two men began corresponding, and in 1964 Pierce left his teaching position and moved across the country to help Rockwell out. This was proof of concept for at least part of Rockwell’s plan: the publicity that he received attracted the attention of a like-minded person of quality who recognized that Rockwell had a serious message to convey, even if his public image was disreputable and semi-comedic.

Pierce was a brilliant man with great moral courage, and in the years and decades to come, he would play a major role in the development of the Movement in the US. His service with Rockwell as a young man was a sort of basic training for him. Pierce never formally joined the ANP, although Rockwell asked him to sign up on several occasions and offered him an officer’s commission in the organization. One problem was that Rockwell insisted that if he were to join, that he would have to participate in at least one or two stormtrooper demonstrations each year. ‘Otherwise’, Rockwell explained, ‘the men will not respect you’. But demonstrations and the whole ‘Nazi’ image were not in keeping with Pierce’s outlook and personality, and so he declined to join. In the short term, this hobbled his Movement career. But the absence of news photographs showing Pierce parading in a ‘Nazi’ uniform meant that doors would be open to him in the years ahead that would not have been open had such photos existed.

Pierce was a brilliant man with great moral courage, and in the years and decades to come, he would play a major role in the development of the Movement in the US. His service with Rockwell as a young man was a sort of basic training for him. Pierce never formally joined the ANP, although Rockwell asked him to sign up on several occasions and offered him an officer’s commission in the organization. One problem was that Rockwell insisted that if he were to join, that he would have to participate in at least one or two stormtrooper demonstrations each year. ‘Otherwise’, Rockwell explained, ‘the men will not respect you’. But demonstrations and the whole ‘Nazi’ image were not in keeping with Pierce’s outlook and personality, and so he declined to join. In the short term, this hobbled his Movement career. But the absence of news photographs showing Pierce parading in a ‘Nazi’ uniform meant that doors would be open to him in the years ahead that would not have been open had such photos existed.

Instead, he helped Rockwell in other ways, working on various low-key projects and advising him. In 1966, at his initiative and largely at his own expense, Pierce launched a theoretical journal for the ANP and its international affiliate, the World Union of National Socialists. It was entitled National Socialist World. The journal provided a platform for serious NS exposition on a high intellectual level. It gave a certain heft and gravitas to Rockwell’s movement that it had previously lacked. NS World included both translations of writings from the Third Reich era, and new, post-War material. Among the authors who wrote for it were, in addition to Rockwell himself, British NS leader Colin Jordan, Matt Koehl, Bruno Luedtke (a former Hitler Youth officer and NSDAP member) and Indo-European NS philosopher Savitri Devi. Pierce provided an editorial for each issue.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: This was the right path to go but, alas, Pierce stopped publishing National Socialist World the next year after the assassination of Rockwell.

______ 卐 ______

Development of NS theory under Rockwell

In addition to being a man of action, Rockwell was a serious thinker. During his university days, he had majored in philosophy. Rockwell studied Mein Kampf and other original NS materials. He realized that Hitler’s teachings regarding, Nature, Race, Society, Marxism and the Jews were fundamentally correct. At the same time, however, he saw that Hitler’s defeat in 1945 had changed the world forever. The geo-political realities that were obtained before the War had been permanently altered. Before the War, the perception in NS and related circles was that each Aryan nation was menaced internally by Jewish Capitalism, and externally by Soviet-based Jewish-Bolshevism. Accordingly, it was up to each separate Aryan folk or nation to defend itself, or, as Hitler put it, to ‘devise its form of national resurrection’.

In the post-1945 dispensation, Rockwell realized, this had changed. It was not the individual Aryan countries that were threatened, but rather the Aryan race as a whole that was under attack – and in danger of complete extinction. It was only logical, he reasoned, that a race-wide threat required a race-wide response. So, for Rockwell, the political focus was on race, with national concerns being secondary, whereas, in Hitler’s conception, the good of the nation came first.

Rockwell’s almost-exclusive focus on Race as the primary issue had the side effect of marginalizing almost all other NS concerns, especially in the social and economic spheres. The party program made good faith nods at economic theory and social reform, but such issues were never fleshed out, nor were they the focus of party outreach. Exacerbating this neglect was the fact that the ANP was considered – and considered itself – as a far-right organization. Among the right, efforts at social reform and economic justice were considered the purview of the left. The people Rockwell targeted and whom he attracted had little or no concern with such issues.

Another problem was that the confrontational racial nature of ANP outreach made it impossible on a practical level to build bridges to Black nationalists and other non-Whites who shared the National Socialist position on racial separation. Much has been written on Rockwell’s effort to forge a link with the Nation of Islam and other Black separatists, but in fact, nothing concrete was ever achieved on this front, although theoretically trans-racial alliances between National Socialists and non-Whites are certainly possible.

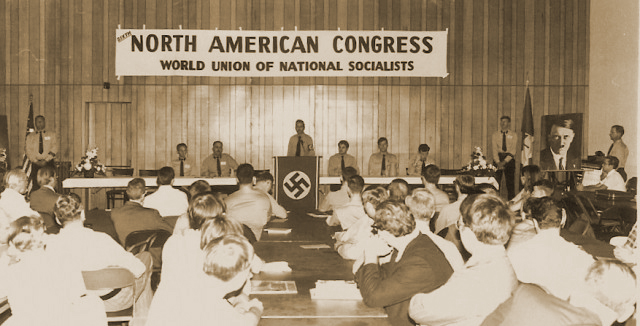

World Union of National Socialists

A practical manifestation of Rockwell’s promotion of National Socialism as an international pan-Aryan movement was the World Union of National Socialists. As previously noted, the concept of a ‘World Union’ was already present in his thinking when he founded his party in 1959 under the name ‘World Union of Free Enterprise National Socialists’. But for the first three years of the ANP such a formation was only an idea, not a political reality.

Rockwell’s ANP, however, inspired other National Socialists throughout the world to form similar parties. One of these was the National Socialist Movement, founded in Great Britain by Colin Jordan in April of 1962. In August of that year, Jordan and the NSM hosted a camp in the Cotswold region of England. It was attended by National Socialists from across the globe, including Rockwell.

Among those who participated, besides Rockwell and Jordan, were Bruno Luedtke from Germany, Savitri Devi, John Tyndall and Roland Kerr-Ritchie as well as delegates from Austria, Belgium and France. By the end of the gathering, the assembled comrades had agreed on a preliminary set of guidelines for the ‘World Union of National Socialists’ (Rockwell agreed to drop the term ‘Free Enterprise’ under pressure from the European comrades). The guidelines were known as the ‘Cotswold Agreements’. They named Colin Jordan as the International Leader, Rockwell as the Deputy International Leader, Karl Allen of the ANP as International Secretary, and John Tyndall of the NSM as Assistant International Secretary. The document stated that it was provisional, contingent on its ratification by a ‘World Nazi Congress’ scheduled for the next year.

The 1963 congress never took place. Jordan was imprisoned for political offences shortly after the gathering, and Rockwell became the International Leader. When Karl Allen left the ANP in 1964 after a failed mutiny, Matt Koehl become the International Secretary. The ‘provisional’ declaration, in effect, was made permanent.

The World Union provided for international strategic cooperation for its affiliated organizations (limited to one for each country), as well as participation by individual National Socialists in countries without a formal WUNS affiliate. Eventually, Jordan reorganized the NSM as the British Movement and withdrew from the World Union.

WUNS was never as effective in coordinating international NS operations as Rockwell had hoped. Eventually, after his death, it withered away until it was only a letterhead or symbolic organization. But it was important, nonetheless, for it established National Socialism in practice as a pan-Aryan internationalist movement, and not a movement embodying a racialist version of 19th-century petty nationalism.

The precedent of mass action in Chicago

Another precedent established by Rockwell was that of National Socialism as a mass movement for American Whites. In the summer of 1966, the west side of Chicago was rocked by a series of riots by working-class White ethnics who were opposed to the forced integration of their neighbourhoods. Spearheading the effort to break up all-White neighbourhoods was a young Jesse Jackson, who was soon joined by Martin Luther King.

The Whites felt abandoned by the politicians whom they had elected, and by the police, who were protecting Black ‘civil rights’ marchers invading their territory. The churches likewise sided with the Negroes. The media put out a steady stream of anti-White, pro-Black propaganda. Unsurprisingly, Chicago’s powerful Jewish community sided against the Whites. Special hatred was reserved by the White workers for the real estate agents – most of whom were Jews – who were trying through every means, openly and underhanded alike, to sell homes to Blacks in all-White neighbours. Everyone was against them. Who would stand up for the White Man?

The ANP maintained a small storefront office in the White neighbourhood of Gage Park, which had a large population of Italian origin. To the south of Gage Park was the neighbourhood of Marquette Park, which had a large population of Lithuanians and other Baltic peoples. Rockwell instructed his men to offer whatever aid they could to the embattled Whites. What began as noisy White counter-protests turned into violent White riots. A new Rockwell innovation, signs bearing the Swastika and the words ‘White Power’ were quickly adopted by the angry Whites as their emblem.

On August 21, Rockwell and his troopers (dressed in civilian clothes) held a mass rally in Marquette Park. Thousands of Whites cheered Rockwell’s call for White unity and White power under the Swastika. Upon the completion of his speech, Rockwell walked through the crowd, which hailed him as a conquering hero showered him with cash donations.

The enemies of the White workers – city hall, the police, the media, the clergy, the Black agitators, and above all the Jews – were shocked by the enthusiastic embrace of Rockwell by the angry Whites. Within days, King and his cohorts had wrapped up a hasty ‘desegregation’ agreement with the politicians and called off all further marches and other provocations. Indeed, King was so embarrassed that he left Chicago, never to return.

On September 10, Rockwell led a ‘White People’s March’ through White neighbourhoods and into the Black ghetto. Some 300 local citizens joined in. More would have participated but were turned back by police cordons. The authorities were once again flabbergasted by grassroots support for Rockwell and the ANP.

Within a year Rockwell was dead, and his vision of building a powerful base of support for the Movement in the areas in which he had had success was never fulfilled. But he had set the precedent for mass action. He had proved that ordinary American Whites will accept National Socialism and NS leadership when the conditions are right.

Rockwell’s final year and the transition to ‘Phase Two’

In the months immediately following the events in Chicago, Rockwell reviewed the state of his party and the progress that it had made. He concluded that it was time to begin to put aside the Phase One activities and concentrate on building a movement with a more serious image and focus. Effective January 1, 1967, he renamed the American Nazi Party as the National Socialist White People’s Party and began to institute other changes. The salutation ‘Sieg Heil!’ was replaced by ‘White Power!’, while ‘Heil Hitler!’ was to be used only within the party and never in public. New literature was written and designed, and older items that had been deliberately scandalous were phased out.

In June, a national leadership conference was held at the party’s national headquarters in Arlington, to brief local leaders from across the country on the movement’s new focus. A new monthly tabloid, entitled White Power: The Newspaper of White Revolution appeared in August, and Rockwell worked feverishly to complete a new book, also entitled White Power.

The specific goal of the new outreach was to recruit and build a base of support among the White middle class, as well as among White service personnel and police officers. Small businessmen were to be specially targeted.

It was at this point that Rockwell was assassinated. His deputy Matt Koehl took over leadership, and with the help of other party old fighters, he attempted to proceed with the changes Rockwell had outlined. How Koehl fared in this endeavour will be discussed in the next instalment of this series. But for now, let us note that in the minds of many people, Rockwell’s reputation, unfortunately, remains linked to the first phase of his program, and not to the next phase, which he was never able to fully implement.

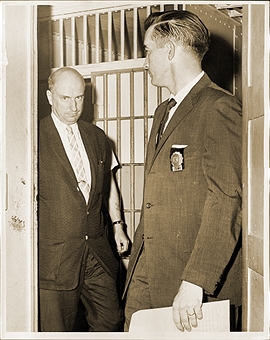

Black Friday: August 25, 1967

On the afternoon of June 28, Rockwell and a supporter were returning to the headquarters, when they found the entranceway blocked by a pile of debris. As the makeshift barricade was being cleared, two shots rang out from the woods to Rockwell’s left. With characteristic courage, Rockwell, who was unarmed, charged his attackers. He gave chase for a quarter mile or so until the two men jumped in a vehicle and drove off. A report was filed with the Arlington County police. A few weeks later, Rockwell applied for a permit to carry a concealed weapon – and was turned down. He privately told his colleagues that from behind one of the men resembled John Patler, a former ANP officer whom he had recently expelled from the party for dereliction of duty and spreading dissension within the ranks.

Two months later, Rockwell was shot dead from an ambush at a local shopping centre. A suspect matching Patler’s description was seen running from the site of the crime, and indeed, Patler was subsequently arrested while waiting at a bus stop some distance away. In 1968, Patler was convicted of second-degree murder, and sentenced to twenty years in prison of which he served seven years. As of this writing, he is still alive and living in New York City.

It was a tragic but foreseeable end to Rockwell’s life. As early as 1962, he had predicted his assassination, writing, ‘I knew that I would not live to see the victory which I would make possible, but I would not die before I had made that victory certain’.

The Carto connection

So far, we have limited the discussion of American National Socialism in the 1960s to Rockwell and his party. As we previously explained, Rockwell’s presence during that period loomed so large that it overshadowed all other groups and efforts to spread the NS message. But no account of the Movement in the Sixties would be complete without mentioning Rockwell’s more mainstream counterpart: Willis Carto. While Rockwell was the face of the hardcore Hitlerian movement, Carto attempted to build support for it in a less-controversial manner.

Like Rockwell, Carto was a World War II veteran who was unhappy with the course that the country had taken in the postwar period. He felt that the government had been infiltrated with communists, and that, further, it was the Jews who were behind communism. Beginning in the mid-1950s, Carto launched a series of publications and business ventures designed to awaken American Whites to the danger that threatened the republic. But unlike Rockwell, Carto resolved to work within the system, and in particular, within the extreme right-wing of the Republican party.

Beginning in 1960, Carto and Rockwell would meet privately to coordinate their efforts. Carto began by publishing an article by Rockwell explaining the ANP and its approach in his publication Right! For this, he was roundly condemned by respectable conservatives who felt that support for Rockwell was beyond the pale of acceptance – whether Rockwell was right or not. Carto brushed off these criticisms by his more-timid colleagues.

Later Carto started a publishing company called Noontide Press (which still exists today). While not openly advocating National Socialism, Noontide produced books and other publications on race and revisionist history that espoused an essentially NS viewpoint. One of these books was a mass-market edition of Imperium: The Politics of Philosophy and History by Francis Parker Yockey. Yockey was a Fascist rather than a National Socialist, but he dedicated his tome to Adolf Hitler, whom he called ‘the Hero of the Second World War’. Carto also lobbied congress, and in other ways spread a message fundamentally the same as Rockwell’s to a mainstream audience.

Other groups

The National States Rights Party founded two years before the ANP was the largest pro-NS group in the country during the Sixties. Although based in the south, it had members and units throughout the US. In 1960, Rockwell was working as hard as he could to stay out of jail and bring in enough money to keep the lights turned on at his headquarters. That same year, the NSRP contested the presidential election, fielding former Arkansas Governor Orville Farbus for president and retired admiral John Crommelin for vice president. The NSRP ticket was on the ballot in five states and won a total of 300,000 votes.

At its height, the NSRP tabloid, The Thunderbolt: The Whiteman’s Viewpoint, had about 25,000 subscribers. Rockwell’s mailing list, in contrast, topped off at about 3,000. And yet, it was Rockwell who had the wider and more lasting impact for the decades.

The debate still rages today whether open advocacy of National Socialism or a slightly modified ‘Americanized’ approach is most effective. Certainly, in day-to-day operations, a concealed approach offers immediate advantages. But the evidence provided by Rockwell’s example suggests that over the long run, an honest, above-board strategy yields the greatest results.

James Madole’s National Renaissance Party was also active throughout the Sixties. However, it became, to a degree, a pale imitation of the ANP. Despite using the thunderbolt instead of the Swastika, and despite using a grey shirt instead of a brown shirt for its activist arm, it never had either the appeal or the success which Rockwell enjoyed.

A splinter of the ANP, called the White Party of America popped up in the middle of the decade. It was led by Karl Allen, former deputy commander of the ANP. The White Party, as it was commonly known, attempted to ape Rockwell’s policies and tactics, but without using the Swastika or referencing Adolf Hitler or National Socialism. It attracted activist types who were put off by Rockwell’s ‘Nazi’ image. In terms of membership, it quickly overtook the ANP. But like the NRP, it never had the impact or influence that Rockwell had.

Rockwell invited Allen and the White Party leadership to the June NSWPP conference mentioned previously. He hoped to merge the two groups or at least ally with them. However, as the conference began, Allen picked a quarrel with Rockwell, and the White Party delegation stormed out. Later, after it was revealed that Allen’s employer was an official of a Jewish dirty-tricks outfit, the White Party disbanded. Some suspect that it was a false flag operation all along, designed to draw manpower and economic support from people who would have otherwise supported Rockwell.

Summing up the Sixties

For American National Socialism, the 1960s was a time for both renewal and experimentation. When the Second World War ended in 1945, it was widely assumed that National Socialism was dead and gone forever, especially in the US, where it had never been that strong, to begin with. But through the courage, genius and Herculean effort of one man, National Socialism was reborn. Although the Rockwell movement did not amount to much in terms of numbers during his lifetime, Rockwell laid the groundwork for the continued existence and growth of his Cause into the future. It was then up to those who took up the mantle of his leadership to determine whether the potential that Rockwell had uncovered would be realized or not.