Editor’s note: With the subtitle ‘Christianity and the Big Lie’, this 12,400-word essay by Laurent Guyénot was published in The Unz Review at Christmas 2020. It will be republished here, excerpted, in five parts.

______ 卐 ______

The People of the Lie

Primo Levi, Italian author of If this is a man (1947)—‘a pillar of Holocaust literature’ according to Wikipedia—, wrote a short fictional story titled Un testamento, consisting of the last recommendation of a member of the guild of the ‘tooth-pullers’ to his son. Its ends with these words:

From all that you have just read you can deduce that lying is a sin for others, and for us a virtue. Lying is one with our job: we should lie by words, by eyes, by smile, by clothing. Not only to deceive patients; as you know, our purpose is higher, and the lie, not the twist of hand, makes our real strength. With the lie, patiently learned and piously exercised, if God helps us we will come to dominate this country and perhaps the world: but this can only be done on the condition of having been able to lie better and longer than our enemies. I will not see that day, but you will see it: it will be a new golden age, when only the last resorts will force us to pluck out teeth again, while it will be enough for us to govern the State and administer public affairs, to lavish the pious lies that we have learned to bring to perfection. If we prove ourselves capable of this, the empire of the tooth-pullers will extend from East to West until the most distant islands, and it will have no end.[1]

There is no literary value in this prose. Its only interest is the question it begs: Who does Levi mean by this society of professional liars, whose trade is passed on from father to son, and whose plan is to conquer the world? Of whom are they the metaphor? And perhaps this other question: What is this ‘testament’ of theirs?

Even if we didn’t know what gang of professional liars Levi belonged to, their ‘God’ would give them away: there is only one god who trained his people to lie and promised them world domination, and that is the god of Israel. ‘Israel,’ remember, is the name Yahweh gave to Jacob, after Jacob lied to his aging father Isaac, by words and by clothing: ‘I am Esau your first-born,’ he said, dressed up in ‘Esau’s best clothes,’ in order to cheat Esau out of his birthright (Genesis 27:15-19). This is, in the literal—and literary—sense, the founding story of Israel. As long as Christians fail to see the malice of it, and its correlation with Jewish behavior, they will continue to play the part of Esau.

What is the biggest Jewish lie in history? Without contest, it is the claim that Jews, of all the nations inhabiting this earth, were once ‘chosen’ by the almighty Creator of the Universe to enlighten and rule over mankind—while all their enemies were cursed by the same Creator. What is truly bewildering is not the enormity of the lie: many individuals may feel chosen by God, and even nations have done so. But only the Jews have managed to convince billions of non-Jews (Christians and Muslims) of their chosenness. How did they do it? ‘Almost by accident,’ wrote Jewish author Marcus Eli Ravage in his must-read 1928 article ‘A real case against the Jews.’ I think the accidental factor was rather minor. [Editor’s note: Remember the article by Marcus Eli Ravage published in The Fair Race: the only article by a Jew to appear in that anthology. Even the Nazis translated it for the Czernowitzer Allgemeine Zeitung.]

The Christians’ theory that, after choosing the Jews, God cursed them for their rejection of Christ doesn’t contradict, but rather validates the Jews’ claim that they are the only ethnic group that God chose, loved exclusively and guided personally through his prophets for thousands of years.

I have argued in ‘The Holy Hook’ that this has given the Jews an ambivalent but decisive spiritual authority over Gentiles. In fact, even the Jews’ ‘cursedness’ that goes with their chosenness in the Christian view has been beneficial to them, because Jewishness cannot survive without hostility to and from the Gentile world; that’s part of its biblical DNA. Jesus saved the Jews in the sense that their hatred of Christianity preserved their identity, which might otherwise have perished without the Temple. According to Jacob Neusner ‘Judaism as we know it was born in the encounter with triumphant Christianity.’[2] Christian Judeophobia had an advantage over Pagan Judeophobia: with Christianity, the Jews were not just hated as atavistically antisocial (i.e., Tacitus’ Histories v, 3-5), but as God’s once chosen people, and their Torah became the world bestseller. [Editor’s note: Compare this with Kevin MacDonald’s ‘adaptive Christianity’: a supposedly good Christianity. In our view, all Christianity was bad for Aryan DNA. Tom Sunic in Homo Americanus blames American Christianity for the crime they committed against the Germans in the last century.]

Chosenness is an unbeatable trump card in the game of nations. If you doubt its power, just ask yourself: would the Jews have gotten Palestine in 1948 without that card? The Holocaust joker alone would not have done it!

As I have become increasingly aware of the resonance between the spiritual and the genetic, as well as of the Jewish war against White identity, I have come to wonder if the revealed notion of Jewish divine preference and predestination has not been a slow debilitating poison injected into our collective soul. Jewish chosenness means a metaphysical superiority that makes us, non-Jews, God’s second choice at best.

Sure, this is not an explicit dogma of Christianity—the Credo doesn’t include ‘I believe that God chose the Jews’—, but only an underlying postulate of Christology. Does that make it less, or more efficient against our rational immune system? It is hard to tell. I believe that Jews have carried their chosenness by the Jealous One as a kind of spooky aura not unlike the mark of Cain that says, ‘Whoever kills Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance’ (Genesis 4:15). (It is appropriate to mention here that Cain is the eponymous ancestor of the Kenites, a Midianite tribe allied to the Israelites during the conquest of Canaan, and that according to the scholarly ‘Kenite hypothesis,’ the Yahwist cult is of Kenite origin.)[3]

How did they do it? How did the Jews manage to smuggle their Big Lie into the exclusive religion of European nations? That is a legitimate and important question, isn’t it? From a purely historical perspective, it remains one of the greatest puzzles; one that secular historians prefer to leave to Church historians, who are comfortable with Constantine hearing voices near the Milvius Bridge. [Editor’s Note: The exception is David Skrbina. See the excerpts we recently published from his book The Jesus Hoax.]

The question is, very simply: How is it that Rome ended up adopting as its spiritual foundation a doctrine and a book claiming that God chose the Jews, at a period of widespread Roman Judeophobia? And how is it possible, that, less than two centuries after turning Jerusalem into a Greek city named Aelia Capitolina, where Jews were forbidden to enter, Rome adopted officially a religion that announced the fall of Rome and a new Jerusalem?

One part of the answer is that uniting the Empire under a common religion has been a major concern of Roman emperors from the very beginning. Before Christianity, it was not a question of eliminating local religions, but of creating a common cult to give a divine legitimacy and a religious bond to the Empire. When they searched for religious inspiration, the Romans generally turned to Egypt. The cults of Osiris (or Serapis, as he came to be called from the third century BC), of his sister-spouse Isis, and of their son Horus (or Harpocrates, Horus the Child) were extremely popular all around the Mediterranean, and provided the Romans with the closest thing to an international religion.

Hadrian (117-138) gave Osiris the features of Antinous, to whom he also dedicated a new city, new games, and a constellation. The origin of Antinous is unclear. The Augustan History tells us that he was the gay lover (eromenos) of Emperor Hadrian, and many historians still reproduce that story, even though the Augustan History has been exposed as the work of an impostor. In all likelihood this story is a Christian propaganda against a competing religion.

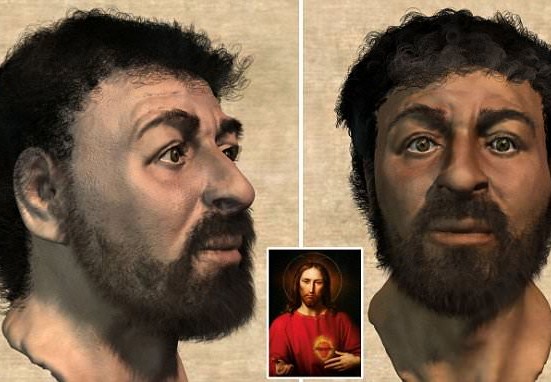

Antinous, whose name is formed of anti, ‘like’, and nous, ‘spirit’, is supposed to have drowned in the Nile on a 24th of October, just like Osiris, and his death was interpreted as a sacrifice. As a divinity, Antinous was assimilated to Osiris, and by extension to Hermes, Dionysos and Bacchus, all divinities of the Afterworld. On a monolithic obelisque found in Rome but built in Antinopolis, Antinous is designated as Osiris Antinous. His cult must therefore be seen as a new expression of the cult of Osiris sponsored by the Empire. Antinous’ face and body, sculpted in thousands of copies, were a self-celebration of the White race that then dominated the world, from Anatolia to Spain, and from Great Britain to Egypt.[4] [Color emphasis by Editor.]

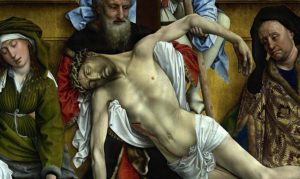

(Left, Antinous as Bacchus, colossal sculpture presumed to have been from Hadrian’s villa in Palestrina.) What a contrast with its competitor, the cult of the Crucified! The question, then, becomes: Why did Christ ultimately supplant Osiris, even absorbing the cult of Isis? How is it that the glorious and self-confident Roman Empire converted to the cult of a Jewish healer tortured and executed by Roman authorities for sedition? This is the Jewish question that few people want to ask. Assuming that Christianity is a human creation—and that’s my premise—, it is obviously a Jewish creation to a large extent. How did Jews manage to create a religion for Gentiles that would ultimately eradicate all other religions in the Empire—beginning with the imperial cult?

(Left, Antinous as Bacchus, colossal sculpture presumed to have been from Hadrian’s villa in Palestrina.) What a contrast with its competitor, the cult of the Crucified! The question, then, becomes: Why did Christ ultimately supplant Osiris, even absorbing the cult of Isis? How is it that the glorious and self-confident Roman Empire converted to the cult of a Jewish healer tortured and executed by Roman authorities for sedition? This is the Jewish question that few people want to ask. Assuming that Christianity is a human creation—and that’s my premise—, it is obviously a Jewish creation to a large extent. How did Jews manage to create a religion for Gentiles that would ultimately eradicate all other religions in the Empire—beginning with the imperial cult?

A full understanding of this question will probably never be reached, but with what we have learned about Jewish ways in the last hundred years, we can try to formulate some reasonable scenario, one that doesn’t involve God talking to emperors, but another talking device—money—as well as political leverage by a Jewish transgenerational network determined to seize control of the religious policy of the Empire. We, today, know that such Jewish transgenerational networks, capable of driving their host Empires or nations to their ruin, do exist. We also know that they are good at fabricating and promoting their Judeocentric macabre religion for the Goyim.

A full understanding of this question will probably never be reached, but with what we have learned about Jewish ways in the last hundred years, we can try to formulate some reasonable scenario, one that doesn’t involve God talking to emperors, but another talking device—money—as well as political leverage by a Jewish transgenerational network determined to seize control of the religious policy of the Empire. We, today, know that such Jewish transgenerational networks, capable of driving their host Empires or nations to their ruin, do exist. We also know that they are good at fabricating and promoting their Judeocentric macabre religion for the Goyim.

____________

[1] Translated from the French: Primo Levi, Lilith et autres nouvelles, Le Livre de Poche, 1989.

[2] Jacob Neusner, Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation, University of Chicago Press, 1987 , pp. ix-xi.

[3] Read Thomas Römer, The Invention of God, Harvard UP, 2015, pp. 137-138, or Hyam Maccoby, The Sacred Executioner, Thames & Hudson, 1982, pp. 13-51. I broached on this topic in my book ‘Our God Is Your God Too, But He Has Chosen Us’: Essays on Jewish Power, AFNIL, 2020, pp. 42-45.

[4] Royston Lambert, Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous, Phoenix Giant, 1984; Christopher Jones, New Heroes in Antiquity, op. cit., pp. 75-83.